| Decree of Canopus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Material | Granodiorite |

| Size | 7 feet 4 inches in height |

| Writing | Egyptian hieroglyphs, demotic, and Koine Greek script |

| Created | 238 BC |

| Discovered | 1866 Tanis, Egypt |

| Discovered by | Karl Richard Lepsius |

| Present location | Egyptian Museum, Cairo, Egypt |

The Decree of Canopus is a trilingual inscription in three scripts, which dates from the Ptolemaic period of ancient Egypt. It was written in three writing systems: Egyptian hieroglyphs, demotic, and Koine Greek, on several ancient Egyptian memorial stones, or steles. The inscription is a record of a great assembly of priests held at Canopus, Egypt, on 7 Appellaios (Mac.) = 17 Tybi (Eg.) year 9 of Ptolemy III = Thursday 7 March 238 BC (proleptic Julian calendar). Their decree honoured Pharaoh Ptolemy III Euergetes; Queen Berenice, his wife; and Princess Berenice.[1]

Ancient Copies of the Decree

In 1866, Karl Richard Lepsius discovered at Tanis the first copy of this Decree (this copy was originally known as the 'Şân Stele'). Another copy was found in 1881 by Gaston Maspero at Kom el-Hisn in the western Nile Delta. Later on, some other fragmentary copies were found. In March 2004, while excavating at Bubastis, the German-Egyptian 'Tell Basta Project' archaeologists discovered yet another well preserved copy of the Decree.

Importance for the decipherment of hieroglyphs

This is the second earliest of the series of trilingual inscriptions of the "Rosetta Stone Series", also known as Ptolemaic Decrees. Having a greater number of different hieroglyphs than the Rosetta Stone, the Canopus Stone has proved crucial in deciphering them. There are four such decrees:

- The Decree of Alexandria from 243 BC;

- The Decree of Canopus of Ptolemy III in 238 BC;

- The Decree of Memphis, for Ptolemy IV in 218 BC;

- The Memphis Decree (whose best-known copy is the Rosetta Stone), inscribed for Ptolemy V in 196 BC.

Contents of the inscription

The inscription touches on subjects such as military campaigns, famine relief, Egyptian religion and governmental organization in Ptolemaic Egypt. It mentions the king's donations to the temples, his support for the Apis and Mnevis cults, which enjoyed huge success in the Macedonian – Egyptian world, and the return of divine statues which had been carried off by Cambyses. It extols the king's success in quelling insurgencies of native Egyptians, operations referred to as 'keeping the peace.' It reminds the reader that during a year of low inundation, the government had remitted taxes and imported grain from abroad. It inaugurates a solar calendar with 365¼ days per year (the most accurate in the ancient world). It declares the deceased princess Berenike a goddess and creates a cult for her, with women, men, ceremonies, and special 'bread-cakes'. Lastly it orders the decree to be incised in stone or bronze in both hieroglyphs and Greek, and to be publicly displayed in the temples.[2]

The Decree of Canopus attested the existence of the ancient city of Heracleion, which is now submerged, and has only recently been excavated. The Decree informs, in its Greek version, that a synod of priests was held in the city of Heracleion during the reign of King Ptolemy I.[3]

Calendar reform

The civil Egyptian calendar had 365 days: twelve months of thirty days each and an additional five epagomenal days. According to the reform, the five-day "Opening of the Year" ceremonies would include an additional sixth day every fourth year.[4] The reason given was that the rise of Sothis advances to another day in every 4 years, so that attaching the beginning of the year to the heliacal rising of the star Sirius would keep the calendar synchronized with the seasons.

This Ptolemaic calendar reform failed, but was finally officially implemented in Egypt by Augustus in 26 or 25 BC, now called the Alexandrian calendar,[5] with a sixth epagomenal day occurring for the first time on 29 August 22 BC.[6] Julius Caesar had earlier implemented a 365+1⁄4 day year in Rome in 45 BC as part of the Julian calendar.

Gallery

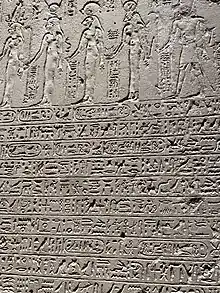

the Decree of Canopus, on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Egypt

the Decree of Canopus, on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Egypt top portion of the Decree of Canopus, on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Egypt

top portion of the Decree of Canopus, on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Egypt middle portion of the Decree of Canopus, on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Egypt

middle portion of the Decree of Canopus, on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Egypt bottom portion of the Decree of Canopus, on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Egypt

bottom portion of the Decree of Canopus, on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Egypt

See also

- Ptolemaic Decrees

- Decree of Memphis, or Raphia Decree, for Ptolemy IV

- Great Mendes Stela, for Ptolemy II

- Rosetta Stone decree, for Ptolemy V

References

- ↑ Robinson Ellis, A Commentary on Catullus, Adamant Media Corporation 2005, ISBN 1-4021-7101-3, p. 295

- ↑ "Egyptian Texts: Canopus Decree". attalus.org. Retrieved 2023-04-27.

- ↑ PDF file Research by Franck Goddio

- ↑ "Egyptian to Julian conversion: Canopic reform analysis". www.instonebrewer.com. Retrieved 2023-04-27.

- ↑ Marshall Clagett, Ancient Egyptian Science: A Source Book, Diane 1989, ISBN 0-87169-214-7, p. 47

- ↑ Chris Bennett, Egyptian Civil Calendar and table note 372

Sources

- Budge. The Rosetta Stone, E.A.Wallace Budge, (Dover Publications), (c) 1929, Dover edition (unabridged), 1989. (softcover, ISBN 0-486-26163-8)

- Pfeiffer, Stefan. Das Dekret von Kanopos (238 v. Chr.). Kommentar und historische Auswertung eines dreisprachigen Synodaldekretes der ägyptischen Priester zu Ehren Ptolemaios' III. und seiner Familie. Munich/Leipzig: K. G. Saur, 2004.

External links

- The Canopus Decree, Hieroglyphic version: full translation by E. A. Wallis Budge (about 1800 words; copied at attalus.org )

- The Canopus Decree, Greek version: full translation at attalus.org )

- Stele of Canopus and the Rosetta Stone