The Callier effect is the variation in contrast of images produced by a photographic film with different manners of illumination. It should not be confused with the variation in sharpness which also is due differences partial coherence.

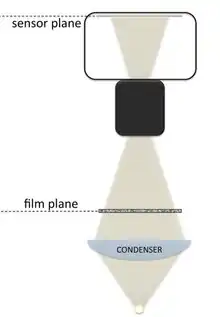

The directed bright-field (see Fig. 1) has extremely strong directional characteristics by means of a point source and an optical system (condenser); in this case, each point of the photographic film receives light from only one direction.

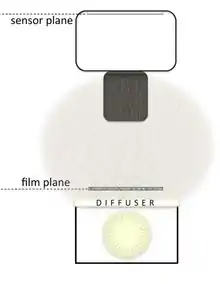

On the other hand, in a diffused bright-field setup (see Fig. 2) the illumination of the film is provided through a translucent slab (diffuser), and each point of the film receives light from a wide range of directions.

The collimation of the illumination plays a fundamental role in contrast of the image impressed on a film.[1]

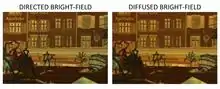

In case of high scattering fraction, the attenuance provided by the image particles changes considerably with the degree of collimation of the illumination. In Figure 3 the same silver-based film is reproduced in directed and diffused bright-field setups. The global contrast also changes: the contrast on the left is much stronger than that on the right.

In the absence of scattering, the attenuance provided by the emulsion is independent of the collimation of the illumination; a dense point absorbs a big portion of light and a less dense point absorbs a smaller portion, irrespective of the directional characteristics of the incident light. In Figure 4 are reported the images of a dye-based film acquired in directed and diffused bright-field setups; the global contrast of the two images is about the same.

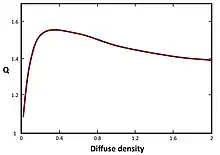

The ratio between the attenuances provided by a specific point of a photographic film, which were measured in directed (Ddir) and diffused (Ddif) bright-fields, is termed the Callier Q factor:

The Callier Q factor is always equal to or greater than unity; its trend versus the diffusely measured density Ddif is depicted in Figure 5 for a typical silver-based film.[2]

These variations (for example with a condenser or a diffuser enlarger) were observed over a long period of time,[3] and they became known as ‘Callier effect’.

The correct optical explanation of the Callier effect had to wait until the 1978 papers of Chavel and Loewenthal.[4]

References

- ↑ C. Tuttle. 1926. "The relationship between diffuse and specular density." J. Opt. Soc. Am. 12, 6 (1926), 559–565.

- ↑ J. G. Streiffert. 1947. "Callier Q of various motion picture emulsions." J. Soc. Mot. Pict. Engrs. 49, 6 (December 1947), 506–522.

- ↑ A. Callier. 1909. "Absorption and scatter of light by photographic negatives." J. Phot. 33 (1909).

- ↑ P. Chavel, S. Lowenthal. 1978. "Noise and coherence in optical image processing. I. The Callier effect and its influence on image contrast." JOSA, Vol. 68, Issue 5, pp. 559–568