A chronographer was a graphical representation of historical information devised by American educator Emma Willard in the mid-19th century. The chronographers intended to show historical information in a geographic and chronological context. The first graphic was Picture of Nations, published in 1835, which showed civilizations as streams running through time, becoming wider and narrower as they gained or lost influence. She developed another chronographer, the Chronographer of American History, in 1844, showing the history of the United States as events marked on the branches of a tree.

Later chronographers showed historical events within an imagined Ancient Greek temple; the Temple of Time (1846), American Temple of Time (late 1840s), English Chronographer (1849) and Chronographer of Ancient History (1851) are examples of this type. In these chronographers the floor was occupied with the streams of civilizations, as in the Picture of Nations; the walls (often colonnaded) denoted the passage of time and were marked with historical leaders and the roof was split into categories to list other historic persons. The back wall of the temple was often marked as the point of biblical creation, sometimes with the date of 4004 BC from the Ussher chronology, though in her American Temple of Time a map of the continent is used. The birth of Christ was often denoted with a white star and other biblical figures included.

Willard's chronographers were intended as learning aids, allowing students to place themselves within the imaginary temple and to consider events in their historic and geographic context. She presented her chronographers at the Great Exhibition in London in 1851 and received a medal and certificate from Albert, Prince Consort. Willard's work has been disparaged by later writers, including for their almost complete omission of non-Western peoples and events.

Background

Emma Willard (1787–1870) became a teacher in her late teenage years and soon became a campaigner for reform of existing teaching methods, including for the teaching of subjects to girls which had before only been taught to boys.[1] Geography was one of the subjects that was deemed suitable for teaching to girls and Willard came to focus upon it. She approved of the works of Jedidiah Morse in this field and published a number of textbooks in conjunction with William Channing Woodbridge.[1][2]

Another of Willard's focuses was on history, she was one of the first to propose that American history be taught as a distinct subject from general history, arguing that it was critical to the survival of the young nation. By the 1820s the teaching of American history had been mandated in all publicly funded schools in five states. Interest in the subject grew over the next decades and Willard would go on to sell over a million history textbooks by the end of her life.[3]

Willard's textbooks reflected her geographical education; she considered that geography was, with chronology, one of the two "axes of history".[4] Willard was inspired partly by Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi's theories that advocated associating history to the neighbourhood of the student.[5] At a time when contemporary works failed to depict the geographical context of historical events her works contained many maps and other visual depictions of geography.[4] Willard's work had been inspired by the isotherm maps and charts developed by Alexander von Humboldt and, indeed, Willard and Woodbridge had incorporated some of Humboldt's illustrations in their geographical textbooks.[2] Willard's textbooks were unusual in their use of illustrations, even the early historical atlases then being published were largely collections of tables or charts.[6] One of her notable early graphics, regarded as a predecessor of the chronographers, was the Progress of the Roman Empire published in Willard and Woodbridge's 1824 A System of Universal Geography on the Principles of Comparison and Classification. This graphic depicted the tribes and civilizations absorbed by the Roman Empire as tributaries of the Amazon River, running from the top of the page to the bottom. Until this point timelines were usually presented in a left-to-right chronology.[7]

Willard, a strong American nationalist, became one of the first writers to produce national histories which focussed on events in a specific territory.[8] One of her works was the 1828 History of the United States, or Republic of America, in which she notably used a series of maps to chart the territorial expansion of the colonies and republic over a period of 250 years. This has also been described as a precursor to her chronographers.[9] Willard stood down from teaching in the 1840s, passing duties to her daughters, which allowed her to focus on the production of textbooks.[10]

Picture of Nations (1835)

Willard continued to develop her graphics as a means of placing historical events in geographic context and her publishers encouraged her as a means of differentiating her textbooks from others in a now-crowded market.[11] She created a class of graphics which she described as "chronographers", a depiction of historical events in a chronology with a geographic, though not strictly topographic, context.[11][12] She believed that information presented visually was more readily memorized than that presented in text.[7]

Willard's first chronographer was Picture of Nations, published in her 1835 Universal History.[13] Willard also referred to the chart as a "map of time".[7] The Picture of Nations attempted to depict all of human history on a single chart. It showed individual civilisations as streams running from biblical creation, which she dates to 4004 BC in accordance with the Ussher chronology, to the date of publication. The civilisations are not arranged according to strict geographical position but in accordance with their relationships to one another. Some, like China, are separated with thick black lines from other civilisations in an attempt to show their isolation. The width of the streams varies in an attempt to show the rise and fall of civilisations, in what she called the "ancestry of nations".[7]

The birth of Christ is shown as a bright star and marks the boundary between her ancient world and the middle ages. She marks the start of modern history with the 1492 landing of Christopher Columbus in the Americas.[13] The emergence of the United States, which is given one of the broadest widths of any civilisation at the bottom of the chart, is depicted as the culmination of human progress.[7]

The chronographer shows time as pyramidal in shape, narrow in the distant past and broader in the modern period. Willard explained this as an attempt to show how the importance of events diminishes with time passed.[13] The broader base allows her to show more detail of the periods of more relevance to contemporary students.[7] All of the leaders of the principal modern nations are shown while only a few of the most important persons of the ancient period are included.[13] Such an arrangement also allowed Willard to convey the sense that the passage of time had accelerated with the technological advancements following the industrial revolution, an aspect she found lacking in traditional linear timelines.[7]

Chronographer of American History (1844)

In 1844 Willard first published the Chronographer of American History within an updated version of her History of the United States.[14] This was also published the following year in large format, 4 by 6 feet (1.2 m × 1.8 m), for use as a teaching aid in classrooms.[7][15] While the tree analogy had been used before to depict historical events and family history Willard's was unusual in that it proceeded chronologically from left to right across the branches, rather than from root to branch.[7]

Willard's tree depicted the history of the United States from Columbus (1492) to the then modern time.[7] Willard separated the chronology into four "parts" (depicted as principal branches) the first of which ended with the New England Confederation of 1643, the second with the end of the French and Indian War in 1763, the third with the adoption of the Constitution of the United States in 1789 and the last part running to the publication date. The parts each have several smaller branches representing key events in American history.[14] The arrangement of branches was intended by Willard to organise the chaotic history of the United States into discrete parcels, conveying a sense of orderly progression. She ignored any mention of the impact upon Native Americans, or indeed any mention of pre-Columbian American history (which was poorly understood at the time).[7] Willard referred to the sky above the tree, where she placed her timeline scale, as the "circle of time". The ends of the branches touch this timeline to mark key dates.[7]

Willard included instructions to teachers with her Chronographer of American History. They were told to point to dates with a 4 feet (1.2 m) long, black-tipped "pointing rod".[15] The teacher was instructed to point the rod in a consistent manner and not allow the end to move while discussing a specific date to avoid confusing the students.[16] Students were to be encouraged to develop their own "internal" chronographer of key dates to aid memory.[15]

Willard was particularly fond of the Chronographer of American History and it featured in all subsequent editions of the History of the United States and she updated the work through her lifetime. The 1844 edition ended with the 1841 death of President William Henry Harrison and later versions with the 1846-48 Mexican–American War or the Compromise of 1850. Willard's last edition of the chronographer, created in 1861, ignored the American Civil War that was then in progress and she chose to label her last branch as 1860.[7]

Temple of Time (1846)

_Emma_Willard.jpg.webp)

Following good review for Picture of Nations, and inspired by the Greek Revival architectural movement, Willard developed it into the Temple of Time in 1846.[17] The streams of civilisations were relocated to the floor of an Ancient Greek temple, while the rest of the structure acts as a memory palace allowing the student to place themselves within the "vast imaginary edifice" and consider the geographical and chronological context of an historic event.[7][5] In Willard's caption she states: "the teacher or parent who shall place it before his pupils and children will find that they will insensibly become possesses of an inner 'Temple' in which they may, through life, deposite[sic], in the proper order of time, the facts of history as they shall acquire them. This we repeat is as important to the student of time as maps are to the student of place".[18] The mind palace is itself an ancient Greek technique that Willard had come across in her studies of Ancient Greek writings on history and memory.[5][18]

The temple is formed of two parallel lines of columns which recede into the distance, following conventional perspective.[17] Each column represents one century of time and they run back to the 4004 BC date for biblical creation, giving 59 pairs of columns.[18] The last set of columns are incomplete, to denote the date of publication.[19] The columns are marked with the names of "those sovereigns by which the age is chiefly distinguished". The columns support a roof on the underside of which are the names of significant figures in history. They are split into five categories: "statesmen; philosophers, discoverers &c; theologians &c; poets, painters &C and warriors", which are labelled on the pediment.[18] The rivers of time on the temple floor play a similar role to those in the Picture of Nations in depicting the geographical, cultural, political, economic, and military power of each civilisation as a proportion of the entire width of the floor.[17][20]

Barry Joyce, writing in 2015, notes that the technique "strikingly minimize[s] the overall importance of the United States", which is notable given Willard's nationalist and American exceptionalist views.[20] He also notes the interactive nature of the graphic which helped support the general strategy of her textbooks to encourage interrogation and dialogue.[19] Joyce describes the graphic as a "conceptual masterpiece" encouraging "a sort of fill-in-the-blank approach in which history is something unfinished, as you can see in the frontmost pillars of the temple of time".[5][19] Willard considered her work approximated "God's perspective" of history.[5]

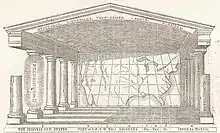

American Temple of Time (from late 1840s)

Willard conceived of an American history sequel to the Temple of Time in the late 1840s.[21] This was similar in design to the original except that the floor was divided into eight sections of varying widths representing the territory of the United States. These pieces were labelled as the Thirteen Colonies, New France, the Northwest Territory, Louisiana, Florida, Texas, Oregon and land ceded by Mexico.[22] The pillars of the temple represented the 15th-19th centuries and were engraved with the names of famous persons, Americans on the left pillars and Europeans on the right.[5] The roof was split into sections by century and class of person: statesmen, historians, theologians, poets and warriors.[23] The back wall of the temple was a map of North America running from the Pacific to Atlantic Oceans. It was sparse in geographical detail and was intended more as a logo of the country rather than a topographical resource.[24] Students were encouraged to redraw the temple and fill in the details such as shading in the floor to denote the acquisition of territory and adding labels for important battles.[7][19] Important figures were also to be added to the roof sections.[23]

Willard considered her American Temple of Time achieved "the goal, to which, step by step, I had been approaching" with regards to the teaching of American history.[23] Her views on the matter were framed by nationalism, a belief in manifest destiny and the right of settlers of European ancestry to displace native Americans.[7] This is evident in Willard's other works of this time; her History of the United States, Or Republic of America contained only two chapters on Native Americans and consigns them to a "timeless space prior to human history".[25]

English Chronographer (1849)

In 1849 Willard published an English Chronographer, similar in style to the Temple of Time and its American version. The graphic depicts the history of the British Empire within an Ancient Greek temple. The floor shows the development of the empire in several regions labelled: India, the Cape of Good Hope, New Holland, Jamaica, Gibraltar, Hanover, Great Britain, the Republic of America, Canada and France. The river format is reused, with nations forming and merging in streams. The floor is marked with the names of major national leaders and, at the far right, the names of key battles.[26]

The walls are solid and not colonnaded as in previous chronographers. The walls are marked in centuries back from the 19th century to the birth of Christ (which is again marked by a white star), beyond which they are un-numbered and only contain two entries. The left wall is annotated with key events and the right wall with a list of rulers of England from the first century. These are initially the Roman emperors, followed by the Heptarchy and the kings of England and Britain; the royal houses are named and coloured, the colour extending in a band across the roof and down the left wall. The roof is split into ten sections labelled: statesmen; philosophers, discoverers &c; historians &c; prose writers; theologians; poets; painters, sculptors, architects &c; admirals; remarkable women and warriors.[26]

Chronographer of Ancient History (1851)

In 1851 Willard produced a Chronographer of Ancient History depicting events in world history from biblical creation to the reign of Roman Emperor Augustus. The familiar format of the Ancient Greek temple is reused. The floor is once again marked with streams showing the rise and fall of civilisations and with key historical events and personalities. The far right section of the floor is marked with major conflicts. Solid black lines demark the 30th, 20th and 10th centuries BC. Prominent structures are shown on the floor, including iterations of the Temple in Jerusalem, the Parthenon and Egyptian Pyramids as well as the biblical Noah's Ark and Tower of Babel. Biblical creation is shown as the back wall of the temple, it is undated and at an undetermined number of centuries beyond the 40th century BC. The first events shown are the Ark and Tower of Babel which are dated to the 24th century BC, they are followed by the foundation of Babylon and Nineveh. There is relatively little detail on non-European civilizations: India and China are given only narrow sections of the floor, of constant width, and China has no events marked at all. The last events include the birth of Christ which is marked on the floor by a white star, this time labelled "the star of Bethlehem", and the foundation of the Roman Empire (described as encompassing "the civilized world").[27]

The temple walls are colonnaded with each column representing a century of time; they are numbered to the 40th century BC. The left columns are marked with a small number of significant events and the right columns with the names of major historical figures. The graphic notes that the rise of the Roman Empire is "coeval with that of Christianity". The temple roof is split into ten sections labelled: wise counsellors; philosophers, teachers &c; historians, orators &c; poets, musicians; the self-sacrificing; writers of the Old Testament &c; law givers & founders of states; painters, sculptors, architects &c; distinguished women; and warriors. The earliest figure is the mythological Chinese emperor Fuxi (labelled Fohi here), a number of biblical characters are also included.[27]

Legacy

Willard continued to revise her textbooks and chronographers throughout her life.[7] She exhibited the chronographers at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London; they were described as a "new and true method" of visualising history. Willard was afterwards awarded a medal and certificate from Albert, Prince Consort.[23] In 1854 she returned to London to represent the United States at the World's Educational Convention. Willard died on April 15, 1870.[28]

Willard's methods were disparaged by later educational writers.[14] The chronographers were criticised by literary historian Matt Cohen for ignoring the indigenous peoples of the Americas, or events and peoples of Africa and Asia. He says that where they are included, they exist only as "a vaguely hinted-at darkness, a shadowy uncivilization".[20]

References

- 1 2 Schulten, Susan (1 July 2007). "Emma Willard and the graphic foundations of American history". Journal of Historical Geography. 33 (3): 544. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2006.09.003. ISSN 0305-7488.

- 1 2 Schulten, Susan (1 July 2007). "Emma Willard and the graphic foundations of American history". Journal of Historical Geography. 33 (3): 548. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2006.09.003. ISSN 0305-7488.

- ↑ Schulten, Susan (1 July 2007). "Emma Willard and the graphic foundations of American history". Journal of Historical Geography. 33 (3): 546. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2006.09.003. ISSN 0305-7488.

- 1 2 Schulten, Susan (1 July 2007). "Emma Willard and the graphic foundations of American history". Journal of Historical Geography. 33 (3): 547. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2006.09.003. ISSN 0305-7488.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Joyce, Barry (2015). The First U.S. History Textbooks: Constructing and Disseminating the American Tale in the Nineteenth Century. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. p. 80. ISBN 978-1-4985-0216-0.

- ↑ Schulten, Susan (1 July 2007). "Emma Willard and the graphic foundations of American history". Journal of Historical Geography. 33 (3): 549. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2006.09.003. ISSN 0305-7488.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Schulten, Susan. "Emma Willard's Maps of Time". Public Domain Review. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ↑ Schulten, Susan (1 July 2007). "Emma Willard and the graphic foundations of American history". Journal of Historical Geography. 33 (3): 563. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2006.09.003. ISSN 0305-7488.

- ↑ Schulten, Susan (1 July 2007). "Emma Willard and the graphic foundations of American history". Journal of Historical Geography. 33 (3): 551. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2006.09.003. ISSN 0305-7488.

- ↑ Joyce, Barry (2015). The First U.S. History Textbooks: Constructing and Disseminating the American Tale in the Nineteenth Century. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-4985-0216-0.

- 1 2 Schulten, Susan (1 July 2007). "Emma Willard and the graphic foundations of American history". Journal of Historical Geography. 33 (3): 554. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2006.09.003. ISSN 0305-7488.

- ↑ Schulten, Susan (1 July 2007). "Emma Willard and the graphic foundations of American history". Journal of Historical Geography. 33 (3): 555. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2006.09.003. ISSN 0305-7488.

- 1 2 3 4 Schulten, Susan (1 July 2007). "Emma Willard and the graphic foundations of American history". Journal of Historical Geography. 33 (3): 557. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2006.09.003. ISSN 0305-7488.

- 1 2 3 Schulten, Susan (1 July 2007). "Emma Willard and the graphic foundations of American history". Journal of Historical Geography. 33 (3): 562. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2006.09.003. ISSN 0305-7488.

- 1 2 3 Joyce, Barry (2015). The First U.S. History Textbooks: Constructing and Disseminating the American Tale in the Nineteenth Century. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-4985-0216-0.

- ↑ Joyce, Barry (2015). The First U.S. History Textbooks: Constructing and Disseminating the American Tale in the Nineteenth Century. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-4985-0216-0.

- 1 2 3 Schulten, Susan (1 July 2007). "Emma Willard and the graphic foundations of American history". Journal of Historical Geography. 33 (3): 559. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2006.09.003. ISSN 0305-7488.

- 1 2 3 4 Buehler, Michael. "Emma Willard's Temple of Time". Boston Rare Maps. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Cohen, Matt (19 April 2019). "The Maps That Killed Alexander Posey". Textual Cultures. 12 (1): 83. doi:10.14434/TEXTUAL.V12I1.27149. JSTOR 26662805. S2CID 198097147.

- 1 2 3 Cohen, Matt (19 April 2019). "The Maps That Killed Alexander Posey". Textual Cultures. 12 (1): 79. doi:10.14434/TEXTUAL.V12I1.27149. JSTOR 26662805. S2CID 198097147.

- ↑ Schulten, Susan (1 July 2007). "Emma Willard and the graphic foundations of American history". Journal of Historical Geography. 33 (3): 560. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2006.09.003. ISSN 0305-7488.

- ↑ Schulten, Susan (1 July 2007). "Emma Willard and the graphic foundations of American history". Journal of Historical Geography. 33 (3): 561. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2006.09.003. ISSN 0305-7488.

- 1 2 3 4 Joyce, Barry (2015). The First U.S. History Textbooks: Constructing and Disseminating the American Tale in the Nineteenth Century. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-4985-0216-0.

- ↑ Schulten, Susan (1 July 2007). "Emma Willard and the graphic foundations of American history". Journal of Historical Geography. 33 (3): 564. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2006.09.003. ISSN 0305-7488.

- ↑ Cohen, Matt (19 April 2019). "The Maps That Killed Alexander Posey". Textual Cultures. 12 (1): 82. doi:10.14434/TEXTUAL.V12I1.27149. JSTOR 26662805. S2CID 198097147.

- 1 2 Willard, Emma (1849). Willard's English Chronographer or Chronology of Great Britain. New York: A S Barnes & Co.

- 1 2 "Mrs. Emma Willard's chronographer of ancient history, Troy, New York 1851 / lith. of Sarony 117 Fulton St. N. York". Library of Congress. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ↑ "Emma Willard". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 8 March 2021.