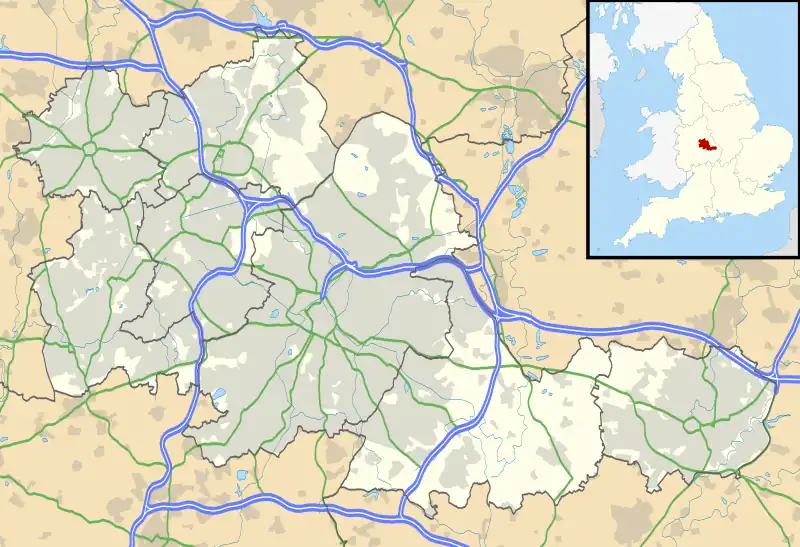

| Catherine-de-Barnes Isolation Hospital | |

|---|---|

Shown in West Midlands | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Catherine-de-Barnes, Solihull, England |

| Coordinates | 52°24′53″N 1°44′17″W / 52.414821°N 1.738189°W |

| Organisation | |

| Care system | NHS (from 1948) |

| Type | Quarantine |

| History | |

| Opened | 1910 |

| Closed | 1985 |

Catherine-de-Barnes Isolation Hospital was a specialist isolation hospital for infection control in Catherine-de-Barnes, a village within the Metropolitan Borough of Solihull in the English county of West Midlands.

Foundation

In 1907, a "fever hospital" was established as a joint operation of the Solihull and Meriden Councils for isolating patients with infectious diseases such as diphtheria, typhoid fever and smallpox.[1] A purpose-built isolation hospital was built by Solihull and Meriden Rural District Councils in Henwood Lane, Catherine-de-Barnes, and opened by 1910.[2] It was constructed with a main block housing individual one-bed wards and several separate bungalow-style buildings, enough to house ten staff and 16 patients.[3]

Maternity hospital

In the 1950s, when infectious diseases became less prevalent, Catherine-de-Barnes became a convalescent maternity hospital,[3] with the first child apparently being born there on 25 March 1953.[2]

National isolation hospital

Following the building of the maternity block at Solihull Hospital, Catherine-de-Barnes reverted to an isolation hospital.[3] It was designated the United Kingdom's national isolation hospital in 1966 and was kept on permanent standby for patients with highly dangerous diseases.[2] From the late 1960s to the late 1970s, the hospital was ready to accept patients at one hour's notice but had a resident staff of only two people, Leslie and Dorothy Harris. Anyone who wished to enter the 20 acre hospital grounds had to wear protective clothing and be inoculated.[3]

In 1978, Janet Parker, the last known victim of smallpox in the world, was treated and died at Catherine-de-Barnes Isolation Hospital following an outbreak that originated at the University of Birmingham Medical School.[1][2] The ward in which she died was still sealed off five years after her death, all the furniture and equipment inside left untouched.[3] Janet Parker's father, 71-year-old Frederick Witcomb, had died at Catherine-de-Barnes Hospital a week before his daughter after he had suffered a cardiac arrest while visiting her. No post-mortem was carried out on his body because of the risk of smallpox infection.[3][4]

Closure and sale

In 1981 the Department of Health and Social Security decided to close six other isolation hospitals around the country and spent £150,000 on maintenance at Catherine-de-Barnes. However, keeping the unit running at a cost of some £38,500 a year was seen as an expensive precaution,[3] and after the World Health Organization had declared smallpox extinct, the decision was made to mothball the Catherine-de-Barnes Hospital. In 1985 plans were considered to burn the hospital down (like Witton Isolation Hospital in 1967), thus ridding the land of any last traces of smallpox. The following year the fumigated hospital was sold to a building company.[3] In 1987, the hospital buildings were converted into a luxury housing development called Catherine Court.[2]

References

- 1 2 Tucker, Jonathan B. (2002). Scourge: the once and future threat of smallpox. New York: Grove Press. p. 129. ISBN 0-8021-3939-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Catherine-de-Barnes history, access date 12 August 2015

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Toxic SHOCK; Twenty five years ago a disease that many thought was dead and gone reared its head in Birmingham: smallpox. Campbell Docherty and Caroline Foulkes look back at the 1978 outbreak and ask if it could ever happen again. - Free Online Library". www.thefreelibrary.com.

- ↑ Geddes AM (2006). "The history of smallpox". Clinics in Dermatology. 24 (3): 152–7. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2005.11.009. PMID 16714195.