| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of China |

|---|

|

| Mythology and Folklore |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Music and Performing arts |

Chinese culture (simplified Chinese: 中华文化; traditional Chinese: 中華文化; pinyin: Zhōnghuá wénhuà) is one of the world's oldest cultures, originating thousands of years ago.[1][2] The culture prevails across a large geographical region in East Asia with Sinosphere in whole and is extremely diverse, with customs and traditions varying greatly between counties, provinces, cities, towns. The terms 'China' and the geographical landmass of 'China' have shifted across the centuries, before the name 'China' became commonplace in modernity.

Chinese civilization is historically considered a dominant culture of East Asia.[3] With China being one of the earliest ancient civilizations, Chinese culture exerts profound influence on the philosophy, virtue, etiquette, and traditions of Asia.[4] Chinese characters, ceramics, architecture, music, dance, literature, martial arts, cuisine, arts, philosophy, etiquette, religion, politics, and history have had global influence, while its traditions and festivals are celebrated, instilled, and practiced by people around the world.[5][6][7]

Identity

As early as the Zhou dynasty, the Chinese government divided Chinese people into four classes: gentry, farmer, craftsman, and merchant. Gentry and farmers constituted the two major classes, while merchant and craftsmen were collected into the two minor. Theoretically, except for the position of the Emperor, nothing was hereditary.

China's majority ethnic group, the Han Chinese, are an East Asian ethnic group and nation. They constitute approximately 92% of the population of China, 95% of Taiwan (Han Taiwanese),[8] 76% of Singapore,[9] 23% of Malaysia, and about 17% of the global population, making them the world's largest ethnic group, numbering over 1.3 billion people.

In modern China, there are 56 officially labelled ethnic groups.[10] Throughout Chinese history, many non-Han foreigners like the Indo-Iranians became Han Chinese through assimilation, other groups retained their distinct ethnic identities, or faded away.[11] At the same time, the Han Chinese majority has maintained distinct linguistic and regional cultural traditions throughout the ages. The term Zhonghua Minzu (simplified Chinese: 中华民族; traditional Chinese: 中華民族) has been used to describe the notion of Chinese nationalism in general. Much of the traditional identity within the community has to do with distinguishing the family name.

Regional

During the 361 years of civil war after the Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD), there was a partial restoration of feudalism when wealthy and powerful families emerged with large amounts of land and huge numbers of semi-serfs. They dominated important civilian and military positions of the government, making the positions available to members of their own families and clans.[12][13] The Tang Dynasty extended the imperial examination system as an attempt to eradicate this feudalism.[14] Traditional Chinese culture covers large geographical territories, where each region is usually divided into distinct sub-cultures. Each region is often represented by three ancestral items. For example, Guangdong is represented by chenpi, aged ginger and hay.[15][16] The ancient city of Lin'an (Hangzhou), is represented by tea leaf, bamboo shoot trunk, and hickory nut.[17] Such distinctions give rise to the old Chinese proverb: "十里不同風, 百里不同俗/十里不同風": "praxis vary within ten li, customs vary within a hundred li". The 31 provincial-level divisions of the People's Republic of China are grouped by its former administrative areas from 1949 to 1980, and are now known as traditional regions.

Social structure

Since the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors period, some form of Chinese monarch has been the main ruler above all. Different periods of history have different names for the various positions within society. Conceptually each imperial or feudal period is similar, with the government and military officials ranking high in the hierarchy, and the rest of the population under regular Chinese law.[18] From the late Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BCE) onwards, traditional Chinese society was organized into a hierarchic system of socio-economic classes known as the four occupations.

However, this system did not cover all social groups and the distinctions between the groups became blurred after the commercialization of Chinese culture in the Song dynasty (960–1279 CE). Ancient Chinese education also has a long history; ever since the Sui dynasty (581–618 CE), educated candidates prepared for the imperial examinations and exam graduates were drafted into government as scholar-bureaucrats. This led to the creation of a meritocracy, although success was available only to males who could afford test preparation. Imperial examinations required applicants to write essays and demonstrate mastery of the Confucian classics. Those who passed the highest level of the exam became elite scholar-officials known as jinshi, a highly esteemed socio-economic position. A major mythological structure developed around the topic of the mythology of the imperial exams. Trades and crafts were usually taught by a shifu. The female historian Ban Zhao wrote the Lessons for Women in the Han dynasty and outlined the four virtues women must abide by, while scholars such as Zhu Xi and Cheng Yi would expand on this. Chinese marriage and Taoist sexual practices are some of the rituals and customs found in society.

With the rise of European economic and military power beginning in the mid-19th century, non-Chinese systems of social and political organization gained adherents in China. Some of these would-be reformers totally rejected China's cultural legacy, while others sought to combine the strengths of Chinese and European cultures. In essence, the history of 20th-century China is one of experimentation with new systems of social, political, and economic organization that would allow for the reintegration of the nation in the wake of dynastic collapse.

Spiritual values

.jpg.webp)

Most spiritual practices are derived from Chinese Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism. The relative influence of each school of practice is a subject of debate and other practices, such as Neo-Confucianism, Buddhism and others, have been introduced. Reincarnation and other rebirth concepts are a reminder of the connection between real-life and the after-life. In Chinese business culture, the concept of guanxi, indicating the primacy of relations over rules, has been well documented.[19] While many deities are part of the tradition, some of the most recognized holy figures include Guan Yin, the Jade Emperor and Buddha.

Chinese Buddhism has shaped some Chinese art, literature and philosophy. The translation of a large body of foreign Buddhist scriptures into Chinese and the inclusion of these translations, together with works composed in China, into a printed canon had far-reaching implications for the dissemination of Buddhism throughout China. Chinese Buddhism is also marked by the interaction between Indian religions, Chinese folk religion, and Taoism.

Religion

During the Xia and Shang dynasties, Chinese religion was oriented to worshipping the supreme god Shang Di, with the king and diviners acting as priests and using oracle bones. The Zhou dynasty oriented religion to worshipping the broader concept of heaven. A large part of Chinese culture is based in the belief in a spiritual world. Countless methods of divination have helped answer questions, even serving as an alternative to medicine. Folklores have helped fill the gap between things that cannot be explained. There is often a blurred line between myth, religion and unexplained phenomenon. Many of the stories have since evolved into traditional Chinese holidays. Other concepts have extended beyond mythology into spiritual symbols such as Door god and the Imperial guardian lions. Along with the belief in the divine beings, there is belief in evil beings. Practices such as Taoist exorcism fighting mogwai and jiangshi with peachwood swords are just some of the concepts passed down from generations. A few Chinese fortune telling rituals are still in use today after thousands of years of refinement.

Taoism, a religious or philosophical tradition of Chinese origin, emphasizes living in harmony with the Tao (道, literally "Way", also romanized as Dao). The Tao is a fundamental idea in most Chinese philosophical schools; in Taoism, however, it denotes the principle that is the source, pattern and substance of everything that exists.[20][21] Taoism differs from Confucianism by not emphasizing rigid rituals and social order.[20] Taoist ethics vary depending on the particular school, but in general tend to emphasize wu wei (effortless action), "naturalness", simplicity, spontaneity, and the Three Treasures: 慈 "compassion", 儉/俭 "frugality", and 谦 "humility". The roots of Taoism can be traced back to at least the 4th century BCE. Early Taoism drew its cosmological notions from the School of Yinyang (Naturalists), and was deeply influenced by one of China's oldest texts, the Yijing, which expounds a philosophical system of human behavior in accordance with the alternating cycles of nature. The "Legalist" Shen Buhai may also have been a major influence, expounding a realpolitik of wu wei.[21][22][23] The Tao Te Ching, a compact book containing teachings attributed to Laozi (Chinese: 老子; pinyin: Lǎozǐ; Wade–Giles: Lao Tzu), is widely considered the keystone work of the Taoist tradition, together with the later writings of Zhuangzi.

Philosophy and legalism

Confucianism, also known as Ruism, was the official philosophy throughout most of Imperial China's history, and mastery of Confucian texts was the primary criterion for entry into the imperial bureaucracy. A number of more authoritarian strains of thought have also been influential, such as Legalism.There was often conflict between the philosophies, e.g. the Song dynasty Neo-Confucians believed Legalism departed from the original spirit of Confucianism. Examinations and a culture of merit remain greatly valued in China today. In recent years, a number of New Confucians (not to be confused with Neo-Confucianism) have advocated that democratic ideals and human rights are quite compatible with traditional Confucian "Asian values".[24]

Confucianism is described as tradition, a philosophy, a religion, a humanistic or rationalistic religion, a way of governing, or simply a way of life.[25] Confucianism developed from what was later called the Hundred Schools of Thought from the teachings of the Chinese philosopher Confucius (551–479 BCE), who considered himself a retransmitter of the values of the Zhou dynasty golden age of several centuries before.[26] In the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), Confucian approaches edged out the "proto-Taoist" Huang-Lao, as the official ideology, while the emperors mixed both with the realist techniques of Legalism.

Hundred Schools of Thought

The Hundred Schools of Thought were philosophies and schools that flourished from the 6th century to 221 BC, during the Spring and Autumn period and the Warring States period of ancient China.[27] While this period was fraught with chaos and bloody battles, it was an era of great cultural and intellectual expansion in China.[28] It came to be known as the Golden Age of Chinese philosophy because a broad range of thoughts and ideas were developed and could be freely discussed. This phenomenon has been called the Contention of a Hundred Schools of Thought (百家爭鳴/百家争鸣; bǎijiā zhēngmíng; pai-chia cheng-ming; "hundred schools contend"). The thoughts and ideas discussed and refined during this period have profoundly influenced lifestyles and social consciousness up to the present day in China and across East Asia. The intellectual society of this era was characterized by itinerant scholars, who were often employed by various state rulers as advisers on the methods of government, war, and diplomacy. This period ended with the rise of the imperial Qin Dynasty and the subsequent purge of dissent. A traditional source for this period is the Shiji, or Records of the Grand Historian by Sima Qian. The autobiographical section of the Shiji, the "Taishigong Zixu" (太史公自序), refers to the schools of thought described below.

Mohism was an ancient Chinese philosophy of logic, rational thought and science developed by the academic scholars who studied under the ancient Chinese philosopher Mozi (c. 470 BC–c. 391 BC). The philosophy is embodied in an eponymous book: the Mozi. Another group is the School of the Military (兵家; Bingjia) that studied warfare and strategy; Sunzi and Sun Bin were influential leaders. The School of Naturalists was a Warring States era philosophy that synthesized the concepts of yin-yang and the Five Elements; Zou Yan is considered the founder of this school.[29] His theory attempted to explain the universe in terms of basic forces in nature: the complementary agents of yin (dark, cold, female, negative) and yang (light, hot, male, positive) and the Five Elements or Five Phases (water, fire, wood, metal, and earth).

Language

The ancient written standard was Classical Chinese. It was used for thousands of years, but was mostly used by scholars and intellectuals in the upper class society called "shi da fu (士大夫)". It was difficult, but possible, for ordinary people to enter this class by passing written exams. Calligraphy later became commercialized, and works by famous artists became prized possessions. Chinese literature has a long past; the earliest classic work in Chinese, the I Ching or "Book of Changes", dates to around 1000 BC. A flourishing of philosophy during the Warring States period produced such noteworthy works as Confucius's Analects and Laozi's Tao Te Ching. (See also: Chinese classics) Dynastic histories were often written, beginning with Sima Qian's seminal Records of the Grand Historian, written from 109 BC to 91 BC. The Tang dynasty witnessed a poetic flowering, while the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature were written during the Ming and Qing dynasties. Printmaking in the form of movable type was developed during the Song dynasty. Academies of scholars sponsored by the empire were formed to comment on the classics in both printed and handwritten form. Members of Royalty frequently participated in these discussions.

Chinese philosophers, writers and poets were highly respected and played key roles in preserving and promoting the culture of the empire. Some classical scholars, however, were noted for their daring depictions of the lives of the common people, often to the displeasure of authorities.

Varieties of dialect and writing system

At the start of the 20th century, most of the population were still illiterate, and the many languages spoken (Mandarin, Wu, Yue (Cantonese), Min Nan (Ban-lam-gu), Jin, Xiang, Hakka, Gan, Hui, Ping etc.) in different regions prevented spoken communication with people from other areas. However, the written language made communication possible, such as passing on official orders and documents throughout the entire region of China. Reformers set out to establish a national language, settling on the Beijing-based Mandarin as the spoken form. After the May 4th Movement, Classical Chinese was quickly replaced by written vernacular Chinese, modeled after the vocabulary and grammar of the standard spoken language.[31]

Calligraphy

Chinese calligraphy is a form of writing (calligraphy), or, the artistic expression of human language in a tangible form. There are some general standardizations of the various styles of calligraphy in this tradition. Chinese calligraphy and ink and wash painting are closely related: they are accomplished using similar tools and techniques, and have a long history of shared artistry. Distinguishing features of Chinese painting and calligraphy include an emphasis on motion charged with dynamic life. According to Stanley-Baker, "Calligraphy is sheer life experienced through energy in motion that is registered as traces on silk or paper, with time and rhythm in shifting space its main ingredients."[32] Calligraphy has also led to the development of many forms of art in China, including seal carving, ornate paperweights, and inkstones.

In China, calligraphy is referred to as Shūfǎ (書法/书法), literally "the way/method/law of writing".[33] In Japan it is referred to as Shodō (書道/书道), literally "the way/principle of writing"; and in Korea as Seoye (서예; 書藝) literally "the skill/criterion[34] of writing". Chinese calligraphy is normally regarded as one of the "arts" (Chinese 藝術/艺术 pinyin: yìshù) in the countries where it is practised. Chinese calligraphy focuses not only on methods of writing but also on cultivating one's character (人品)[35] and taught as a discipline (書法; pinyin: shūfǎ, "the rules of writing Han characters"[36]).

Literature

The Zhou dynasty is often regarded as the touchstone of Chinese cultural development. Concepts covered in the Chinese classic texts include poetry, astrology, astronomy, the calendar, and constellations. Some of the most important early texts include the I Ching and the Shujing within the Four Books and Five Classics. Many Chinese concepts such as Yin and Yang, Qi, Four Pillars of Destiny in relation to heaven and earth were theorized in the pre-imperial periods. By the end of the Qing dynasty, Chinese culture had embarked on a new era with written vernacular Chinese for the common citizens. Hu Shih and Lu Xun were considered pioneers in modern literature at that time. After the founding of the People's Republic of China, the study of Chinese modern literature gradually increased. Modern-era literature has influenced modern interpretations of nationhood and the creation of a sense of national spirit.

Poetry in the Tang dynasty

Tang poetry refers to poetry written in or around the time of, or in the characteristic style of, China's Tang dynasty (18 June 618 – 4 June 907, including the 690–705 reign of Wu Zetian) or that follows a certain style, often considered the Golden Age of Chinese poetry. During the Tang dynasty, poetry continued to be an important part of social life at all levels of society. Scholars were required to master poetry for the civil service exams, but the art was theoretically available to everyone.[37] This led to a large record of poetry and poets, a partial record of which survives today. Two of the most famous poets of the period were Li Bai and Du Fu. Tang poetry has had an ongoing influence on world literature and modern and quasi-modern poetry. The Quantangshi ("Complete Tang Poems") anthology compiled in the early eighteenth century includes over 48,900 poems written by over 2,200 authors.[38]

The Quantangwen (全唐文, "Complete Tang Prose"), despite its name, contains more than 1,500 fu and is another widely consulted source for Tang poetry.[38] Despite their names, these sources are not comprehensive, and the manuscripts discovered at Dunhuang in the twentieth century included many shi and some fu, as well as variant readings of poems that were also included in the later anthologies.[38] There are also collections of individual poets' work, which generally can be dated earlier than the Qing anthologies, although few earlier than the eleventh century.[39] Only about a hundred Tang poets have such collected editions extant.[39] Another important source is anthologies of poetry compiled during the Tang dynasty, although only thirteen such anthologies survive in full or in part.[40] Many records of poetry, as well as other writings, were lost when the Tang capital of Changan was damaged by war in the eighth and ninth centuries, so that while more than 50,000 Tang poems survive (more than any earlier period in Chinese history), this still likely represents only a small portion of the poetry that was actually produced during the period.[39] Many seventh-century poets are reported by the 721 imperial library catalog as having left behind massive volumes of poetry, of which only a tiny portion survives,[39] and there are notable gaps in the poetic œuvres of even Li Bai and Du Fu, the two most celebrated Tang poets.[39]

Ci in Song dynasty

Ci (辭/辞) are a poetic form, a type of lyric poetry, done in the tradition of Classical Chinese poetry. Ci use a set of poetic meters derived from a base set of certain patterns, in fixed-rhythm, fixed-tone, and variable line-length formal types, or model examples: the rhythmic and tonal pattern of the ci are based upon certain, definitive musical song tunes. They are also known as Changduanju (長短句/长短句, "lines of irregular lengths") and Shiyu (詩餘/诗馀, "that which is beside poetry").Typically the number of characters in each line and the arrangement of tones were determined by one of around 800 set patterns, each associated with a particular title, called cípái 詞牌/词牌. Originally they were written to be sung to a tune of that title, with set rhythm, rhyme, and tempo. The Song dynasty was also a period of great scientific literature, and saw the creation of works such as Su Song's Xin Yixiang Fayao and Shen Kuo's Dream Pool Essays. There were also enormous works of historiography and large encyclopedias, such as Sima Guang's Zizhi Tongjian of 1084 or the Four Great Books of Song fully compiled and edited by the 11th century.

Notable Confucianists, Taoists and scholars of all classes have made significant contributions to and from documenting history to authoring saintly concepts that seem hundreds of years ahead of time. Although the oldest surviving textual examples of surviving ci are from 8th century CE Dunhuang manuscripts,[41] beginning in the poetry of the Liang dynasty, the ci followed the tradition of the Shi Jing and the yuefu: they were lyrics which developed from anonymous popular songs into a sophisticated literary genre; although in the case of the ci form some of its fixed-rhythm patterns have an origin in Central Asia. The form was further developed in the Tang dynasty. Although the contributions of Li Bo (also known as Li Po, 701 – 762) are fraught with historical doubt, certainly the Tang poet Wen Tingyun (812–870) was a great master of the ci, writing it in its distinct and mature form.[42] One of the more notable practitioners and developers of this form was Li Yu of the Southern Tang Dynasty during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. However, the ci form of Classical Chinese poetry is especially associated with the poetry of the Song Dynasty, during which it was indeed a popular poetic form. A revival of the ci poetry form occurred during the end of the Ming dynasty and the beginning of the Qing dynasty which was characterized by an exploration of the emotions connected with romantic love together with its valorization, often in a context of a brief poetic story narrative within a ci poem or a linked group of ci poems in an application of the chuanqi form of short story tales to poetry.[43]

Qu in Yuan dynasty

The Qu form of poetry is a type of Classical Chinese poetry form, consisting of words written in one of a number of certain, set tone patterns, based upon the tunes of various songs. Thus Qu poems are lyrics with lines of varying longer and shorter lengths, set according to the certain and specific, fixed patterns of rhyme and tone of conventional musical pieces upon which they are based and after which these matched variations in lyrics (or individual Qu poems) generally take their name.[44] The fixed-tone type of verse such as the Qu and the ci together with the shi and fu forms of poetry comprise the three main forms of Classical Chinese poetry. In Chinese literature, the Qu (Chinese: 曲; pinyin: qǔ; Wade–Giles: chü) form of poetry from the Yuan dynasty may be called Yuanqu (元曲 P: Yuánqǔ, W: Yüan-chü). Qu may be derived from Chinese opera, such as the Zaju (雜劇/杂剧), in which case these Qu may be referred to as sanqu (散曲). The San in Sanqu refers to the detached status of the Qu lyrics of this verse form: in other words, rather than being embedded as part of an opera performance the lyrics stand separately on their own. Since the Qu became popular during the late Southern Song dynasty, and reached a special height of popularity in the poetry of the Yuan dynasty, therefore it is often called Yuanqu (元曲), specifying the type of Qu found in Chinese opera typical of the Yuan dynasty era. Both Sanqu and Ci are lyrics written to fit a different melodies, but Sanqu differs from Ci in that it is more colloquial, and is allowed to contain Chenzi (襯字/衬字 "filler words" which are additional words to make a more complete meaning). Sanqu can be further divided into Xiaoling (小令) and Santao (散套), with the latter containing more than one melody.

The novels in Ming dynasty and Qing dynasty

The Four Great Classical[45] or Classic Novels of Chinese literature[46][lower-alpha 1] are the four novels commonly regarded by Chinese literary criticism to be the greatest and most influential of pre-modern Chinese fiction. Dating from the Ming and Qing dynasties, they are well known to most Chinese either directly or through their many adaptations to Chinese opera and other forms of popular culture. They are among the world's longest and oldest novels and are considered to be the pinnacle of China's literary achievement in classic novels, influencing the creation of many stories, plays, movies, games, and other forms of entertainment across other parts of East Asia.

Chinese fiction, rooted in narrative classics such as Shishuo Xinyu, Sou Shen Ji, Wenyuan Yinghua, Da Tang Xiyu Ji, Youyang Zazu, Taiping Guangji, and official histories, developed into the novel as early as the Song dynasty. The novel as an extended prose narrative which realistically creates a believable world of its own evolved in China and in Europe from the 14th to 18th centuries, though a little earlier in China. Chinese audiences were more interested in history and were more historically minded. They appreciated relative optimism, moral humanism, and relative emphasis on collective behavior and the welfare of the society.[48]

The rise of a money economy and urbanization beginning in the Song era led to a professionalization of entertainment which was further encouraged by the spread of printing, the rise of literacy, and education. In both China and Western Europe, the novel gradually became more autobiographical and serious in exploration of social, moral, and philosophical problems. Chinese fiction of the late Ming dynasty and early Qing dynasty was varied, self-conscious, and experimental. In China, however, there was no counterpart to the 19th-century European explosion of novels. The novels of the Ming and early Qing dynasties represented a pinnacle of classic Chinese fiction.[49] The scholar and literary critic Andrew H. Plaks argues that Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Water Margin, Journey to the West, and The Golden Lotus collectively constituted a technical breakthrough reflecting new cultural values and intellectual concerns. Their educated editors, authors, and commentators used the narrative conventions developed from earlier story-tellers, such as the episodic structure, interspersed songs and folk sayings, or speaking directly to the reader, but they fashioned self-consciously ironic narratives whose seeming familiarity camouflaged a Neo-Confucian moral critique of late Ming decadence. Plaks explores the textual history of the novels (all published after their author's deaths, usually anonymously) and how the ironic and satiric devices of these novels paved the way for the great novels of the 18th century.[50] Plaks further shows these Ming novels share formal characteristics.

Fashion and clothing

China's fashion history covers hundreds of years with some of the most colorful and diverse arrangements. Different social classes in different eras boast different fashion trends, the color yellow was usually reserved for the emperor during China's Imperial era.

Pre-Qing

From the beginning of its history, Han clothing (especially in elite circles) was inseparable from silk, supposedly discovered by the Yellow Emperor's consort, Leizu. The dynasty to follow the Shang, the Western Zhou Dynasty, established a strict hierarchical society that used clothing as a status meridian, and inevitably, the height of one's rank influenced the ornateness of a costume. Such markers included the length of a skirt, the wideness of a sleeve and the degree of ornamentation. In addition to these class-oriented developments, Han Chinese clothing became looser, with the introduction of wide sleeves and jade decorations hung from the sash which served to keep the yi closed. The yi was essentially wrapped over, in a style known as jiaoling youren, or wrapping the right side over before the left, because of the initially greater challenge to the right-handed wearer (people of Zhongyuan discouraged left-handedness like many other historical cultures, considering it unnatural, barbarian, uncivilized, and unfortunate). The Shang dynasty (c. 1600 BC – 1046 BC), developed the rudiments of Chinese clothing; it consisted of a yi, a narrow-cuffed, knee-length tunic tied with a sash, and a narrow, ankle-length skirt, called chang, worn with a bixi, a length of fabric that reached the knees. Vivid primary colors and green were used, due to the degree of technology at the time.

Qipao

During the Qing dynasty, China's last imperial dynasty, a dramatic shift of clothing occurred, examples of which include the cheongsam (or qipao in Mandarin). The clothing of the era before the Qing dynasty is referred to as Hanfu or traditional Han Chinese clothing. Many symbols such as phoenix have been used for decorative as well as economic purposes. Among them were the Banners (qí), mostly Manchu, who as a group were called Banner People (旗人 pinyin: qí rén). Manchu women typically wore a one-piece dress that retrospectively came to be known as the qípáo (旗袍, Manchu: sijigiyan or banner gown). The generic term for both the male and the female forms of Manchu dress, essentially similar garments, was chángpáo (長袍/长袍). The qipao fitted loosely and hung straight down the body, or flared slightly in an A-line. Under the dynastic laws after 1636, all Han Chinese in the banner system were forced to adopt the Manchu male hairstyle of wearing a queue as did all Manchu men and dress in Manchu qipao. However, the order for ordinary non-Banner Han civilians to wear Manchu clothing was lifted and only Han who served as officials were required to wear Manchu clothing, with the rest of the civilian Han population dressing however they wanted. Qipao covered most of the woman's body, revealing only the head, hands, and the tips of the toes. The baggy nature of the clothing also served to conceal the figure of the wearer regardless of age. With time, though, the qipao were tailored to become more form fitting and revealing. The modern version, which is now recognized popularly in China as the "standard" qipao, was first developed in Shanghai in the 1920s, partly under the influence of Beijing styles. People eagerly sought a more modernized style of dress and transformed the old qipao to suit their tastes. Slender and form fitting with a high cut, it had great differences from the traditional qipao. It was high-class courtesans and celebrities in the city that would make these redesigned tight fitting qipao popular at that time.[51] In Shanghai it was first known as zansae or "long dress" (長衫—Mandarin Chinese: chángshān; Shanghainese: zansae; Cantonese: chèuhngsāam), and it is this name that survives in English as the "cheongsam". Most Han civilian men eventually voluntarily adopted Manchu clothing while Han women continued wearing Han clothing. Until 1911, the changpao was required clothing for Chinese men of a certain class, but Han Chinese women continued to wear loose jacket and trousers, with an overskirt for formal occasions. The qipao was a new fashion item for Han Chinese women when they started wearing it around 1925.The original qipao was wide and loose. As hosiery in turn declined in later decades, cheongsams nowadays have come to be most commonly worn with bare legs.

Arts

Chinese art is visual art that, whether ancient or modern, originated in or is practiced in China or by Chinese artists. The Chinese art in the Republic of China (Taiwan) and that of overseas Chinese can also be considered part of Chinese art where it is based in or draws on Chinese heritage and Chinese culture. Early "Stone Age art" dates back to 10,000 BC, mostly consisting of simple pottery and sculptures. After this early period Chinese art, like Chinese history, is typically classified by the succession of ruling dynasties of Chinese emperors, most of which lasted several hundred years.

Chinese art has arguably the oldest continuous tradition in the world, and is marked by an unusual degree of continuity within, and consciousness of, that tradition, lacking an equivalent to the Western collapse and gradual recovery of classical styles. The media that have usually been classified in the West since the Renaissance as the decorative arts are extremely important in Chinese art, and much of the finest work was produced in large workshops or factories by essentially unknown artists, especially in Chinese ceramics.

Different forms of art have swayed under the influence of great philosophers, teachers, religious figures and even political figures. Chinese art encompasses all facets of fine art, folk art and performance art. Porcelain pottery was one of the first forms of art in the Palaeolithic period. Early Chinese music and poetry was influenced by the Book of Songs, and the Chinese poet and statesman Qu Yuan.

Chinese painting became a highly appreciated art in court circles encompassing a wide variety of Shan shui with specialized styles such as Ming dynasty painting. Early Chinese music was based on percussion instruments, which later gave away to stringed and reed instruments. By the Han dynasty papercutting became a new art form after the invention of paper. Chinese opera would also be introduced and branched regionally in addition to other performance formats such as variety arts.

Chinese lantern

The Chinese paper lantern (紙燈籠, 纸灯笼) is a lantern made of thin, brightly colored paper.[52] Paper lanterns come in various shapes and sizes, as well as various methods of construction. In their simplest form, they are simply a paper bag with a candle placed inside, although more complicated lanterns consist of a collapsible bamboo or metal frame of hoops covered with tough paper. Sometimes, other lanterns can be made out of colored silk (usually red) or vinyl. Silk lanterns are also collapsible with a metal expander and are decorated with Chinese characters and/or designs. The vinyl lanterns are more durable; they can resist rain, sunlight, and wind. Paper lanterns do not last very long, they soon break, and silk lanterns last longer. The gold paper on them will soon fade away to a pale white, and the red silk will become a mix between pink and red. Often associated with festivals, paper lanterns are common in China, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and similarly in Chinatowns with large communities of Overseas Chinese, where they are often hung outside of businesses to attract attention. In Japan the traditional styles include bonbori and chōchin and there is a special style of lettering called chōchin moji used to write on them. Airborne paper lanterns are called sky lanterns, and are often released into the night sky for aesthetic effect at lantern festivals.

The Chinese sky lantern (天燈, 天灯), also known as Kongming lantern, is a small hot air balloon made of paper, with an opening at the bottom where a small fire is suspended. In Asia and elsewhere around the world, sky lanterns have been traditionally made for centuries, to be launched for play or as part of long-established festivities. The name "sky lantern" is a translation of the Chinese name but they have also been referred to as sky candles or fire balloons. The general design is a thin paper shell, which may be from about 30 cm to a couple of metres across, with an opening at the bottom. The opening is usually about 10 to 30 cm wide (even for the largest shells), and is surrounded by a stiff collar that serves to suspend the flame source and to keep it away from the walls. When lit, the flame heats the air inside the lantern, thus lowering its density and causing the lantern to rise into the air. The sky lantern is only airborne for as long as the flame stays alight, after which the lantern sinks back to the ground.

Chinese hand fan

The oldest existing Chinese fans are a pair of woven bamboo, wood or paper side-mounted fans from the 2nd century BCE.[53] The Chinese character for "fan" (扇) is etymologically derived from a picture of feathers under a roof. A particular status and gender would be associated with a specific type of fan. During the Song dynasty, famous artists were often commissioned to paint fans. The Chinese dancing fan was developed in the 7th century. The Chinese form of the hand fan was a row of feathers mounted in the end of a handle. In the later centuries, Chinese poems and four-word idioms were used to decorate the fans by using Chinese calligraphy pens. In ancient China, fans came in various shapes and forms (such as in a leaf, oval or a half-moon shape), and were made in different materials such as silk, bamboo, feathers, etc.[54]

Carved lacquer

Carved lacquer or Qīdiāo (Chinese: 漆雕) is a distinctive Chinese form of decorated lacquerware. While lacquer has been used in China for at least 3,000 years,[55] the technique of carving into very thick coatings of it appears to have been developed in the 12th century CE. It is extremely time-consuming to produce, and has always been a luxury product, essentially restricted to China,[56] though imitated in Japanese lacquer in somewhat different styles. The producing process is called Diāoqī (雕漆/彫漆, carving lacquer).Though most surviving examples are from the Ming and Qing dynasties, the main types of subject matter for the carvings were all begun under the Song dynasty, and the development of both these and the technique of carving were essentially over by the early Ming. These types were the abstract guri or Sword-Pommel pattern, figures in a landscape, and birds and plants. To these some designs with religious symbols, animals, auspicious characters (right) and imperial dragons can be added.[55] The objects made in the technique are a wide range of small types, but are mostly practical vessels or containers such as boxes, plates and trays. Some screens and pieces of Chinese furniture were made. Carved lacquer is only rarely combined with painting in lacquer and other lacquer techniques.[57]

Later Chinese writers dated the introduction of carved lacquer to the Tang dynasty (618–906), and many modern writers have pointed to some late Tang pieces of armour found on the Silk Road by Aurel Stein and now in the British Museum. These are red and black lacquer on camel hide, but the lacquer is very thin, "less than one millimeter in thickness", and the effect very different, with simple abstract shapes on a plain field and almost no impression of relief.[58][59][60] The style of carving into thick lacquer used later is first seen in the Southern Song (1127–1279), following the development of techniques for making very thick lacquer.[61] There is some evidence from literary sources that it had existed in the late Tang.[62] At first the style of decoration used is known as guri (屈輪/曲仑) from the Japanese word for the ring-pommel of a sword, where the same motifs were used in metal, and is often called the "Sword-Pommel pattern" in English. This style uses a family of repeated two-branched scrolling shapes cut with a rounded profile at the surface, but below that a "V" section through layers of lacquer in different colours (black, red and yellow, and later green), giving a "marbled" effect from the contrasted colours; this technique is called tìxī (剔犀/剃犀) in Chinese. This style continued to be used up to the Ming dynasty, especially on small boxes and jars with covers, though after the Song only red was often used, and the motifs were often carved with wider flat spaces at the bottom level to be exposed.[63]

Folding screen

A folding screen (simplified Chinese: 屏风; traditional Chinese: 屏風) is a type of free-standing furniture. It consists of several frames or panels, which are often connected by hinges or by other means. It can be made in a variety of designs and with different kinds of materials. Folding screens have many practical and decorative uses. It originated from ancient China, eventually spreading to the rest of East Asia, Europe, and other parts of the world. Screens date back to China during the Eastern Zhou period (771–256 BCE).[64][65] These were initially one-panel screens in contrast to folding screens.[66] Folding screens were invented during the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE).[67] Depictions of those folding screens have been found in Han-era tombs, such as one in Zhucheng, Shandong Province.[64]

Folding screens were originally made from wooden panels and painted on lacquered surfaces, eventually folding screens made from paper or silk became popular too.[66] Even though folding screens were known to have been used since antiquity, it became rapidly popular during the Tang dynasty (618–907).[68] During the Tang dynasty, folding screens were considered ideal ornaments for many painters to display their paintings and calligraphy on.[65][66] Many artists painted on paper or silk and applied it onto the folding screen.[65] There were two distinct artistic folding screens mentioned in historical literature of the era. One of it was known as the huaping (simplified Chinese: 画屏; traditional Chinese: 畫屏; lit. 'painted folding screen') and the other was known as the shuping (simplified Chinese: 书屏; traditional Chinese: 書屏; lit. 'calligraphed folding screen').[66][68] It was not uncommon for people to commission folding screens from artists, such as from Tang-era painter Cao Ba or Song-era painter Guo Xi.[65] The landscape paintings on folding screens reached its height during the Song dynasty (960–1279).[64] The lacquer techniques for the Coromandel screens, which is known as kuǎncǎi (款彩 "incised colors"),[69] emerged during the late Ming dynasty (1368–1644)[70] and was applied to folding screens to create dark screens incised, painted, and inlaid with art of mother-of-pearl, ivory, or other materials.

Chinese jade

Chinese jade (玉) refers to the jade mined or carved in China from the Neolithic onward. It is the primary hardstone of Chinese sculpture. Although deep and bright green jadeite is better known in Europe, for most of China's history, jade has come in a variety of colors and white "mutton-fat" nephrite was the most highly praised and prized. Native sources in Henan and along the Yangtze were exploited since prehistoric times and have largely been exhausted; most Chinese jade today is extracted from the northwestern province of Xinjiang. Jade was prized for its hardness, durability, musical qualities, and beauty.[71] In particular, its subtle, translucent colors and protective qualities[71] caused it to become associated with Chinese conceptions of the soul and immortality.[72] The most prominent early use was the crafting of the Six Ritual Jades, found since the 3rd-millennium BC Liangzhu culture: the bi, the cong, the huang, the hu, the gui, and the zhang.[73] Although these items are so ancient that their original meaning is uncertain, by the time of the composition of the Rites of Zhou, they were thought to represent the sky, the earth, and the four directions. By the Han dynasty, the royal family and prominent lords were buried entirely ensheathed in jade burial suits sewn in gold thread, on the idea that it would preserve the body and the souls attached to it. Jade was also thought to combat fatigue in the living.[71] The Han also greatly improved prior artistic treatment of jade.[74] These uses gave way after the Three Kingdoms period to Buddhist practices and new developments in Taoism such as alchemy. Nonetheless, jade remained part of traditional Chinese medicine and an important artistic medium. Although its use never became widespread in Japan, jade became important to the art of Korea and Southeast Asia.

Mythological beings

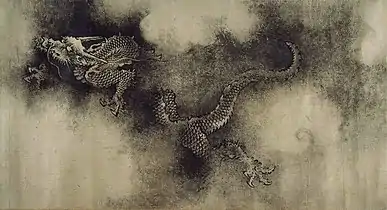

Loong

Loongs, also known as Chinese Dragon, are legendary creatures in Chinese mythology, Chinese folklore, and East Asian culture. Chinese dragons have many animal-like forms such as turtles and fish, but are most commonly depicted as snake-like with four legs. They traditionally symbolize potent and auspicious powers, particularly control over water, rainfall, typhoons, and floods. The dragon is also a symbol of power, strength, and good luck for people who are worthy of it. During the days of Imperial China, the Emperor of China usually used the dragon as a symbol of his imperial power and strength.[75] They are also the symbol and representative for the Son of Heaven, the Mandate of Heaven, the Celestial Empire and the Chinese Tributary System during the history of China.

Fenghuang

Fenghuang (鳳凰) are mythological birds found in Chinese and East Asian mythology that reign over all other birds. The males were originally called feng and the females huang but such a distinction of gender is often no longer made and they are blurred into a single feminine entity so that the bird can be paired with the Chinese dragon, which is traditionally deemed male. The fenghuang is also called the "August Rooster" (simplified Chinese: 鹍鸡; traditional Chinese: 鶤雞 or 鵾雞; pinyin: yùnjī or kūnjī; Wade–Giles: yün4-chi1 or k'un1-chi1) since it sometimes takes the place of the Rooster in the Chinese zodiac. In the Western world, it is commonly called the Chinese phoenix or simply Phoenix, although mythological similarities with the Western phoenix are superficial.

Qilin

The Qilin ([tɕʰǐ.lǐn]; Chinese: 麒麟), or Kirin in Japanese, is a mythical hooved chimerical creature in Chinese culture, said to appear with the imminent arrival or passing of a sage or illustrious ruler.[76] Qilin is a specific type of the lin mythological family of one-horned beasts. The earliest references to the qilin are in the 5th century BC Zuo Zhuan.[77][78] The qilin made appearances in a variety of subsequent Chinese works of history and fiction, such as Feng Shen Bang. Emperor Wu of Han apparently captured a live qilin in 122 BC, although Sima Qian was skeptical of this.[79]

Xuanwu

Xuanwu (Chinese:玄武) is one of the Four Symbols of the Chinese constellations. Despite its English name, it is usually depicted as a turtle entwined together with a snake. It is known as Genbu in Japanese and Hyeonmu in Korean. It represents the north and the winter season. In Japan, it is one of the four guardian spirits that protect Kyoto and it is said that it protects the city on the north. Represented by the Kenkun Shrine, which is located on top of Mt Funaoka in Kyoto. The creature's name is identical to that of the important Taoist god Xuanwu, who is sometimes (as in Journey to the West) portrayed in the company of a turtle and snake.

Music, instruments and dancing

-111425_(24150640974).jpg.webp)

Music and dance were closely associated in the very early periods of China. The music of China dates back to the dawn of Chinese civilization with documents and artifacts providing evidence of a well-developed musical culture as early as the Zhou dynasty (1122 BCE – 256 BCE). The earliest music of the Zhou dynasty recorded in ancient Chinese texts includes the ritual music called yayue and each piece may be associated with a dance. Some of the oldest written music dates back to Confucius's time. The first major well-documented flowering of Chinese music was exemplified through the popularization of the qin (plucked instrument with seven strings) during the Tang Dynasty, although the instrument is known to have played a major role before the Han Dynasty.

There are many musical instruments that are integral to Chinese culture, such as the Xun (Ocarina-type instrument that is also integral in Native American cultures), Guzheng (zither with movable bridges), guqin (bridgeless zither), sheng and xiao (vertical flute), the erhu (alto fiddle or bowed lute), pipa (pear-shaped plucked lute), and many others.

Dance in China is a highly varied art form, consisting of many modern and traditional dance genres. The dances cover a wide range, from folk dances to performances in opera and ballet, and may be used in public celebrations, rituals and ceremonies. There are also 56 officially recognized ethnic groups in China, and each ethnic minority group in China also has its own folk dances. The best known Chinese dances today are the Dragon dance and the Lion Dance.

Architecture

Chinese architecture is a style of architecture that has taken shape through the ages and influenced the architecture of East Asia for many centuries. The structural principles of Chinese architecture have remained largely unchanged, the main changes being only the decorative details. Since the Tang dynasty, Chinese architecture has had a major influence on the architectural styles of East Asia such as Japan and Korea. Chinese architecture, examples for which can be found from more than 2,000 years ago, is almost as old as Chinese civilization and has long been an important hallmark of Chinese culture. There are certain features common to Chinese architecture, regardless of specific regions, different provinces or use. The most important is symmetry, which connotes a sense of grandeur as it applies to everything from palaces to farmhouses. One notable exception is in the design of gardens, which tends to be as asymmetrical as possible. Like Chinese scroll paintings, the principle underlying the garden's composition is to create enduring flow, to let the patron wander and enjoy the garden without prescription, as in nature herself. Feng shui has played a very important part in structural development. The Chinese garden is a landscape garden style which has evolved over three thousand years. It includes both the vast gardens of the Chinese emperors and members of the imperial family, built for pleasure and to impress, and the more intimate gardens created by scholars, poets, former government officials, soldiers and merchants, made for reflection and escape from the outside world. They create an idealized miniature landscape, which is meant to express the harmony that should exist between man and nature.[80] A typical Chinese garden is enclosed by walls and includes one or more ponds, rock works, trees and flowers, and an assortment of halls and pavilions within the garden, connected by winding paths and zig-zag galleries. By moving from structure to structure, visitors can view a series of carefully composed scenes, unrolling like a scroll of landscape paintings.

Chinese palace

The Chinese palace is an imperial complex where the royal court and the civil government resided. Its structures are considerable and elaborate. The Chinese character gong (宮; meaning "palace") represents two connected rooms (呂) under a roof (宀). Originally the character applied to any residence or mansion, but it was used in reference to solely the imperial residence since the Qin dynasty (3rd century BC). A Chinese palace is composed of many buildings. It has large areas surrounded by walls and moats. It contains large halls (殿) for ceremonies and official business, as well as smaller buildings, temples, towers, residences, galleries, courtyards, gardens, and outbuildings. Apart from the main imperial palace, Chinese dynasties also had several other imperial palaces in the capital city where the empress, crown prince, or other members of the imperial family dwelled. There also existed palaces outside of the capital city called "away palaces" (離宮/离宫) where the emperors resided when traveling. Empress dowager Cixi (慈禧太后) built the Summer Palace or Yiheyuan (頤和園/颐和园 – "The Garden of Nurtured Harmony") near the Old Summer Palace, but on a much smaller scale than the Old Summer Palace.[lower-alpha 2]

Paifang

Paifang, also known as a Pailou, is a traditional style of Chinese architectural arch or gateway structure that is related to the Indian Torana from which it is derived.[81] The word paifang (Chinese: 牌坊; pinyin: páifāng) was originally a collective term for the top two levels of administrative division and subdivisions of ancient Chinese cities. The largest division within a city in ancient China was a fang (坊; fāng), equivalent to a current day ward. Each fang was enclosed by walls or fences, and the gates of these enclosures were shut and guarded every night. Each fang was further divided into several pai (牌; pái; 'placard'), which is equivalent to a current day (unincorporated) community. Each pai, in turn, contained an area including several hutongs (alleyways). This system of urban administrative division and subdivision reached an elaborate level during the Tang dynasty, and continued in the following dynasties. For example, during the Ming dynasty, Beijing was divided into a total of 36 fangs. Originally, the word paifang referred to the gate of a fang and the marker for an entrance of a building complex or a town; but by the Song dynasty, a paifang had evolved into a purely decorative monument.

Chinese garden

The Chinese garden is a landscape garden style which has evolved over the years.[82] It includes both the vast gardens of the Chinese emperors and members of the imperial family, built for pleasure and to impress, and the more intimate gardens created by scholars, poets, former government officials, soldiers and merchants, made for reflection and escape from the outside world. They create an idealized miniature landscape, which is meant to express the harmony that should exist between man and nature.[80] A typical Chinese garden is enclosed by walls and includes one or more ponds, rock works, trees and flowers, and an assortment of halls and pavilions within the garden, connected by winding paths and zig-zag galleries. By moving from structure to structure, visitors can view a series of carefully composed scenes, unrolling like a scroll of landscape paintings. The earliest recorded Chinese gardens were created in the valley of the Yellow River, during the Shang dynasty (1600–1046 BC). These gardens were large enclosed parks where the kings and nobles hunted game, or where fruit and vegetables were grown. Early inscriptions from this period, carved on tortoise shells, have three Chinese characters for garden, you, pu and yuan. You was a royal garden where birds and animals were kept, while pu was a garden for plants. During the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC), yuan became the character for all gardens.[83]

.jpg.webp)

The old character for yuan is a small picture of a garden; it is enclosed in a square which can represent a wall, and has symbols which can represent the plan of a structure, a small square which can represent a pond, and a symbol for a plantation or a pomegranate tree.[84] According to the Shiji, one of the most famous features of this garden was the Wine Pool and Meat Forest (酒池肉林). A large pool, big enough for several small boats, was constructed on the palace grounds, with inner linings of polished oval shaped stones from the sea shores. The pool was then filled with wine. A small island was constructed in the middle of the pool, where trees were planted, which had skewers of roasted meat hanging from their branches. King Zhou and his friends and concubines drifted in their boats, drinking the wine with their hands and eating the roasted meat from the trees. Later Chinese philosophers and historians cited this garden as an example of decadence and bad taste.[85]: 11 During the Spring and Autumn period (722–481 BC), in 535 BC, the Terrace of Shanghua, with lavishly decorated palaces, was built by King Jing of the Zhou dynasty. In 505 BC, an even more elaborate garden, the Terrace of Gusu, was begun. It was located on the side of a mountain, and included a series of terraces connected by galleries, along with a lake where boats in the form of blue dragons navigated. From the highest terrace, a view extended as far as Lake Tai, the Great Lake.[85]: 12

Martial arts

China is one of the main birthplaces of Eastern martial arts. Chinese martial arts, often named under the umbrella terms kung fu and wushu, are the several hundred fighting styles that have developed over the centuries in China. These fighting styles are often classified according to common traits, identified as "families" (家; jiā), "sects" (派; pài) or "schools" (门/門; mén) of martial arts. Examples of such traits include Shaolinquan (少林拳) physical exercises involving Five Animals (五形) mimicry, or training methods inspired by Old Chinese philosophies, religions and legends. Styles that focus on qi manipulation are called "internal "(內家拳/内家拳; nèijiāquán), while others that concentrate on improving muscle and cardiovascular fitness are called "external" (外家拳; wàijiāquán). Geographical association, as in "northern"(北拳; běiquán) and "southern" (南拳; nánquán), is another popular classification method.

Chinese martial arts are collectively given the name Kung Fu (gong) "achievement" or "merit", and (fu) "man", thus "human achievement") or (previously and in some modern contexts) Wushu ("martial arts" or "military arts"). China also includes the home to the well-respected Shaolin Monastery and Wudang Mountains. The first generation of art started more for the purpose of survival and warfare than art. Over time, some art forms have branched off, while others have retained a distinct Chinese flavor. Regardless, China has produced some of the most renowned martial artists including Wong Fei Hung and many others. The arts have also co-existed with a variety of weapons including the more standard 18 arms. Legendary and controversial moves like Dim Mak are also praised and talked about within the culture. Martial arts schools also teach the art of lion dance, which has evolved from a pugilistic display of Kung Fu to an entertaining dance performance.

Leisure

A number of games and pastimes are popular within Chinese culture. The most common game is Mahjong. The same pieces are used for other styled games such as Shanghai Solitaire. Others include pai gow, pai gow poker and other bone domino games. Weiqi and xiangqi are also popular. Ethnic games like Chinese yo-yo are also part of the culture where it is performed during social events.

Qigong is the practice of spiritual, physical, and medical techniques. It is as a form of exercise and although it is commonly used among the elderly, any one of any age can practice it during their free time.

Cuisine

Chinese cuisine is a very important part of Chinese culture, which includes cuisine originating from the diverse regions of China, as well as from Chinese people in other parts of the world. Because of the Chinese diaspora and historical power of the country, Chinese cuisine has influenced many other cuisines in Asia, with modifications made to cater to local palates.[86] Seasoning and cooking techniques of Chinese provinces depend on differences in historical background and ethnic groups. Geographic features including mountains, rivers, forests and deserts also have a strong effect on the local available ingredients, considering climate of China varies from tropical in the south to subarctic in the northeast. Imperial, royal and noble preference also plays a role in the change of Chinese cuisines. Because of imperial expansion and trading, ingredients and cooking techniques from other cultures are integrated into Chinese cuisines over time. The most praised "Four Major Cuisines" are Chuan, Lu, Yue and Huaiyang, representing West, North, South and East China cuisine correspondingly.[87] Modern "Eight Cuisines" of China[88] are Anhui, Cantonese, Fujian, Hunan, Jiangsu, Shandong, Sichuan, and Zhejiang cuisines.[89] Color, smell and taste are the three traditional aspects used to describe Chinese food,[90] as well as the meaning, appearance and nutrition of the food. Cooking should be appraised from ingredients used, cuttings, cooking time and seasoning. It is considered inappropriate to use knives on the dining table. Chopsticks are the main eating utensils for Chinese food, which can be used to cut and pick up food.

Tea culture

The practice of drinking tea has a long history in China, having originated there.[91] The history of tea in China is long and complex, for the Chinese have enjoyed tea for millennia. Scholars hailed the brew as a cure for a variety of ailments; the nobility considered the consumption of good tea as a mark of their status, and the common people simply enjoyed its flavour. In 2016, the discovery of the earliest known physical evidence of tea from the mausoleum of Emperor Jing of Han in Xi'an was announced, indicating that tea from the genus Camellia was drunk by Han dynasty emperors as early as 2nd century BC.[92] Tea then became a popular drink in the Tang (618–907) and Song (960–1279) Dynasties.[93]

Although tea originated in China, during the Tang dynasty, Chinese tea generally represents tea leaves which have been processed using methods inherited from ancient China. According to popular legend, tea was discovered by Chinese Emperor Shen Nong in 2737 BCE when a leaf from a nearby shrub fell into water the emperor was boiling.[94] Tea is deeply woven into the history and culture of China. The beverage is considered one of the seven necessities of Chinese life, along with firewood, rice, oil, salt, soy sauce and vinegar.[95] During the Spring and Autumn period, Chinese tea was used for medicinal purposes and it was the period when the Chinese people first enjoyed the juice extracted from the tea leaves that they chewed.

Chinese tea culture refers to how tea is prepared as well as the occasions when people consume tea in China. Tea culture in China differs from that in European countries such as Britain and other Asian countries like Japan in preparation, taste, and the occasions when people consume tea. Even today, tea is consumed regularly, both at casual and formal occasions. In addition to being a popular beverage, tea is used in traditional Chinese medicine, as well as in Chinese cuisine. Green tea is one of the main teas originating in China.

Food culture

Imperial, royal and noble preference played a role in the changes in Chinese cuisines over time.[96] Because of imperial expansion and trading, ingredients and cooking techniques from other cultures were integrated into Chinese cuisines over time. The overwhelmingly large variety of Chinese cuisine comes mainly from the practice of the dynastic periods, when emperors would host banquets with over 100 dishes per meal.[97] A countless number of imperial kitchen staff and concubines were involved in the food preparation process. Over time, many dishes became part of the everyday citizen's cuisine. Some of the highest quality restaurants with recipes close to the dynastic periods include Fangshan restaurant in Beihai Park Beijing and the Oriole Pavilion.[97] Arguably all branches of Hong Kong eastern style are in some ways rooted from the original dynastic cuisines.

Manhan Quanxi, literally Manchu Han Imperial Feast was one of the grandest meals ever documented in Chinese cuisine. It consisted of at least 108 unique dishes from the Manchu and Han Chinese culture during the Qing dynasty, and it is only reserved and intended for the Emperors. The meal was held for three whole days, across six banquets. The culinary skills consisted of cooking methods from all over Imperial China.[98] When the Manchus conquered China and founded the Qing dynasty, the Manchu and Han Chinese peoples struggled for power. The Kangxi Emperor wanted to resolve the disputes so he held a banquet during his 66th birthday celebrations. The banquet consisted of Manchu and Han dishes, with officials from both ethnic groups attending the banquet together. After the Wuchang Uprising, common people learned about the imperial banquet. The original meal was served in the Forbidden City in Beijing.[98]

Major subcultures

Chinese culture consists of many subcultures. In China, the cultural difference between adjacent provinces (and, in some cases, adjacent counties within the same province) can often be as big as than that between adjacent European nations.[99] Thus, the concept of Han Chinese subgroups (漢族民系/汉族民系, literally "Han ethnic lineage") was born, used for classifying these subgroups within the greater Han ethnicity. These subgroups are, as a general rule, classified based on linguistic differences.

Using this linguistic classification, some of the well-known subcultures within China include:

North

- Hui culture

- Culture of Beijing (京)

- Culture of Shandong (魯/鲁)

- Culture of Gansu

- Dongbei culture (東北/东北)

- Shaanxi culture

- Jin culture (晉/晋)[100][101][102]

- Zhongyuan culture (豫)

South

- Haipai culture (海)

- Hakka culture (客)

- Hokkien culture (閩)

- Hong Kong culture (港)

- Hubei culture (楚)

- Huizhou culture (徽)

- Hunanese culture (湘)

- Jiangxi culture (贛)

- Jiangnan culture

- Lingnan culture (粵/粤)

- Macanese culture

- Sichuanese culture (蜀)

- Taiwanese culture (台)

- Teochew culture (潮)

- Wenzhou culture (欧)

- Wuyue culture (吳/吴)

Gallery

A traditional red Chinese door with Imperial guardian lion knocker

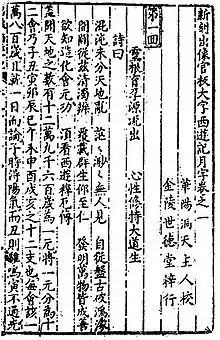

A traditional red Chinese door with Imperial guardian lion knocker Journey to the West (西遊記/西游记)

Journey to the West (西遊記/西游记) Xiqu performance

Xiqu performance Lion dance (舞狮)

Lion dance (舞狮) Dragon dance (舞龙)

Dragon dance (舞龙) Taoist architecture in China

Taoist architecture in China Wooden sculpture of Guanyin

Wooden sculpture of Guanyin Que pillar gates of Chongqing that once belonged to a temple dedicated to the Warring States period general Ba Manzi

Que pillar gates of Chongqing that once belonged to a temple dedicated to the Warring States period general Ba Manzi

Traditional clothing from the Ming dynasty

Traditional clothing from the Ming dynasty Hair Ornament, China, c. 19th century

Hair Ornament, China, c. 19th century Koi Pond is a signature scenery depicted in Chinese gardens

Koi Pond is a signature scenery depicted in Chinese gardens Oolong tea leaves steeping in a gaiwan

Oolong tea leaves steeping in a gaiwan Ming table in the Victoria and Albert Museum, 1425–1436

Ming table in the Victoria and Albert Museum, 1425–1436 Zhu-Ye-Qing-Tea

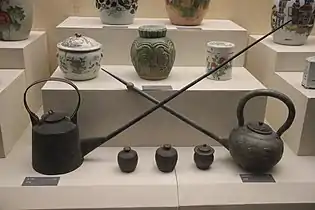

Zhu-Ye-Qing-Tea Dragon Tea Pot, Republic of China

Dragon Tea Pot, Republic of China Tea Pots, Republic of China

Tea Pots, Republic of China Laoshan green tea

Laoshan green tea Tea caddy, Chinese - Indianapolis Museum of Art

Tea caddy, Chinese - Indianapolis Museum of Art.jpg.webp) Chinese tea

Chinese tea Main hall and tea house in Dunedin Chinese Garden

Main hall and tea house in Dunedin Chinese Garden_-_1958.213.b_-_Cleveland_Museum_of_Art.jpg.webp) Chinese Export—European Market, 18th century - Tea Caddy (lid)

Chinese Export—European Market, 18th century - Tea Caddy (lid) Ancient China's Tea Pots

Ancient China's Tea Pots

See also

- Bian Lian

- Chinese animation

- Chinese ancestral veneration

- Chinese art

- Chinese Buddhism

- Chinese cinema

- Chinese clothes

- Chinese food

- Chinese dance

- Chinese dragon

- Chinese drama

- Chinese festival

- Chinese folklore

- Chinese folk religion

- Chinese garden

- Chinese instrument

- Chinese jade

- Chinese literature

- Chinese marriage

- Chinese name

- Chinese opera

- Chinese orchestra

- Chinese paper cutting

- Chinese sphere of influence

- Chinese studies

- Color in Chinese culture

- Customs and etiquette in Chinese dining

- Go

- I Ching's influence

- Numbers in Chinese culture

- Peking opera

- Science and technology in China

- Taoism

- Tian-tsui

- Xiangqi

Notes

References

- ↑ "Chinese Dynasty Guide – The Art of Asia – History & Maps". Minneapolis Institute of Art. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 10 October 2008.

- ↑ "Guggenheim Museum – China: 5,000 years". Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation & Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Archived from the original on 9 October 2009. Retrieved 10 October 2008.

- ↑ Walker, Hugh Dyson (2012). East Asia: A New History. AuthorHouse. p. 2.

- ↑ Wong, David (2017). "Chinese Ethics". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 11 March 2017. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ↑ "Chinese Culture, Tradition, and Customs – Penn State University and Peking University". elements.science.psu.edu. Archived from the original on 18 March 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ↑ "The original and unique culture of China". www.advantour.com. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ↑ "Chinese Culture: Ancient China Traditions and Customs, History, Religion". www.travelchinaguide.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ↑ Executive Yuan, Taiwan (2016). The Republic of China Yearbook 2016. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ↑ Population in brief 2015 (PDF) (Report). National Population and Talent Division. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ↑ Guo Rongxing (2011). China's Multicultural Economies: Social and Economic Indicators. Springer. p. vii. ISBN 978-1-4614-5860-9. Archived from the original on 22 October 2023. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ "Common traits bind Jews and Chinese". Asia Times Online. 10 January 2014. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ Robert Mortimer Marsh, Mandarins: The Circulation of Elites in China, 1600–1900, Ayer (June 1980), hardcover, ISBN 0-405-12981-5

- ↑ The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 13, p. 30.

- ↑ Rui Wang, The Chinese Imperial Examination System (2013) p. 3.

- ↑ "廣東三寶之一 禾稈草" [One of the Three Treasures of Guangdong Grass]. Huaxia.com. 26 March 2009. Archived from the original on 26 June 2009. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- ↑ "1/4/2008 three treasures" (PDF). RTHK.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- ↑ "說三與三寶" [Say "Three" and "Three Treasures"]. Xinhuanet.com. 19 March 2009. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- ↑ Mente, Boye De. [2000] (2000). The Chinese Have a Word for it: The Complete Guide to Chinese thought and Culture. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 0-658-01078-6

- ↑ Alon, Ilan, ed. (2003), Chinese Culture, Organizational Behavior, and International Business Management, Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishers.

- 1 2 Pollard, Elizabeth; Clifford; Robert; Rosenberg; Tignor (2011). Worlds Together Worlds Apart. New York, New York: Norton. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-393-91847-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 Creel (1970). What Is Taoism?. University of Chicago Press. pp. 48, 62–63. ISBN 978-0-226-12047-8. Archived from the original on 1 September 2023. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ↑ Benard, Elisabeth Anne (2010). Chinnamastā, the Aweful Buddhist and Hindu Tantric Goddess. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 978-81-208-1748-7. Archived from the original on 22 October 2023. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ↑ Ching, Julia; Guisso, R. W. L. (1991). Sages and Filial Sons: Mythology and Archaeology in Ancient China. Chinese University Press. ISBN 978-962-201-469-5. Archived from the original on 22 October 2023. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ↑ Bary, Theodore de. "Constructive Engagement with Asian Values". Archived from the original on 11 March 2005.. Columbia University.

- ↑ Yao (2000). An Introduction to Confucianism. Cambridge University Press. pp. 38–47. ISBN 978-0-521-64430-3. Archived from the original on 26 April 2023. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ↑ Rickett, Guanzi – "all early Chinese political thinkers were basically committed to a reestablishment of the golden age of the past as early Zhou propaganda described it."

- ↑ "Chinese philosophy" Archived 2 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopædia Britannica, Retrieved 4 June 2014

- ↑ Graham, A.C., Disputers of the Tao: Philosophical Argument in Ancient China (Open Court 1993). Archived 20 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 0-8126-9087-7

- ↑ "Zou Yan". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 26 April 2015. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ↑ Wurm, Li, Baumann, Lee (1987)

- ↑ Ramsey, S. Robert (1987). The Languages of China. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 3–16. ISBN 978-0-691-01468-5.

- ↑ Stanley-Baker (2010)

- ↑ 書 being here used as in 楷书/楷書, etc, and meaning "writing style".

- ↑ Wang Li; et al. (2000). 王力古漢語字典. Beijing: 中華書局. p. 1118. ISBN 7-101-01219-1.

- ↑ "Shodo and Calligraphy". Vincent's Calligraphy. Archived from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ↑ Shu Xincheng 舒新城, ed. Cihai (辭海 "Sea of Words"). 3 vols. Shanghai: Zhonghua. 1936.

- ↑ Jing-Schmidt, p. 256

- 1 2 3 Paragraph 15 in Paul W. Kroll "Poetry of the T'ang Dynasty", chapter 14 in Mair 2001.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Paragraph 16 in Paul W. Kroll "Poetry of the T'ang Dynasty", chapter 14 in Mair 2001.

- ↑ Paragraph 17 in Paul W. Kroll "Poetry of the T'ang Dynasty", chapter 14 in Mair 2001.

- ↑ Frankel, p. 216

- ↑ Davis, p. lxvii

- ↑ Zhang, pp. 76–80

- ↑ Yip, pp. 306–308

- ↑ Shep, Sydney J. (2011), "Paper and Print Technology", The Encyclopedia of the Novel, Encyclopedia of Literature, Vol. 2, John Wiley & Sons, p. 596, ISBN 978-1-4051-6184-8, archived from the original on 22 October 2023, retrieved 30 October 2017,

Dream of the Red Chamber... is considered one of China's four great classical novels...

- ↑ Li Xiaobing (2016), "Literature and Drama", Modern China, Understanding Modern Nations, Sta Barbara: ABC-CLIO, p. 269, ISBN 978-1-61069-626-5, archived from the original on 22 October 2023, retrieved 6 June 2020,

Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Outlaws of the Marsh, A Dream of Red Mansions, and Journey to the West have become the Four Great Classic Novels of Chinese literature.

- ↑ Cline, Eric; Takács, Sarolta Anna, eds. (2015), "Language and Writing: Chinese Literature", The Ancient World, Vol. V, Routledge, p. 508, ISBN 978-1-317-45839-5, archived from the original on 22 October 2023, retrieved 6 June 2020,

Chinese authors finally produced novels during the Yuan dynasty... when two of China's 'Four Classic Novels' – Water Margin and Romance of the Three Kingdoms – were published.

- ↑ Ropp, 1990, p. 310-311

- ↑ Ropp, 1990, p. 311

- ↑ Andrew H. Plaks, Four Masterworks of the Ming Novel (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1987), esp. pp. 497–98.

- ↑ "旗袍起源与哪个民族?". Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ↑ "Chinese lantern". The Free Dictionary. Archived from the original on 18 May 2014. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ↑ "articles – brief history of fans". aboutdecorativestyle.com. Archived from the original on 22 June 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- ↑ "Chinese Hand Fans". hand-fan.org. Archived from the original on 2 February 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- 1 2 Grove

- ↑ Grove; Cinnabar

- ↑ Watt and Ford, p. 3

- ↑ Watt and Ford, pp. 6–7 (p. 7 quoted)

- ↑ "armour / 盔甲 (MAS 621)". Collection online. The British Museum. See "Curator's comments". Archived from the original on 7 November 2017.

- ↑ Kuwayama, pp. 13–14 ; Rawson, p. 175 ; Grove, "Tang"

- ↑ Watt and Ford, p. 7 ; Rawson, p. 175

- ↑ Kuwayama, pp. 13–14

- ↑ Watt and Ford, pp. 26–27, 46–61, 60 for the use of green ; Rawson, p. 178 ; Grove, "Song" ; Kuwayama, pp. 13–17 on the Song

- 1 2 3 Handler, Sarah (2007). Austere luminosity of Chinese classical furniture. University of California Press. pp. 268–271, 275, 277. ISBN 978-0-520-21484-2. Archived from the original on 22 October 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Mazurkewich, Karen; Ong, A. Chester (2006). Chinese Furniture: A Guide to Collecting Antiques. Tuttle Publishing. pp. 144–146. ISBN 978-0-8048-3573-2. Archived from the original on 22 October 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Needham, Joseph; Tsien, Tsuen-hsuin (1985). Paper and printing, Volume 5. Cambridge University Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-521-08690-5. Archived from the original on 22 October 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- ↑ Lee, O-Young; Yi, Ŏ-ryŏng; Holstein, John (1999). Things Korean. Tuttle Publishing. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-8048-2129-2. Archived from the original on 22 October 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- 1 2 van Gulik, Robert Hans (1981). Chinese pictorial art as viewed by the connoisseur: notes on the means and methods of traditional Chinese connoisseurship of pictorial art, based upon a study of the art of mounting scrolls in China and Japan. Hacker Art Books. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-87817-264-1. Archived from the original on 22 October 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- ↑ 張世南 (Zhang Shi'nan) (1200s). "5". 遊宦紀聞 (yóuhuàn jìwén) (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 6 February 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

款謂陰字,是凹入者,刻畫成之 (kuǎn are inscriptions that are counter-relief, achieved by carving)

- ↑ Clunas, Craig (1997). Pictures and visuality in early modern China. London: Reaktion Books. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-86189-008-5. Archived from the original on 22 October 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 Fiero, Gloria K. The Humanistic Tradition 6th Ed, Vol. I. McGraw-Hill, 2010.

- ↑ Pope-Henessey, Chapter II.

- ↑ Pope-Henessey, Chapter IV.

- ↑ William Watson; Chuimei Ho (2007). Arts of China, 1600–1900. Yale University Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-300-10735-7. Archived from the original on 22 October 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- ↑ Ingersoll, Ernest; et al. (2013). The Illustrated Book of Dragons and Dragon Lore. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books.

- ↑ "qilin (Chinese mythology)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 19 October 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2011.