HMS Calypso | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name | Calypso class |

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | Comus class |

| Succeeded by | None |

| Built | 1883–1884 |

| In commission | 1885–1907 |

| Completed | 2 |

| Scrapped | 2 |

| General characteristics [1] | |

| Type | Screw corvette |

| Displacement | 2,770 tons |

| Length | 235 ft 0 in (71.6 m) pp |

| Beam | 44 ft 6 in (13.6 m) |

| Draught | 19 ft 11 in (6.1 m) |

| Installed power | 4,023 ihp (3,000 kW) |

| Propulsion |

|

| Sail plan | Barque rig |

| Speed | 13.75 kn (25.5 km/h) powered; 14.75 kn (27.3 km/h) forced draught |

| Complement | 293 (later 317) |

| Armament |

|

| Armour | Deck: 1.5 in (38 mm) over engines |

The Calypso class comprised two steam corvettes (later classified as third-class cruisers) of the Royal Navy. Built for distant cruising in the heyday of the British Empire, they served with the fleet until the early twentieth century, when they became training ships. Remnants of both survive, after a fashion; HMS Calliope in the name of the naval reserve unit the ship once served, and HMS Calypso both in the name of a civilian charity and the more corporeal form of the hull, now awash in a cove off Newfoundland.

The class exemplifies the transitional nature of the late Victorian navy. In design, materials, armament, and propulsion the Calypsos show evidence of their wooden sailing antecedents, blended with characteristics of the all-metal mastless steam warships which followed. Their appearance and layout was similar to the "pure" sailing corvettes, with boiler rooms, machinery spaces, ventilators, and a flue added. Of iron and steel construction, they had coppering over timber below the waterline, as did older wooden vessels. Their armament was not in turrets or barbettes, but arranged in a central broadside battery, with the four largest guns on sponsons to give larger arcs of fire. And they had both a powerful steam engine and an extensive rig of sail. They formed the last class of sailing corvettes in the Royal Navy.[1][Note 1]

Design

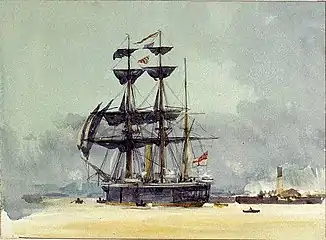

De Maus Collection, Alexander Turnbull Library

Calypso and Calliope comprise Calypso class, a successor to the successful Comus class, all designed by Nathaniel Barnaby. The vessels were screw corvettes or small cruisers, and were among the Royal Navy’s last sailing corvettes. They supplemented an extensive sail rig with a powerful engine.

In profile they resembled older wooden sailing frigates, from bowsprit to stern gallery. The ports in the gallery were false, and there were no quarter galleries.[2] Other differences included a nearly straight stem, a shorter battery, and sponsoned guns on the corners of the battery. Above the decks they had a full suite of masts and spars, standing and running rigging, and square and fore-and-aft sails. The shrouds were not attached to chainplates on the outside of the hull, as in older vessels, but to the inside of the bulwarks. Interposed between the masts and rigging were the ventilators and stack of the steam plant. In plan the ships shows decks common to older sailing cruising vessels, including a poop deck at the rear, the overhang of which sheltered a wheel on the quarterdeck below. The guns were all on the highest continuous deck;[3] the battery was shorter than on wooden vessels with full-length gun decks, as the class carried fewer (although more powerful) guns than corvettes and frigates in the classic age of sail; all guns were carried in the waist of the ship, between the poop and forecastle.

The armament of the class consisted of naval rifles – breechloaders with rifling in their bores to impart a spin and therefore stability to projectiles in flight. The Calypsos differed from the previous Comus class, as they had new 6-inch rifles in place of the 7-inch muzzleloaders and 64-pounders that originally armed the predecessor class, and 5-inch guns in a battery between the 6-inch guns. There were four 6-inch (152.4 mm) breechloaders in sponsons fore and aft on each side, twelve 5-inch (127.0 mm) breechloaders in broadside between the 6-inch guns, and six quick-firing Nordenfelts.[4]

The Calypsos were slightly longer than their predecessors, and displaced 390 tons more.[5] Their engines were of 4,023 i.h.p., over 50% more powerful than those of their nine predecessors, which gave them one more knot of speed.[5] These compound engines could drive the ships at 13¾ knots, or 14¾ knots with forced draught.[6] The hulls of these vessels were of course adapted for the screw driven by their reciprocating steam engines. In common with older vessels, they were coppered to reduce fouling from marine growth, and the copper sheathing was affixed to timber as in wooden ships, but that timber was not structural, but simply encased the metal hull beneath.[7] Royal Navy corvettes had been built of iron since 1867, but the Comus class and the Calypsos were built of steel.[1]

They carried a barque rig of sail on three masts,[Note 2] including a full set of studding sails on fore and mainmasts.[8] This rig enabled them to serve in areas where coaling stations were rare, and to rely on their sails for propulsion. That flexibility made them was well-suited to distant cruising service and trade protection for the British Empire.[6]

The vessels had two complete decks, upper and lower, with poop and forecastle decks. The poop contained cabins for the captain, first lieutenant, and navigating officer, with the double wheel sheltered under its forward end. The forecastle was used for the heads and working space for the cables. Between these was the open quarterdeck in the waist of the ship, on which the battery was located. Under the lower deck were spaces for water, provisions, coal, and magazines for shell and powder. Amidships were the engine and boiler rooms. These were covered by an armoured deck, 1.5 inches (38 mm) thick and approximately 103 feet (31 m) long. This armour was about 3 feet (0.91 m) underneath the lower deck, and the space between could be used for additional coal bunkerage. The machinery spaces were flanked by coal bunkers, affording the machinery and magazines some protection from the sides. The lower deck, above the machinery spaces, was used for berthing of the ship's company; officers aft, warrant and petty officers forward, and ratings amidships, as was traditional. The tops of the coal bunkers, which projected above deck level, could be used for seating on one side of the mess tables, which were arranged fore-and-aft. The living spaces were well-ventilated and an improvement over prior vessels.[9]

Service

Both vessels had relatively short careers with the fleet and in the 1890s were relegated to training and subsidiary duties. They were present at the 1897 Review of the Fleet, held to celebrate Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee.[10]

Calliope

Calliope had achieved fame as the only ship to escape from the 1889 Apia cyclone, and thereafter was known as the "Hurricane Jumper". After fleet service, the vessel became a drill ship on the Tyne in 1907. After the old cruiser was discarded in 1951, the "stone frigate" (shore establishment) operating there was given the name of HMS Calliope.[11]

Calypso

Calypso had a less eventful and shorter naval career than Calliope, but spent more time at sea. As part of the sail training squadron, Calypso cruised in home waters, the North Sea, and the Arctic and Atlantic oceans. In 1902, after that service ended, the ship was sent to the colony of Newfoundland, and served there as a stationary training vessel for the Newfoundland Royal Naval Reserve before and during the First World War. In 1922 the vessel was declared surplus and sold out of the service, and thereafter used as a storage hulk in Lewisporte. The Calypso Foundation, a local charity engaged in training the developmentally disabled, was named after the old training ship.[12] The ship's hull was towed away to a coastal bay and burned out. It is still there, awash in the waters of the Atlantic Ocean.[13][Note 3]

Table of vessels

| Ship | Laid down | Builder | Engine-builder | Launched | Completed | Disposition | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calypso | 1 September 1881 | Chatham Dockyard | J. & G. Rennie | 7 June 1883 | October 1885 | RNR training ship 1902 | Sold 1922, hull still extant |

| Calliope | 1 October 1881 | Portsmouth Dockyard | J. & G. Rennie | 24 July 1884 | 25 January 1887 | RNR training ship 1907 | Sold for breaking 1951 |

Notes

- ↑ The term "corvette" was reintroduced for the Flower and Castle classes of the Second World War.

- ↑ While it has been stated the class had barque rigs, Paine (2000), vol. 799, p. 29, and some images show that, at times they may have been ship rigged, as other drawings and photographs show yards and square sails on the mizzenmast. Archibald (1970), p. 49; J.S. Virtue & Co., lithograph of HMS "Calliope", 3rd Class Cruiser Archived 8 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine; and images linked above at See also, and below.

- ↑ The hull lies in Jobs Cove, off Burnt Bay on the north coast of Newfoundland. An image is here (the hull on the left is that of Calypso), and a search of YouTube will yield amateur footage of the hull.

References

- 1 2 3 Winfield (2004), p. 273

- ↑ Osbon (1963), p. 195.

- ↑ Archibald (1971), pp. 39–42.

- ↑ Osbon (1963), pp. 207–08.

- 1 2 Archibald (1971), p. 49.

- 1 2 Naval Historical Center, HMS Calliope (1884-1951).

- ↑ Lyon (1980), pp. 35–36.

- ↑ Harland, John H. (1985), Seamanship in the Age of Sail, p. 172. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis. ISBN 0-87021-955-3.

- ↑ Osbon (1963), pp. 195–98.

- ↑ "SHIPS NEARLY ALL NEW; Only Four of the 21 Battleships in the Jubilee Display of 1887" (PDF). The New York Times. 27 June 1897. p. 2. Retrieved 15 December 2008.

- ↑ HMS Calliope (Gateshead) Archived 14 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Training Centres, Royal Naval Reserve; History of HMS Calliope Archived 25 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine, News, HMS Calliope (Gateshead), Royal Naval Reserve.

- ↑ Extension Service, Memorial University of Newfoundland (1978), Calypso (video), beginning at 53 seconds into 18-minute video.

- ↑ Lewisporte, Memorial University of Newfoundland, Division of Extension Services, Decks Awash, Vo. 15, No. 3 (May–June 1986), republished by CanadaGenWeb.org. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

Principal sources

- Archibald, E.H.H. (1971). The Metal Fighting Ship in the Royal Navy 1860-1970. Ray Woodward (ill.). New York: Arco Publishing Co. ISBN 0-668-02509-3.

- Brassey, T.A. (1896). The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin and Co.

- Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969]. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Rev. ed.). London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-281-8.

- Lyon, David (1980). Steam, Steel and Torpedoes. Ipswich: W.S. Cowell, Ltd. for HM Stationery Office. p. 39. ISBN 0-11-290318-5.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)

- Osbon, G. A. (1963). "Passing of the steam and sail corvette: the Comus and Calliope classes". Mariner's Mirror. London: Society for Nautical Research. 49: 193–208. doi:10.1080/00253359.1963.10657732. ISSN 0025-3359.

- Paine, Lincoln P. (2000). Warships of the World to 1900. New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-98414-9.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help).

Photographs

- Black and white drawing, port bow 1/4 view, under full sail including stunsails.

- Photograph c. 1910 (sic: vessel is shown in condition prior to 1902 modifications), starboard broadside view, sails set on fore and main, yards on mizzen, jibs set.

- Photograph, port broadside view, no sails set, yards on mizzen.

- Photographs showing Calypso/Briton and personnel in Newfoundland.