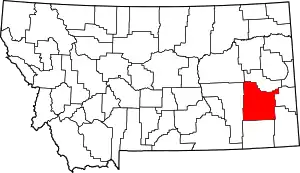

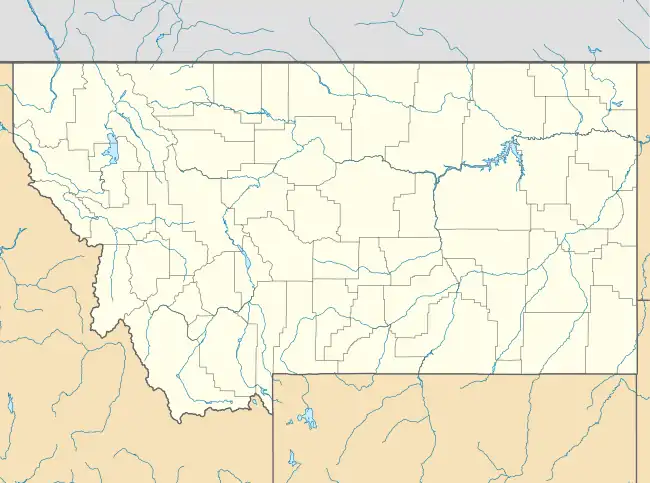

Carriage House Historic District | |

| |

| Location | Roughly bounded by Main, N. 9th, Palmer, N. 10th, Orr and N. 13th Sts. and Montana Ave. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 46°24′35″N 105°50′41″W / 46.40972°N 105.84472°W |

| Architect | Byron Vreeland |

| Architectural style | Late 19th And 20th Century Revivals, Late Victorian |

| NRHP reference No. | 91000720 |

| Added to NRHP | June 6, 1991[1] |

The Carriage House Historic District in Miles City, Montana was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1991.[1] The historic district contained 54 contributing buildings and 21 non-contributing ones, on the 900 to 1100 blocks of Pleasant and Palmer Avenues and on cross streets.[2] Nine locations feature signs describing the property.

Harmon House (1005 Palmer Street)

E. H. Johnson, state legislator and Miles City's first mayor, built this impressive modified Queen Anne style home in 1887. Attributed to Miles City architect Byron Vreeland, the irregular plan originally featured an elaborate arched porch and an elliptical bay capped by a conical roof. Rancher William Harmon, the home's second owner, built the carriage house in 1891. Third owner Senator Kenneth McLean, following current architectural trends, added Neo-classical details and a wraparound veranda between 1903 and 1910. Ella M. and David G. Rivenes purchased the property in 1962.[3]

Alderson House (1019 Palmer Street)

Nannie Alderson came to Montana from Kansas with her husband Walt in 1883. They operated a cattle ranch for a decade but moved to Miles City in 1893 so their children could attend school. In 1895, Walt died from head injuries after he was kicked by a horse. Left with four children between the ages of two and eleven, Nannie built this home for her family. She scraped by, selling home-baked bread and milk from the family's cow and catering meals. She also took in boarders. Nannie moved the family to Birney in 1902. Later in her life, Nannie earned wide acclaim for her pioneer reminiscence, A Bride Goes West, published in 1942. Her quaint wood-frame home retains its Greek Revival style footprint, once common in Miles City, but rarely preserved. Changes, including alteration of the front porch and the addition of side entry canopies in the 1910s, add an interesting layer. These reflect changing tastes and the growing popularity of the bungalow style in the early twentieth century.[3]

Emmanuel Episcopal Church

An eclectic blend of Romanesque, Gothic, and Queen Anne architectural styles, this 1886 church survives as designer Byron Vreeland's most significant building in Montana. Vreeland blended these styles as his architectural signature in many of his structures. The church features a barrel-vaulted wood ceiling trimmed with California redwood, a large Gothic style stained glass rose window in the entry gable above the canopy, and decorative brick work in a mouse-toothed pattern along the end elevations. The only alteration has been the removal of the bell tower. The interior features a walnut altar created from the salvaged hardwood finish of a steamboat that wrecked on the Buffalo Rapids below town about 1880. The altar is a rare survivor of steamboat architecture in Montana, the principal component of the “Wooden City” phase of building between 1878 and the early 1880s in Miles City. As the only known church designed by Vreeland, the Episcopal Church has continuously served the city for over a century and remains a unique work.[3]

Farnum House

Joseph E. Farnum arrived in Eastern Montana in 1883, settling in the Tongue River area. He married Minnie Parmenter in 1885 and relocated to a ranch on the Powder River. Typical of many ranchers at the time, Farnum maintained a residence in Miles City. He built a modest one-and-one-half-story Greek Revival style dwelling around 1883. In 1893, Farnum moved his family to town and shortly after completed a two-story addition in the Queen Anne style. He purchased C. A. Wiley's insurance and real estate business in 1901 and served as City Clerk in 1912. Farnum remained a prominent figure in Miles City until his death in 1924. Recognizing the importance of Miles City as a social, political, and economic center, Farnum built his home in the city's first affluent neighborhood and continued to alter the property to reflect the city's growth and prominence. Anna Weber purchased the property in 1928 and fortunately converted the residence into apartments. When she lost her savings in the Crash of 1929, the rental income assured her survival. The house was inherited by her niece after Weber's death and remains in the family to this day, having been converted back to a single family home.[3]

Furstnow House

Born in Wisconsin, Al Furstnow settled permanently in Miles City in 1894 and became the major saddler in the northwest. In 1895, Furstnow commissioned Byron Vreeland to build this Queen Anne style home, unusual because the architect usually designed in brick. The previous year Furstnow opened Al Furstnow's Saddle Shop on Main Street in a Vreeland-designed building. Credited with making the first flower hand-stamped saddles in Miles City for Britain's Lord Sidney Paget, Furstnow outfitted Leigh Remington of Remington Arms and Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show for their Paris exhibition. The bay window heads are embellished with carved medallions in a motif that is continued throughout the interior. The residence retains the original tall ceilings and detailing, including a fan-trimmed arch and four brass and stained-glass chandeliers, one being in the form of a British Crown. Remodeling in 1910 modernized the house with Craftsman details to reflect Miles City's financial status during the homestead boom. The home remained in the Furstnow family until the late 1980s.[3]

Kennie-Howe House (114 N 11th St)

The end of the 1880s witnessed development of Miles City's north side, with expensive homes being built on generous tracts of land. As land became scarce, parcels were carved from spacious lawns and working families became the neighbors of prominent residents. This charming Queen Anne style cottage, built on land once part of the property to the north, illustrates the trend. Constructed circa 1901, the home also foreshadows changing architectural tastes. Its symmetry reflects the newer Colonial Revival style while wide eaves suggest the Prairie style. Lovely stained glass transoms — a classic Queen Anne element — are, however, a dominant feature. The Craftsman style garage, constructed a little later to replace a barn, further chronicles neighborhood changes as transportation shifted from horse to automobile. Maud B. and Albert W. Kennie, later the longtime proprietors of the Olive Hotel, sold the home to rancher John S. Howe in 1904. The residence likely served as winter quarters so the Howe children could attend nearby Washington School.[3]

McAusland House (1013 Palmer St.)

Nestled amidst grand Queen Anne style houses is this early folk residence. The wooden home, constructed for Scottish immigrant John McAusland, appears on an 1883 bird's-eye map of Miles City. A steeply pitched side-gable roof and a small dormer dominate the home's façade. Originally, the dormer likely framed a door that led to the roof of a full-length front porch. The main part of the house is one-and-one-half stories; the kitchen is under a separate, one-story roof. This plan was common in the 1800s. Placing the kitchen under separate roof minimized fire risk. Bucket brigades could more easily reach a one-story roof, perhaps saving the rest of the house in case of a kitchen fire. The design also provided good ventilation, a boon during hot summers. McAusland arrived in Miles City from Deadwood, Dakota Territory, in 1882. In 1886, he was named postmaster, an appointment that reflects political connections. The plum patronage position paid $1,800 annually (equivalent to approximately $37,000 today). In later years, he worked as a clerk. He still lived here with his daughter in 1914.[3]

Methodist Church

In 1910, the Methodists hired a New York fundraising firm to raise funds for a new, larger church to replace the 1883 building. The growing congregation raised $14,000 and neighbor C. J. Wagenbreth donated the needed capital to complete the project, providing that no bell be hung in the belfry. Wagenbreth, not wanting to be awoken by bells, offered this deal, a steeple but no bells. Designed by the architectural firm of Woodruff & McGulpin in 1912, the Methodist Church stands as a visual reminder of the growth of Miles City and is an important neighborhood anchor. The building exhibits eclectic architectural influences, including Romanesque Revival windows, crenellated Gothic battlements, and early Christian or Tudor massing. Decorative round-arched Romanesque openings complement the bell tower and the design carries over to the main level windows. Each opening is highlighted with painted wood mullions and cusps that form a pair of arches with circular openings surrounded by brick. The only structure in Miles City designed by the firm, the design bears similarities to Brynjulf Rivenes’ Presbyterian Church on Main Street.[3]

Ulmer House (1003 Pleasant)

The elegance of this magnificent Neoclassical style mansion belies the humble roots of its first owner, George H. Ulmer, the Pennsylvania-born son of a German immigrant. Ulmer came to Miles City in 1883, and by 1889 partners George Miles and Charles Strevell had added Ulmer's name to their pioneer hardware firm. It became the largest hardware company in southeastern Montana. Helena-based architect Charles S. Haire designed the home for Ulmer and his wife, Flora, in 1902. Haire, whose talents contributed much to the local streetscape, was at that time frequently in Miles City supervising the design and construction of the Carnegie Library and the Ursuline Convent. These and the Ulmer residence showcase the architect's fluency in the Neoclassical style. Haire's design of this residence helped inspire a new trend in Miles City's domestic architecture. A grand semicircular entry porch, Ionic columns, Palladian windows, and a central pediment with an inset lunette are elements characteristic of the style. Very fine detailing includes molded pilasters, a carved wreath above the main entry, paneled oak doors, and beveled glass.[3]

References

- 1 2 "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ↑ Ellen and Ken Sievert (September 1990). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Carriage House Historic District". National Park Service. Retrieved July 30, 2017. With 19 photos from 1987-1990.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Montana National Register Historical Marker Sign Text". State of Montana. July 13, 2017. Archived from the original on August 2, 2017. Retrieved August 2, 2017.