The history of Canada during World War II begins with the German invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939. While the Canadian Armed Forces were eventually active in nearly every theatre of war, most combat was centred in Italy,[1] Northwestern Europe,[2] and the North Atlantic. In all, some 1.1 million Canadians served in the Canadian Army, Royal Canadian Navy, Royal Canadian Air Force, out of a population that as of the 1941 Census had 11,506,655 people, and in forces across the empire, with approximately 42,000 killed and another 55,000 wounded.[3] During the war, Canada was subject to direct attack in the Battle of the St. Lawrence, and in the shelling of a lighthouse at Estevan Point on Vancouver Island, British Columbia.[4]

The financial cost was $21.8 billion between 1939 and 1950.[5] By the end of the war Canada had the world's fourth largest air force,[6] and third largest navy.[7] The Canadian Merchant Navy completed over 25,000 voyages across the Atlantic,[8] 130,000 Allied pilots were trained in Canada in the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. On D-Day, 6 June 1944 the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division landed on "Juno" beach in Normandy, in conjunction with allied forces. The Second World War had significant cultural, political and economic effects on Canada, including the conscription crisis in 1944 which affected unity between francophones and anglophones. The war effort strengthened the Canadian economy and furthered Canada's global position.[9]

Preparations

Though Canada was the oldest Dominion in the British Empire, it was, for the most part, reluctant to enter the war. Canada, with a population somewhere between 11 and 12 million, eventually raised very substantial armed forces. Around 10% of the entire population of Canada joined the army, with only a small portion being conscripted. After the long struggle of the Great Depression of the 1930s, the challenges of the Second World War accelerated Canada's ongoing transformation into a modern urban and industrialized nation.

Canada informally followed the British Ten Year Rule, which reduced defence spending even after Britain abandoned it in 1932. Having suffered from nearly 20 years of neglect, Canada's armed forces were small, poorly equipped, and mostly unprepared for war in 1939. King's government began increasing spending in 1936, but the increase was unpopular. The government had to describe it as primarily for defending Canada, with an overseas war "a secondary responsibility of this country, though possibly one requiring much greater ultimate effort." The Sudeten crisis of 1938 caused annual spending to almost double. Nonetheless, in March 1939 the Permanent Active Militia (or Permanent Force (PF), Canada's full-time army) had only 4,169 officers and men while the Non-Permanent Active Militia (Canada's reserve force) numbered 51,418 at the end of 1938, mostly armed with weapons from 1918. In March 1939 the Royal Canadian Navy had 309 officers and 2967 naval ratings, and the Royal Canadian Air Force had 360 officers and 2797 airmen.[10]: 2–5

Under Secretary of State for External Affairs Oscar D. Skelton stated the government's war policy. Among its highlights:

- Consult with Britain and France, and "equally important, discreet consultation with Washington."

- Prioritize Canadian defence, especially the Pacific coast.

- Possibly aid Newfoundland and the West Indies.

- The RCAF should be the first to serve overseas.

- Canada can "most effective[ly]" serve its allies by providing munitions, raw materials, and food.[10]: 9

King's cabinet approved this policy on 24 August 1939, and in September disapproved of the proposal by the Chiefs of Staff to create two army divisions for overseas service, in part because of cost. His "moderate" war strategy soon demonstrated its national and bilingual support in two elections. When Premier of Quebec Maurice Duplessis called an election on an antiwar platform, Adélard Godbout's Liberals won a majority on 26 October 1939. When the Legislative Assembly of Ontario passed a resolution criticizing the government for not fighting the war "in the vigorous manner the people of Canada desire to see," King dissolved the federal parliament, and at the resulting election on 26 March 1940, his Liberals won the largest majority in history.[10]: 9–11

Outbreak of war

Declaration of war

When the United Kingdom declared war on Germany in August 1914, Canada was a Dominion of the British Empire with full control over only domestic affairs and thus automatically joined the First World War. After the war, the Canadian government wanted to avoid a repeat of the Conscription Crisis of 1917, which had divided the country and French and English Canadians. Stating that "Parliament will decide," Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King avoided participating in the Chanak Crisis in 1922, partly since the Parliament of Canada was not in session.[11]

The 1931 Statute of Westminster gave Canada autonomy in foreign policy. When Britain entered World War II in September 1939, some experts suggested that Canada was still bound by Britain's declaration of war because it had been made in the name of their common monarch, but Prime Minister King again said that "Parliament will decide."[11][10]: 2

In 1936, King had told Parliament, "Our country is being drawn into international situations to a degree that I myself think is alarming."[10]: 2 Both the government and the public remained reluctant to participate in a European war, partly because of the Conscription Crisis of 1917. Both King and Opposition Leader Robert James Manion stated their opposition to conscripting troops for overseas service in March 1939. Nonetheless, King had not changed his view of 1923 that Canada would participate in a war by the Empire whether or not the United States did. By August 1939 his cabinet, including French Canadians, was united for war in a way that it probably would not have been during the Munich Crisis, although both cabinet members and the country based their support in part on expecting that Canada's participation would be "limited."[10]: 5–8

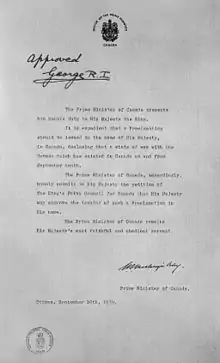

It had been clear that Canada would elect to participate in the war before the invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939. Four days after the United Kingdom had declared war on 3 September 1939, Parliament was called in special session and both King and Manion stated their support for Canada following Britain, but did not declare war immediately, partly to show that Canada was joining out of her own initiative and was not obligated to go to war. Unlike 1914 when war came as a surprise, the government had prepared various measures for price controls, rationing, and censorship, and the War Measures Act of 1914 was re-invoked.[12] After two days of debate, the House of Commons approved an Address in Reply to the Speech from the Throne on 9 September 1939 giving authority to declare war to King's government. A small group of Quebec legislators attempted to amend the bill, and CCF party leader J. S. Woodsworth stated that some of his party opposed it. Woodsworth was the only Member of Parliament to vote against the bill.[13][14] The Senate also passed the bill that day. The Cabinet drafted a proclamation of war that night, which Governor-General Lord Tweedsmuir signed on 10 September.[15] King George VI approved Canada's declaration of war with Germany on Sept. 10.[16] Canada later also declared war on Italy (11 June 1940), Japan (7 December 1941), and other Axis powers, enshrining the principle that the Statute of Westminster conferred those sovereign powers on Canada.

Mobilization and deployment

At the outbreak of war, Canada's commitment to the war in Europe was limited by the government to one division, and one division in reserve for home defence. Nevertheless, the eventual size of the Canadian armed forces greatly exceeded those envisioned in the pre-war period's so-called mobilization "schemes." Over the course of the war, the army enlisted 730,000; the air force 260,000; and the navy 115,000 personnel. In addition, thousands of Canadians served in the Royal Air Force. Approximately half of Canada's army and three quarters of its air force personnel never left the country, compared to the overseas deployment of approximately three-quarters of the forces of Australia, New Zealand, and the United States. By war's end, however, 1.1 million men and women had served in uniform for Canada.[17] The navy grew from only a few ships in 1939 to over 400 ships, including three aircraft carriers and two cruisers. That maritime effort helped keep the shipping lanes open across the Atlantic throughout the war.

In part, this reflected Mackenzie King's policy of "limited liability" and the labour requirements of Canada's industrial war effort, but it also reflected the objective circumstances of the war. With France defeated and occupied, there was no Second World War equivalent of the First World War's Western Front until the invasion of Normandy occurred in June 1944. While Canada sent 348 troops, the manpower requirements of the North Africa and Mediterranean theatres were comparatively small and readily met by British and other British Empire/Commonwealth forces.

While the response to war was initially intended to be limited, resources were mobilized quickly. Convoy HX 1 departed Halifax just six days after the nation declared war, escorted by HMCS St. Laurent and HMCS Saguenay.[18] The 1st Canadian Infantry Division arrived in Britain on 1 January 1940.[19] By 13 June 1940, the 1st Battalion of The Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment was deployed to France in an attempt to secure the southern flank of the British Expeditionary Force in Belgium. By the time the battalion arrived, the British and allies were cut off at Dunkirk, Paris had fallen, and after penetrating 200 km inland, the battalion returned to Brest and then to Britain.

Apart from the Dieppe Raid in August 1942, the frustrated Canadian Army fought no significant engagement in the European theatre of operations until the invasion of Sicily in the summer of 1943. With the Sicily Campaign, the Canadians had the opportunity to enter combat and later were among the first to enter Rome.

Canada was the only country of the Americas to be actively involved in the war prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor.[20]

Canadian support for the war was mobilized through a propaganda campaign, including If Day, a staged Nazi invasion of Winnipeg that generated more than $3 million in war bonds.

Early campaigns

Although it regularly consulted with Canada, Britain was essentially in charge of both countries' war plans during the first nine months of the war. Neither nation seriously planned for Canada's own defence; Canada's training, production, and equipment emphasized combat in Europe. Its primary role was to supply food, raw materials, and to train pilots from throughout the Empire with the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan the British proposed on 26 September 1939, not send hundreds of thousands of troops overseas as it had done in World War I.[21][22]

It is possible that Britain did not want Canada to send troops overseas at all. The Canadian government agreed, because doing so might result in the need for conscription, and it did not want a recurrence of the problem with French Canadians that caused the 1917 crisis. Public opinion did cause King to send the 1st Canadian Infantry Division in late 1939, possibly against British wishes, but it is possible that had the air training proposal arrived ten days earlier no Canadian troops would have left North America that year. Canada fully cooperated with Britain otherwise, devoting 90% of the manpower of the small Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) to the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan;[21][22] a force that had trained 125 pilots annually when the war began now produced 1,460 airmen every four weeks under the plan,[10]: 252 the largest air force training program in history. 131,553 air force personnel, including 49,808 pilots, were trained at airbases in Canada from October 1940 to March 1945.[23] More than half of the BCAT graduates were Canadians who went on to serve with the RCAF and Royal Air Force (RAF). One out of the six RAF Bomber Command groups flying in Europe was Canadian.

In 1937 the two nations had agreed that any Canadian military equipment manufactured in Canada would use British designs. While this reasonably assumed that its troops would presumably always fight with Britain so the two forces should share equipment, it also resulted in Canada being dependent on components from a source across the Atlantic. Canadian manufacturing methods and tooling used American, not British designs, so implementing the plan would have meant complete changes to Canadian factories. Once war began, however, British companies refused Canadians their designs and Britain was uninterested in Canadian military equipment production.[21] (When Canada suggested in early 1940 that its factories could replace British equipment given to the 1st Canadian Division, Britain replied that Canada might provide regimental badges.) While Britain gave Canada priority over the United States for purchases, Canada had very little military production capacity in 1939 and Britain had a shortage of Canadian dollars.[10]: 31, 494 As late as 12 June 1940, King's government and the Canadian Manufacturers' Association asked the British and French governments to end their "small experimental orders" and "make known at the earliest moment their pressing needs of munitions and supplies" since "Canadian plants might be utilized to a far greater extent as a source of supply."[24]

This situation began to change on 24 May 1940, during the Battle for France, when Britain told Canada that it could no longer provide equipment. 48 hours later, Britain asked Canada for equipment. On 28 May, seven Canadian destroyers sailed to the English Channel and left only two French submarines to defend the nation's Atlantic coast. Canada also sent 50 to 60 million rounds of small arms ammunition and 75,000 Ross rifles, leaving itself with a shortage. The air training plan's first graduates were intended to become instructors for future students, but they were sent to Europe immediately because of the danger to Britain. The end of British equipment deliveries threatened the training plan, and King had to ask US President Franklin D. Roosevelt for aircraft and engines by stating that they would help defend North America.[21][10]: 35–36

As the fall of France grew imminent Britain looked to Canada to provide additional troops to strategic locations in North America rapidly, the Atlantic and Caribbean. In addition to the Canadian destroyer already on station from 1939, Canada provided troops from May 1940 to assist in the defence of the West Indies with several companies serving throughout the war in Bermuda, Jamaica, the Bahamas and British Guiana.[10]

Canadian forces played a small role during the Battle of France, with the 1st Canadian Infantry Brigade being deployed to Brest as a part of the second British Expeditionary Force (BEF).[25] The brigade advanced towards Le Mans on 14 June before they withdrew to the United Kingdom from Brest, and Saint-Malo on 18 June.[25] The Royal Canadian Navy assisted with the evacuation of the BEF, the 1st Canadian Division, and additional Allied troops in a series of naval forays known as Operation Cycle and Operation Ariel.[26]

Defence of the United Kingdom

From France's collapse in June 1940 to the German invasion of the USSR in June 1941, Canada supplied Britain with urgently needed food, weapons, and war materials by naval convoys and airlifts, as well as pilots and planes who fought in the Battle of Britain and the Blitz. During the Battle of Britain between 88 and 112 Canadian pilots served in the RAF,[27] most having come to Britain on their own initiative. For political necessity an "all Canadian" squadron, No. 242 Squadron RAF, was formed under the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan at the start of the war and the squadron served in the Battle of France. They were later joined by No. 1 Squadron RCAF in June 1940 during the Battle for Britain and they were in "the thick" of fighting in August. By the end of the battle in October 1940, 23 Canadian pilots had been killed.[28] Squadrons of the RCAF and individual Canadian pilots flying with the British RAF fought with distinction in Spitfire and Hurricane fighters during the Battle of Britain. By 1 January 1943, there were enough RCAF bombers and crews in Britain to form No. 6 Group, one of eight bomber groups within RAF Bomber Command. If the planned German invasion of Britain had taken place in 1941, units of the formation later known as I Canadian Corps were already deployed between the English Channel and London to meet them.

After France's surrender Britain told Canada that a German invasion of North America was not impossible, and that Canadians needed to plan accordingly. From June 1940 Canada viewed defending itself as important as aiding Britain, perhaps slightly more so. Canadian troops were sent to the defence of the colony of Newfoundland, on Canada's east coast, the closest point in North America to Germany. Fearing the loss of a land link to the British Isles, Canada was requested to also occupy Iceland, which it did from June 1940 to the spring of 1941, following the initial British invasion.[10] Canada also produced military equipment using American methods and tooling. Cost was no longer an issue; on 24 June King's government presented the first $1 billion budget in Canadian history. It included $700 million in war expenses compared to $126 million in the 1939–1940 fiscal year; however, the war, caused the overall economy to be the strongest in Canadian history. With opposition support, the National Resources Mobilization Act initiated nationwide conscription across Canada. Hoping to avoid the issue that sparked the 1917 crisis, conscripted Canadians could not be sent to fight overseas unless they volunteered. Nonetheless, many remained adamantly opposed to any form of conscription; when Mayor of Montreal Camilien Houde spoke out against the draft in August 1940, he was arrested and sent to an internment camp.[21][10]: 32–33

The United States government also feared the consequences to North America of a German victory in Europe. Because of the Monroe Doctrine the American military had long considered any foreign attack on Canada as the same as attacking the United States. American isolationists who criticized Roosevelt administration aid to Europe could not criticize helping Canada,[21][29] which a survey of Americans in the summer of 1940 found that 81 per cent supported defending.[30] The isolationist Chicago Tribune advocating a military alliance on 19 June surprised and pleased Canada.[29] Through King, the United States asked the United Kingdom to disperse the Royal Navy around the Empire so that the Germans could not control it. On 16 August 1940, King met with Roosevelt at the border town of Ogdensburg, New York. Through the Ogdensburg Agreement, they agreed to create the Permanent Joint Board on Defence, an organization that would plan joint defence of both countries and would continue to exist after the war. In the fall of 1940 a British defeat seemed so likely the joint board agreed to give the United States command of the Canadian military if Germany won in Europe. By the spring of 1941, as the military situation improved, Canada refused to accept American control of its forces if and when the United States entered the war.[31]

Newfoundland

When war was declared, Britain expected Canada to take responsibility for defending British North America.[10] In 1939, L. E. Emerson was the Commissioner of Defence for Newfoundland.[note 1] Winston Churchill instructed Emerson to cooperate with Canada and comply with a "friendly invasion," as he encouraged Mackenzie King to advise the occupation of Newfoundland by the king as monarch of Canada. By March 1942, Commissioner Emerson had restructured official organizations, such as The Aircraft Detection Corps Newfoundland, and integrated them into Canadian units, like The Canadian Aircraft Identity Corps.

Several Canadian regiments were garrisoned in Newfoundland during the Second World War: the most famous regiment was The Royal Rifles of Canada who were stationed at Cape Spear before being dispatched to British Hong Kong; In July 1941, The Prince Edward Island Highlanders arrived to replace them; In 1941 and 1942, The Lincoln & Welland Regiment was assigned to Gander Airport and then St. John's.

The Canadian Army built a concrete fort at Cape Spear with several large guns to deter German naval raids. Other forts were built overlooking St. John's Harbour; magazines and bunkers were cut into the South Side Hills and torpedo nets were draped across the harbour mouth. Cannons were erected at Bell Island to protect the merchant navy from submarine attacks and guns were mounted at Rigolette to protect Goose Bay.

The British Army mustered two units in Newfoundland for overseas service: The 59th Field Artillery and the 166th Field Artillery. The 59th served in northern Europe, the 166th served in Italy and North Africa. The Royal Newfoundland Regiment was also mustered, but was never deployed overseas. No. 125 (Newfoundland) Squadron R.A.F. served in England and Wales and provided support during D-Day: the squadron was disbanded on 20 November 1945.[32]

All Canadian soldiers assigned to Newfoundland from 1939 to 1945 received a silver clasp to their Canadian Volunteer Service Medal for overseas service. Because Canada, South Africa, New Zealand and Australia had all issued their own volunteer service medals, the Newfoundland government minted its own volunteer service medal in 1978. The Newfoundland Volunteer War Service Medal was awarded only to Newfoundlanders who served overseas in the Commonwealth Forces but had not received a volunteer service medal. The medal is bronze: on its obverse is a crown and a caribou; on its reverse is Britannia and two lions.

Saint Pierre and Miquelon

After the fall of France, the French overseas collectivity of Saint Pierre and Miquelon, located off the coast of Newfoundland, pledged allegiance to Vichy France. The Canadian government considered the possibility that the Axis might use Saint Pierre and Miquelon as a base of operations. The colony's proximity to Canada and Newfoundland could offer German submariners an excellent position to re-supply and coordinate attacks upon Allied convoys. This was helped by the fact that the islands could communicate with the French mainland through wireless communication and transatlantic cables. The governments of Newfoundland and the UK considered an invasion of the islands in consultation with Canada. However, Canada's War Cabinet refused to initiate an action for fear of offending the US. A Free French flotilla landed 230 sailors on the islands on 24 December 1941. Saint Pierre and Miquelon administrator Gilbert de Bournat offered no resistance. A plebiscite on the island later voted overwhelmingly to endorse the Free French administration.

Battle of Hong Kong

In Autumn 1941, the British government accepted an offer by the Canadian Government to send two infantry battalions and a brigade headquarters (1,975 personnel) to reinforce British, Indian, and Hong Kong personnel garrisoned at Hong Kong. It was known as "C Force" and arrived in Hong Kong in mid-November 1941, but did not have all of its equipment. They were initially positioned on the south side of the Island to counter any amphibious landing. On 8 December, following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese began their attack on Hong Kong with a force 4 times bigger than the Allied garrison. Canadian soldiers were called upon to counterattack, and saw their first combat on 11 December. After bitter fighting, allied forces surrendered on 25 December 1941. "C Force" lost 290 personnel during the battle and a further 267 subsequently perished in Japanese prisoner of war camps.

Dieppe Raid

There was pressure from the Canadian government to ensure that Canadian troops were put into action.[33] The Dieppe Raid of 19 August 1942, landed nearly 5,000 soldiers of the inexperienced Second Canadian Division and 1,000 British commandos on the coast of occupied France, in the only major combined forces assault on France prior to the Normandy invasion. While a large number of aircraft flew in support, naval gunfire was deliberately limited to avoid damage to the town and civilian casualties. As a result, the Canadian forces assaulted a heavily defended coast line with no supportive bombardment. Of the 6,086 men who made it ashore, 3,367 (60%) were killed, wounded, or captured.[34] The Royal Air Force failed to lure the Luftwaffe into open battle, and lost 106 aircraft (at least 32 to flak or accidents), compared to 48 lost by the Luftwaffe.[35] The Royal Navy lost 33 landing craft and one destroyer. Two Canadians received the Victoria Cross for actions at Dieppe: Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Merritt of the South Saskatchewan Regiment and Honorary Captain John Foote, military chaplain of the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry.

The lessons learned at Dieppe became the textbook of "what not to do" in amphibious operations, and laid the framework for the later (Operation Torch) landings in North Africa and the Normandy landings in France. Most notably, Dieppe highlighted:

- the need for preliminary artillery support, including aerial bombardment;[36]

- the need for a sustained element of surprise;

- the need for proper intelligence concerning enemy fortifications;

- the avoidance of a direct frontal attack on a defended port city; and,

- the need for proper re-embarkation craft.[37]

The British developed a range of specialist armoured vehicles which allowed their engineers to perform many of their tasks protected by armour, most famously Hobart's Funnies. The major deficiencies in RAF ground support techniques led to the creation of a fully integrated Tactical Air Force to support major ground offensives.[38] Because the treads of most Churchill tanks were caught up in the shingle beaches of Dieppe, the Allies initiated pre-operation environmental intelligence collection, and devised appropriate vehicles to meet the challenges of future landing sites.[39] The raid also challenged the Allies' belief that the seizure of a major port would be essential in the creation of a second front. Their revised view was that the amount of damage sustained by bombardment in order to capture a port, would almost certainly render it useless. As a result, the decision was taken to construct prefabricated "Mulberry" harbours, and tow them to beaches as part of a large-scale invasion.[40]

Aleutian Islands campaign

Shortly after the attack of Pearl Harbor, and the American entry into the war, Japanese troops invaded the Aleutian Islands. RCAF planes flew anti-submarine patrols against the Japanese while on land, Canadian troops were deployed side by side with American troops against the Japanese. Owing to circumstances, Canadians troops were only once sent into combat during the Aleutian campaign during the invasion of the island of Kiska. However, the Japanese had already withdrawn their forces at that point.

European theatre (1943–45)

Italian campaign

While Canadians served at sea, in the air, and in small numbers attached to Allied formations and independently, the Italian campaign was the first full scale combat engagement by full Canadian divisions since World War I. Canadian soldiers went ashore in 1943 in the Allied invasion of Sicily, the subsequent Allied invasion of Italy, and then fought through the long Italian Campaign.[41] During the course of the Allied campaign in Italy, over 25,000 Canadian soldiers became casualties of war.[42]

The 1st Canadian Division and the 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade took part in the Allied invasion of Sicily in Operation Husky, 10 July 1943 and also Operation Baytown, part of the Allied invasion of Italy on 3 September 1943. Canadian participation in the Sicily and Italy campaigns were made possible after the government decided to break up the First Canadian Army, sitting idle in Britain. Public pressure for Canadian troops to begin fighting forced a move before the awaited invasion of northwest Europe.[43]

Fighting continued on the Italian mainland during the long and difficult Italian campaign, until Canadian troops were redeployed to the Western Front in February–March 1945 during Operation Goldflake. By this time the Canadian contribution to the Italian theatre had grown to include I Canadian Corps headquarters, the 1st Division, 5th Canadian (Armoured) Division and an independent armoured brigade. Notable battles in Italy included the Moro River Campaign (4 December 1943 – 4 January 1944), the Battle of Ortona (20–28 December 1943) and the battles to break the Hitler Line, later fighting on the Gothic Line.

Three Victoria Crosses were awarded to Canadian Army troops in Italy: Captain Paul Triquet of the Royal 22e Régiment, Private Smokey Smith of The Seaforth Highlanders of Canada, and Major John Mahoney of The Westminster Regiment (Motor).

Liberation of France

On 6 June 1944, the 3rd Canadian Division landed on Juno Beach in the Normandy landings and sustained heavy casualties in their first hour of attack. By the end of D-Day, the Canadians had penetrated deeper into France than either the British or the American troops at their landing sites, overcoming stronger resistance than the other beachheads except Omaha Beach. In the first month of the Normandy campaign, Canadian, British and Polish troops were opposed by some of the strongest and best trained German troops in the theatre, including the 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler, the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend and the Panzer-Lehr-Division. One in seven Canadian soldiers killed between June 6–11 were murdered after surrendering, in a series of executions that would be coined the Normandy Massacres.[44]

Several costly operations were mounted by the Canadians to fight a path to the pivotal city of Caen and then south towards Falaise, part of the Allied attempt to liberate Paris. By the time the First Canadian Army linked up with U.S. forces, closing the Falaise pocket, the destruction of the German Army in Normandy was nearly complete. Three Victoria Crosses were earned by Canadians in Northwest Europe; Major David Currie of the South Alberta Regiment received the Victoria Cross for his actions at Saint-Lambert, Captain Frederick Tilston of the Essex Scottish and Sergeant Aubrey Cosens of the Queen's Own Rifles of Canada were rewarded for their service in the Rhineland fighting in 1945, the latter posthumously. 50,000 Canadians fought in D-Day.

The Low Countries

One of the most important Canadian contributions was the Battle of the Scheldt, involving II Canadian Corps, under Lieutenant-General Guy Simonds, under command of the First Canadian Army, commanded by General Henry Duncan Graham Crerar. The Corps included the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, 3rd Canadian Infantry Division and 4th Canadian (Armoured) Division. Although nominally a Canadian formation, II Canadian Corps contained the Polish 1st Armoured Division, with the 1st Belgian Infantry Brigade, and the Royal Netherlands Motorized Infantry Brigade. The British 51st Infantry Division was attached to the Corps.

The British had liberated Antwerp, but that city's port could not be used until the Germans were driven from the heavily fortified Scheldt estuary.[45] In several weeks of heavy fighting in the fall of 1944, the Canadians succeeded in defeating the Germans in this region. The Canadians then turned east and played a central role in the liberation of the Netherlands. In 1944–45, the First Canadian Army was responsible for liberating much of the Netherlands from German occupation. Canada lost 7,600 troops in those operations.[46] This day is celebrated on 5 May commemorating the surrender of the German Commander-in-chief Johannes Blaskowitz to Lieutenant-General Charles Foulkes, commanding I Canadian Corps, consisting of the 1st Canadian Infantry Division, 5th Canadian (Armoured) Division and the 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade, together with supporting units. The Corps had returned from fighting on the Italian Front in February 1945 as part of Operation Goldflake.

The arrival of Canadian troops came at a time of crisis for the Netherlands: the "hunger winter." Canadian troops gave their rations to children, and blankets to civilians. Bombers were used to drop food packets to hungry civilians in German-occupied Rotterdam, Amsterdam, and the Hague in "Operation Manna," with permission from Germany if the bombers did not fly above 200 feet.[47]

The royal family of the Netherlands had moved to Ottawa until the Netherlands were liberated, and Princess Margriet was born during this Canadian exile. Princess Juliana of the Netherlands, the only child of then-Queen Wilhelmina and heir to the throne, sought refuge in Canada with her two daughters, Beatrix and Irene, during the war. During Princess Juliana's stay in Canada, preparations were made for the birth of her third child. To ensure the Dutch citizenship of this royal baby, the Canadian Parliament passed a special law declaring Princess Juliana's suite at the Ottawa Civic Hospital "extraterritorial." On 19 January 1943, Princess Margriet was born. The day after Princess Margriet's birth, the Dutch flag was flown on the Peace Tower. That was the only time a foreign flag has waved atop Canada's Parliament Buildings.

In 1945, the people of the Netherlands sent 100,000 handpicked tulip bulbs as a postwar gift for the role played by Canadian soldiers in the liberation of the Netherlands. Those tulips were planted on Parliament Hill and along the Queen Elizabeth Driveway. Princess Juliana was so pleased at the prominence given to the gift that in 1946, she decided to send a personal gift of 20,000 tulip bulbs to show her gratitude for the hospitality received in Ottawa. The gift was part of a lifelong bequest. Since then, tulips have proliferated in Ottawa as a symbol of peace, freedom and international friendship. Every year, Canada's capital receives 10,000 bulbs from the Dutch royal family, celebrated in the Canadian Tulip Festival. In 1995, the Netherlands donated an additional 5,000 bulbs for Parliament Hill, 1,000 for each provincial and territorial capital and 1,000 for Ste. Anne's Hospital in Saint-Anne-de-Bellevue, Quebec, (the only remaining federal hospital in Canada, administered by Veterans Affairs Canada.[46] It is thought that the Netherlands and the Dutch people have had an enduring affection for Canada and Canadians long after the war, lingering into the present day.[47][48]

Naval warfare

Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic was the longest ongoing battle in World War II. Once Britain declared war on Germany, Canada quickly followed, entering the war on 10 September 1939, as they had a vested interest in sustaining Britain.[49]: 56

Canadian security relied on British success in this war, along with maintaining national security, politically speaking, some felt it was Canada's duty to assist her allies. For example, the Canadian prime minister Mackenzie King had been utterly convinced that it was Canada's "Self-evident national duty" to "back Britain."[49]: 38

Once World War II had erupted in 1939, Canada had a small navy. In 1939 Canada had seven warships. Once entering the war, Canada needed a naval reformation in order to keep up with and aid the British. On the outbreak of the war Canada had roughly 3,500 men supporting the RCN. In September 1940 "the RCN grew to 10,000 men."[49]: 134

The Canadian government agencies also played a major role in the patterns of warfare in the Atlantic. The Canadian Navies Division operated a network of naval control of shipping agents in the neutral United States from 1939 to 1941. Those agents managed the shipping movements of British shipping in the United States and also managed the growing United States Navy systems in regards to basic trade movements. Special publications on trade matters were supplied to the United States Navy from Ottawa in 1941, and by the time of Pearl Harbor American port directors were working with Ottawa as a team. Ottawa's job of studying trade movements and keeping track of intelligence was so effective and crucial that they were given the task of controlling shipping west of 40〫and north of the equator from December 1941 to July 1942, along with supplying the USN trade directorate with daily intelligence.[50]

Canada was also given the responsibility of covering two strategically-key points in the Atlantic. The first is known as the "Mid-Atlantic Gap," located off the coast of Greenland. The gap was a very hostile point in the supply line, which was very difficult to take control. With the use of Iceland as a refuelling point and Canada to the west, the gap was narrowed down to 300 nautical miles (560 km). "The Surface gap was closed by the Royal Canadian Navy [in 1943]. The Newfoundland Escort Force started with 5 Canadian corvettes and two British destroyers [manned by Canadian seamen], followed by other Canadian-manned British destroyers when available."[51]

The second task Canada was given was to control the English Channel during Operation Overlord (the Normandy landings). "On the 6th of June, 50 RCN escorts were redeployed from the North Atlantic and Canadian Waters for invasion duties."[49]: 144 Their tasks were to cover the flanks of the invasion to ensure submarine defence of the invasion fleet, also to provide distant patrols of the southern flank of the invasion area, and lastly to prevent submarine flotillas in the channel from gaining reinforcements. That invasion relied on the RCN to cover British and American flanks to ensure a successful landing on the beaches of Normandy.[49]: 144

Canada saw enormous growth during World War II, going from a limited amount of warships to becoming the third largest navy in the world after the Axis powers were defeated and the role they played in aiding the USN in intelligence. Their primary role in protecting merchant ships from North America to Britain was ultimately successful, though that victory was shared with the major Allied powers. Throughout the war Canada had made 25,343 successful escort voyages delivering 164,783,921 tons of cargo.[49]: 56 By the end of the war, German documents state that the Royal Canadian Navy was responsible for the loss of 52 submarines in the Atlantic. In return 59 Canadian merchant ships, and 24 warships were sunk during the battle of the Atlantic.[52]

"Canadians solved the problem of the Atlantic convoys." – British Admiral Sir Percy Noble

Southeast Asia and the Pacific

Canadian naval and special forces participated in various capacities in the Pacific and South-East Asia. The cruisers HMCS Ontario and HMCS Uganda, along with the armed merchant cruiser HMCS Prince Robert were assigned to the British Pacific Fleet. HMCS Uganda was in theatre at the time. HMCS Ontario arrived to support the post-war operations in the Philippines, Hong Kong and Japan. However the Uganda was the only Royal Canadian Navy ship to take an active part against the Japanese while serving with the British Pacific Fleet. Various Canadian special forces also served in Southeast Asia including the "Sea Reconnaissance Unit," a team of navy divers tasked to spearhead assaults across the rivers in Burma.[10][53]

Conditions aboard HMCS Uganda, compared to ships in the United States Navy, strict discipline, and the inability to display a separate Canadian identity, had contributed to poor morale and resentment amongst the crew. In an attempt to remedy that and mindful of the change in Canadian government policy that only volunteers would now serve overseas, the ship's commander, Captain Edmond Rollo Mainguy, invited crew members (before the official date) to register their unwillingness to serve overseas. Of the 907 crew members, 605 did so on 7 May 1945.[54][55]

This decision, which had legal impact, was relayed to Canada and thence to the British government. Reacting to the angry British response, the Canadians agreed to stay on station until replaced. This happened on 27 July 1945, when HMS Argonaut joined the British Pacific Fleet and Uganda departed for Esquimalt arriving on the day of the Japanese surrender.[54]

Attacks in Canadian waters and the mainland

Axis U-boats operated in Canadian and Newfoundland waters throughout the war, sinking many naval and merchant vessels. Two significant attacks took place in 1942 when German U-boats attacked four allied ore carriers at Bell Island, Newfoundland. The carriers SS Saganaga and SS Lord Strathcona were sunk by U-513 on 5 September 1942, while SS Rosecastle and P.L.M 27 were sunk by U-518 on 2 November with the loss of 69 lives. When the submarine fired a torpedo at the loading pier, Bell Island became the only location in North America to be subject to direct attack by German forces in the Second World War. U-boats were also found in the St. Lawrence River; during the night of 14 October 1942, the Newfoundland Railway ferry, SS Caribou was torpedoed by German U-boat U-69 and sunk in the Cabot Strait with the loss of 137 lives. Both sides fought to outsmart each other and decide the fate of the merchant vessels in the Atlantic Ocean. Several U-boat wrecks have been found in Canadian waters, a few as far in as the Churchill River in Labrador.[56] The Canadian mainland was also attacked when the Japanese submarine I-26 shelled the Estevan Point lighthouse on Vancouver Island on 20 June 1942.

Japanese fire balloons were also launched at Canada, some reaching British Columbia and the other western provinces. The Japanese Fu-Go balloon bombs were released during the winter of 1944–45, although no Canadians were actually hurt by the devices. The Japanese Army hoped that, aside from direct blast effects the incendiary bombs would cause fires. Since the balloons had to be launched in the winter, when the jet stream is at its strongest, the snow-covered ground prevented any fires from spreading. Nevertheless, 57 devices were found during the war as far east as Manitoba. Many others were discovered as late as 2014.[57][58]

Germany placed an automated weather station on an unpopulated coast in northern Labrador in 1943, called Weather Station Kurt. It was discovered as German as late as 1977, because it was marked "Canadian" so occasional visitors didn't report it.

Home front

Agriculture, mining, and industry

When the Second World War began, Canada was in the midst of escaping the Great Depression and this placed a lot of importance on the industries and farmers of Canada. Canada was in desperate need of workers. During the war, Canada's industries manufactured war materials and other supplies to all allied countries valuing at almost $10 billion – approximately $100 billion today.[59] With men overseas, women began to have a more prominent role in the workplace. Such stringent wage and price restrictions by the government made workers rights' were not adequately acknowledged at the time. Out of Canada's population of 11.3 million, the total number of workers in war industries was roughly 1 million, and 2 million were employed in agriculture, communications, and food processing.[59]

.jpg.webp)

Wheat was one of Canada's largest sources of produce. Although wheat was extremely important, Canada started to drown in wheat production and James Gardiner admitted that farmers needed to produce other agricultural commodities.[60] After Gardiner's speech, farmers took a different direction and by 1944, Canada had produced 7.4 million hogs. Canada's contribution to the war effort was recognized by nations around the world.[60]

After Gardiner requested farmers to produce less wheat, during the next five years the production of wheat dropped. From 1940 to 1945, the income resulting from selling farm products such as livestock, grains, and field crops saw a dramatic increase because of the growing worth and necessity of those goods in the war effort. And since there was a labour shortage in the farm work force, goods became more expensive. Wheat production in Canada dropped by over 200 million bushels a year between 1939 and 1945, but the total income from Canada's wheat production increased by more than $80 000 000.[61]

The Canadian mining and metals industries also made significant contributions to the war effort, with half of Allied aluminum and ninety per cent of Allied nickel was supplied by Canadian sources during the war. The Canadian company Eldorado Gold Mines Ltd., which produced uranium as a byproduct of gold and radium production using ore from its mine at Port Radium in the Northwest Territories, was recruited by the Canadian government into involvement in the Manhattan Project. In particular, Eldorado's refinery at Port Hope processed ore from both Port Radium and the Belgian Congo to produce much of the uranium used in the Little Boy bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima.

_munitions_factory_(I0051818).tif.jpg.webp)

In 1942, Ottawa registered women between ages 20–24 into service sectors to fill in the roles of those who went to war. In total, around 1,073,000 women were in the workforce.[62] Roles that traditionally belonged to men, like agriculture, airforce, labour, and production, were filled in by women seeking to work for the economy. It was also planned for them to take over the jobs of men in the homefront to encourage them to go to war.[63] Women at the homefront provided for the war effort by donating clothes, food, money to medical organizations.[64] Because women were now working, and men going to war, average family sizes decreased, and children had no parents to care for them. There was still a stigma around women working in industries and urban jobs.[65] In contrast, the government had given 4,000-5,000 women a new responsibility- to regulate the food supplies so that it is preserved nor wasted in accordance with the fluctuating consequences of war and weather, something understood as squarely within the domestic sphere.

Children and youth also experienced significant changes to their lives. The older teenagers also served as farmers and joined into the labour force as most able-bodied men were serving overseas. The Canadian government even lowered the minimum age for obtaining a licence to 14 so that teenagers could legally operate tractors and other vehicles.[66]

Indigenous Canadians played a large role on the Home Front during The Second World War. They donated a large amount of money for patriotic and humanitarian causes. The Indigenous Canadians collected scrap metals, rubber and bones in support of the war effort.[67] More specifically, the Inuit population collected animal bones to secretly ship down south to be used for ammunition. The labour shortages across Canada during World War II provided improved financial conditions for many indigenous families. Those shortages provided more work opportunities at higher wages the indigenous people had previously seen. Despite the influx of indigenous people entering the army and contributing at home, there was also some opposition to the war effort on the part of First Nations, Metis and Inuit Canadians, primarily because of taxes imposed on indigenous peoples by the government and the aftereffects of the previous war haunting the indigenous communities. Furthermore, conscription had a negative impact on the relationship between many of Canada's First Nations, Metis, and Inuit communities and the federal government.[67]

Before the war, Chinese Canadians had often experienced discrimination in Canada and through Canada's immigration system. Nevertheless, Chinese-Canadian contributions to the war effort became the basis for their claim to equal treatment in Canada following the war. Though initially discouraged from enlisting, the victory of Japan in Hong Kong led to renewed calls from the British government for the enlistment of Chinese-Canadians, specifically Chinese ones that could speak English and could help with guerrilla warfare. Chinese Canadians fought with the Canadian armed forces and communities raised funds for the war effort . Vancouver Chinese contributed more per capita than any other group towards Victory Loan Drives. Chinese Canadians joined into different service groups, such as the Red Cross. Many young men volunteered for service overseas, and others worked in research, and war industries. Participation in the war was somewhat controversial within the Chinese-Canadian community because of the racist treatment they had historically endured. However, by 1944, participation in the war effort became the basis for a petition demanding increased acknowledgment of the rights of Chinese-Canadians.[68][69][70]

Approximately 160,000 French-Canadian soldiers served overseas, which comprised 20% of all Canadian servicemen. The majority of those soldiers served in Francophone infantry units such as Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal, Le Régiment de Maisonneuve, Le Régiment de la Chaudière, and the Royal 22e Régiment. However, regardless of King's political manoeuvrings, French-Canadians still experienced discrimination as Canadians—many Anglophones still held the same sentiments towards them as they did in the First World War. Despite the number of French-Canadians who joined the military a plebiscite that was held on 27 April 1942 to decide whether or not Canadian conscription for the Second World War should be enforced. It revealed that Quebec and other Francophone ridings were against it, whereas Anglophone communities were overwhelmingly in favour for conscription. The division and ultimate passing of Bill 80 in favour of conscription worsened relations between Anglophones and Francophones in Canada. Although most French-Canadians were against conscription, the Catholic Church ultimately encouraged participation in the war effort. That both spurred volunteerism early in the war and created some divisions between French-Canadians.[71][72][73]

Items manufactured

At the beginning of the Second World War, Canada did not have an extensive manufacturing industry besides car manufacturing.[74] However, by the end of the war, Canada's wartime motor vehicle production constituted 20% of the combined total production of Canada, the US, and the UK.[10]: 167 The nation had become one of the world's leading automobile manufacturers in the 1920s, owing to the presence of branch-plants of American automakers in Ontario. In 1938, Canada's automotive industry ranked fourth in the world in the output of passenger car and trucks, even though a large part of its productive capacity remained idle because of the Great Depression. During the war, the industry was put to good use, building all manner of war material, and most particularly wheeled vehicles, of which Canada became the second-largest producer, after the United States,during the war. Canada's output of about 800,000 trucks and wheeled vehicles,[75][76] for instance, exceeded the combined total truck production of Germany, Italy, and Japan.[77] Rivals Ford and General Motors of Canada pooled their engineering design teams to produce a standardized vehicle series, amenable to mass production: the Canadian Military Pattern (CMP) truck, which served throughout the British Commonwealth. With a production of some 410,000 units, the CMP trucks accounted for the majority of Canada's total truck output;[75] and approximately half of the British Army's transport requirements were supplied by Canadian manufacturers. The British official History of the Second World War argues that the production of soft-skinned trucks, including the CMP truck class, was Canada's most important contribution to Allied victory.[78]

Canada also produced its own medium tank, the Ram. Though it was unsuitable for combat employment, many were used for training, and the 1st Canadian Armoured Carrier Regiment used modified Rams as armoured personnel carriers in North-West Europe.[79] In addition 1,390 Canadian-built Valentine tanks were shipped to the Soviet Union. Approximately 14,000 aircraft, including Lancaster and Mosquito bombers, were built in Canada. In addition, by the end of 1944, Canadian shipyards had launched naval ships, such as destroyers, frigates, corvettes, and some 345 merchant vessels.

Veterans Guard of Canada

As with the Home Guard, the Veterans Guard of Canada was initially formed in the early days of the Second World War as a defence force in case of an attack on Canadian soil. Composed largely of First World War veterans it included, at its peak, 37 Active and Reserve companies with 451 officers and 9,806 other ranks. Over 17,000 veterans served in the force over the course of the war. Active companies served full-time in Canada as well as overseas, including a General Duty Company attached to Canadian Military Headquarters in London, England, No. 33 Coy. in the Bahamas, No. 34 Coy. in British Guiana and Newfoundland, and a smaller group dispatched to India. The Veterans Guard were involved in a three-day prisoner of war uprising in 1942, known as the Battle of Bowmanville. Along with its home defence role, the Veterans Guard assumed responsibility for guarding internment camps from the Canadian Provost Corps, which helped release younger Canadians for service overseas. The Guards were disbanded in 1947.[80]

Arts and culture

The large casualty count and proximity to the First World War heightened the impact of World War II on cultural production domestically. Following pressure from Canadian artist's groups, the government established new supports for artists in the form of the Canadian War Records by the end of 1942.[81] Photography was a privileged medium, with official war artists even being provided cameras by authorities towards the end of the war.[81] War artists also developed courses to enrich soldiers, with formal exhibitions and competitions of war art arranged.[81] References to indigenous culture and contributions to the war effort were largely erased, with recruitment guidelines for the Royal Canadian Air Force as well as Navy requiring volunteers be white. One notable exception was a portrait by Henry Lamb, "A Redskin in the Royal Canadian Artillery" (1942).[81] In 1999, the soldier was identified and the work renamed to "Trooper Lloyd George More, RCA."[81]

Conscription Crisis of 1944

The political astuteness of Mackenzie King, combined with much greater military sensitivity to Quebec volunteers resulted in a conscription crisis that was minor compared to that of the First World War. French-Canadian volunteers were front and centre, in their own units, throughout the war, highlighted by actions at Dieppe (Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal), Italy (Royal 22e Régiment), the Normandy beaches (Le Régiment de la Chaudière), the thrust into the Netherlands (Le Régiment de Maisonneuve), and in the bombing campaign over Germany (No. 425 Squadron RCAF).

Historiography and memory

Canada deployed trained historians to Canadian Military Headquarters in the United Kingdom during the war and paid much attention to the chronicling of the conflict not only in the words of the official historians of the Army Historical Section but also by art and trained painters. The official history of the Canadian Army was undertaken after the war, with an interim draft published in 1948 and three volumes in the 1950s. That was in comparison to the World War I official history, only one volume of which was completed by 1939 and whose full text was released only after a change in authors some 40 years after the fact. Official histories of the RCAF and RCN in the Second World War were also a long time coming, and the book Arms, Men and Government by Charles Perry Stacey (one of the main contributors to the Army history) was published in the 1980s as an "official" history of the war policies of the Canadian government. The performance of Canadian forces in some battles have remained controversial, such as Hong Kong and Dieppe, and a variety of books have been written on them from various points of view. Serious historiansm mainly scholars, emerged in the years after the Second World War, foremost Terry Copp (a scholar) and Denis Whitaker (a former soldier).[82]

See also

|

Uniformed Services |

British Commonwealth |

Leaders

|

Other

|

Notes

- ↑ The Dominion of Newfoundland did not join Canadian Confederation until 1949 (several years after the end of World War II). From 1907 to 1949, Newfoundland was formally a self-governing dominion within the British Empire. However, from 1934 to 1949, Newfoundland was a dominion in name only since it was directly governed from the United Kingdom after the General Assembly of Newfoundland voted to suspend the constitution in 1934.

References

- ↑ Canadian War Museum "The Italian Campaign" Archived 22 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on: 5 August 2007.

- ↑ Canadian War Museum "Liberating Northwest Europe" Archived 15 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on: 5 August 2007.

- ↑ Humphreys, Edward (2013). Great Canadian Battles: Heroism and Courage Through the Years. Arcturus Publishing. p. 151. ISBN 978-1-78404-098-7. Archived from the original on 13 April 2016.

- ↑ Marc Milner (1999). Canada's Navy: The First Century. University of Toronto Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-8020-4281-1.

- ↑ "World War II". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ↑ Canadian Air Force Journal, Vol. 3, No. 1, "World's Fourth Largest Air Force?" Archived 14 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ World War – Willmott, H.P. et al.; Dorling Kindersley Limited, London, 2004, Page 168 Retrieved on: 17 May 2010.

- ↑ Veterans Affairs Canada "The Historic Contribution of Canada's Merchant Navy" Archived 17 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on: 5 August 2007.

- ↑ Stacey, C. "World War II: Cost and Significance". The Canadian Encyclopedia online (Historica). Revised by N. Hillmer. Retrieved on: 5 August 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Stacey, C. P. (1970). Arms, Men and Government: The War Policies of Canada, 1939 – 1945 (PDF). The Queen's Printer by authority of the Minister of National Defence. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- 1 2 Granatstein, J.L. (12 September 2009). "Going to war? 'Parliament will decide'". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 12 September 2009. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ↑ Bishop, Charles (2 September 1939). "Wide System of Govt. Control and Regulation in Canada Is Anticipated". Ottawa Citizen. p. 4. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- ↑ James Shaver Woodsworth, Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2016-03-29

- ↑ Once Upon a Time, Canadians could be proud of Parliament, Globe and Mail, May 04, 2012. Retrieved 2016-03-29

- ↑ Mears, F. C. (10 September 1939). "War Proclamation Issued after United Parliament Overwhelmingly Backs It". The Montreal Gazette. p. 1. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ↑ Donald Creighton, The Forked Road: Canada 1939-1957, McClelland and Stewart, 1976, p.2.

- ↑ J.L. Granatstein (2016). The Weight of Command: Voices of Canada's Second World War Generals and Those Who Knew Them. UBC Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-7748-3302-8.

- ↑ Byers, A. R., ed. (1986). The Canadians at War 1939–45. Westmount, QC: The Reader's Digest Association. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-88850-145-5.

- ↑ Byers, p. 26

- ↑ Murray, D. R. (May 1974). "Canada's First Diplomatic Missions in Latin America". Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs. 16 (2): 1953–1972. doi:10.2307/174735. JSTOR 174735.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dean, Edgard Packard (October 1940). "Canada's New Defense Program". Foreign Affairs. 19 (1): 222–236. doi:10.2307/20029058. JSTOR 20029058.

- 1 2 Douglas, W. A. B. (Spring 1975). "Why Does Canada Have Armed Forces?". International Journal. 30 (2): 259–283. doi:10.2307/40201224. JSTOR 40201224.

- ↑ "Categories of Air Crew Graduates October 1940 March 1945 – Veterans Affairs Canada". Vac-acc.gc.ca. 11 April 2000. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ↑ "Industry Here Eager to Serve". The Montreal Gazette. 12 June 1940. p. 1. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- 1 2 Forczyk, Robert (2017). Case Red: The Collapse of France. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 364. ISBN 978-1-4728-2444-8.

- ↑ Murfett, Malcolm H. (2008). Naval Warfare 1919-45: An Operational History of the Volatile War at Sea. Taylor & Francis. p. 97. ISBN 9781134048137.

- ↑ "History". 24 June 2014.

- ↑ Bungay, Stephen, The Most Dangerous Enemy: A History of the Battle of Britain Aurum Press Ltd, 2009 ISBN 978-1845134815

- 1 2 Dziuban, Stanley W. (1959). "Chapter 1, Chautauqua to Ogdensburg". Military Relations Between the United States and Canada, 1939-1945. Washington DC: Center of Military History, United States Army. pp. 2–3, 18. LCCN 59-60001. Archived from the original on 7 May 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ↑ "What the U.S.A. Thinks". Life. 29 July 1940. p. 20. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ↑ "1939–1945: A World at War". Canada and the World – a History of Canadian Foreign Policy. Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada, Government of Canada. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- ↑ "Sqn Histories 121-125_P". Rafweb.org. Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ↑ Thompson, Julian. "The Dieppe Raid." BBC History (World Wars in Depth series), 30 March 2011

- ↑ Hamilton 1981, pp. 546–558.

- ↑ Franks 1998, pp. 56–62.

- ↑ Thompson, Julian. "The Dieppe Raid." BBC (World Wars in Depth series), 6 June 2010.

- ↑ Maguire 1963, p. 190.

- ↑ "RAF RAF History Timeline 1942." Archived 6 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine raf.mod.uk, 2012 [last update]. Retrieved: 21 July 2012.

- ↑ Foot, M.R.D. "The Dieppe raid."History Today, August 1992. Retrieved: 29 November 2015.

- ↑ Atkin 1980, p. 274.

- ↑ www.veterans.gc.ca: Canada - Italy 1943-1945. The article contains a chapter Canadian Cemeteries and Memorials in Italy.

- ↑ www.veterans.gc.ca: Canada - Italy 1943-1945: " There were 25,264 Canadian casualties in the fighting, including more than 5,900 who were killed."

- ↑ Bercuson, David J. Maple Leaf against the Axis: Canada's Second World War. Toronto: Stoddart, 1995. p. 152.

- ↑ Margolian, Howard (1998). Conduct unbecoming : the story of the murder of Canadian prisoners of war in Normandy. Toronto [Ont.]: University of Toronto Press. pp. 125–155. ISBN 978-1-4426-7321-2. OCLC 431557826.

- ↑ "The Liberation of the Netherlands, 1944-1945". WarMuseums.ca. Canadian Museum of History.

- 1 2 "Liberation of the Netherlands". Canada at War. 12 April 2007.

- 1 2 Debora Van Brenk (30 April 2010). "Canadian vets, Dutch bond endures". Canoe News.

- ↑ "Why Dutchies Love the Canadians". UnClogged in Amsterdam. 21 June 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sarty, Roger (1998). Canada and the Battle of the Atlantic. Canada: Editions Art Global and the Department of National Defence.

- ↑ Milner, Marc (1990). "The Battle of the Atlantic". Journal of Strategic Studies. 13 (1): 45–66. doi:10.1080/01402399008437400.

- ↑ Van Der Vat, Dan (1988). The Atlantic Campaign. New York: Harper and row. pp. 187.

- ↑ Lane, Tony (1993). "50th Anniversary". Battle of the Atlantic Official Souvenir Booklet. 83 (1).

- ↑ Veterans Affairs (21 February 2014). "The Burma Campaign". Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- 1 2 Chaplin-Thomas, Charmion (10 May 2006). "HMCS Uganda Votes". Maple Leaf. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- ↑ Butler, Malcolm. "The Uganda". CFB Esquimalt Naval & Military Museum. Archived from the original on 15 March 2011. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ↑ "German U-Boat may be at bottom of Labrador river". CBC.

- ↑ Crump, Jennifer (2010). "Chapter 12". Canada Under Attack. Dundurn Press Ltd. pp. 167–177. ISBN 978-1-55488-731-6.

- ↑ Moore, Wayne (10 October 2014). "Bomb blown to "smithereens"". Castanet.net. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- 1 2 Canada, Veterans Affairs (20 February 2019). "Canada's Industries Gear up for War – Historical Sheet – Second World War – History – Veterans Affairs Canada". www.veterans.gc.ca. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- 1 2 "The Farmers' War | Legion Magazine". legionmagazine.com. 28 July 2011. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ↑ Santor, Donald M. (1970). Canadiana Scrapbook: Canadians at War 1939-1945. Prentice-Hall. p. 6.

- ↑ "WarMuseum.ca – Democracy at War – Women and the War on the Home Front – Canada and the War". www.warmuseum.ca. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ↑ "Women in Industry". The Globe and Mail. 26 December 1941.

- ↑ "Invaluable Help Given by Women of Eastern Star". The Hamilton Spectator. 13 December 1941.

- ↑ "Chaloult Says Working Women Reduce Families". The Hamilton Spectator. 15 March 1945.

- ↑ Canada, Veterans Affairs (20 February 2019). "Canadian Youth – Growing up in Wartime – Historical Sheet – Second World War – History – Veterans Affairs Canada". www.veterans.gc.ca. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- 1 2 "Indigenous Peoples and the Second World War | The Canadian Encyclopedia". www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ↑ Canada, National Film Board of, Unwanted Soldiers, retrieved 2 February 2020

- ↑ "Chinese Canadian Veterans of WWII – The Memory Project". www.thememoryproject.com. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ↑ Lee, Carol (1976). "The road to enfranchisement: Chinese and Japanese in British Columbia". BC Studies. 30: 50.

- ↑ "WarMuseum.ca – Democracy at War – Francophone Units". www.warmuseum.ca. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ↑ Bélanger, Claude. "Quebec History". faculty.marianopolis.edu. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ↑ "Is There a Deep Split between French and English Canada? | AHA". www.historians.org. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ↑ Dr. J. L. Granatstein – (2005), Arming the Nation: Canada's Industrial War Effort, 1939-1945 Archived 13 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine – Canadian Council of Chief Executives.

- 1 2 Winnington-Ball, Geoff. "CMP Trucks". www.mapleleafup.net.

- ↑ "General Motors of Canada – US Auto Industry in World War Two".

- ↑ "Peter Shawn Taylor: The trucks that beat Hitler". 19 April 2016.

- ↑ Hall, H. Duncan and Wrigley, C. C. Studies of Overseas Supply, a volume in the War Production Series directed by M. M. Postan, published as part of the History of the Second World War. United Kingdom Civil Series edited by Sir Keith Hancock. Her Majesty's Stationery Office and Longmans, Green and Co., London, 1956, pp. 51–52.

- ↑ Tonner, Mark. The Kangaroo in Canadian Service, Service Publications, 2005. See also The Ram in Canadian Service Vol 1. and Vol 2., same publisher.

- ↑ "Canadian Military History Gateway - Glossary". Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Brandon, Laura (2021). War Art in Canada: A Critical History. Toronto: Art Canada Institute. ISBN 978-1-4871-0271-5.

- ↑ Tim Cook, Clio's Warriors: Canadian Historians and the Writing of the World Wars (UBC Press, 2011).

Bibliography

Official histories

- Stacey, C P. (1948) The Canadian Army, 1939–1945 : An Official Historical Summary Archived 31 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine King's Printer, Ottawa (Downloadable PDF)

- Stacey, C P. (1970) Arms, Men and Governments: The War Policies of Canada, 1939–1945 Archived 5 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine Queen's Printer, Ottawa (Downloadable PDF) ISBN D2-5569

- Stacey, C P. (1955) Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War, Vol I Six Years of War Archived 1 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Queen's Printer, Ottawa (Downloadable PDF)

- Nicholson, G.W.L. (1956) Official history of the Canadian Army in the Second World War, Vol II The Canadians in Italy Archived 31 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Queen's Printer, Ottawa (Downloadable PDF)

- Stacey, C P. (1960) Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War, Vol III The Victory Campaign: The Operations in Northwest Europe, 1944–45 Archived 14 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Queen's Printer, Ottawa (Downloadable PDF)

- Feasby, W.R. (1956) Official History of the Canadian Medical Services, 1939–1945, Vol 1 Organization and Campaigns Archived 12 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine Queen's Printer, Ottawa (Downloadable PDF)

- McAndrew, Bill; Bill Rawling, Michael Whitby (1995) Liberation: The Canadians in Europe Archived 12 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine Art Global (Downloadable PDF) ISBN 2-920718-59-2

Further reading

- Biskupski, M. B. (1999). Canada and the Creation of a Polish Army, 1914-1918. The Polish Review, 44(3), 339–380.

- Bryce, Robert Broughton (2005). Canada and the cost of World War II. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-2938-0.

- Campbell, John Robinson (1984). James Layton Ralston and manpower for the Canadian army (M.A. thesis). Wilfrid Laurier University.

- Chartrand, René; Ronald Volstad (2001). Canadian Forces in World War II. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-302-0.

- Ciment, James D. and Thaddeus Russell, eds. The Home Front Encyclopedia: United States, Britain, and Canada in World Wars I and II (ABC-CLIO, 2006)

- Cook, Tim. Warlords: Borden, Mackenzie King and Canada's World Wars (2012) 472pp online

- Copp, J. T; Richard Nielsen (1995). No price too high: Canadians and the Second World War. McGraw-Hill Ryerson. ISBN 0-07-552713-8.

- Cuff, Robert D., and Jack Lawrence Granatstein. Ties that Bind: Canadian-American Relations in Wartime, from the Great War to the Cold War (1977).

- Granatstein, J.L. Canada's War: The Politics of the Mackenzie King Government, 1939-1945 (2nd ed. 1990)

- Hadley, Michael L (1990). U-Boats Against Canada: German Submarines in Canadian Waters. Mcgill Canada. ISBN 0-7735-0801-5.

- Goddard, Lance (2004). D-Day : Juno Beach, Canada's 24 Hours of Destiny. Dundurn Press. ISBN 1-55002-492-2.

- Johnston, Mac (2008). Corvettes Canada: Convoy Veterans of WWII Tell Their True Stories. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-15429-8.

- Littlewood, David. "Conscription in Britain, New Zealand, Australia and Canada during the Second World War." History Compass 18.4 (2020): e12611. online

- Morton, Desmond (1999). A military history of Canada (4th ed.). Toronto: McClelland and Stewart. ISBN 0-7710-6514-0.

- Stacey, C. P. Arms, Men and Governments: The War Policies of Canada 1939–1945 (1970), the standard scholarly history of WWII policies; online free

- Zuehlke, Mark (2005). Juno Beach: Canada's D-Day Victory – June 6, 1944. Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 1-55365-050-6.

Historiography

- Douglas, W. A. B., and B. Greenhous. “Canada and the Second World War: The State of Clio’s Art.” Military Affairs 42#1 (1978), pp. 24–28, online

- Cook, Tim. Clio's Warriors: Canadian Historians and the Writing of the World Wars (UBC Press, 2011).

- Granatstein, J. L."'What is to be Done?' The Future of Canadian Second World War History" Canadian Military Journal (2011) 11#2. online

External links

- Faces of War at Library and Archives Canada

- The Archives of Ontario Remembers the Home Front Archives of Ontario Second World War online exhibit

- www.canadiansoldiers.com—extensive coverage of the Canadian Army in the Second World War

- WWII.ca Archived 14 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine—Canada and the Second World War

- The Road to Victory a dramatized documentary of the Second World War on CD originally broadcast 8 May 1945, on CBC

- Demonstrated Diversity, Canadian World War II Aid to Russia Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Lieutenant Charles Pearson and the Lincoln and Welland Regiment's WWII Campaign