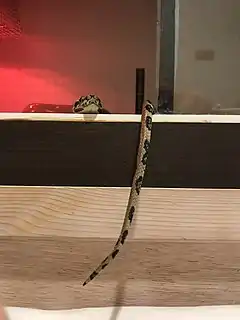

Caudal luring is a form of aggressive mimicry characterized by the waving or wriggling of the predator's tail to attract prey.[1] This movement attracts small animals who mistake the tail for a small worm or other small animal.[1] When the animal approaches to prey on the worm-like tail, the predator will strike.[1] This behavior has been recorded in snakes,[2] sharks,[3] and eels.[4]

Mimicry

The tail of a species may serve various functions, such as aggression, defense and feeding.[5] Caudal luring behavior was first recorded in 1878[6] and is an instance of aggressive mimicry.[7] Predators attract their prey by moving their caudal section to mimic a small animal, such as a worm, and attract prey animals.[1] The prey is intrigued by caudal movement and will investigate assuming it is their own prey, and the predator will strike.[5]

Species

Snakes

Caudal luring behavior is found in over 50 different snake species.[2] It is most common in boas, pythons, tropidophiids, colubrids and elapids of the genus Acanthophis, and the most evident in vipers and pit vipers, especially in rattlesnakes.[8][9][10] When the snake is foraging, it waits coiled up with its tail elevated and visible, wiggling around in a way that mimics a smaller animal and captures the attention of its prey.[1] Once the prey is in striking range, the snake attacks.[1] An immobile tail does not attract prey, confirming that it is the moving lure that tricks and attracts prey.[11] Caudal luring behavior is only elicited when prey are nearby.[11] Due to the tail resembling a writhing caterpillar and another worm-like insect larvae, the tail of the snake is often referred to as a vermiform.[2] Some species have developed elaborate lures to mimic a specific animal, such as the spider-tailed horned viper, which employs a highly modified tail to mimic a spider's form and locomotion.[12]

Of the snakes that practice the caudal luring behavior, 80% are juvenile.[13] The tails of juvenile snakes are typically conspicuously colored and fade to become more similar to the rest of the body with age.[1][14] This has been theorized to be an explanation for why caudal luring is most successful and prevalent in juveniles.[15] However, this explanation has been contested.[15] Experimental manipulation of Sistrurus miliarius’ tail color to make the tail match the rest of the juvenile's body revealed no significant difference in foraging success.[15] Another theory for juvenile success has been that their small tails are more effective lures compared to an adult's larger tail. Studies have confirmed that a smaller lure is more effective in attracting prey, as it is closer to the size of the worm-like prey.[11]

Sharks

Caudal luring also occurs in sharks, most common among Alopias vulpinus, Alopias superciliosus and Alopias pelagicus.[3] Their tails are all of varying shapes and sizes, but are all used to attract and immobilize prey.[3] Evidence of caudal luring comes from their diet, which consists largely of small schooling fishes which are susceptible to the luring strategy.[3]

The tasselled wobbegong (Eucrossorhinus dasypogon), a carpet shark, has a caudal fin that resembles a small fish with a small dark eyespot.[16] The caudal fin is waved slowly to attract and immobilize prey.[16][17]

Eels

Caudal luring is suspected to occur in the family Saccopharyngidae.[4] The caudal organs of these eels are luminous and equipped with filaments that would facilitate luring.[4] These eels prey solely on relatively large fishes, suggesting the use of a lure to trap their prey.[4]

Evolution

It has been suggested that caudal luring was involved in the evolution of the tail vibration rattle of rattlesnakes, a warning signal and a way of auditory communication, though this has been challenged.[18][19][20][5] Prey luring, in general, is confounded by false interpretation, as the wiggling of an appendage could have other behavioral meanings including aposematism, defense, or nervous release, and experimental evidence has been weak.[5][21][19]

Caudal luring is thought to have evolved from a caudally localized intention movement[19] (a behavior derived from locomotor movements). Essentially, the act of remaining stationary while sensing prey produces general nervous system excitation that gets released in the form of tail movements.[19] Caudal luring is not merely tail undulations, but must specifically be attractive to prey.[22] Caudal distraction is another behavior used by snakes, and the tail motions are similar to caudal luring.[22] The difference is in the snake's posture and especially in the nature and outcome of the behavior in reference to the encounter with prey.[22] Other caudal luring-like movements occur as warning signals and are induced by stressful circumstances.[5]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Heatwole, Harold; Davison, Elizabeth (1976). "A Review of Caudal Luring in Snakes with Notes on Its Occurrence in the Saharan Sand Viper, Cerastes vipera". Herpetologica. 32 (3): 332–336. ISSN 0018-0831. JSTOR 3891463.

- 1 2 3 Jackson, R. R.; Cross, F. R. (2013). "A cognitive perspective on aggressive mimicry: Aggressive mimicry". Journal of Zoology. 290 (3): 161–171. doi:10.1111/jzo.12036. PMC 3748996. PMID 23976823.

- 1 2 3 4 Aalbers, S. A.; Bernal, D.; Sepulveda, C. A. (May 2010). "The functional role of the caudal fin in the feeding ecology of the common thresher shark Alopias vulpinus". Journal of Fish Biology. 76 (7): 1863–1868. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2010.02616.x. ISSN 0022-1112. PMID 20557638. S2CID 205226057.

- 1 2 3 4 Nielsen, Jørgen G.; Bertelsen, E.; Jespersen, Åse (1989). "The Biology of Eurypharynx pelecanoides (Pisces, Eurypharyngidae)". Acta Zoologica. 70 (3): 187–197. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6395.1989.tb01069.x.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tiebout, Harry M. (1997). "Caudal Luring by a Temperate Colubrid Snake, Elaphe obsoleta, and Its Implications for the Evolution of the Rattle among Rattlesnakes". Journal of Herpetology. 31 (2): 290–292. doi:10.2307/1565399. JSTOR 1565399.

- ↑ "Short Notes". Amphibia-Reptilia. 23 (3): 343–374. 2002. doi:10.1163/15685380260449225. ISSN 0173-5373.

- ↑ Vane-Wright, R. I. (March 1976). "A unified classification of mimetic resemblances". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 8 (1): 25–56. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1976.tb00240.x.

- ↑ Chiszar, David; Boyer, Donal; Lee, Robert; Murphy, James B.; Radcliffe, Charles W. (September 1990). "Caudal Luring in the Southern Death Adder, Acanthophis antarcticus". Journal of Herpetology. 24 (3): 253. doi:10.2307/1564391. JSTOR 1564391.

- ↑ Carpenter, Charles C.; Murphy, James B.; Carpenter, Geoffrey C. (October 1978). "Tail Luring in the Death Adder, Acanthophis antarcticus (Reptilia, Serpentes, Elapidae)". Journal of Herpetology. 12 (4): 574. doi:10.2307/1563366. JSTOR 1563366.

- ↑ Labib, Ramzy S.; Awad, Ezzat R.; Farag, Nagi W. (January 1981). "Proteases of Cerastes cerastes (Egyptian sand viper) and Cerastes vipera (Sahara sand viper) snake venoms". Toxicon. 19 (1): 73–83. doi:10.1016/0041-0101(81)90119-7. ISSN 0041-0101. PMID 6784280.

- 1 2 3 Hagman, M.; Phillips, B. L.; Shine, R. (2008). "Tails of enticement: caudal luring by an ambush-foraging snake ( Acanthophis praelongus , Elapidae)". Functional Ecology. 22 (6): 1134–1139. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2435.2008.01466.x.

- ↑ Fathinia, Behzad; Rastegar-Pouyani, Nasrullah; Rastegar-Pouyani, Eskandar; Todehdehghan, Fatemeh; Amiri, Fathollah (2015). "Avian deception using an elaborate caudal lure in Pseudocerastes urarachnoides (Serpentes: Viperidae)". Amphibia-Reptilia. 36 (3): 223–231. doi:10.1163/15685381-00002997. Footage of the spider-tailed horned viper using its tail to lure a migrating bird featured in the Asia episode of the BBC series Seven Worlds, One Planet narrated by David Attenborough.

- ↑ Sazima, Ivan; Puorto, Giuseppe (February 1993). "Feeding Technique of Juvenile Tropidodryas striaticeps: Probable Caudal Luring in a Colubrid Snake". Copeia. 1993 (1): 222. doi:10.2307/1446315. ISSN 0045-8511. JSTOR 1446315.

- ↑ Labib, Ramzy S.; Awad, Ezzat R.; Farag, Nagi W. (January 1981). "Proteases of Cerastes cerastes (Egyptian sand viper) and Cerastes vipera (Sahara sand viper) snake venoms". Toxicon. 19 (1): 73–83. doi:10.1016/0041-0101(81)90119-7. ISSN 0041-0101. PMID 6784280.

- 1 2 3 Farrell, Terence M.; May, Peter G.; Andreadis, Paul T. (2011). "Experimental Manipulation of Tail Color Does Not Affect Foraging Success in a Caudal Luring Rattlesnake". Journal of Herpetology. 45 (3): 291–293. doi:10.1670/10-147.1. ISSN 0022-1511. S2CID 85107608.

- 1 2 Michael, Scott W. (2001). Aquarium sharks & rays : an essential guide to their selection, keeping, and natural history. T.F.H. ISBN 1890087572. OCLC 46449134.

- ↑ Ceccarelli, D. M.; Williamson, D. H. (February 2012). "Sharks that eat sharks: opportunistic predation by wobbegongs". Coral Reefs. 31 (2): 471. Bibcode:2012CorRe..31..471C. doi:10.1007/s00338-012-0878-z. ISSN 0722-4028.

- ↑ Schuett, Gordon W.; Clark, David L.; Kraus, Fred (May 1984). "Feeding mimicry in the rattlesnake Sistrurus catenatus, with comments on the evolution of the rattle". Animal Behaviour. 32 (2): 625–626. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(84)80301-2. S2CID 53177551.

- 1 2 3 4 Reiserer, R. S. (2002). "Stimulus control of caudal luring and other feeding responses: A program for research on visual perception in vipers". Biology of the Vipers. Eagle Mountain, Utah Eagle Mountain Publishing. 2002 (1): 361–383. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(84)80301-2. S2CID 53177551.

- ↑ Sisk, Norman R.; Jackson, James F. (August 1997). "Tests of Two Hypotheses for the Origin of the Crotaline Rattle". Copeia. 1997 (3): 485. doi:10.2307/1447554. JSTOR 1447554.

- ↑ Reiserer, Randall S.; Schuett, Gordon W. (September 2008). "Aggressive mimicry in neonates of the sidewinder rattlesnake, Crotalus cerastes (Serpentes: Viperidae): stimulus control and visual perception of prey luring". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 95 (1): 81–91. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2008.01016.x. ISSN 0024-4066.

- 1 2 3 Mulin, S. J. (1999). "Caudal distraction by rat snakes (Colubridae, Elaphe): A novel behaviour used when capturing mammalian prey". Great Basin Naturalist. 59: 361–367.