In mathematics, Hausdorff dimension is a measure of roughness, or more specifically, fractal dimension, that was introduced in 1918 by mathematician Felix Hausdorff.[2] For instance, the Hausdorff dimension of a single point is zero, of a line segment is 1, of a square is 2, and of a cube is 3. That is, for sets of points that define a smooth shape or a shape that has a small number of corners—the shapes of traditional geometry and science—the Hausdorff dimension is an integer agreeing with the usual sense of dimension, also known as the topological dimension. However, formulas have also been developed that allow calculation of the dimension of other less simple objects, where, solely on the basis of their properties of scaling and self-similarity, one is led to the conclusion that particular objects—including fractals—have non-integer Hausdorff dimensions. Because of the significant technical advances made by Abram Samoilovitch Besicovitch allowing computation of dimensions for highly irregular or "rough" sets, this dimension is also commonly referred to as the Hausdorff–Besicovitch dimension.

More specifically, the Hausdorff dimension is a dimensional number associated with a metric space, i.e. a set where the distances between all members are defined. The dimension is drawn from the extended real numbers, , as opposed to the more intuitive notion of dimension, which is not associated to general metric spaces, and only takes values in the non-negative integers.

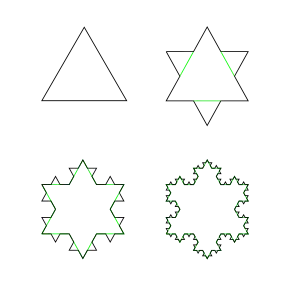

In mathematical terms, the Hausdorff dimension generalizes the notion of the dimension of a real vector space. That is, the Hausdorff dimension of an n-dimensional inner product space equals n. This underlies the earlier statement that the Hausdorff dimension of a point is zero, of a line is one, etc., and that irregular sets can have noninteger Hausdorff dimensions. For instance, the Koch snowflake shown at right is constructed from an equilateral triangle; in each iteration, its component line segments are divided into 3 segments of unit length, the newly created middle segment is used as the base of a new equilateral triangle that points outward, and this base segment is then deleted to leave a final object from the iteration of unit length of 4.[3] That is, after the first iteration, each original line segment has been replaced with N=4, where each self-similar copy is 1/S = 1/3 as long as the original.[1] Stated another way, we have taken an object with Euclidean dimension, D, and reduced its linear scale by 1/3 in each direction, so that its length increases to N=SD.[4] This equation is easily solved for D, yielding the ratio of logarithms (or natural logarithms) appearing in the figures, and giving—in the Koch and other fractal cases—non-integer dimensions for these objects.

The Hausdorff dimension is a successor to the simpler, but usually equivalent, box-counting or Minkowski–Bouligand dimension.

Intuition

The intuitive concept of dimension of a geometric object X is the number of independent parameters one needs to pick out a unique point inside. However, any point specified by two parameters can be instead specified by one, because the cardinality of the real plane is equal to the cardinality of the real line (this can be seen by an argument involving interweaving the digits of two numbers to yield a single number encoding the same information). The example of a space-filling curve shows that one can even map the real line to the real plane surjectively (taking one real number into a pair of real numbers in a way so that all pairs of numbers are covered) and continuously, so that a one-dimensional object completely fills up a higher-dimensional object.

Every space-filling curve hits some points multiple times and does not have a continuous inverse. It is impossible to map two dimensions onto one in a way that is continuous and continuously invertible. The topological dimension, also called Lebesgue covering dimension, explains why. This dimension is the greatest integer n such that in every covering of X by small open balls there is at least one point where n + 1 balls overlap. For example, when one covers a line with short open intervals, some points must be covered twice, giving dimension n = 1.

But topological dimension is a very crude measure of the local size of a space (size near a point). A curve that is almost space-filling can still have topological dimension one, even if it fills up most of the area of a region. A fractal has an integer topological dimension, but in terms of the amount of space it takes up, it behaves like a higher-dimensional space.

The Hausdorff dimension measures the local size of a space taking into account the distance between points, the metric. Consider the number N(r) of balls of radius at most r required to cover X completely. When r is very small, N(r) grows polynomially with 1/r. For a sufficiently well-behaved X, the Hausdorff dimension is the unique number d such that N(r) grows as 1/rd as r approaches zero. More precisely, this defines the box-counting dimension, which equals the Hausdorff dimension when the value d is a critical boundary between growth rates that are insufficient to cover the space, and growth rates that are overabundant.

For shapes that are smooth, or shapes with a small number of corners, the shapes of traditional geometry and science, the Hausdorff dimension is an integer agreeing with the topological dimension. But Benoit Mandelbrot observed that fractals, sets with noninteger Hausdorff dimensions, are found everywhere in nature. He observed that the proper idealization of most rough shapes you see around you is not in terms of smooth idealized shapes, but in terms of fractal idealized shapes:

Clouds are not spheres, mountains are not cones, coastlines are not circles, and bark is not smooth, nor does lightning travel in a straight line.[5]

For fractals that occur in nature, the Hausdorff and box-counting dimension coincide. The packing dimension is yet another similar notion which gives the same value for many shapes, but there are well-documented exceptions where all these dimensions differ.

Formal definition

The formal definition of the Hausdorff dimension is arrived at by defining first the d-dimensional Hausdorff measure, a fractional-dimension analogue of the Lebesgue measure. First, an outer measure is constructed: Let be a metric space. If and ,

where the infimum is taken over all countable covers of . The Hausdorff d-dimensional outer measure is then defined as , and the restriction of the mapping to measurable sets justifies it as a measure, called the -dimensional Hausdorff Measure.[6]

Hausdorff dimension

The Hausdorff dimension of is defined by

This is the same as the supremum of the set of such that the -dimensional Hausdorff measure of is infinite (except that when this latter set of numbers is empty the Hausdorff dimension is zero).

Hausdorff content

The -dimensional unlimited Hausdorff content of is defined by

In other words, has the construction of the Hausdorff measure where the covering sets are allowed to have arbitrarily large sizes (Here, we use the standard convention that ).[7] The Hausdorff measure and the Hausdorff content can both be used to determine the dimension of a set, but if the measure of the set is non-zero, their actual values may disagree.

Examples

- Countable sets have Hausdorff dimension 0.[8]

- The Euclidean space has Hausdorff dimension , and the circle has Hausdorff dimension 1.[8]

- Fractals often are spaces whose Hausdorff dimension strictly exceeds the topological dimension.[5] For example, the Cantor set, a zero-dimensional topological space, is a union of two copies of itself, each copy shrunk by a factor 1/3; hence, it can be shown that its Hausdorff dimension is ln(2)/ln(3) ≈ 0.63.[9] The Sierpinski triangle is a union of three copies of itself, each copy shrunk by a factor of 1/2; this yields a Hausdorff dimension of ln(3)/ln(2) ≈ 1.58.[1] These Hausdorff dimensions are related to the "critical exponent" of the Master theorem for solving recurrence relations in the analysis of algorithms.

- Space-filling curves like the Peano curve have the same Hausdorff dimension as the space they fill.

- The trajectory of Brownian motion in dimension 2 and above is conjectured to be Hausdorff dimension 2.[10]

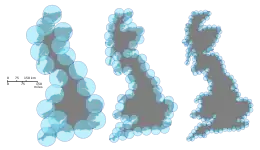

- Lewis Fry Richardson has performed detailed experiments to measure the approximate Hausdorff dimension for various coastlines. His results have varied from 1.02 for the coastline of South Africa to 1.25 for the west coast of Great Britain.[5]

Properties of Hausdorff dimension

Hausdorff dimension and inductive dimension

Let X be an arbitrary separable metric space. There is a topological notion of inductive dimension for X which is defined recursively. It is always an integer (or +∞) and is denoted dimind(X).

Theorem. Suppose X is non-empty. Then

Moreover,

where Y ranges over metric spaces homeomorphic to X. In other words, X and Y have the same underlying set of points and the metric dY of Y is topologically equivalent to dX.

These results were originally established by Edward Szpilrajn (1907–1976), e.g., see Hurewicz and Wallman, Chapter VII.

Hausdorff dimension and Minkowski dimension

The Minkowski dimension is similar to, and at least as large as, the Hausdorff dimension, and they are equal in many situations. However, the set of rational points in [0, 1] has Hausdorff dimension zero and Minkowski dimension one. There are also compact sets for which the Minkowski dimension is strictly larger than the Hausdorff dimension.

Hausdorff dimensions and Frostman measures

If there is a measure μ defined on Borel subsets of a metric space X such that μ(X) > 0 and μ(B(x, r)) ≤ rs holds for some constant s > 0 and for every ball B(x, r) in X, then dimHaus(X) ≥ s. A partial converse is provided by Frostman's lemma.[11]

Behaviour under unions and products

If is a finite or countable union, then

This can be verified directly from the definition.

If X and Y are non-empty metric spaces, then the Hausdorff dimension of their product satisfies[12]

This inequality can be strict. It is possible to find two sets of dimension 0 whose product has dimension 1.[13] In the opposite direction, it is known that when X and Y are Borel subsets of Rn, the Hausdorff dimension of X × Y is bounded from above by the Hausdorff dimension of X plus the upper packing dimension of Y. These facts are discussed in Mattila (1995).

Self-similar sets

Many sets defined by a self-similarity condition have dimensions which can be determined explicitly. Roughly, a set E is self-similar if it is the fixed point of a set-valued transformation ψ, that is ψ(E) = E, although the exact definition is given below.

Theorem. Suppose

are each a contraction mapping on Rn with contraction constant ri < 1. Then there is a unique non-empty compact set A such that

The theorem follows from Stefan Banach's contractive mapping fixed point theorem applied to the complete metric space of non-empty compact subsets of Rn with the Hausdorff distance.[14]

The open set condition

To determine the dimension of the self-similar set A (in certain cases), we need a technical condition called the open set condition (OSC) on the sequence of contractions ψi.

There is an open set V with compact closure, such that

where the sets in union on the left are pairwise disjoint.

The open set condition is a separation condition that ensures the images ψi(V) do not overlap "too much".

Theorem. Suppose the open set condition holds and each ψi is a similitude, that is a composition of an isometry and a dilation around some point. Then the unique fixed point of ψ is a set whose Hausdorff dimension is s where s is the unique solution of[15]

The contraction coefficient of a similitude is the magnitude of the dilation.

In general, a set E which is carried onto itself by a mapping

is self-similar if and only if the intersections satisfy the following condition:

where s is the Hausdorff dimension of E and Hs denotes s-dimensional Hausdorff measure. This is clear in the case of the Sierpinski gasket (the intersections are just points), but is also true more generally:

Theorem. Under the same conditions as the previous theorem, the unique fixed point of ψ is self-similar.

See also

- List of fractals by Hausdorff dimension Examples of deterministic fractals, random and natural fractals.

- Assouad dimension, another variation of fractal dimension that, like Hausdorff dimension, is defined using coverings by balls

- Intrinsic dimension

- Packing dimension

- Fractal dimension

References

- 1 2 3 MacGregor Campbell, 2013, "5.6 Scaling and the Hausdorff Dimension," at Annenberg Learner:MATHematics illuminated, see , accessed 5 March 2015.

- ↑ Gneiting, Tilmann; Ševčíková, Hana; Percival, Donald B. (2012). "Estimators of Fractal Dimension: Assessing the Roughness of Time Series and Spatial Data". Statistical Science. 27 (2): 247–277. arXiv:1101.1444. doi:10.1214/11-STS370. S2CID 88512325.

- ↑ Larry Riddle, 2014, "Classic Iterated Function Systems: Koch Snowflake", Agnes Scott College e-Academy (online), see , accessed 5 March 2015.

- 1 2 Keith Clayton, 1996, "Fractals and the Fractal Dimension," Basic Concepts in Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos (workshop), Society for Chaos Theory in Psychology and the Life Sciences annual meeting, June 28, 1996, Berkeley, California, see , accessed 5 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 Mandelbrot, Benoît (1982). The Fractal Geometry of Nature. Lecture notes in mathematics 1358. W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-1186-9.

- ↑ Briggs, Jimmy; Tyree, Tim (3 December 2016). "Hausdorff Measure" (PDF). University of Washington. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ↑ Farkas, Abel; Fraser, Jonathan (30 July 2015). "On the equality of Hausdorff measure and Hausdorff content". arXiv:1411.0867 [math.MG].

- 1 2 Schleicher, Dierk (June 2007). "Hausdorff Dimension, Its Properties, and Its Surprises". The American Mathematical Monthly. 114 (6): 509–528. arXiv:math/0505099. doi:10.1080/00029890.2007.11920440. ISSN 0002-9890. S2CID 9811750.

- ↑ Falconer, Kenneth (2003). Fractal Geometry: Mathematical Foundations and Applications (2nd ed.). John Wiley and Sons.

- ↑ Morters, Peres (2010). Brownian Motion. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ This Wikipedia article also discusses further useful characterizations of the Hausdorff dimension.

- ↑ Marstrand, J. M. (1954). "The dimension of Cartesian product sets". Proc. Cambridge Philos. Soc. 50 (3): 198–202. Bibcode:1954PCPS...50..198M. doi:10.1017/S0305004100029236. S2CID 122475292.

- ↑ Falconer, Kenneth J. (2003). Fractal geometry. Mathematical foundations and applications. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.

- ↑ Falconer, K. J. (1985). "Theorem 8.3". The Geometry of Fractal Sets. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-25694-1.

- ↑ Hutchinson, John E. (1981). "Fractals and self similarity". Indiana Univ. Math. J. 30 (5): 713–747. doi:10.1512/iumj.1981.30.30055.

Further reading

- Dodson, M. Maurice; Kristensen, Simon (June 12, 2003). "Hausdorff Dimension and Diophantine Approximation". Fractal Geometry and Applications: A Jubilee of Benoît Mandelbrot. Proceedings of Symposia in Pure Mathematics. Vol. 72. pp. 305–347. arXiv:math/0305399. Bibcode:2003math......5399D. doi:10.1090/pspum/072.1/2112110. ISBN 9780821836378. S2CID 119613948.

- Hurewicz, Witold; Wallman, Henry (1948). Dimension Theory. Princeton University Press.

- E. Szpilrajn (1937). "La dimension et la mesure". Fundamenta Mathematicae. 28: 81–9. doi:10.4064/fm-28-1-81-89.

- Marstrand, J. M. (1954). "The dimension of cartesian product sets". Proc. Cambridge Philos. Soc. 50 (3): 198–202. Bibcode:1954PCPS...50..198M. doi:10.1017/S0305004100029236. S2CID 122475292.

- Mattila, Pertti (1995). Geometry of sets and measures in Euclidean spaces. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-65595-8.

- A. S. Besicovitch (1929). "On Linear Sets of Points of Fractional Dimensions". Mathematische Annalen. 101 (1): 161–193. doi:10.1007/BF01454831. S2CID 125368661.

- A. S. Besicovitch; H. D. Ursell (1937). "Sets of Fractional Dimensions". Journal of the London Mathematical Society. 12 (1): 18–25. doi:10.1112/jlms/s1-12.45.18.

Several selections from this volume are reprinted in Edgar, Gerald A. (1993). Classics on fractals. Boston: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-58701-7. See chapters 9,10,11 - F. Hausdorff (March 1919). "Dimension und äußeres Maß" (PDF). Mathematische Annalen. 79 (1–2): 157–179. doi:10.1007/BF01457179. hdl:10338.dmlcz/100363. S2CID 122001234.

- Hutchinson, John E. (1981). "Fractals and self similarity". Indiana Univ. Math. J. 30 (5): 713–747. doi:10.1512/iumj.1981.30.30055.

- Falconer, Kenneth (2003). Fractal Geometry: Mathematical Foundations and Applications (2nd ed.). John Wiley and Sons.

External links

- Hausdorff dimension at Encyclopedia of Mathematics

- Hausdorff measure at Encyclopedia of Mathematics