British anti-invasion preparations of 1803–05 were the military and civilian responses in the United Kingdom to Napoleon's planned invasion of the United Kingdom. They included mobilization of the population on a scale not previously attempted in Britain, with a combined military force of over 615,000 in December 1803.[1] Much of the southern English coast was fortified, with numerous emplacements and forts built to repel the feared French landing. However, Napoleon never attempted his planned invasion and so the preparations were never put to the test.

Background

In the aftermath of the French Revolution of 1789 Britain and France were at war almost continuously from 1793 to 1802, and then from 1803 to 1815, interrupted only by the brief Peace of Amiens of 1802–3 and Napoleon's first exile at Elba in 1814–15. In late 1797, Napoleon said to the French Directory that:

[France] must destroy the English monarchy, or expect itself to be destroyed by these intriguing and enterprising islanders...Let us concentrate all our efforts on the navy and annihilate England. That done, Europe is at our feet.[2]

However Napoleon decided against invading for the time being and instead unsuccessfully attacked British interests in Egypt. In March 1802 the two countries signed the Treaty of Amiens, which brought to an end nearly nine years of war. However both the British Prime Minister Henry Addington and Napoleon viewed the peace as temporary, and so it was, with Britain declaring war on France on 18 May 1803.[3] William Pitt replaced Addington as Prime Minister on 10 May 1804.

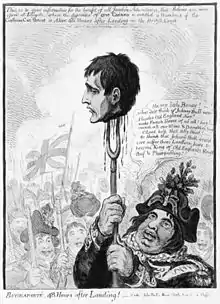

In 1803 Napoleon turned his attention to invading England once more, saying: "All my thoughts are directed towards England. I want only for a favourable wind to plant the Imperial Eagle on the Tower of London".[4] Napoleon now planned an invasion on a bigger scale than 1798 and 1801, and built a new armada for the effort.[5] He assembled the Grande Armée of over 100,000 troops at Boulogne.

British armed forces

Regular Army

Addington's government had kept the Regular army at 132,000 men during the Amiens interlude, with 18,000 in Ireland and 50,000 in Great Britain (the rest serving abroad).[6]

Army of Reserve

In 1803, 50 of the Army's 93 regiments created a second battalion. These battalions became known as the Army of Reserve. In order to bring these units to full strength, 50,000 recruits were raised by ballot within one year of the creation of the form. However, each recruit was only liable to serve in Great Britain. These Reserve soldiers could volunteer as Regular soldiers, and consequently receive money.[7] After 9 months recruiting, fewer than 3,000 of the 42,000 men were balloted men.[8] Within one month of recruiting, it had enlisted 22,500 men. By the end of 1803, it was short of the required 50,000 by 15,000; so the government stopped recruiting for it.[9]

Militia

The Militia was a territorial-based infantry to be used only for home defence and was not a standing army. It was to be raised by ballot. The government in December 1802, fearing war, held a Militia ballot. The ballot was run by churchwardens and overseers of the poor in each parish. A list of men aged between eighteen and forty-five, with many exceptions (such as seamen and Thames watermen), was posted on the front of the church door. However, if a man found himself on the list he could get out of serving by paying a fine or by getting another man to fill his place.[10] Four months after the ballot, and a week into the war, the Militia was filled to 80% of the 51,000 required.[9]

Volunteers

The British government had no choice—in view of Napoleon's avowed determination to invade the United Kingdom—but to rely on the patriotism of the general populace through a volunteer movement.[11] The volunteers' function, as laid down in July 1803 by the Commander-in-Chief of the Forces, Prince Frederick, Duke of York, was to conduct guerrilla warfare against the French occupying forces. It was intended that they would operate in small bodies to confuse, harass, instill panic and wear out the French army. They were never to get deeply engaged with French troops and were to retire to safety when pressed. Local knowledge was to be used as much as possible and they were also expected to cut off French pillaging detachments.[12] In anticipation to criticisms that arming the people was potentially dangerous to the gentry, the Secretary at War in Addington's government (Charles Yorke) said on 18 July 1803 in introducing a Bill for amending the Defence of the Realm Act (the Levy en Masse Act 1803, 43 Geo. 3 c. 96):

I say, that in these times, it is better to run the hazard even of the people making a bad use of their arms, than that they should be actually left in a state of entire ignorance of the use of them. For my own part, I can safely aver, that I cannot see any real danger which is likely to accrue to the internal peace of the Country, when I consider the present dispositions and feelings of the people.[13]

William Pitt, in response, agreed:

I am sure there is not an heart that palpitates in a British bosom that will not rouse for the common cause, and cordially join for the defence of the country. ... That there was a time, Sir, when it would have been dangerous to entrust arms with a great portion of the people of this country, I have strong reasons to know, because it must be in the recollection of every man that incendiaries were at work amongst them; and so successful in the promulgation of revolutionary doctrines, as to have disposed them to exert any means, however desperate, which they thought could be successful, in subverting the Government and Constitution. But that time is now past; and, I trust, those who have been so grosly deluded have seen their error. At least I am convinced, that if any such there still remain, the portion is so small, that if armed and dispersed in the same ranks with their loyal fellow subjects, they would be converted by their example; and, like them, rejoice in the blessings of our happy constitution; like them glory to live under its auspices, or die in its defence.[14]

Even the prominent anti-war MP Charles James Fox supported the Bill:

This is the first measure which I could...come down to support, being a measure for the defence of the country...the mass of the country; acting, not in single regiments, but as a great mass of armed citizens, fighting for the preservation of their country, their families, and every thing that is dear to them in life...an armed mass of the country, who are bound by every feeling and by every tie to defend that country to the last drop of their blood, before they will give way to him and his invading forces.[14]

During 1803 the government's call for volunteers to resist an invasion was met with a massive response. However the government was unprepared for the numbers of volunteers, as within a few weeks 280,000 men had volunteered. On 18 August Addington issued a circular discouraging new volunteers "in any county where the effective members of those corps, including the yeomanry, shall exceed the amount of six times the militia".[15] This had little effect since by the first week of September there were 350,000 volunteers.[16] At least half of the volunteers of the summer and autumn of 1803 were not equipped with their own weapon. When the government tried to issue them with pikes this was met with contempt and attacked by the Opposition leader William Windham.[17]

The second half of 1803 marked the height of the invasion scare.[18][19][20][21][22] When the King reviewed 27,000 volunteers in Hyde Park, London on 26 and 28 October 1803, 500,000 people were estimated to have turned out on each of the two days to witness the event. The Chief Constable of Bramfield (John Carrington) travelled from Hertfordshire to see it, saying: "I never saw such a sight all my days".[19] These were the best-attended of reviews of volunteers which between 1797 and 1805 "were often of daily occurrence".[23]

In 1804 returns to Parliament recorded a total of 480,000 volunteers in uniform. In addition there were the regular forces and the militia, which meant that nearly one-in-five able-bodied men were in uniform.[24] The Speaker, addressing the King at the prorogation of Parliament on 13 August 1803, said "the whole Nation has risen up in Arms".[25] Addington called the volunteer movement on 4 September 1803 "an insurrection of loyalty".[26] The response to the call to arms to resist invasion in these years has impressed some historians: "If some dissentient voices were heard in 1797–8 when the aftermath of the Revolution still lingered in the land, there was increased enthusiasm in the patriotism of 1801, and burning ardour coupled with absolute unanimity in that of 1803–5".[27]

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy kept a constant blockade of French harbours from Toulon to the Texel, just outside artillery range, waiting for a French ship to sail close enough to be attacked.[28] Rear-Admiral of the United Kingdom Admiral Cornwallis had a fleet off Brest and Commander-in-Chief, North Sea, Admiral Keith possessed a fleet between the Downs and Selsey Bill.[20] A further line of British ships lay close to the English coast to intercept any French ships that broke through the blockade.[20] The French were unwilling to venture out of their ports and so in the two years only nine flotilla ships had been captured or sunk by the Royal Navy.[29] During the end of December 1803 a violent storm blew Cornwallis's fleet from Brest and it had to stay in Torbay, giving the French fleet two days opportunity to invade. Upon hearing this Addington gave orders to prepare for an imminent invasion, but the French never used this opportunity.[30]

First Lord of the Admiralty Lord St. Vincent is said to have told the House of Lords: "I do not say the French cannot come, I only say they cannot come by sea".[31][32] This saying is also, with rather more probability, attributed to Admiral Lord Keith, in command in the Downs, who attended a debate in the House of Lords when fears were expressed as to the French tunnelling under the Channel or sending a fleet of hot-air balloons.

A volunteer force called the Sea Fencibles had been formed in 1793; they manned small armed boats, watch and signal towers, and fixed and floating batteries along the coasts.[33]

Fortifications

In July 1803, the Duke of York argued for the construction of field fortifications as soon as possible because "the Erection of such Works must be immediate with a view to their probable utility", placing them at "Points where a Landing threatens the most important interests of the Country".[34] In August he requested from Addington further funds for such fortifications, who eventually consented. The Duke of York's priorities were the building of considerable fortifications at the Western Heights looking over the port of Dover and then the construction of Martello towers along the Kent and Sussex coasts.[35]

Martello towers

Across the coast of Kent and Sussex the government constructed a series of well-fortified towers, known as Martello towers, between 1805 and 1808. In September 1804, Pitt's government ordered General Sir William Twiss to scout the south-east coast of England for possible sites for Martello towers, to be used as artillery emplacements. Twiss earmarked eighty-eight appropriate sites between Seaford and Eastwear Bay. Twiss also headed the team that designed the Martello towers.[36] Twiss's plan was adopted in October at a defence conference in Rochester attended by Pitt, Lord Camden, the Duke of York, Lord Chatham, Major General Sir Robert Brownrigg, Lieutenant Colonel John Brown and Twiss.[37] Eventually seventy-four towers were built, with two (Eastbourne and Dymchurch) being considerably larger with eleven guns and housing 350 soldiers. These became known as Grand Redoubts.[37] A second line of twenty-nine towers, from Clacton-on-Sea to Slaughden near Aldeburgh, was constructed by 1812, including a redoubt at Harwich. Forty were built in Ireland.[38]

Royal Military Canal

During the summer of 1804, Lieutenant Colonel Brown was sent to examine the coast to discover if flooding of Romney Marsh would be viable in case of invasion. Brown thought it would not be and believed security would be improved by the excavation of "a cut from Shorncliffe battery, passing in front of Hythe under Lympne heights to West Hythe...being everywhere within musket shot of the heights".[39] Brown then advocated an extension of the water barrier: "...cutting off Romney Marsh from the county, opening a short and easy communication between Kent and Sussex but, above all, rendering unnecessary the doubtful and destructive measure of laying so large a portion of the country waste by inundation".[39] This became known as the Royal Military Canal, with construction starting in 1805 and completion in 1810.

Western Heights

General Twiss recommended a fortress at Dover, with work beginning in 1804. The Western Heights at Dover consisted of three parts: the Drop Redoubt, the Citadel and the Grand Shaft.[40] The Drop Redoubt was a detached fort close to the steep cliffs, surrounded by ditches and intended for soldiers to go out and attack French infantry, built between 1804 and 1808. The Citadel was a larger fort surrounded by ditches and was still unfinished when war with France ended in 1815. The Grand Shaft was a barracks containing sixty officers and 1300 NCOs and soldiers, begun in 1806 and completed in 1809.[40]

Telegraphs

In order for the government to better communicate with the coast in case of invasion, a system of telegraphs was constructed. In January 1796, a telegraph line from the Admiralty in London to Deal, Kent had been built. In December 1796 another telegraph line was constructed between the Admiralty and Portsmouth. In May 1806 a telegraph line from Beacon Hill on the Portsmouth line to Plymouth was built. A subsequent telegraph line was built between the Admiralty and Great Yarmouth, thus telegraphs covered the south-east, south-west and East Anglia.[41] Before, messages between Portsmouth and London had taken several hours (two days for Plymouth) to reach their destination but now communications between London and Portsmouth took only fifteen minutes. Between London and Hythe it was eleven minutes.[41]

Contingency plans

The King made contingency plans in the event of a French landing, with a courtier writing on 13 November 1803: "The King is really prepared to take the field in case of attack, his beds are ready and he can move at half an hour's warning".[42] Another courtier wrote:

The king certainly has his camp equipage and accoutrements quite ready for joining the army if the enemy should land, and is quite keen on the subject and angry if any suggests that the attempt may not be made. ... God forbid he should have the fate of Harold.[43]

The King wrote to his friend Bishop Hurd from Windsor on 30 November 1803:

We are here in daily expectation that Bonaparte will attempt his threatened invasion; the chances against his success seem so many that it is wonderful he persists in it. I own I place that thorough dependence on Divine Providence that I cannot help thinking the usurper is encouraged to make the trial that the ill-success may put an end to his wicked purposes. Should his troops effect a landing, I shall certainly put myself at the head of my troops and my other armed subjects to repel them. But as it is impossible to foresee the events of such a conflict, should the enemy approach too near to Windsor, I shall think it right the Queen and my daughters should cross the Severn, and send them to your Episcopal Palace at Worcester; by this hint I do not the least mean they shall be any inconvenience to you, and shall send a proper servant and furniture for their accommodation. Should this event arise, I certainly would rather have what I value most in life remain, during the conflict, in your diocese and under your roof than in any other place in the island.[23]

The government's contingency plans laid down that the King would go to Chelmsford if the French landed in Essex, or to Dartford if they landed in Kent, along with the Prime Minister and the Home Secretary. Lord Cornwallis would be in command of the reserve army. The Royal Arsenal artillery and stores and the Ordnance Board's powder magazines in Purfleet, would be put on the Grand Junction canal to the new ordnance depot at Weedon, Northamptonshire. Soldiers would be paid in gold instead of paper money. The Bank of England books would be sent to the Tower of London and its treasure would be entrusted to Sir Brook Watson, the Commissary General, who would transport it in thirty wagons (guarded by a relay of twelve Volunteer escorts) across the Midlands to join the King at Worcester Cathedral. The Stock Exchange would close and the Privy Council would take charge in London. The press would be forbidden from printing troop movements and official government communiqués would be distributed. If London fell to the French, the King and his ministers would retreat to the Midlands and "use the final mainstays of sovereignty – treasure and arms – to keep up the final struggle".[43][44]

Legacy

By the 1 September 1805, Napoleon's invasion camps were empty due to the Grande Armée marching against the Austrians. The Battle of Trafalgar, on 21 October, relieved British fears of invasion as Admiral Nelson destroyed the combined French-Spanish fleet.[45] However, the threat of invasion remained so long as Britain was at war with France. At Tilsit in July 1807, Napoleon and the Russian Tsar Alexander I agreed to combine the navies of Europe against Britain. The British responded with a pre-emptive attack on the Danish fleet at Battle of Copenhagen, and they also made sure the French never secured the Portuguese fleet.[46] Captain Edward Pelham Brenton in his Naval History of Great Britain noted that after Trafalgar "another French navy, as if by magic sprang forth from the forests to the seashore, manned by a maritime conscription exactly similar in principle to that edict by which the trees were appropriated to the building of ships".[47] The First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Melville, noted after the war that given time Napoleon would "have sent forth such powerful fleets that our navy must eventually have been destroyed, since we could never have kept pace with him in building ships nor equipped numbers sufficient to cope with the tremendous power he could have brought against us".[47]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Charles John Fedorak, Henry Addington, Prime Minister, 1801-1804. Peace, War and Parliamentary Politics (Akron, Ohio: The University of Akron Press, 2002), p. 165.

- ↑ H. F. B Wheeler and A. M. Broadley, Napoleon and the Invasion of England. The Story of the Great Terror (Nonsuch, 2007), p. 7.

- ↑ Peter A. Lloyd, The French Are Coming! The Invasion Scare 1803–05 (Spellmount Publishers Ltd, 1992), p. 8.

- ↑ Wheeler and Broadley, p. 9.

- ↑ Frank McLynn, Invasion. From the Armada to Hitler. 1588–1945 (London: Routledge, 1987), p. 98.

- ↑ Lloyd, pp. 119-20.

- ↑ Lloyd, p. 121.

- ↑ Lloyd, p. 123.

- 1 2 Lloyd, p. 126.

- ↑ Lloyd, pp. 121-22.

- ↑ Linda Colley, Britons. Forging the Nation, 1707–1837 (Yale University Press, 2005), p. 284.

- ↑ Admiral Sir Herbert W. Richmond, The Invasion of Britain. An Account of Plans, Attempts & Counter-Measures from 1586 to 1918 (Methuen, 1941), p. 54.

- ↑ The Times (19 July 1803), p. 1.

- 1 2 The Times (19 July 1803), p. 3.

- ↑ Norman Longmate, Island Fortress. The Defence of Great Britain 1603–1945 (Pimlico, 2001), pp. 285-6.

- ↑ Longmate, p. 286.

- ↑ Longmate, pp. 286-7.

- ↑ Wheeler and Broadley, p. 10.

- 1 2 Colley, p. 225.

- 1 2 3 McLynn, p. 100.

- ↑ Longmate, p. 284.

- ↑ Wendy Hinde, George Canning (Purnell Book Services, 1973), pp. 118-9.

- 1 2 Wheeler and Broadley, p. 14.

- ↑ Alexandra Franklin and Mark Philp, Napoleon and the Invasion of Britain (The Bodleian Library, 2003), p. 13.

- ↑ The Times (13 August 1803), p. 2.

- ↑ Philip Ziegler, Addington. A Life of Henry Addington, First Viscount Sidmouth (Collins, 1965), p. 200.

- ↑ Wheeler and Broadley, p. 13.

- ↑ Lloyd, pp. 55-6.

- ↑ Lloyd, p. 66.

- ↑ Fedorak, p. 167.

- ↑ Longmate, p. 267.

- ↑ Lloyd, p. 197.

- ↑ "Sea Fencibles, 1798-1810".

- ↑ Fedorak, pp. 167-68.

- ↑ Fedorak, p. 168.

- ↑ Lloyd, p. 166.

- 1 2 Lloyd, p. 167.

- ↑ Longmate, p. 278.

- 1 2 Lloyd, p. 159.

- 1 2 Longmate, p. 279.

- 1 2 Longmate, p. 269.

- ↑ John Brooke, King George III (Panther, 1974), p. 597.

- 1 2 Lloyd, p. 93.

- ↑ Brooke, p. 598.

- ↑ Correlli Barnett, Britain and Her Army. A Military, Political and Social History of the British Army 1509–1970 (Cassell, 2000), p. 252.

- ↑ Richard Glover, Britain at Bay. Defence against Bonaparte, 1803-14 (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1973), pp. 17-18.

- 1 2 Glover, p. 19.

References

- Correlli Barnett, Britain and Her Army. A Military, Political and Social History of the British Army 1509–1970 (Cassell, 2000).

- John Brooke, King George III (Panther, 1974).

- Linda Colley, Britons. Forging the Nation, 1707–1837 (Yale University Press, 2005).

- J. E. Cookson, The British Armed Nation, 1793–1815 (Clarendon Press, 1997).

- Charles John Fedorak, Henry Addington, Prime Minister, 1801-1804. Peace, War and Parliamentary Politics (Akron, Ohio: The University of Akron Press, 2002).

- Alexandra Franklin and Mark Philp, Napoleon and the Invasion of Britain (The Bodleian Library, 2003).

- Austin Gee, The British Volunteer Movement, 1794–1815 (Clarendon Press, 2003).

- Richard Glover, Britain at Bay. Defence against Bonaparte, 1803-14 (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1973).

- Wendy Hinde, George Canning (Purnell Book Services, 1973).

- Peter A. Lloyd, The French Are Coming! The Invasion Scare 1803–05 (Spellmount Publishers Ltd, 1992)

- Norman Longmate, Island Fortress. The Defence of Great Britain 1603–1945 (Pimlico, 2001).

- Frank McLynn, Invasion. From the Armada to Hitler. 1588–1945 (London: Routledge, 1987).

- Mark Philp, Resisting Napoleon: The British Response to the Threat of Invasion, 1797–1815 (Ashgate, 2006).

- Admiral Sir Herbert W. Richmond, The Invasion of Britain. An Account of Plans, Attempts & Counter-Measures from 1586 to 1918 (Methuen, 1941).

- H. F. B Wheeler and A. M. Broadley, Napoleon and the Invasion of England. The Story of the Great Terror [1908] (Nonsuch, 2007).

- Philip Ziegler, Addington. A Life of Henry Addington, First Viscount Sidmouth (Collins, 1965).