| Bui Dam | |

|---|---|

Dam under construction in 2011 | |

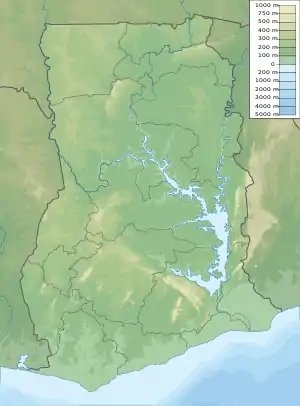

Location of Bui Dam in Ghana | |

| Country | Ghana |

| Location | On the border of the Savannah Region and the Bono Region[1] |

| Coordinates | 8°16′42″N 2°14′9″W / 8.27833°N 2.23583°W |

| Status | Operational |

| Construction began | Preparatory: January 2008 Main dam: December 2009 |

| Opening date | 2013 |

| Construction cost | US$622 million |

| Owner(s) | Bui Power Authority |

| Dam and spillways | |

| Type of dam | Gravity, roller-compacted concrete |

| Impounds | Black Volta River |

| Height (foundation) | 108 m (354 ft) [2] |

| Height (thalweg) | 90 m (300 ft) |

| Length | 492.5 m (1,616 ft) [2] |

| Elevation at crest | 185 m (607 ft) [2] |

| Width (crest) | 7 m (23 ft) [2] |

| Dam volume | 1,000,000 m3 (35,000,000 cu ft) |

| Spillway type | Emergency, five gate-controlled |

| Spillway capacity | 10,450 m3/s (369,000 cu ft/s)[2] |

| Reservoir | |

| Creates | Bui Reservoir |

| Total capacity | 12,570,000,000 m3 (10,190,000 acre⋅ft) [2] |

| Active capacity | 7,720,000,000 m3 (6,260,000 acre⋅ft) [2] |

| Surface area | Minimum level: 288 km2 (111 sq mi) Maximum level: 444 km2 (171 sq mi) [3] |

| Maximum length | 40 km (25 mi) avg. |

| Maximum water depth | 88 m (289 ft)[3] |

| Normal elevation | Minimum level: 167 m (548 ft) Maximum level: 183 m (600 ft) [2] |

| Power Station | |

| Commission date | 2013 |

| Turbines | 3 x 133 MW (178,000 hp) Francis turbines |

| Installed capacity | 400 MW (540,000 hp) |

| Website www | |

The Bui Dam is a 400-megawatt (540,000 hp) hydroelectric project in Ghana. It is built on the Black Volta river at the Bui Gorge, at the southern end of Bui National Park. The project was a collaboration between the government of Ghana and Sino Hydro, a Chinese construction company. Construction on the main dam began in December 2009. Its first generator was commissioned on 3 May 2013,[4] and the dam was inaugurated in December of the same year.[5]

Bui is the second largest hydroelectric generating plant in the country after the Akosombo Dam. The reservoir flooded about 20% of the Bui National Park and impacted the habitats for the rare black hippopotamus as well as a large number of wildlife species. It required the resettlement of 1,216 people,[6] and affected many more.

History

The Bui hydro-electric dam had first been envisaged in 1925 by the British-Australian geologist and naturalist Albert Ernest Kitson when he visited the Bui Gorge. The dam had been on the drawing board since the 1960s, when Ghana's largest dam, the Akosombo Dam, was built further downstream on the Volta River. By 1978 planning for the Bui Dam was advanced with support from Australia and the World Bank. However, four military coups stalled the plans. At the time Ghana began to be plagued by energy rationing, which has persisted since then. In 1992, the project was revived and a first feasibility study was conducted by the French firm Coyne et Bellier.[7]

In 1997 a team of students from Aberdeen University carried out ecological investigations in the area to be flooded by the reservoir.[8] The Ghanaian environmental journalist Mike Anane,[9] who was included in UNEP’s Global 500 Roll of Honour for 1998, called the dam an "environmental disaster" and a "text book example of wasted taxpayer money".[10] In his article he quoted the investigation team, but apparently somewhat exaggerated the environmental impact of the dam. The leader of the investigation team, the zoologist Daniel Bennett, clarified that "the opinions (Anane) attributes to our team are unfair and misleading". He continued to say that "Contrary to Mr Anane's claims, we are unaware of any globally endangered species in Bui National Park, nor did we claim that the dam would destroy the spawning runs of fish."[11] Although Daniel Bennett always maintained a neutral stance towards the construction of the dam, in April 2001 the government of Ghana banned him from doing further research on the ecology of the Bui National Park. The government stated that the issue was "very sensitive" and Bennett's "presence in the National Park was no longer in the national interest". One of the journalist who criticized the government for banning Bennett was Mike Anane.[12]

In 1999 the Volta River Authority, the country's power utility, signed an agreement with the US firms Halliburton and Brown and Root to build the dam without issuing a competitive bid.[7] In December 2000 President Jerry Rawlings, who had ruled the country for the two previous decades, did not contest in elections (as per the constitution) and his party lost to the opposition led by John Kufuor. In October 2001 the new government shelved the dam project. According to Charles Wereko-Brobby, then President of the Volta River Authority, Bui Dam was not considered the least–cost option and could not meet "immediate" energy needs. Instead gas-powered thermal power plants were to be built, producing electricity at what was said to be half the cost of Bui. Furthermore, a severe drought in 1998 exacerbated the energy crisis due to low water levels in Akosombo Dam. As a consequence, the government wanted to reduce its dependence on hydropower at the time.[13]

However, in 2002 the project was revived. An international call for tender was issued, but only a single company submitted a bid and the tender was cancelled. In 2005 the Chinese company Sinohydro submitted an unsolicited bid for the dam together with funding from the Chinese Exim Bank. The government accepted the bid and the Ministry of Energy signed contracts for an environmental impact assessment in December 2005, as well as for an updated feasibility study in October 2007. The government created the Bui Power Authority in August 2007 to oversee the construction and operation of the project and the associated resettlement. Responsibility for the dam was thus transferred from the Volta River Authority, which until then had been responsible for the development and operation of all power projects in Ghana.[7] Coyne et Bellier is the consulting engineer for the dam.[14]

Field investigations for the dam began in October 2007. In January 2008 preparatory construction began and in May 2008 the first people were resettled. In December 2008 the river was diverted and a year later construction on the main part of the dam began. The filling of the reservoir began in June 2011.[15] Unit 3 was connected to the grid on 3 May 2013; Units 2 and 1 were commissioned by the end of November 2013.[4] The dam and power station were inaugurated in December 2013 by President John Mahama.[5]

Design

The Bui Dam is a gravity roller-compacted concrete-type with a height of 108 metres (354 ft) above foundation and 90 metres (300 ft) above the riverbed. The crest of the dam is 492 metres (1,614 ft) meters long and sits at an elevation of 185 metres (607 ft) above sea level (ASL). The main dam's structural volume is 1 million cubic metres (35×106 cu ft). Southwest of the dam two saddle (or auxiliary) dams maintain pool levels and prevent spillage into other areas of the basin. The first and closest to the main dam is Saddle Dam 1. It is 500 metres (1,600 ft) southwest of the main dam and is a rock-fill embankment dam. The dam rises 37 metres (121 ft) above ground level and has a crest length of 300 m (984 ft). 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) southwest of the main dam is Saddle Dam 2. This dam is a zoned earth-fill type with a height of 7 metres (23 ft) ASL and a crest length of 580 m (1,903 ft). Both saddle dams have a crest elevation of 187 metres (614 ft) ASL.[3]

The dam's spillway near the right bank consists of five radial gates, each 15 metres (49 ft) wide. The spillway sits at an elevation of 169 metres (554 ft) and has a maximum discharge of 10,450 cubic metres per second (369,000 cu ft/s) which correlates to a 1-in-10,000 year flood. The dam's outlet works consist of a single outlet on the right bank converted from one of the diversion tunnels.[3]

Reservoir

The reservoir that the main and saddle dams create will have a maximum capacity of 12,570 million cubic metres (10,190,000 acre⋅ft) of which 7,720 million cubic metres (6,260,000 acre⋅ft) is useful for power generation and irrigation. The reservoir's maximum operating level will be 185 metres (607 ft) ASL and the minimum 167 metres (548 ft) ASL. At the maximum level, the reservoir will have a surface area of 440 square kilometres (170 sq mi) while at the minimum it will be 288 square kilometres (111 sq mi). The reservoir's volume at minimum level is 6,600 million cubic metres (5,400,000 acre⋅ft). The average length of the reservoir will be 40 kilometres (25 mi) with an average depth of 29 metres (95 ft) and a maximum 88 metres (289 ft).[3]

Bui Hydropower Plant

Just downstream of the dam on the left bank is the dam's powerhouse. The intake at the reservoir feeds water through three penstocks to the three separate 133 MW Francis turbine-generators. Each turbine-generator has a step-up transformer to increase the voltage to transmission level. A fourth unit, with a penstock on the spillway, will provide four megawatts for station service and black start power, and will provide minimum flow to maintain river levels if the main units should be shut down. The power station will have an installed capacity of 400 megawatts and an estimated average annual generation of 980 gigawatt-hours (3,500 TJ). The power station's switchyard is located 300 metres (980 ft) downstream. Four 161 kV transmission lines connect the substation to the Ghana grid.[2][3]

Benefits

The Bui hydropower plant will increase the installed electricity generation capacity in Ghana by 22%, up from 1920 MW in 2008 to 2360 MW.[16] Together with three thermal power plants that are being developed at the same time, it will contribute to alleviate power shortages that are common in Ghana. Like any hydropower plants, the project avoids greenhouse gas emissions that would have occurred if thermal power plants had been built instead. An additional expected benefit is the irrigation of high-yield crops on 30,000 hectares of fertile land in an "Economic Free Zone".[17] The current status of the irrigation project is unclear.

Cost and financing

The total project costs are estimated to be US$622 million. It is being financed by the government of Ghana's own resources (US$60m) and two credits by the China Exim Bank: a concessional loan of US$270 million at 2% interest and a commercial loan of US$292 million. Both loans have a grace period of five years and an amortization period of 20 years. The proceeds of 30,000 tons per year of Ghanaian cocoa exports to China, which are placed in an escrow account at the Exim Bank, serve as collateral for the loan. Once the dam becomes operational, 85% of the proceeds of electricity sales from the hydropower plant will go to the escrow account. If not all the proceeds are needed to service the loan, the remainder reverts to the government of Ghana.[16]

Environmental and social impact

An Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) for the dam was completed in January 2007 by the US consulting firm Environmental Resources Management (ERM).[3] During its preparation hearings were held in Accra and in five localities near the project area, such as Bamboi. However, no hearings were conducted in the project area itself. Once completed, an independent panel appointed by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) of Ghana reviewed the ESIA. The latter was revised in the important aspects, including the following: "compensation" had to be provided for the inundated area of Bui National Park, a "rescue plan" for the hippos was required and it had to be specified how resettlement would be carried out. When the EPA issued the environmental permit for the dam, it required the Bui Power Authority to present within 18 months an Environmental Management Plan based on the revised ESIA. Construction and resettlement began in 2008, but no environmental management plan had been submitted as of July 2010.[18]

Environmental impact

The Bui National Park will be significantly affected by the Bui Dam. 21% of the park will be submerged. This will affect the only two populations of black hippopotamus in Ghana, whose population is estimated at between 250 and 350 in the park.[8] It is unclear if hippos can be relocated and if there is any suitable habitat near the area to be inundated. Even if there were such a "safe haven", it is not clear if the country's game and wildlife department has the means to rescue the animals.[19] The Environmental and Social Impact Assessment states that hippos will be vulnerable to hunting during the filling period of the reservoir. It also claims that they would ultimately "benefit from the increased area of littoral habitat provided by the reservoir".[3]

The dam could also have other serious environmental impacts, such as changing the flow regime of the river which could harm downstream habitats. A survey by the University of Aberdeen has revealed that the Black Volta River abounds with 46 species of fish from 17 families.[8] None of these species is endangered. Nevertheless, these fish communities could be severely impacted by changes to water temperature, turbidity and the blocking of their migration. Waterborne disease could also occur. Schistosomiasis in particular could become established in the reservoir, with severe health risks for local people.[3][19]

Social impact

The Bui dam project requires the forced relocation of 1,216 people, of which 217 have been resettled as of June 2010.[6] In order not to slow down the construction of the dam, the Bui Power Authority has opted for a quick resettlement process. It neglected the recommendations of a study, the "Resettlement Planning Framework", that it had contracted itself. In theory, all affected people are expected to be moved to a new locality called Bui City. However, as of 2010 the city does not exist and there is not even a schedule for its construction. Instead, the first 217 relocated people have been moved to a temporary settlement called Gyama Resettlement Township, which has dilapidated infrastructure. Fishers were resettled on dry land and lost their livelihoods. Although the study had recommended to establish an independent body to monitor the resettlement, no such body has been set up.[20]

See also

References

- ↑ Bui Power Authority:Frequently Asked Questions Archived July 24, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved on May 7, 2011

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Bui Power Authority:Bui Hydroelectric Project:Project Features Archived July 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved on May 7, 2011

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Environmental Resources Management (ERM):Environmental and Social Impact Assessment of the Bui Hydropower Project Archived 2012-03-08 at the Wayback Machine, Final Report, January 2007, retrieved on May 7, 2011, posted on the website of the Regional Dialogue on large hydraulic infrastructures in the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)

- 1 2 http://www.modernghana.com/news/462096/1/president-mahama-inaugurates-the-bui-hydro-electri.html President Mahama Inaugurates the Bui Hydroelectricity Project retrieved 2013 June 5

- 1 2 "Ghana: Bui Dam Comes Alive - Ghana Energy Problems Now Over". All Africa. 20 December 2014. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- 1 2 Bui Power Authority:Background of the Bui Resettlement Archived July 24, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved on May 7, 2011

- 1 2 3 Oliver Hensengerth:Interaction of Chinese Institutions with Host Governments in Dam Construction:The Bui dam in Ghana Archived October 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, German Development Institute, Discussion Paper 3/2011, p. 9-13, retrieved on May 7, 2011 (full version not available on-line)

- 1 2 3 Bennett, D. and B. Basuglo.D. 1998. Final Report of the Aberdeen University Black Volta Expedition 1997. Viper Press, Aberdeen, Scotland. ISBN 978-0-9526632-3-2

- ↑ Global 500 Forum:Adult Award Winner in 1998: Mike Anane Archived July 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved on May 9, 2011

- ↑ Anane, Mike. "Courting Megadisaster: Bui Dam May Cause Havoc". United Nations Environment Programme. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ↑ Daniel Bennett, Aberdeen University Black Volta Project, letter to newspaper editor re. articles about Bui Dam, 8 November 1999, retrieved on May 9, 2011

- ↑ Anane, Mike. "British Researcher Thrown Out of Ghana, May 8, 2001". International Rivers. Archived from the original on 11 September 2009. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- ↑ "Africa: Other Projects". International Rivers Network. Archived from the original on 2011-08-12. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ↑ "Project Participants". Bui Power Authority. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ↑ Bui Power Authority:Project Milestones and Completion Schedule Archived July 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved on May 7, 2011

- 1 2 Oliver Hensengerth:Interaction of Chinese Institutions with Host Governments in Dam Construction:The Bui dam in Ghana Archived October 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, German Development Institute, Discussion Paper 3/2011, p. 37f., retrieved on May 7, 2011 (full version not available on-line)

- ↑ Bui Power Authority:Bui Hydroelectric Project:Bui Irrigation Project Archived March 23, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved on May 7, 2011

- ↑ Oliver Hensengerth:Interaction of Chinese Institutions with Host Governments in Dam Construction:The Bui dam in Ghana, German Development Institute, Discussion Paper 3/2011, p. 22-24, retrieved on May 7, 2011 (full version not available on-line)

- 1 2 "Ghana: A dam at the cost of forests". World Rainforest Movement. January 2006. Archived from the original on 18 May 2011. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ↑ Oliver Hensengerth:Interaction of Chinese Institutions with Host Governments in Dam Construction:The Bui dam in Ghana Archived October 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, German Development Institute, Discussion Paper 3/2011, p. 27-33 and p. 43, retrieved on May 7, 2011 (full version not available on-line)