Chutia Kingdom | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

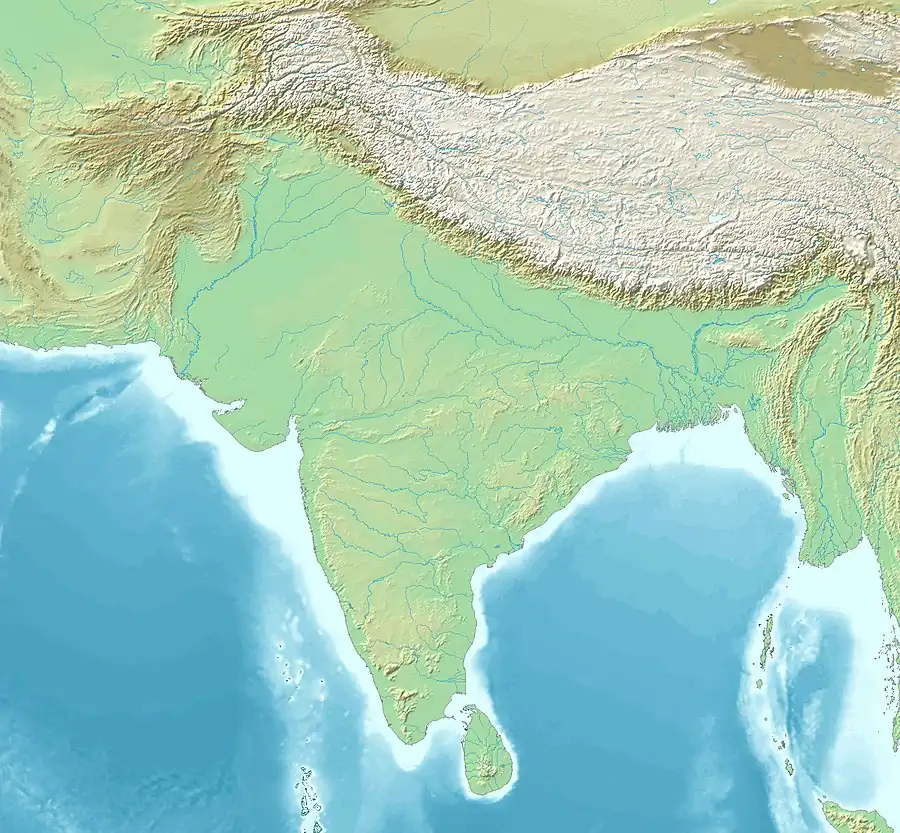

◁ ▷ Chutia kingdom (Tiwra) in early 16th century[1] | |||||||||

| Capital | Sadiya | ||||||||

| Common languages | Assamese language Deori language | ||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism Tribal religion | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||

• Unknown–1524 | Dhirnarayana (last) | ||||||||

| Historical era | Medieval Assam | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | India | ||||||||

| Rulers of Chutia kingdom | |

|---|---|

| Part of History of Assam | |

| Known rulers of the Chutia kingdom | |

| Nandisvara | late 14th century |

| Satyanarayana | late 14th century |

| Lakshminarayana | early 15th century |

| Durlabhnarayana | early 15th century |

| Pratyakshanarayana | mid 15th century |

| Yasanarayana | mid 15th century |

| Purandarnarayana | late 15th century |

| Dhirnarayana | unknown - 1524 |

| Chutia monarchy data | |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Assam |

|---|

|

| Categories |

|

The Chutia Kingdom[8] (also Sadiya[9]) was a late medieval state that developed around Sadiya in present Assam and adjoining areas in Arunachal Pradesh.[10] It extended over almost the entire region of present districts of Lakhimpur, Dhemaji, Tinsukia, and some parts of Dibrugarh in Assam,[11] as well as the plains and foothills[12] of Arunachal Pradesh.[13] The kingdom fell in 1523–1524 to the Ahom Kingdom after a series of conflicts and the capital area ruled by the Chutia rulers became the administrative domain of the office of Sadia Khowa Gohain of the Ahom kingdom.[14]

The Chutia kingdom came into prominence in the second half of the 14th century,[15] and it was one among several rudimentary states (Ahom, Dimasa, Koch, Jaintia etc.) that emerged from tribal political formations in the region, between the 13th and the 16th century.[16] Among these, the Chutia state was the most advanced,[17][18] with its rural industries,[19] trade,[20] surplus economy and advanced Sanskritisation.[21][22] It is not exactly known as to the system of agriculture adopted by the Chutias,[23] but it is believed that they were settled cultivators.[24] After the Ahoms annexed the kingdom in 1523, the Chutia state was absorbed into the Ahom state — the nobility and the professional classes were given important positions in the Ahom officialdom[25][26] and the land was resettled for wet rice cultivation.[27]

Foundation and Polity

Though there is no doubt on the Chutia polity, the origins of this kingdom are obscure.[28] It is generally held that the Chutias established a state around Sadiya and contiguous areas[10]—though it is believed that the kingdom was established in the 13th century before the advent of the Ahoms in 1228,[29] and Buranjis, the Ahom chronicles, indicate the presence of a Chutia state[30] the evidence is scarce that it was of any significance before the second half of the 14th century.[31]

The earliest Chutia king in the epigraphic records is Nandin or Nandisvara, from the latter half of the 14th century,[32] mentioned in a grant by his son Satyanarayana who nevertheless draws his royal lineage from Asuras in his mother's side who were "enemies of the gods".[33] The mention of Satyanarayana as having the shape of his maternal uncle (which is also an indirect reference to the same Asura/Daitya lineage)[34] may also constitute evidence of matrilineality of the Chutia ruling family, or that their system was not exclusively patrilineal.[35] On the other hand, a later king Durlabhnarayana mentions that his grandfather Ratnanarayana (identified with Satyanarayana) was the king of Kamatapura[36] which might indicate that the eastern region of Sadhaya was politically connected to the western region of Kamata.[37]

In these early inscriptions, the kings are said to be seated in Sadhyapuri, identified with the present-day Sadiya;[38] which is why the kingdom is also called Sadiya. The Buranjis written in the Ahom language called the kingdom Tiora (literal meaning: Burha Tai/Elder Tai) whereas those written in the Assamese language called it Chutia.[8]

Brahmanical influence in the form of Vaishnavism reached the Chutia polity in the eastern extremity of present-day Assam during the late fourteenth century.[39][40] Vaishnava Brahmins created lineages for the rulers with references to Krishna legends but placed them lower in the Brahminical social hierarchy because of their autochthonous origins.[41] Though asura lineage of the Chutia rulers have similarities with the Narakasura lineage created for the three Kamarupa dynasties, the precise historical connection is not clear.[42] Although a majority of the Brahmin donees of the royal grants were Vaishnavas,[43] the rulers patronized the non-brahmanised Dikkaravasini[44] (also Tamresvari or Kechai-khati), which was either a powerful tribal deity, or a form of the Buddhist deity Tara adopted for tribal worship.[45] This deity, noticed in the 10th century Kalika Purana well before the establishment of the Chutia kingdom, continued to be presided by a Deori priesthood well into the Ahom rule and outside Brahminical influence.[46]

The royal family traced its descent from the line of Viyutsva.[47]

Spurious accounts

Unfortunately, there are many manuscript accounts of the origin and lineage that do not agree with each other or with the epigraphic records and therefore have no historical moorings.[48][49] One such source is Chutiyar Rajar Vamsavali, first published in Orunodoi in 1850 and reprinted in Deodhai Asam Buranji.[50] Historians consider this document to have been composed in the early 19th century—to legitimize the Matak rajya around 1805—or after the end of Ahom rule in 1826.[51] This document relates the legend of Birpal. Yet another Assamese document, retrieved by Ney Elias from Burmese sources, relates an alternative legend of Asambhinna.[52] These different legends suggest that the genealogical claims of the Chutias have changed over time and that these are efforts to construct (and reconstruct) the past.[53]

Rulers

Only a few recently compiled Buranjis provide the history of the Chutia kingdom;[54] though some sections of these compilations are old, the sections that contain the list of Chutiya rulers cannot be traced to earlier than 19th century[55] and scholars have shown great disdain for these accounts and legends.[56]

Neog (1977) compiled a list of rulers from epigraphic records based crucially on identifying the donor-ruler named Dharmanarayan, mentioned as the son of Satyanarayana in the Bormurtiya grant[57] with the Dharmanarayan, the father of the donor-ruler Durlabhnarayana of the Chepakhowa grant.[58] This effectively results in identifying Satyanarayana with Ratnanarayana.[59]

| Name | Other names | Reign Period | Reign in Progress |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nandi | Nandisara or Nandisvara | late 14th century[61] | |

| Satyanarayana | Ratnanarayana | late 14th century[61] | 1392[62] |

| Lakshminarayana | Dharmanarayana or Mukta-dharmanaryana[63] | early 15th century | 1392;[64] 1401;[65] 1442[66] |

| Durlabhnarayana | early 15th century | 1428[67] | |

| Pratyaksanarayana[68] | |||

| Yasanarayana[68] |

A late discovery of an inscription, published in a 2002 souvenir of the All Assam Chutiya Sanmilan[69] seems to genealogically connect the last historically known king, Dhirnarayan with Neog's list above.

| Name | Other names | Reign Period | Reign in progress |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yasamanarayana[70] | |||

| Purandarnarayana | late 15th century | ||

| Dhirnarayana | early 16th century | 1522[71] |

Though it is accepted that the rule of the Chutia rulers ended in 1523,[72] different sources give different accounts.[73] The extant Ahom Buranji and the Deodhai Asam Buranji mention that in the final battles and the aftermath both the king (Dhirnarayan) and the heir-apparent (Sadhaknarayan) were killed;[74] whereas Ahom Buranji-Harakanta Barua mentions that the remnant of the royal family was deported to Pakariguri, Nagaon—a fact that is disputed by scholars.[75][76]

Domain

The extent of the power of the kings of the Chutia kingdom is not known in detail.[77] Nevertheless, it is estimated by most modern scholarship that Chutias held the areas on the north bank of Brahmaputra from Parshuram Kund (present-day Arunachal Pradesh) in the east and included the present districts of Lakhimpur, Dhemaji, Tinsukia and some parts of Dibrugarh in Assam.[11][78] Between 1228 and 1253 when Sukaphaa, the founder of the Ahom kingdom, was searching for a place to settle in Upper Assam, he and his followers did not encounter any resistance from the Chutia state,[79] implying that the Chutia state must have been of little significance till at least the mid 14th century,[80] when the Ahom chronicles mention them for the first time. However, it is also known that the Ahoms themselves were a people with a precariously small territory and population, which may indicate this absence of serious interaction with the old settled people of the neighborhood until the 14th century.[81] At its largest extent, the Chutia influence might have extended up to Viswanath in the present Darrang district of Assam,[50][82][83] though the main control was confined to the river valleys of Subansiri, Brahmaputra, Lohit and Dihing and hardly extended to the hills even at its zenith.[84]

- Ruins of the Chutia kingdom near Dibang Valley of Arunachal Pradesh

View of the platform of the central building.

View of the platform of the central building. View of a ruined building

View of a ruined building

Early contacts and downfall

With Ahoms and Bhuyans (14th century)

The earliest mention of a Chutia king is found in the Buranjis that describe a friendly contact during the reign of Sutuphaa (1369–1379),[85] in which the Ahom king was killed. To avenge the death the next Ahom ruler Tyaokhamti (1380–1387) led an expedition against the Chutiya kingdom but returned with no success.[86] During the same era (late 14th century) Gadadhara, the younger brother of Rajadhara and a descendent of Candivara in order to expand his influence collected a large army at Borduwa and attacked the Chutiyas and Khamtis but was held captive, he was later set free and had to settle at Makhibaha (in present-day Nalbari district).[87][88]

Chutia-Ahom conflicts (1512–1523)

Suhungmung, the Ahom king, followed an expansionist policy and annexed Habung and Panbari in either 1510 or 1512, which, according to Swarnalata Baruah, was ruled by Bhuyans[89] while according to Amalendu Guha, it was a Chutia dependency.[90] In 1513 a border conflict triggered the Chutia king Dhirnarayan to advance to Dikhowmukh and build a stockade of banana trees (Posola-garh).[91][92] This fort was attacked by a force led by the Ahom king himself leading to a rout of the Chutia soldiers. This was followed by the Ahoms erecting a fort at Mungkhrang, which fell within the Chutia territory.[92]

In 1520 the Chutias attacked the Ahom fort Mungkhrang twice and in the second killed the commander and occupied it, but the Ahoms, led by Phrasengmung and King-lung attacked it by land and water and recovered it soon and erected an offensive fort on the banks of the Dibru River. In 1523 the Chutia king attacked the fort at Dibru but was routed. The Ahom king with the assistance of the Bhuyans[93] hotly pursued the retreating Chutia king who sued for peace. The peace overtures failed and the king finally fell to Ahom forces, bringing an end to the Chutia kingdom.[94][95] Though some late spurious manuscripts mention the fallen king as Nitipal (or Chandranarayan) the extant records from the Buranjis such as the Ahom Buranji and the Deodhai Ahom Buranji do not mention him; rather they mention that the king (Dhirnarayan) and the prince (Sadhaknarayan) were killed.[96] As a reward for the assistance, the Ahom king settled this Bhuyans in Kalabari, Gohpur, Kalangpur and Narayanpur as tributary feudal lords.[97]

Legacy

The Ahom kingdom took complete possession of the royal insignia and other assets of the erstwhile kingdom.[98][99] The rest of the royal family was dispersed, the nobles were disbanded and the territory was placed under the newly created office of the Sadiakhowa Gohain.[100] Besides the material assets and territories, the Ahoms also took possession of the people according to their professions. Many of Brahmans, Kayasthas, Kalitas, and Daivajnas (the caste Hindus), as well as the artisans such as bell-metal workers, goldsmiths, blacksmiths, and others, were moved to the Ahom capital and this movement greatly increased the admixture of the Chutia and Ahom populations.[99] A sizeable section of the population was also displaced from their former lands and dispersed in other parts of Upper Assam.[101][102]

After annexing the Chutia kingdom, offices of the Ahom kingdom, Thao-mung Mung-teu(Bhatialia Gohain) with headquarters at Habung (Lakhimpur), Thao-mung Ban-lung(Banlungia Gohain) at Banlung (Dhemaji), Thao-mung Mung-klang(Dihingia gohain) at Dihing (Dibrugarh, Majuli and northern Sibsagar), Chaolung Shulung at Tiphao (northern Dibrugarh) were created to administer the newly acquired regions.[103]

Firearms

The Chutias may have been the first people in Assam to use firearms. When the Ahoms annexed Sadiya, they recovered hand-cannons called Hiloi[104] as well as large cannons called Bor-top, Mithahulang being one of them.[105][106][107] As per Maniram Dewan, the Ahom king Suhungmung received around three thousand blacksmiths after defeating the Chutias. These people were settled in the Bosa (Doyang) and Ujoni regions and asked to build iron implements like knives, daggers, swords as well as guns and cannons.[108] The Chutias were defeated in 1523 which might point out that the Ahoms learned the use of gunpowder from the Chutias[109] and most of the Hiloi-Khanikars (gunmakers) belonged to the Chutia community.[110]

See also

References

- ↑ "Ramirez, Philippe,People of the Margins:Chapter 1,p.4". Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ↑ Barua, Sarbeswar,Purvottar Prabandha, p. 212

- ↑ Kalita, Bharat Chandra, Military activities in Medieval Assam,p.23

- ↑ Saikia, Yasmin,In the Meadows of Gold, p. 190.

- ↑ Dutta 1985, p. 30.

- ↑ Saikia, Yasmin, In the Meadows of Gold, p. 190.

- ↑ Barua, Swarnalata, Chutia Jatir Buranji, p.139.

- 1 2 "In the past, there was a kingdom in Upper Assam that the Ahom chronicles called Tiora and the Assamese chronicles called Chutiya." (Jaquesson 2017:100)

- ↑ "Their kingdom called Sadiya..." (Gogoi 2002:20)

- 1 2 "(T)he Chutiyas seem to have assumed political power in Sadiya and contiguous areas falling within modern Arunachal Pradesh." (Shin 2020:51)

- 1 2 "Their kingdom called Sadiya extended in the north over the entire region from the Sisi in the west to the Brahmaputra in the east. The hills and the river Buri Dihing formed its northern and southern boundaries respectively. Thus the Chutiya territory extended over almost the entire region of present districts of Lakhimpur, Dhemaji, Tinsukia, and some parts of Dibrugarh." (Gogoi 2002:20–21)

- ↑ (Shin 2020:57) "The ruins of two forts in Lohit district of Arunachal Pradesh is said to be the remains of Bhīṣmaka's city, viz. Bhismaknagar (sk. Bhīṣmakanagara): one ruin about 16 miles northwest of Sadiya at the foot of the hills between the rivers Dikrang and Dibang is known as the fort of Bhīṣmaka, and the other about 24 miles north of Sadiya between the gorges of those two rivers is believed to be the fort of Śiśupāla. Based on an inscribed brick with the name of Śrīśrī-Lakṣmīnārāyaṇa, discovered from the ruins of the forts in Bhismaknagar, it is assumed that Chutiya king Lakṣmīnārāyaṇa of the early fifteenth century had his capital in the area. The paleographical analysis of the inscription supports this dating."

- ↑ "In the main, however, their territory was confined to the river valleys of the Suvansiri, Brahmaputra, Lohit, and the Dihing and hardly extended to the hills at its zenith."(Nath 2013:27)

- ↑ "The Chutiya power lasted until 1523 when the Ahom king Suhungmung, alias Dihingia Rāja (1497–1539), conquered their kingdom and annexed it to his sphere of influence. A new officer of Ahom state, known as Sadiya Khowa Gohain, was appointed to administer the area ruled by the Chutiyas." (Shin 2020:52)

- ↑ "It is more likely that if there was a Chutiya state at this time, it was of little significance until the second half of the fourteenth century." (Shin 2020:52)

- ↑ "The period from the 13th to the 16th century saw the emergence and development of a large number of tribal political formations in northeast India. The Chutiya, the Tai-Ahom, the Koch, the Dimasa (Kachari), the Tripuri, the Meithei (Manipuri), the Khasi (Khyriem), and the Pamar (Jaintia)—all these tribes crystallised into rudimentary state formations by the 15th century." (Guha 1983:5)

- ↑ "The most developed of the tribes in the 15th century were the Chutiya." (Guha 1983:5)

- ↑ "Indeed it appears that of all the tribes of the Brahmaputra valley, the Chutiyas were the most advanced and had a well-developed civilization."(Datta 1985:29)

- ↑ "The growth of a number of professions among the people of this kingdom like tanti (weaver), kahar (bell-metal worker), sonari (goldsmith) ... indicates the growth of some rural industries among the Chutiyas." (Gogoi 2002:22)

- ↑ "(T)he Chutias, who held power by regulating the easterly trade and migration of people to and from Tibet, Southern China, and Assam." (Saikia 2004:8)

- ↑ "(T)he Chutiyas were one of the earliest tribes to be Hinduised and to form a state, may point to their surplus economy." (Gogoi 2002:21–22)

- ↑ (At the time of annexation by the Ahoms) caste system had become prevalent in (the Chutiya) society." (Gogoi 2002:21)

- ↑ "It is not definitely known as to the system of agriculture adopted by them." (Gogoi 2002:22)

- ↑ "It must be noted, however, that the word 'khā' of Tai-Ahom language, which is usually prefixed to names of non-Ahom people practicing shifting cultivation, does not appear for the Chutiyas, probably because they were neither stateless nor were they solely shifting cultivators in the early phase of Ahom rule. There seems no serious interaction between the Ahoms and old settled people of the neighborhood including the Chutiyas until the fourteenth century." (Shin 2020:51)

- ↑ (Baruah 1986:186)

- ↑ "The Ahoms accepted many Chutiyas to their fold and offered them responsible offices in the administration"(Dutta 1985:30)

- ↑ "[T]he Chutiya kingdom consisted of a vast plan level and fertile territory which provided for the Ahoms possibility of easy extension of wet rice culture in the region." (Gogoi 2002:22)

- ↑ "The origin of the Chutiya state is obscure."(Buragohain 2013:120)

- ↑ "(T)he Chutiyas formed a state earlier than the Ahoms in the thirteenth century." (Nath 2013:25)

- ↑ (Guha 1983:fn.16) "The prefix Kha does not appear in the Tai words for the Dimasa and the Chutiya, probably because they were neither stateless, nor-were they solely shifting cultivators."

- ↑ "The first confrontation between the Ahoms and the Chutiyas as a political power is mentioned in some chronicles such as the Deodhai Asam Buranji only during the reign of Ahom king Sutupha (1369–76), about a hundred years after the death of Sukapha. It is more likely that if there was a Chutiya state at this time, it was of little significance until the second half of the fourteenth century...There seems no serious interaction between the Ahoms and old settled people of the neighborhood including the Chutiyas until the fourteenth century as both the Ahom territory and its population remained precariously small."(Shin 2020:52)

- ↑ "On the basis of these records, Neog reconstructed a line of kings ruling this region as follows: Nandin (or Nandīśvara), Satyanārāyaṇa (or Ratnanārāyaṇa), Lakṣmīnārāyaṇa, Durlabhanārāyaṇa, Dharmanārāyaṇa, Pratyakṣanārāyaṇa and Yaśanārāyaṇa (or Yamanārāyaṇa). Furthermore, it is fairly certain from the dates available in the inscriptions that Nandin and Satyanārāyaṇa ruled Sadhayāpurī in the latter half of the fourteenth century." (Shin 2020:52)

- ↑ "According to the Dhenukhana copper plate inscription of Satyanārāyaṇa and Pratyakṣanārāyaṇa, dated 1314 Śaka (1392 AD), king Nandin (or Nandi), a great hero of many virtues, was the lord of Sadhayāpurī (sadhayāpurīśa), and Daivakī, Nandin's wife, was continuously accomplishing good deeds. Auspicious Satyanārāyaṇa had his origin in Daivakī's womb, 'forming part of the lineage of the enemy of the gods' (suraripu-vaṃśāṃśa-bhūto), making the uplift of the burden of the earth. Neog interprets 'the lineage of the enemy of the gods' as the asura dynasty"(Shin 2020:53)

- ↑ "The reason for his asura lineage is not explicitly explained in the inscription, but the two statements that his mother is 'Daivakī' and he has 'the shape of a maternal uncle (who was) given the name of Daitya'(daityanāmāttamāmāmatiḥ) can be seen as an indirect reference to his lineage." (Shin 2020:53)

- ↑ "The epigraphic record of Satyanārāyaṇa, whose lineage is named in reference to his maternal uncle, is therefore significant. It may constitute evidence of matrilineality of the Sadiya-based Chutiya ruling family, or that their system was not exclusively patrilineal."(Shin 2020:54)

- ↑ "Ratnanãrãyana is called the king of Kamatãpura and his grandson Durlabhanãrãyana is described as giving lands under the administration of the Governor of Häbunga province." (Neog 1977:818)

- ↑ "The eastern region, whether it is called Sadhaya or Svadhaya as in the plates or Sadhiya or Sadiya as in Assamese chronicles and the western region of Kamatapura seems to be politically connected and the same Satyanarayana/Ratnanarayana might have held sway over both regions"(Neog 1977:818)

- ↑ "Furthermore, it is fairly certain from the dates available in the inscriptions that Nandin and Satyanārāyaṇa ruled Sadhayāpurī in the latter half of the fourteenth century, while Lakṣmīnārāyaṇa belonged to the beginning, and Dharmanārāyaṇa to the middle of the fifteenth century. It is also nearly clear that Sadhayāpurī (or Svadhayāpurī) mentioned in the inscriptions is the same as Sadhiyā or Sadiya of later times." (Shin 2020:52)

- ↑ "These records suggest the penetration of Vaiṣṇava tradition in the eastern extremity of present Assam between the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries"(Shin 2020:55)

- ↑ "They had definitely come under Brahminical influence during the late fourteenth and early fifteenth century, as is borne out by the evidence of their landgrants in favour of Brahmana beneficiaries"(Momin 2006:47)

- ↑ "Vaiṣṇava brahmins seemed to play an important role in the making of both the royal lineages defined as 'demonic'; and ... this demonic maternal ancestry was the way to accommodate the local ruling families in the Brahmanical social hierarchy, but only in a lower position." (Shin 2020:55)

- ↑ "Though it is not clear whether the asura lineage of Chutiya ruling family had a historical connection with this earlier tradition of Kāmarūpa, there are some common points between the two genealogical claims..." (Shin 2020:54–55)

- ↑ "Most names of brahmin donees have Vaiṣṇava affiliation." (Shin 2020:55)

- ↑ " The Pãyã-Tãmresvari (Dikkaravãsiní) temple inscription announces that King Dharmanãrãyana raised in 1364 Šaka a wall (prãkãra) around the temple of Dikkaravãsiní, popularly known as Tãmresvari." (Neog 1977:817)

- ↑ (Gogoi 2011:235–236)

- ↑ 'According to E.A. Gait, "The religion of the Chutiyas was a curious one. They worshipped various forms of Kali with the aid not of the Brahmanas but of their own tribal priests or Deoris. The favorite form in which they worshipped this deity was that of Kesai-khati 'the eater of raw flesh' to whom human sacrifices were offered. After their subjugation by the Ahoms, the Deoris were permitted to continue their ghastly rites; but they were usually given for this purpose, criminals who have been sentenced to capital punishment..."' (Gogoi 2011:236)

- ↑ (Baruah 2007:42) The 1392 Bormurtia grant of Satyanarayan mentions Viyutsva-kula while the 1522 Dhakuakhana grant of Dhirnarayan mentions Viyutsva-banshada

- ↑ "There are various accounts and succession lists of the rulers of the Chutiyãs (I do not call them Chutiyã kings precisely because in these accounts they are not described as Chutiyãs except the last one of them) with dates also assigned to their reign, but these accounts are too much at variance with one another to deserve serious consideration as being of proper historical value." (Neog 1977:814)

- ↑ "The legends relating to the origin of the Chutiyas is full of absurdities without any historical moorings." (Buragohain 2013:120)

- 1 2 (Nath 2013:27)

- ↑ "[T]his so-called ancient chronicle might have been a later work of some members of the Chutiya aristocracy, as is possibly an attempt to legitimize the claims of the Chutiyas over a part of Assam during the establishment of the Matak kingdom at the beginning of the 19th century (1805) or after the Ahom power was abolished." (Nath 2013:27)

- ↑ (Nath 2013:29–30)

- ↑ "What can be said for sure is that the genealogical claims of the Chutiyas changed in the course of time, and the related legend reflects a difference in the way the Chutiyas construct (or reconstruct) their past." (Shin 2020:58–59)

- ↑ "Only a few chronicles of comparatively recent date, including the Deodhai Asam Buranji, Ahom Buranji, Satsari Asam Buranji, Purani Asam Buranji and the Asam Buranji obtained from the family of Sukumar Mahanta, preserve only a small part of their history." (Shin 2020:52)

- ↑ "The following list of rulers of the Chutiyãs is given in one of the two short chronicles of them incorporated by Dr. S. K. Bhuyan in his Deodhäi Asam Burañji from an old manuscript published by William Robinson in the Baptist journal, Orunodoi, December 1850. It very nearly corroborates a similar list in the vamsävali obtained by Kellner from Amrtanãrãyana of a Chutiyã princely family. Even Kellner considered this chronology apocryphal (Brown, op. cit., p. 83 ). It is not yet known for certain when at all such lists were prepared, but at the moment it is not possible to ascribe them to a date earlier than the 19th century. The dates given in the lists do not thus have historical moorings." (Neog 1977:817–818)

- ↑ " It is not known for sure when the story of Birpal was made nor when the list of kings was prepared; but at the moment, it is not possible for a scholar like Neog to ascribe them a date earlier than the nineteenth century. Scholars, therefore, questioned the accuracy of the historical information in these accounts and showed great disdain for the related legends.(Shin 2020:52)

- ↑ (Neog 1977:816)

- ↑ "An attempt might perhaps be made to correlate all these finds into the reconstruction of a line of kings ruling in this region. If we consider Dharmanãrãyana of the epigraphs [Bormurtiya], [Chepakhowa] and [Paya-Tamreshvari] as the same..." (Neog 1977:817)

- ↑ "We seek to identify Satyanãrãyana of Sadhayãpuri of Dhenukhanã, Ghilãmarã, and Barmurtiyã-bil plates with Ratnanãrãyana of Kamatãpura of the Sadiyã-Chepã-khowã plate, as Dharmanãrãyana is described as Satyanäräyana's son in the Barmurtiyã-bil plate and as Ratnanârâyana's son in the Sadiyã-Chepãkhowâ plate, and, as already pointed out, more than one name seems to have been assumed by the kings of this region. (Neog 1977:818)

- ↑ (Neog 1977:817)

- 1 2 "It is, however, fairly certain from the dates available in the epigraphs that King Nandisvara and Satyanarayana ruled in Sadhayapuri in the last half of the 14th century A.D." (Neog 1977:820)

- ↑ "Dhenukhanã copperplate grant of King Satyanãrãyana, son of Nandi, Nandisara or Nandivara, of Sadhayâpurï or Svadhayãpuri, dated 1392." (Neog 1977:813)

- ↑ "Dr. D. C. Sircar seeks to read the name of the king as 'Muktãdharmanãrãyana' which may really have been 'yuvã-Dharmanãrãyana' contrasting well with the reference to the bṛddharãja' in the first line of the inscription." (Neog 1977:813)

- ↑ "Barmurtiyã-bil copperplate inscription of King Dharmanãrãyana, son of Satyanãrãyana, dated 1392" (Neog 1977:813)

- ↑ "Ghilãmarã copperplate grant of King Laksmlnãrãyana, son of Satyanãrãyana, dated 1401." (Neog 1977:813)

- ↑ "Pãyã-Tãmresvari (Dikkaravãsini) temple wall inscription of King Dharmanãrãyana, son-regent of Brddharãja (Old King), dated 1364 Šaka/1442 AD" (Neog 1977:813)

- ↑ "The Sadiyã-Chepãkhowã copperplate grant of King (Durlabha-)nãrãyana, son of Dharmanãrãyana and grandson of Ratnanãrãyana originally of Kamatãpura, dated 1350 Šaka/1428 AD." (Neog 1977:813)

- 1 2 "In the Dhenukhanã plate two later kings seem to have added postscripts to the original inscription of 1314 Šaka. They are Pratyaksanãrãyana and Yasanãrãyana or Yamanãrãyana. No dates are associated with them." (Neog 1977:819)

- ↑ (Nath 2013:43ff)

- ↑ (Baruah 2007:124) "The plate discovered in 2001 identifies Yamkadnarayana or Yasamanarayana as the grandfather(pitamah) of Dhirnarayana. It is possible that this king was the same as Yasanarayana or Yamanarayana of the Dhenukhana plate."

- ↑ (Baruah 2007:590–591)

- ↑ "The most developed of the tribes in the 15th century were the Chutiyas. Their kingdom was annexed and absorbed by the Tai-Ahoms by 1523." (Guha 1983:5)

- ↑ "Regarding the fate of the Chutia prince Sadhaknarayan and the identity of the Chutia king killed by the Ahoms in 1523-24, opinions differ." (Baruah 1986:229ff)

- ↑ "The Ahom Buranji and the Deodhai Assam Buranji do not mention the name of Nitipal alias Chandranarayan. These sources ascribe the event to the reign of Dhirnarayan and state that in the final clash both the Chutia king (Dhirnarayan) and the prince (Sadhaknarayan) were killed." (Baruah 1986:229f)

- ↑ "Suhunmung then deported the Chutiya nobles and the prince Sadhaknarayan to his kingdom and established the later at Darrang with grants of land and labourers."(Gogoi 2002:21)

- ↑ "But as L. Devi points out, if at all the Ahoms spared the life of the Chutiya prince then the latter might have been established not at Nowgong, which was yet to be conquered by the Ahoms but on the north bank near about Mangaldai." (Baruah 1986:229ff)

- ↑ "(T)he geographical extent of these rulers' power is not yet known in detail..." (Shin 2020:52)

- ↑ Acharya.N.N., The History of Medieval Assam, 1966,p.232

- ↑ "The Assamese chronicles while recording the route of Sukapha across the Patkai hills till he reached Charaideo in the southeastern corner of the present Sibsagar district through the courses of the rivers Dihing, Brahmaputra and Dikhow do not mention a Chutiya state that offered any kind of resistance to the advancing forces of Sukapha." (Nath 2013:26)

- ↑ "This shows that if there was any Chutiya state it was of little significance till at least mid 14th century." (Nath 2013:26)

- ↑ "It must be noted, however, that the word 'khā' of Tai-Ahom language, which is usually prefixed to names of non-Ahom people practicing shifting cultivation, does not appear for the Chutiyas, probably because they were neither stateless nor were they solely shifting cultivators in the early phase of Ahom rule. There seems no serious interaction between the Ahoms and old settled people of the neighborhood including the Chutiyas until the fourteenth century as both the Ahom territory and its population remained precariously small."(Shin 2020:52)

- ↑ "Though the geographical extent of these rulers' power is not yet known in detail, according to Neog, the present-day North Lakhimpur district of Assam, which covers the find sites of most inscriptions, perhaps formed a part of their political dominion. If architectural continuity is admitted between the fortifications in the Sadiya region and the Burai river ruin site, it would be possible to believe that the kingdom of these rulers extended as far as the outer limit of Darrang district, to the westernmost extent of which Ahom conquerors settled the vanquished Chutiyas in the early part of the sixteenth century." (Shin 2020:52–53)

- ↑ "N.N Acharyya are of the opinion that the Chutiya kingdom extended up to Viswanath in the present Darrang district of Assam."(Datta 1985:28)

- ↑ "In the main, however, their territory was confined to the river valleys of the Suvansiri, Brahmaputra, Lohit, and the Dihing and hardly extended to the hills at its zenith." (Nath 2013:27)

- ↑ "The first confrontation between the Ahoms and the Chutiyas as a political power is mentioned in some chronicles such as the Deodhai Asam Buranji only during the reign of Ahom king Sutupha (1369–76), about a hundred years after the death of Sukapha." (Shin 2020:51)

- ↑ Dutta 1985, p. 29.

- ↑ "Rajadhara had a younger brother, Gandhara Bar-bhuya who did not settle in the Bardowa region, but collected a fairly large army and started on a expedition against the Khamtis and Chutiyas but he was foiled by the tribal chiefs and, retracing his steps, he settled at Nambarbhang (the modern Makhibaha)"(Neog 1980:66)

- ↑ (Neog 1980:51)

- ↑ "Both Habung and Panbari, neighbouring it, which was also, presumably ruled by a Bhuyan, were subjugated and annexed to the Ahom kingdom." (Baruah 1986:227)

- ↑ "He annexed Habung in 1512, a Chutiya dependency until then. Thereafter the whole of the Hinduized Chutiya Kingdom and parts of the present Nowgong district then ruled severally by baro-bhuyans and the Dimasa king,.."(Guha 1983:27)

- ↑ Baruah 1986, p. 227.

- 1 2 (Phukan 1992:55)

- ↑ "On the behalf of the Ahom king, they [Bhuyans] fought with and killed , the Kachari and Dhirnarayana, the Chutiya king"(Neog 1980:53)

- ↑ Baruah 1986, pp. 228–229.

- ↑ (Phukan 1992:56)

- ↑ "...the Ahom Buranji and the (Deodhai Asam Buranji) do not mention the name of Nitipal alias Chandranarayan. These sources ascribe the event to the reign of Dhirnarayan and state that in the final clash both the Chutiya king (Dhirnarayan) and the prince (Sadhaknarayan) were killed." (Baruah 1986:229f)

- ↑ (Neog 1980:53)

- ↑ "Besides, the items of Chutiya aristocracy like the Danda-Chhatra (royal umbrella), Arwan, Kekura-dola (Palaquin), embroidered-japi etc. were adopted by the Ahoms. The Chutiya kingdom had also several salt-springs at places like Borhat, which came under the Ahoms after its annexation"(Dutta 1985:30)

- 1 2 Baruah 1986, p. 230.

- ↑ Baruah 1986, p. 229.

- ↑ "(T)he outer limit of Darrang district, in the western-most extent of which Ahom conquerors settled the vanquished Chutiyas in the early part of the sixteenth century."(Shin 2020:53)

- ↑ (Sarma 1993:287) Dewanar Atla: "Suhungmung or Swarganarayan, after defeating Dhirnarayana and his minister Kasitora, received a number of Dola, Kali..Hiloi and gunpowder(Kalai-khar). Besides these, he also made a number of blacksmiths (Komar) prisoners and settled them either at Bosa (in present-day Jorhat district) or Ujjoni regions...It was only during the time of Suhungmung that the guild of blacksmiths and its trade started in Assam (Ahom kingdom). There were three thousand blacksmiths during this period."

- ↑ (Gait 1963:8) In 1525, Suhungmung proceeded in person to the Dihing country and appointed officers to administer the frontier provinces of Habung, Dihing, and Banlung.

- ↑ Hiteswar Borborua in his book Ahomor Dinmentions the firearms procured from Sadiya as Barud

- ↑ "(M)entions the capture of large quantity of fire arms from the Chutiyas. Hiteswar Barbarua• Ahomar Din,publication Board;Assam Guwahati 1981.p.450, mentions the capture of the best Chutiya cannon (Mitha Hulung Tup) after defeating them in 1523."(Buragohain 1988:62)

- ↑ Sharma, Benudhar.Maniram Dewan,p.289.

- ↑ Borboruah, Hiteswar (23 June 1997). "Ahomar Din Ed. 2nd" – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Sharma, Benudhar.Maniram Dewan,p.287. "After defeating the Chutia king and his minister Kasitora, Suhungmung or Dihingia Swarganarayan, apart from Dola, Kali,...,Cannons and Gunpowder, brought a great number of Blacksmiths as prisoners. These were settled at Bosha and the Ujoni regions; and smithies were set up where they were asked to build knives, daggers, swords, guns, and cannons. Saikias and Hazarikas were recruited among them to look after their work. It was only during this period that the work and trade of the blacksmith guild started in the kingdom. During the time of Dihingia raja, there were three thousand Blacksmiths."

- ↑ "Some Ahom (Assamese) chronicles (buranji) suggest that firearms were employed before this time. In 1505 or 1523, after having subdued the Chutiya, who dwelled in the region between Tibet and Assam, the Ahoms acquired firearms from them. The Chutiya may have received gunpowder technology from Tibet as well."(Laichen 2003:504)

- ↑ "The Chutiyas were engaged in all kinds of technical jobs of the Ahom kingdom. For example, the Khanikar Khel (guild of engineers) was always manned by the Chutiyas. The Jaapi-Hajiya Khel (guild for making Jaapis) was also monopolised by them. The Chutiyas being expert warrior knew the use of matchlocks. After their subjugation, the Chutiyas were, therefore engaged in manufacturing matchlocks and they became prominent in the Hiloidhari-Khel (guild for manufacturing matchlocks)"(Dutta 1985:30)

Bibliography

- Laichen, Sun (2003). "Military Technology Transfers from Ming China and the Emergence of Northern Mainland Southeast Asia (c. 1390–1527)". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press. 34 (3): 495–517. doi:10.1017/S0022463403000456. JSTOR 20072535. S2CID 162422482. Archived from the original on 6 August 2022. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- Neog, Maheswar (1980). Early History of the Vaiṣṇava Faith and Movement in Assam: Śaṅkaradeva and His Times. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. Archived from the original on 6 July 2023. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- Buragohain, Romesh (1988). Ahom State Formation in Assam: An Inquiry into the Factors of Polity Formation in Medieval North East India (PhD). North-Eastern Hill University. hdl:10603/61119.

- Baruah, Swarnalata (2007). Chutia Jatir Buranji (in Assamese).

- Baruah, S L (1986), A Comprehensive History of Assam, Munshiram Manoharlal

- Buragohain, Ramesh (2013). State formation in Early Medieval Assam:A case study of the Chutiya state (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 September 2020. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- Datta, S (1985). Mataks and their Kingdom (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- Gait, Sir Edward Albert (1963). A History of Assam. Thacker, Spink. Archived from the original on 6 July 2023. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- Gogoi, Jahnavi (2002). Agrarian System of Medieval Assam. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company.

- Gogoi, Kakoli (2011). "Envisioning Goddess Tara: A Study of the Tara Traditions in Assam". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 72: 232–239. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44146715.

- Guha, Amalendu (December 1983), "The Ahom Political System: An Enquiry into the State Formation Process in Medieval Assam (1228–1714)", Social Scientist, 11 (12): 3–34, doi:10.2307/3516963, JSTOR 3516963, archived from the original on 6 July 2023, retrieved 4 May 2020

- Jaquesson, François (2017). Translated by van Breugel, Seino. "The linguistic reconstruction of the past: The case of the Boro-Garo languages". Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area. 40 (1): 90–122. doi:10.1075/ltba.40.1.04van.

- Nath, D (2013), "State Formation in the Peripheral Areas: A Study of the Chutiya Kingdom in the Brahmaputra Valley", in Bhattarcharjee, J B; Syiemlieh, David R (eds.), Early States in North East India, Delhi: Regency Publications, pp. 24–49, ISBN 978-81-89233-86-0

- Neog, Maheswar (1977). "Light on a Ruling Dynasty of Arunachal Pradesh in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 58/59: 813–820. ISSN 0378-1143. JSTOR 41691751.

- Phukan, J. N. (1992), "Chapter III The Tai-Ahom Power in Assam", in Barpujari, H. K. (ed.), The Comprehensive History of Assam, vol. II, Guwahati: Assam Publication Board, pp. 49–60

- Saikia, Yasmin (2004). Fragmented Memories: Struggling to be Tai-Ahom in India. Duke University Press. ISBN 082238616X. Archived from the original on 1 February 2023. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- Sarma, Benudhar (1993), Maniram Dewan, Guwahati: Manuh Prakashan

- Shin, Jae-Eun (2020). "Descending from demons, ascending to kshatriyas: Genealogical claims and political process in pre-modern Northeast India, The Chutiyas and the Dimasas". The Indian Economic and Social History Review. 57 (1): 49–75. doi:10.1177/0019464619894134. S2CID 213213265.

- Momin, Mignonette (2006). Society and Economy in North-East India, Volume 2 : Socio-Economic Linkages in the decline of Pragjyotisa-Kamrupa. Department of History, NEHU Press. ISBN 9788189233341. Archived from the original on 6 July 2023. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- Dutta, Sristidhar (1985), The Mataks and their Kingdom, Allahabad: Chugh Publications