Charles Leale | |

|---|---|

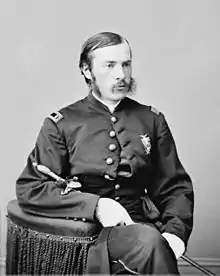

Charles Leale in his middle years | |

| Born | Charles Augustus Leale March 26, 1842 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died | June 13, 1932 (aged 90) Manhattan, New York, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Bellevue Hospital Medical College |

| Occupations |

|

| Spouse |

Rebecca Medwin Copcutt

(m. 1867; died 1923) |

| Children | 6 |

| Signature | |

Charles Augustus Leale (March 26, 1842 – June 13, 1932) was a surgeon in the Union Army during the American Civil War[1] and the first doctor to arrive at the presidential box at Ford's Theatre on April 14, 1865, after John Wilkes Booth fatally shot President Abraham Lincoln in the head. His prompt treatment allowed Lincoln to live until the next morning. Leale continued to serve in the army until 1866, after which he returned to his home town of New York City where he established a successful private practice and became involved in charitable medical care. One of the last surviving witnesses to Lincoln's death, Leale died in 1932 at the age of 90.

Early life

Dr. Leale was born in New York City March 26, 1842, the son of Captain William P. and Anna Maria Burr Leale. He was a grandson of Captain Richard Burr, who, in 1746 sent a cargo of corn to famine-stricken Ireland. Leale began his medical studies at 18, the private pupil of Dr. Austin Flint, Sr., in diseases of the heart and lungs, and of Dr. Frank H. Hamilton in gunshot wounds and surgery. He also studied at various clinics and served a full term as medical cadet in the United States Army.[2]

Assassination of Lincoln

In April 1865, about six weeks after graduating from Bellevue Hospital Medical College in New York City, Leale had charge of the Wounded Commissioned Officers' Ward at the United States Army General Hospital in Armory Square, Washington, DC.[3]

A few days before Lincoln's assassination, Leale saw Lincoln give his last public address and was intrigued by Lincoln's facial features. Soon after, learning that Lincoln was going to Ford's Theatre to see the play Our American Cousin, he attended as well – not to see the play, but to study Lincoln's face and facial expressions.[4] He arrived late and was unable to get a seat with an unhindered view of Lincoln; instead he sat near the front about forty feet away.

After John Wilkes Booth shot Lincoln, Leale rushed to Lincoln's box where he briefly examined Henry Rathbone, whom Booth had stabbed in the arm. He then saw Lincoln slumped in his armchair supported by Mary Todd Lincoln; Lincoln was unresponsive, barely breathing with no detectable pulse.[5] Initially thinking Lincoln had been stabbed, he laid him on the floor and, with bystander William Kent, cut off Lincoln's collar and opened his coat and shirt in search of wounds. After realizing that Lincoln's eyes were dilated, Leale found the bullet wound at the back of the head.[6] Leale was unable to locate the bullet, which was deep in Lincoln's head, but after he dislodged a blood clot Lincoln's breathing improved;[7]: 121–22 he found that regular removal of clots maintained Lincoln's breathing. He also gave artificial respiration. However, Leale knew from the beginning what would happen, and pronounced his assessment that Lincoln's wound "was mortal." By this time other surgeons from the audience had arrived, as well as actress Laura Keene, who cradled Lincoln's head, while Leale announced that Lincoln wasn't going to survive.

Fearing that Lincoln would not survive a carriage ride back to the White House, Leale ordered that Lincoln be moved to someplace nearby. He, along with two doctors and four soldiers, picked Lincoln up and slowly took him across to the Petersen House, where Leale and the others laid Lincoln diagonally on the small bed, rented by William Clark. After clearing everyone out, they searched for other wounds by removing all of Lincoln's clothes. When they realized that Lincoln's body was cold, they applied hot water bottles, mustard plasters, and blankets. At this point other physicians took charge of Lincoln's care, but Leale kept hold of Lincoln's hand throughout the night, "to let him know that he was in touch with humanity and had a friend."[8] Lincoln remained comatose until he died at 7:22 the next morning, April 15, 1865.

For his efforts, Leale was allowed to participate in various capacities during Lincoln's funeral.[4]

Later life

Although Leale submitted a report in 1867 to Representative Benjamin F. Butler's House commission investigating the assassination, Leale's account of Lincoln's death was not publicly revealed until the 100th anniversary of Lincoln's birth in 1909.[9] In that year Leale spoke on "Lincoln's Last Hour" to the New York commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States.[10] His 1865 written report to the Surgeon General of the United States was thought lost until 2008, when a 22-page photocopy was found in the Georgetown University Library and published.[11]

Seemingly written just hours after the assassination, a second copy was found in the National Archives in June 2012.[12][13][14]

After his discharge he went to Europe, where he studied the Asiatic Cholera. On September 3, 1867, he married Rebecca Medwin Copcutt, a daughter of Yonkers, New York, industrialist John Copcutt (1805–1895) at the historic John Copcutt Mansion.[15] Until his retirement in 1928, Dr. Leale maintained a continuous interest in philanthropic, medical, and scientific projects. Leale was one of the last surviving attendees of Lincoln's assassination upon his death in 1932 at the age of 90. He was survived by five children, a sixth child, daughter Annie Leale, having died in 1915. Rebecca Copcutt Leale died in 1923. He was a member of the Protestant Episcopal Church of the Heavenly Rest, where funeral services were held on June 15, 1932.[2] Burial followed in Oakland Cemetery.

The cuff of the shirt that Leale wore the night of the assassination, stained with Lincoln's blood, was later donated by his granddaughter to the National Museum of American History.[16]

See also

References

- ↑ Schroeder-Lein, Glenna R. (2015). The Encyclopedia of Civil War Medicine. Routledge. ISBN 9781317457107. Retrieved October 25, 2017 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 The New York Times, June 14, 1932, Obituary of Dr. Charles A. Leale.

- ↑ Leale, Charles. Lincoln's Last Hours. 1909. Project Gutenberg

- 1 2 Helen Leale Harper Jr. (Spring 1995). "Dr. Charles A. Leale: First Surgeon to Reach the Assassinated President Lincoln". YHS Newsletter. Yonkers Historical Society. Archived from the original on February 27, 2012. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- ↑ "Report of first doctor to reach shot Lincoln found".

- ↑ Richard A. R. Fraser, "How Did Lincoln Die?," American Heritage Magazine February/March 1995 "How Did Lincoln Die?" Archived April 7, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Steers, Edward. Blood on the Moon: The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln. University Press of Kentucky, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8131-9151-5

- ↑ Steers. Blood on the Moon. p. 14.

- ↑ Charles A. Leale to Benjamin F. Butler, July 20th, 1867, Benjamin Butler Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., box 43

- ↑ Charles A. Leale, Lincoln's Last Hours: Address Delivered Before the Commandery of the State of New York Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (New York: Privately published, 1909) Project Gutenberg (accessed July 27, 2012)

- ↑ Sotos, JG (2008). The Physical Lincoln Sourcebook. Mount Vernon, VA: Mt. Vernon Book Systems. ISBN 978-0-9818193-3-4.

- ↑ "Report of Dr. Charles A. Leale on Assassination, April 15, 1865". Archived from the original on December 24, 2013. Retrieved December 21, 2013.

- ↑ ""Is there a surgeon in the house?!" Papers of Abraham Lincoln researcher discovers report of Dr. Charles A. Leale, first physician to reach Lincoln at Ford's Theatre" (PDF). Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum. June 5, 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 11, 2012. Retrieved June 19, 2012.

- ↑ Papaioannou, Helena (June 6, 2012). "All Things Considered". National Public Radio (Interview). Interviewed by Robert Siegel. Retrieved June 19, 2012.

- ↑ Neil G. Larson (July 1985). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: John Copcutt Mansion". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on October 18, 2012. Retrieved December 24, 2010.

- ↑ "Coffee cups, chairs, and jackets: Presidential last moments preserved". National Museum of American History. October 13, 2017. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

External links

- Works by Charles Leale at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Charles Leale at Internet Archive

- Works by Charles Leale at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)