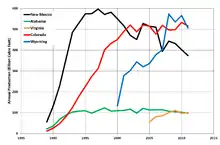

The 2017 production of coalbed methane in the United States was 0.98 trillion cubic feet (TCF), 3.6 percent of all US dry gas production that year. The 2017 production was down from the peak of 1.97 TCF in 2008.[1] Most coalbed methane production came from the Rocky Mountain states of Colorado, Wyoming, and New Mexico.

Coalbed methane reserve estimates vary; however a 1997 estimate from the U.S. Geological Survey predicts more than 700 trillion cubic feet (20 trillion cubic metres) of methane within the US. At a natural gas price of US$6.05 per million Btu (US$5.73/GJ), that volume is worth US$4.37 trillion. At least 100 trillion cubic feet (2.8 trillion cubic metres) of it is economically viable to produce.[2]

The EIA reports 2017 reserves at 11,878 billion cubic feet (BCF) or 11.878 trillion cubic feet,[3] which at a current market price of US $2.97 as of May 14, 2021, are worth approximately $36.2 Billion USD.[4]

History

Coalbed methane grew out of venting methane from coal seams. Some coal beds have long been known to be "gassy," and as a safety measure, boreholes were drilled into the seams from the surface, and the methane allowed to vent before mining. Methane produced in connection with coal mining is usually called "coal mine methane."

Federal support

Coalbed methane received a major push from the US federal government in the late 1970s. Federal price controls were discouraging natural gas drilling by keeping natural gas prices below market levels; at the same time, the government wanted to encourage more gas production. The US Department of Energy funded research into a number of unconventional gas sources, including coalbed methane. Coalbed methane was exempted from federal price controls, and was also given a federal tax credit.

Start of coalbed methane in Alabama

Coalbed methane as a resource apart from coal mining began in the early 1980s in the Black Warrior Basin of northern Alabama.

The American Public Gas Association under a U. S. Department of Energy grant funded a three-well research program in 1980 to produce coalbed methane at Pleasant Grove, Alabama.[5] This program is the first aimed at commercial recovery of gas rather than mine degasification. It is also the first attempt to produce from more than one coal seam in the same wellbore. The coalbed methane wells were drilled on the lawn of the Pleasant Grove court house. The gas was of sufficient quality to be ducted into the kitchens of domestic users after minor processing including odorization as a safety measure.

The Pleasant Grove Field, which was established in July 1980 at a ceremony attended by U.S. Senators, Congressmen and officials of the Administration, was Alabama's first coal degasification field. John Gustavson, a Boulder geologist testified on the results in front of the State Oil and Gas Board of Alabama, who in 1983 established the nation's first comprehensive rules and regulations governing coalbed methane. These rules have served as a model for other states.[6]

Areas of coalbed methane production

- Black Warrior Basin, Alabama

- Powder River Basin, Wyoming

- Raton Basin, Colorado and New Mexico

- San Juan Basin, Colorado and New Mexico

Produced water

The produced water brought to the surface as a byproduct of gas extraction varies greatly in quality from area to area, but may contain undesirably high concentrations of dissolved substances such as salts and total dissolved solids (TDS). Because of the large amounts of water produced, economic water handling is an important factor in the economics of coalbed wells. CBM water from some areas, such as the San Juan Basin of Colorado and New Mexico, is of too poor quality to gain a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit required for discharge to a surface stream, and most be disposed of to a federally licensed Class II disposal well, which injects produced water into saline aquifers below the base of potentially usable water.

In 2008, coalbed methane production resulted in 1.23 billion barrels of produced water, of which 371 million barrels (30 percent), was discharged to surface streams under NPDES permits. Almost all the surface-discharged water was from three areas: the Black Warrior Basin of Alabama, the Powder River Basin of Wyoming, and the Raton Basin of Colorado and New Mexico.[7]

Powder River Basin

Not all coalbed methane produced water is saline or otherwise undesirable. Water from coalbed methane wells in the Powder River Basin of Wyoming, USA, commonly meets federal drinking water standards, and is widely used in the area to water livestock.[8] Its use for irrigation is limited by its relatively high sodium adsorption ratio.

Black Warrior Basin

A large amount of coalbed methane produced water from the Black Warrior Basin has less than 3,000 parts per million (ppm) total dissolved solids (TDS), and is discharged to surface streams under NPDES permits. However, coal beds in other parts of the basin contain greater than 10,000 ppm TDS, and are classed as saline.[9]

Power generation

In 2012, the Aspen Skiing Company built a 3-megawatt methane-to-electricity plant in Somerset, Colorado at Oxbow Carbon's Elk Creek Mine.[10]

Funding methane capture with carbon offsets

The Southern Ute Indian Tribe’s methane capture project has reduced greenhouse gas emissions by the equivalent of about 379,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide between 2009 and 2017.[11] Conventional coal bed methane production wells were not economically feasible in this location due to the low volume of seepage.[12] The project delivers its gas to natural gas pipelines, and generates additional revenue through the sale of carbon offsets.[11][13]

Regulation

As natural gas wells, most of the permitting and regulation of coalbed methane is done by state governments.

Federal regulations apply to the two most common methods of handling CBM produced water. If the water is discharged to a surface stream, it must be done under an NPDES permit or a federally compliant state equivalent. If the water is disposed of by underground injection, it must be to a Class II Disposal Well.

The environmental impacts of CBM development are considered by various governmental bodies during the permitting process and operation, which provide opportunities for public comment and intervention.[14] Operators are required to obtain building permits for roads, pipelines and structures, obtain wastewater (produced water) discharge permits, and prepare Environmental Impact Statements[15] As with other natural resource utilization activities, the application and effectiveness of environmental laws, regulation, and enforcement vary with location. Violations of applicable laws and regulations are addressed through regulatory bodies and criminal and civil judicial proceedings.

See also

References

- ↑ US Energy Information Administration, Coalbed methane production, accessed 9 Oct. 2013.

- ↑ "Coal-Bed Methane: Potential and Concerns" (PDF). US Geological Surveys. usgs.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2003-07-01. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- ↑ "Coalbed Methane Proven Reserves as of 31 December 2017". Energy Information Agency (EIA). 2019-07-31.

- ↑ "NGH20 Quote Overview for Fri, Jan 31st, 2020". Barchart. January 31, 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-01-31. Retrieved 2020-01-31.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-09. Retrieved 2008-02-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Coalbed Methane Association of Alabama". Archived from the original on 2013-10-05. Retrieved 2013-10-09.

- ↑ Technical Development Document for the Coalbed Methane (CBM) Extraction Industry (Report). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). April 2013. EPA-820-R-13-009.

- ↑ "Attachment 5. The Powder River Coal Basin". Evaluation of Impacts to Underground Sources of Drinking Water by Hydraulic Fracturing of Coalbed Methane Reservoirs (Report). EPA. June 2004. EPA-816-R-04-003.

- ↑ Alabama Geological Survey, Water Management Strategies for Improved Coalbed Methane Production in the Black Warrior Basin, undated.

- ↑ Ward, Bob (November 21, 2014). "How Aspen Skiing Co. became a power company". Aspen Times. Archived from the original on 2017-07-08. Retrieved 2019-12-21.

- 1 2 Mullane, Shannon (July 9, 2019). "Outdoors industry taps into Southern Ute methane capture project". Durango Herald. Archived from the original on 2019-07-10. Retrieved 2019-12-21.

- ↑ "Southern Ute Indian Tribe: Natural Methane Capture and Use". Native Energy. 2018. Archived from the original on 2019-12-21. Retrieved 2019-12-21.

- ↑ "Colorado - Native American Methane Capture". Cool Effect. Archived from the original on 2015-10-25. Retrieved 2019-12-21.

- ↑ State of Montana Department of Environment Quality; Coal Bed Methane; Federal, State, and Local Laws, Regulations, and Permits - That May Be Required

- ↑ State of Montana Department of Environment Quality; Final Statewide Oil and Gas EIS and Proposed Amendment of the Powder River and Billings RMPs

External links

- Coalbed Gas - News and Publications - US Geological Survey

- Coalbed Methane Outreach Program - EPA

- Kansas Geological Survey guide to Coalbed Methane