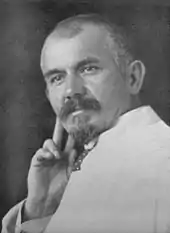

Carl Ludwig Seffner (19 June 1861 – 2 October 1932) was a German sculptor. He is best remembered for his statue of Johann Sebastian Bach at St. Thomas Church, Leipzig.

Early life and work

Born in 1861, Seffner studied at the Leipzig Academy of Art from 1877 to 1883. After a period in Berlin, from 1886 to 1888 he studied in Paris and Italy.[1] He returned to Leipzig in 1889, and for the next few years, worked for the University of Leipzig, where he produced the marble busts of Anton Springer, Karl Thiersch, Bernhard Windscheid and Carl Ludwig. After J.S. Bach's skull was found in 1894 during the building of St. John, Leipzig,[2] in 1895, Seffner and Wilhelm His were commissioned to produce an anatomical reconstruction.[3] The anatomical elements are attributed to His, while the shape work and painting are the work of Seffner.[2] The work earned him an honorary doctorate from the medical faculty of the University of Leipzig. The same year, Seffner became a member of the Masonic Lodge Minerva zu den drei Palmen.[4]

Commission

Seffner went on to produce sculptures of Karl Heine (1896/1897), the Mayor Carl Wilhelm Otto Koch (1898), young Johann Wolfgang von Goethe as a student in Leipzig (1902),[5] and Edvard Grieg (1904).[6] Additional works include the busts of Albert of Saxony, Alois Senefelder, and Friedrich Koenig.[7] After being elected an honorary member of the Leipzig Art Society in 1899[1] and the Dresden Art Academy in 1901.

In 1908, Seffner produced a statue of Bach, which stands near the proximity of the west entrance to St. Thomas Church.[8] Local art critic Arthur Smolian anticipated that Seffner's work would turn the city into a "Bayreuth of Bach's art" and attract pilgrims.[9] Of bronze, it measure 2.45 metres (8 ft 0 in) in height and sits on a 3.2-metre (10 ft) high socle. There is a music scroll in the statue's right hand and the left hand is raised from an organ manual. The statue debuted on 17 May 1908, coinciding with Leipzig's first Bach festival.[10] Seffner was also commissioned to produce numerous graves and stones for the South Cemetery in Leipzig. In the years before his death in Leipzig in 1932, he was an active member of the group of artists Leoniden.[11]

References

- 1 2 Schmidt - Theyer. Walter de Gruyter. 1 January 2005. p. 268. ISBN 978-3-11-096629-9.

- 1 2 Stefoff, Rebecca (2010). Forensic Anthropology. Marshall Cavendish. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-7614-4142-7.

- ↑ Wild, Michael (2010). Baedekeriana. Lulu.com. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-9565289-0-2.

- ↑ Förster, Otto Werner; Wolf, Hans-Joachim (1 January 1999). Ein Weltmann in Plagwitz und Schleussig: Carl Ernst Mey und die Deutsche Celluloid-Fabrik Actiengesellschaft (in German). Taurus. p. 11. ISBN 978-3-9805669-8-8.

- ↑ Pohlsander, Hans A. (2008). National Monuments and Nationalism in 19th Century Germany. Peter Lang. p. 115. ISBN 978-3-03911-352-1.

- ↑ Lawford-Hinrichsen, Irene (8 October 2008). Five hundred years to Auschwitz: a family odyssey from the Inquisition to the present. Edition Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-9536112-1-8.

- ↑ International Publishers Association (1902). Rapports (Public domain ed.). Associazione Tipografico-libraria Italiana. pp. 342–.

- ↑ Erickson, Raymond (2009). The Worlds of Johann Sebastian Bach. Amadeus Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-1-57467-166-7.

- ↑ Varwig, Bettina (3 November 2011). Histories of Heinrich Schütz. Cambridge University Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-139-50201-6.

- ↑ Pohlsander, Hans A. (2008). National Monuments and Nationalism in 19th Century Germany. Peter Lang. p. 123. ISBN 978-3-03911-352-1.

- ↑ Möbus, Frank (2000). Ringelnatz: ein Dichter malt seine Welt (in German). Wallstein Verlag. p. 19. ISBN 978-3-89244-337-7.