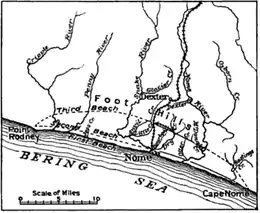

Cape Nome is a headland on the Seward Peninsula in the U.S. state of Alaska. It is situated on the northern shore of Norton Sound, 15 miles (24 km) to the east of Nome also on Norton Sound. It is delimited by the Norton Sound to the south, Hastings Creek on the west, a lagoon on the east and an estuary formed by the Flambeau River and the Eldorado River. From the sea shore, Cape Nome extends inland by about 4 miles (6.4 km), connected by road with Nome.[1]

Etymology

Named Tolstoi ((in Russian) "blunt" or "broad") by Mikhail Tebenkov (1833), it was named Sredul ("middle") on an 1852 Russian Hydrographic Service chart, with Tolstoi added as a synonym. The name Nome, used by Henry Kellett in 1849, first appears on British Admiralty charts after the John Franklin search expeditions. In 1901, Sir William Wharton wrote: "The name Cape Nome, which is off the entrance to Norton bay, first appears on our charts from an original of Kellett in 1849. I suppose the town gets its name from the same source, but what that is we have nothing to show." Another interpretation, by the geographer George Davidson, is that a draftsman may have misinterpreted the notation "? Name" as "C. Nome".[2]

History

Cape Nome is located 129 miles (208 km) to the south east of the Bering Strait. The western extension of the North America and the eastern extension of Asia are separated by the waters of the strait. It is reported that a bridge connected the two parts some years back and that the people of the two regions interacted and trading contacts existed during the start of the Christian era. In 1791 and 1861, Commodore Joseph Billings and Otto van Koztebue carried out explorations close to Cape Nome. A trading post was established at St. Michael along a sea route of 130 miles (210 km) from Cape Nome and by a land route of 225 miles (362 km).[3]

Prior to the discovery of gold at Cape Nome, a mission had been established for a number of years at the cape where one of the Government reindeer herds was maintained.[4] Placer gold was discovered on Snake River in 1898 by a party which started from Golovnin Bay to prospect the gravels of Sinuk River. A rush to the region took place immediately after the news reached the miners about Golovnin Bay, and on October 18, the Cape Nome mining precinct was formed.[5]

An Eskimo village with a population of 80 was named in the cape. It was given the name as Ayacheruk in the text while the map spelled it as Aiacheruk.[6]

Geography

Cape Nome is a blunt, rocky headland on Seward Peninsula. The shore line between Cape Nome and Topkok is marked by large lagoons. West of Cape Nome, the shoreline, as far as Cape Rodney, is almost straight and uninterrupted except for the tidal inlets at the mouths of the larger rivers. Near the coast between Sinuk River and the flat-topped promontory of Cape Nome is a well-marked bench at an altitude of about 700 feet (210 m).[7] The shore line may formerly have extended from the hills west of Cripple River to Cape Nome, and probably formed a broad arc of fairly uniform curvature, like the present beach, but with smaller radius. The elevation of the depression between Cape Nome and Army Peak is 115 feet (35 m). Bed rock is traced northwestward from Cape Nome for a distance of nearly 5 miles (8.0 km), and in the low rounded hill between Hastings and Saunders creeks has an elevation of 297 feet (91 m). Between this point and the Army Peak schist mass, still farther to the northwest, is an interval of about 3 miles (4.8 km) across a broad, low saddle where no rocks are exposed. The Nome tundra gravels occupy the crescent-shaped lowland extending from Cape Nome to the hills west of Cripple River. The coastal plain or tundra gravel occupies the crescent-shaped area included between the sea and the hills and extending from Cape Nome to Rodney Creek, 14 miles (23 km) west of the mouth of Snake River.[5] Lagoons shut off from the sea by sand bars may be seen east of Cape Nome.[8]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 60 | — | |

| 1890 | 41 | −31.7% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[9] | |||

Cape Nome first appeared on the 1880 U.S. Census as the unincorporated Inuit village of "Ayacheruk" (with alternative spellings of Ahyoksekawik and Aiacheruk). All 60 residents were Inuit.[10] In 1890, it returned as Cape Nome including the native villages of Ahyoksekawik (Ayacheruk) & Kogluk. All 41 residents were native.[11] It did not appear again on the census.

Geology

The granite formations of the Cape Nome and the greenstone formations which occur in the form of dykes and sills that intrude into the limestone and schist formations of the Nome, are interpreted as an intrusive form of green stone only. However, Cape Nome represents a large geological formation of granites seen in the seaward face of the Cape. It also has intrusions of green stone and porphyritic rocks with feldspar crystals. Allanite, epidote, secondary minerals like chlorite and albite are also discerned. Minor quartz fillings are noticed in feldspar crystals. The Metamorphosis process, which has resulted in the biotite formation attaining a fine grained status that gives the appearance of a banded gneissic structure. The feldspar crystals found in the granite, generally of 1 to.1.5 inches diameter, have intruded into both granitic and gneissic formations.[5]

The seaward face of Cape Nome is part of the Nome quadrangle, and is spread over an area of 3.75 square miles (9.7 km2), along a boundary contact zone noted here. Another feature recorded during field on observations is that granite has become the feldspathic schist near the boundary on the northern side of the cape. A microscopic examination of the samples of feldspar intrusions in granite of the Cape have indicated that the large crystals of orthoclase feldspar have principal minerals of quartz, orthoclase, microcline, albite, epidote, and biotite.[5]

Establishing the age of the granite formations of Cape Nome and its geological link with the granites of Kigluaik Mountains has not been possible, due to the fact that the intrusions took place over eons.[5]

In 1947, a field party of the Geological Survey carried out a brief study of the area to ascertain and confirm the earlier claims (a 1946 tracer study) of finding allanite and also radioactive minerals in the Cape Nome granites. The study was conducted as the Cape Nome area was easily accessible on the Seaward Peninsula. The studies in 1947 did not confirm the presence of allanite or radioactive mineral in the granites.[1]

Archaeological studies

Archaeological excavations have been carried out, during 1970–76 seasons, at Cape Nome, which has established that more than one cultural phase existed here. 300 pits were excavated to find the archaeological background to the Late Norton and Early Norton phase of civilization in the cape area, which is interpreted as representing the Pre-Birnirk culture, termed as the Cape Nome Phase.[12]

See also

References

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: M. Baker's "Geographic dictionary of Alaska" (1906)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: M. Baker's "Geographic dictionary of Alaska" (1906) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: U.S. Government Printing Office's "Bulletin" (1922)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: U.S. Government Printing Office's "Bulletin" (1922) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: B.K. Emerson's "The Green Schists and Associated Granites and Porphyries of Rhode Island" (1907)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: B.K. Emerson's "The Green Schists and Associated Granites and Porphyries of Rhode Island" (1907) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: A.G. Maddren's "The Koyukuk-Chandalar Region, Alaska" (1913)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: A.G. Maddren's "The Koyukuk-Chandalar Region, Alaska" (1913) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: U.S. Geological Survey's "Reconnaissances in the Cape Nome and Norton Bay regions, Alaska, in 1900" (1901)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: U.S. Geological Survey's "Reconnaissances in the Cape Nome and Norton Bay regions, Alaska, in 1900" (1901)

- 1 2 Circular. The Survey. 1953. pp. 11–. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ "History of Nome". Carrie M. McLain Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 2019-04-13.

- ↑ John R. Bockstoce (1979). The archaeology of Cape Nome, Alaska. UPenn Museum of Archaeology. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-934718-27-1. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ Bulletin (Public domain ed.). U.S. Government Printing Office. 1922. pp. 13–. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Alfred Geddes Maddren (1913). The Koyukuk-Chandalar Region, Alaska. U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 33–. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ Baker 1902, p. 65.

- ↑ Geological Survey (U.S.); Brooks, Alfred Hulse; Collier, Arthur James; Walter Curran Mendenhall; George Burr Richardson (1901). Reconnaissances in the Cape Nome and Norton Bay regions, Alaska, in 1900 (Public domain ed.). Government Printing Office. pp. 50, 59–. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ↑ Emerson, Benjamin Kendall; Perry, Joseph Hartshorn (1907). The Green Schists and Associated Granites and Porphyries of Rhode Island (Public domain ed.). U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 134, 137, 142–. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ↑ "U.S. Decennial Census". Census.gov. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ↑ "Statistics of the Population of Alaska" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 1880.

- ↑ "Report on Population and Resources of Alaska at the Eleventh Census: 1890" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Government Printing Office.

- ↑ John R. Bockstoce (1979). The archaeology of Cape Nome, Alaska. UPenn Museum of Archaeology. pp. 28–. ISBN 978-0-934718-27-1. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

Bibliography

- Baker, Marcus (1902). Geographic Dictionary of Alaska. U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 301–. Retrieved 5 April 2013.