| Montparnasse Cemetery | |

|---|---|

Montparnasse Cemetery viewed from the Tour Montparnasse in 2023 | |

| Details | |

| Established | 1824 |

| Location | |

| Country | France |

| Coordinates | 48°50′17″N 2°19′37″E / 48.83806°N 2.32694°E |

| Type | Non-denominational |

| Owned by | Mairie de Paris |

| Size | 19 hectares (47 acres) |

| No. of graves | 35,000 |

| Website | Montparnasse Cemetery |

| Find a Grave | Montparnasse Cemetery |

Montparnasse Cemetery (French: Cimetière du Montparnasse) is a cemetery in the Montparnasse quarter of Paris, in the city's 14th arrondissement. The cemetery is roughly 47 acres and is the second largest cemetery in Paris.[1] The cemetery has over 35,000 graves and approximately a thousand people are buried here each year.[2]

The cemetery contains 35,000 plots and is the resting place to a variety of individuals including political figures, philosophers, artists, actors, and writers. Additionally, in the cemetery one can find a number of tombs commemorating those who died in the Franco-Prussian war during the siege of Paris (1870–1871) and the Paris Commune (1871).

History

The cemetery was created at the beginning of the 19th century in the southern part of the city. At the same time there were cemeteries outside the city limits: Passy Cemetery to the west, Montmartre Cemetery to the north, and Père Lachaise Cemetery to the east.

In the 16th century the intersecting roads of Vavin and Raspail were dump areas for rubble and stones from nearby quarries. This created an artificial hill and is where "mont" came into the name Montparnasse.[2] Students at the time would congregate on the hill to have fun and participate in open-air dances.[3]

During the French Revolution the land and church were confiscated and the cemetery became property of the government. At this time, anyone who died at the hospital and whose body was not claimed was buried here.

In the 19th century cemeteries were banned in Paris due to health concerns. Several new cemeteries outside the precincts of the capital replaced all the internal Parisian ones: Montmartre Cemetery in the north, Père Lachaise Cemetery in the east, and Montparnasse Cemetery in the south. Montparnasse as well as Père Lachaise and Montmartre replaced the Cimetière des Innocents (those buried here were relocated to the Catacombs).[4] During this time the city of Paris attained the estate and surrounding grounds in order to create a cemetery for the burial of people who lived in the Left Bank of the city. Previously, these inhabitants were buried in the cemetery of Sainte-Catherine and in the village of Vaugirard.

The cemetery at Montparnasse was originally known as Le Cimetière du Sud (Southern Cemetery) and it officially opened 25 July 1824. Since its opening, more than 300,000 people have been buried in Montparnasse.[2]

Moulin de la Charité

In the 17th century the future location of the cemetery consisted of three farms that belonged to the Hôtel-Dieu hospital and an estate of the Brothers of Charity (frères de la Charité). During this time monks built a windmill that later became a Guinguette and the home of the cemetery's caretaker. The mill, which is still standing is the last remnant of the farms.[5]

The cemetery today

The main entrance to the cemetery is north of Boulevard Edgar Quinet near the Edgar Quinet Métro station. The cemetery is divided in two parts by the Rue Émile Richard. The small section is usually referred to as the small cemetery (petit cimetière) and the large section as the large cemetery (grand cimetière). The west of Émile-Richard Street is divided into 21 divisions and to the east of Émile-Richard Street the cemetery is divided into 8 divisions numbered from 22 to 30 (there is no 23rd division).

With 47 acres, Montparnasse is a large green space inside the city limits of Paris. Within the cemetery one can find a variety of trees including linden, Japanese pagoda, thuja, maple, ash, and conifers.[6] Because of the many notable people buried there, it is a popular tourist attraction.

In 2016, the permanent work CAUSSE[7] was installed in the preserved section of the Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris. A prominent French scientist commissioned a tomb from the artist engineer Milène Guermont. This work is a single block of ultra high performance concrete and optical fibers composed of 12 sides to materialize the electron de-multiplier cell invented by the client. This sculpture interacts with the environment: when an individual or a bird passes by, one of its points of light can go out or light up. This work has several peaks that refer to the commissioner's native mountains. The first viewing of the artwork was on November 1, 2016.

Commemorative tombs

Montparnasse Cemetery is the resting place of many of France's intellectual and artistic elite and those who promoted the works of authors and artists. There are graves of foreigners who made France their home as well as monuments to police and firefighters killed in the line of duty.

The cemetery has a number of religious tombs. North of the roundabout is a tomb for priests without family. Rosalie Rendu, member of the society of apostolic life, has an individual tomb in the 14th division that is always well-decorated. Rendu was beatified in 2003 by the Catholic church.

The 5th and 30th divisions were at one time Jewish enclosures and contain many Jewish graves. Adolphe Crémieux, French lawyer and politician, gained citizenship for Jews in French-ruled Algeria in 1870. Alfred Dreyfus, a French Jew, is buried in the south of the cemetery and is famous because of the Dreyfus affair which bears his name. He was unjustly accused and tried for treason, an event that divided France.

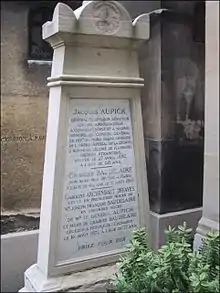

Charles Baudelaire, French poet and author of Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil), is buried in division 6, but there is also a cenotaph to him (between division 26 and 27).

Serge Gainsbourg's grave is also at Montparnasse. Visitors leave a variety of gifts on his gravesite, ranging from flowers and metro tickets to cabbages. Gainsbourg is considered one of the most popular figures in French popular music and was a French singer, songwriter, pianist, film composer, poet, painter, screenwriter, writer, actor and director.[8]

Marguerite Duras' grave is recognizable due to a pot and saucer full of planted pens.[9] Duras moved to Indochina as a child with her parents, but was sent back to France before the beginning of World War II. Novelist, playwright, screenwriter, essayist, and experimental filmmaker, she received a nomination for Best Original Screenplay at the Academy Awards for her script in the film Hiroshima Mon Amour (Hiroshima My Love).

Simone de Beauvoir is buried with Jean-Paul Sartre.

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, the first person to self-proclaim as an anarchist, is also buried here.

Jacques Lisfranc's tomb is in the 13th division. He started his career as a surgeon during the German Campaign of 1813. Lisfranc spread his knowledge about the anatomy of the joints of the foot and used this knowledge to treat many patients.

Multiple generations of a family can be buried in Montparnasse. In the 14th division are three generations of the Deschanel family who all served in the third republic: Émile Deschanel, Paul Deschanel, and Paul-Louis Deschanel. Their bodies rest under the quote, "On n'emporte en mourant que ce que l'on a donné" (We can only take in death what we have given away)

The cemetery does not have a monument dedicated to those who died during World War I.

Location

The boundaries of the cemetery are defined as rue Froidevaux in the south, rue Victor-Schœlcher in the east, boulevard Edgar-Quinet in the north, and rue de la Gaîté in the west. However, the main entrance to the cemetery is on Boulevard Edgar Quinet which leads to the large cemetery. There are smaller entrances to both the large and small cemeteries on Rue Émile Richard (near the junction with both Boulevard Raspail and Boulevard Edgar Quinet).

Gallery

Porfirio Díaz grave.

Porfirio Díaz grave. Tomb of Charles Baudelaire

Tomb of Charles Baudelaire The Charles Baudelaire Cenotaph.

The Charles Baudelaire Cenotaph. Julio Cortázar's grave.

Julio Cortázar's grave. Grave of Urbain Le Verrier

Grave of Urbain Le Verrier Grave of François Pouqueville

Grave of François Pouqueville Grave of Edgar Quinet

Grave of Edgar Quinet Grave of Jean Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir

Grave of Jean Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir Grave of Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir

Grave of Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir Tomb of Shapour Bakhtiar

Tomb of Shapour Bakhtiar Grave of Pierre Restany and Jos De Cock

Grave of Pierre Restany and Jos De Cock.jpg.webp) Aerial view of Cemetery

Aerial view of Cemetery

See also

References

- ↑ Paris. Michelin. 2019. p. 57. ISBN 978-2067237322.

- 1 2 3 Barozzi, Jacques (2012). Secrets Des Cimetières de Paris. France: massin. p. 68. ISBN 978-2707207630.

- ↑ Paris Le Guide Vert. Michelin. 2013. p. 420. ISBN 978-2067186200.

- ↑ Meier, Allison (2019). "Montparnasse Cemetery".

- ↑ Paris, Office du Tourisme et des Congrès de. "Moulin de la Charité – Montparnasse – Office de tourisme Paris". www.parisinfo.com (in French). Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ↑ Malher, Frédéric. "Oiseaux nicheurs de Paris, un atlas urbain" – via Par les équipes de la LPO Ile-de-France aux éditions Delachaux et Niestlé.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "CAUSSE (2016)". Milène GUERMONT.

- ↑ "Obituary". Variety. 11 March 1991.

- 1 2

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/monceau/43768497471

- https://4.bp.blogspot.com/-aJQjj38IpGg/W7w2Uu_dlLI/AAAAAAAAIJw/kI5p6wmVUOge8SHhsY5iKpBRmzK48WKIQCLcBGAs/s1600/IMG_3795.jpg

- https://www.landrucimetieres.fr/spip/spip.php?article861

- https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo/marguerite-duras-grave-montparnasse-cemetery.html