| Andromeda | |

|---|---|

Princess of Aethiopia | |

Perseus freeing Andromeda after killing Cetus, 1st century AD fresco from the Casa Dei Dioscuri, Pompeii | |

| Personal information | |

| Born | |

| Parents | Cepheus and Cassiopeia |

| Consort | Perseus |

| Offspring | Perses, Heleus, Alcaeus, Sthenelus, Electryon, Mestor, Gorgophone |

In Greek mythology, Andromeda (/ænˈdrɒmɪdə/; Ancient Greek: Ἀνδρομέδα, romanized: Androméda or Ἀνδρομέδη, Andromédē) is the daughter of Cepheus, the king of Aethiopia, and his wife, Cassiopeia. When Cassiopeia boasts that she (or Andromeda) is more beautiful than the Nereids, Poseidon sends the sea monster Cetus to ravage the coast of Aethiopia as divine punishment. Queen Cassiopeia understands that chaining Andromeda to a rock as a sacrifice is what will appease Poseidon. Perseus finds her as he is coming back from his quest to decapitate Medusa, and brings her back to Greece to marry her and let her reign as his queen. With the head of Medusa he turns Cetus to stone to stop it from terrorizing the coast any longer.

As a subject, Andromeda has been popular in art since classical times; rescued by a Greek hero, Andromeda's narration is considered the forerunner to the "princess and dragon" motif. From the Renaissance, interest revived in the original story, typically as derived from Ovid's Metamorphoses. The story has appeared many times in such diverse media as plays, poetry, novels, operas, classical and popular music, film, and paintings. A significant part of the northern sky contains several constellations named after the story's figures; in particular, the constellation Andromeda is named after her.

The Andromeda tradition, from classical times onwards, has incorporated elements of other stories, including Saint George and the Dragon, introducing a horse for the hero, and the tale of Pegasus, Bellerophon's winged horse.[1] Ludovico Ariosto's epic poem Orlando Furioso, which tells a similar story, has introduced further confusion.[2] The tradition has been criticized for depicting the princess of Aethiopia as white; few artists have chosen to portray her as dark-skinned, despite Ovid's account of her.[3] Others have noted that Perseus's liberation of Andromeda was a popular choice of subject among male artists, reinforcing a narrative of male superiority with its powerful male hero and its submissive female in bondage.[4][5]

Etymology

The name Andromeda is from the Greek Ἀνδρομέδα, Androméda, perhaps meaning 'mindful of her husband'. The name is from the noun ἀνήρ, ἀνδρός, anēr, andrós meaning 'man', and a verb, whether μεδεσθαι, medesthai, 'to be mindful of', μέδω, mēdein, 'to protect, rule over', or μήδομαι, mēdomai, 'to deliberate, contrive, decide', all related to μήδεια, mēdeia, 'plans, cunning', the likely origin of the name of Medea, the sorceress.[6]

Classical mythology

Central story

In Greek mythology, Andromeda is the daughter of Cepheus and Cassiopeia, king and queen of ancient Aethiopia. Her mother Cassiopeia foolishly boasts that she is more beautiful than the Nereids,[7] a display of hubris by a human that is unacceptable to the gods. To punish the queen for her arrogance, Poseidon floods the Ethiopian coast and sends a sea monster named Cetus to ravage the kingdom's inhabitants. In desperation, King Cepheus consults the oracle of Ammon, who announces that no respite can be found until the king sacrifices his daughter, Andromeda, to the monster. She is thus stripped naked and chained to a rock in Jaffa by the sea to await her death. Perseus is just then flying near the coast of Ethiopia on his winged sandals or on Pegasus the winged horse, having slain the Gorgon Medusa and carrying her severed head, which instantly turns to stone any who look at it. Upon seeing Andromeda bound to the rock, Perseus falls in love with her, and he secures Cepheus' promise of her hand in marriage if he can save her. Perseus kills the monster with the Medusa's head, saving Andromeda. Preparations are then made for their marriage, in spite of her having been previously promised to her uncle, Phineus. At the wedding, a quarrel between the rivals ends when Perseus shows Medusa's head to Phineus and his allies, turning them to stone.[8][9][10]

Andromeda follows her husband to his native island of Serifos, where he rescues his mother, Danaë from her unwanted wedding to the King of Seriphos. .[11] They next go to Argos, where Perseus is the rightful heir to the throne. However, after accidentally killing his grandfather Acrisius, the king of Argos, Perseus chooses to become king of neighboring Tiryns instead.[12] The mythographer Apollodorus states that Perseus and Andromeda have six sons: Perses, Alcaeus, Heleus, Mestor, Sthenelus, Electryon, and a daughter, Gorgophone. Their descendants rule Mycenae from Electryon down to Eurystheus, after whom Atreus attains the kingdom. The Greek hero Heracles is also a descendant, as his mother Alcmene is the daughter of Electryon.[13]

According to the Catasterismi, Andromeda is placed in the sky by Athena as the constellation Andromeda, in a pose with her limbs outstretched, similar to when she was chained to the rock, in commemoration of Perseus' bravery in fighting the sea monster.[14]

In classical art

The myth of Andromeda was represented in the art of ancient Greece and of Rome in media including red-figure pottery such as pelike jars,[15] frescoes,[16] and mosaics.[17] Depictions range from straightforward representations of scenes from the myth, such as of Andromeda being tied up for sacrifice, to more ambiguous portrayals with different events depicted in the same painting, as at the Roman villa in Boscotrecase, where Perseus is shown twice, space standing in for time.[16] Favoured scenes changed with time: until the 4th century BC, Perseus was shown decapitating Medusa, while after that, and in Roman portrayals, he was shown rescuing Andromeda.[18]

Perseus defends Andromeda from the monster Cetus by pelting it with stones. Corinthian amphora, 575–550 BC

Perseus defends Andromeda from the monster Cetus by pelting it with stones. Corinthian amphora, 575–550 BC.jpg.webp)

Roman wall painting of Perseus and Andromeda from Boscotrecase, late 1st century BC

Roman wall painting of Perseus and Andromeda from Boscotrecase, late 1st century BC Detail of Andromeda mosaic from 'House of Poseidon' in Zeugma, Turkey, 2nd–3rd century AD

Detail of Andromeda mosaic from 'House of Poseidon' in Zeugma, Turkey, 2nd–3rd century AD

Variants

There are several variants of the legend. In Hyginus's account, Perseus does not ask for Andromeda's hand in marriage before saving her, and when he afterwards intends to keep her for his wife, both her father Cepheus and her uncle Phineas plot against him, and Perseus resorts to using Medusa's head to turn them to stone.[19] In contrast, Ovid states that Perseus kills Cetus with his magical sword, even though he also carries Medusa's head, which could easily turn the monster to stone (and Perseus does use Medusa's head for this purpose in other situations). The earliest straightforward account of Perseus using Medusa's head against Cetus, however, is from the later 2nd-century AD satirist Lucian.[20]

The 12th-century Byzantine writer John Tzetzes says that Cetus swallows Perseus, who kills the monster by hacking his way out with his sword.[21] Conon places the story in Joppa (Iope or Jaffa, on the coast of modern Israel), and makes Andromeda's uncles Phineus and Phoinix rivals for her hand in marriage; her father Cepheus contrives to have Phoinix abduct her in a ship named Cetos from a small island she visits to make sacrifices to Aphrodite, and Perseus, sailing nearby, intercepts and destroys Cetos and its crew, who are "petrified by shock" at his bravery.[22]

Constellations

Andromeda is represented in the Northern sky by the constellation Andromeda, mentioned by the astronomer Ptolemy in the 2nd century, which contains the Andromeda Galaxy. Several constellations are associated with the myth. Viewing the fainter stars visible to the naked eye, the constellations are rendered as a maiden (Andromeda) chained up, facing or turning away from the ecliptic; a warrior (Perseus), often depicted holding the head of Medusa, next to Andromeda; a huge man (Cepheus) wearing a crown, upside down with respect to the ecliptic; a smaller figure (Cassiopeia) next to the man, sitting on a chair; a whale or sea monster (Cetus) just beyond Pisces, to the south-east; the flying horse Pegasus, who was born from the stump of Medusa's neck after Perseus had decapitated her; the paired fish of the constellation Pisces, that in myth were caught by Dictys the fisherman who was brother of Polydectes, king of Seriphos, the place where Perseus and his mother Danaë were stranded.[23]

In literature

In poetry

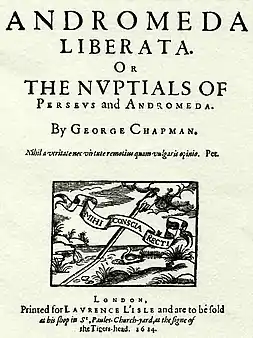

George Chapman's poem in heroic couplets Andromeda liberata, Or the nuptials of Perseus and Andromeda,[24] was written for the 1614 wedding of Robert Carr, 1st Earl of Somerset and Frances Howard. The wedding, which led to a "train of intrigue and murder and executions, was the scandal of the age."[25] Scholars have been surprised that Chapman should have celebrated such a marriage, and his choice of an allegory of the Perseus-Andromeda myth for the purpose. The poem infuriated both Carr and the Earl of Essex, causing Chapman to publish a "justification" of his approach. Chapman's poem sees human nature as chaotic and disorderly, like the sea monster, opposed by Andromeda's beauty and Perseus's balanced nature; their union brings about an astrological harmony of Venus and Mars which perfects the character of Perseus, since Venus was thought always to dominate Mars. Unfortunately for Chapman, Essex supposed that he was represented by the "barraine rocke" that Andromeda was chained up to: Howard had divorced Essex on the grounds that he could not consummate their marriage, and she had married Carr with her hair untied, indicating that she was a virgin. Further, the poem could be read as having dangerous political implications, involving King James.[25]

Ludovico Ariosto's influential epic poem Orlando Furioso (1516–1532) features a pagan princess named Angelica who at one point is in exactly the same situation as Andromeda, chained naked to a rock on the sea as a sacrifice to a sea monster, and is saved at the last minute by the Saracen knight Ruggiero. Images of Angelica and Ruggiero are often hard to distinguish from those of Andromeda and Perseus.[2]

John Keats's 1819 sonnet On the Sonnet compares the restricted sonnet form to the bound Andromeda as being "Fetter'd, in spite of pained loveliness".[26] William Morris retells the story of Perseus and Andromeda in his epic 1868 poem The Earthly Paradise, in the section April: The Doom of King Acrisius.[27] Gerard Manley Hopkins's sonnet Andromeda[28] (1879) has invited many interpretations.[29][30] Charles Kingsley's hexameter poem retelling the myth, Andromeda (1858), was set to music by Cyril Rootham in his Andromeda (1905).[31]

Title page of George Chapman's Andromeda Liberata, 1614, allegorically celebrating the tumultuous marriage of Robert Carr, 1st Earl of Somerset and Frances Howard[25]

Title page of George Chapman's Andromeda Liberata, 1614, allegorically celebrating the tumultuous marriage of Robert Carr, 1st Earl of Somerset and Frances Howard[25] Ruggiero Rescuing Angelica by Gustave Doré illustrates Ludovico Ariosto's epic poem Orlando Furioso, in a scene often confused with the myth of Andromeda.[2]

Ruggiero Rescuing Angelica by Gustave Doré illustrates Ludovico Ariosto's epic poem Orlando Furioso, in a scene often confused with the myth of Andromeda.[2] Doré's 1869 painting of Andromeda

Doré's 1869 painting of Andromeda

In novels

In the 1851 novel Moby-Dick, Herman Melville's narrator Ishmael discusses the Perseus and Andromeda myth in two chapters. Chapter 55, "Of the Monstrous Pictures of Whales," mentions depictions of Perseus rescuing Andromeda from Cetus in artwork by Guido Reni and William Hogarth. In Chapter 82, "The Honor and Glory of Whaling," Ishmael recounts the myth and says that the Romans found a giant whale skeleton in Joppa that they believed to be the skeleton of Cetus.[32][33] Jules Laforgue included what Knutson calls "a remarkable satirical adaptation",[5] "Andromède et Persée", in his 1887 Moralités Légendaires. All the traditional elements are present, along with elements of fantasy and lyricism, but only to allow Laforgue to parody them.[5] The romance, crime, and thriller writer Carlton Dawe's 1909 novel The New Andromeda (published in America as The Woman, the Man, and the Monster) offers what was called at the time a "wholly unconventional"[34] retelling of the Andromeda story in a modern setting.[34][35] Robert Nichols's 1923 short story Perseus and Andromeda satirically retells the story in contrasting styles.[36] In her 1978 novel The Sea, the Sea, Iris Murdoch uses the Andromeda myth, as presented in a reproduction of Titian's painting Perseus and Andromeda in the Wallace Collection in London, to reflect the character and motives of her characters. Charles has an LSD-fuelled vision of a serpent; when he returns to London, he becomes ill on seeing Titian's painting, whereupon his cousin James comes to his rescue.[37]

Herman Melville's 1851 novel Moby-Dick mentions Guido Reni's 17th century painting of Andromeda.[33]

Herman Melville's 1851 novel Moby-Dick mentions Guido Reni's 17th century painting of Andromeda.[33] Titian's Perseus and Andromeda, 1554–1556, features in Iris Murdoch's 1978 novel The Sea, The Sea.[37]

Titian's Perseus and Andromeda, 1554–1556, features in Iris Murdoch's 1978 novel The Sea, The Sea.[37]

In the performing arts

In theatre

The theme, well suited to the stage,[5] was introduced to theatre by Sophocles in his lost tragedy Andromeda (5th century BC), which survives only in fragments. Euripides took up the theme in his play of the same name (412 BC), also now lost, but parodied by Aristophanes in his comedy Thesmophoriazusae (411 BC) and influential in the ancient world. In the parody, Mnesilochus is shaved and dressed as a woman to gain entrance to the women's secret rites, held in honour of the fertility goddess Demeter. Euripides swoops mock-heroically across the stage as Perseus on a theatrical crane, trying and failing to rescue Mnesilochus, who responds by acting out the role of Andromeda.[38]

The legend of Perseus and Andromeda became popular among playwrights in the 17th century, including Lope de Vega's 1621 El Perseo,[39] and Pierre Corneille's famous[5] 1650 verse play Andromède, with dramatic stage machinery effects, including Perseus astride Pegasus as he battles the sea monster. The play, a pièce à machines, presented to King Louis XIV of France and performed by the Comédiens du Roi, the royal troupe, had enormous and lasting success, continuing in production until 1660, to Corneille's surprise.[5][40] The production was a radical departure from the tradition of French theatre, based in part on the Italian tradition of operas about Andromeda; it was semi-operatic, with many songs, set to music by D'Assouci, alongside the stage scenery by the Italian painter Giacomo Torelli. Corneille chose to present Andromeda fully-clothed, supposing that her nakedness had been merely a painterly tradition; Knutson comments that in so doing, "he unintentionally broke the last link with the early erotic myth."[5]

Pedro Calderón de la Barca's 1653 Las Fortunas de Perseo y Andrómeda was also inspired by Corneille,[5] and like El Perseo was heavily embellished with the playwrights' inventions and traditional additions.[39]

Set design for Pierre Corneille's 1650 Andromède, noted for its stage effects: Act 2, where Aeolus and eight winds lift Andromeda into the clouds, with thunder and lightning[40]

Set design for Pierre Corneille's 1650 Andromède, noted for its stage effects: Act 2, where Aeolus and eight winds lift Andromeda into the clouds, with thunder and lightning[40] Andromède, Act 3, where Perseus, riding Pegasus, rescues a fully-clothed Andromeda from the sea monster[40]

Andromède, Act 3, where Perseus, riding Pegasus, rescues a fully-clothed Andromeda from the sea monster[40]

The Andromeda theme was explored later in works such as Muriel Stuart's closet drama Andromeda Unfettered (1922), featuring: Andromeda, "the spirit of woman"; Perseus, "the new spirit of man"; a chorus of "women who desire the old thrall"; and a chorus of "women who crave the new freedom".[41]

In music and opera

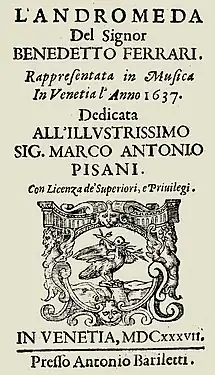

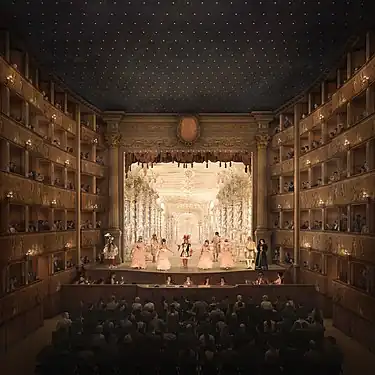

The Andromeda theme has been popular in classical music since the 17th century. It became a theme for opera from the 16th century, with an Andromeda in Italy in 1587.[5] This was followed by Claudio Monteverdi's Andromeda (1618-1620).[42] Benedetto Ferrari's Andromeda, with music by Francesco Manelli, was the first opera performed in a public theatre, Venice's Teatro San Cassiano, in 1637.[43] This set the pattern for Italian opera for several centuries.[44][45]

Jean-Baptiste Lully's Persée (1682), a tragédie lyrique in 5 acts, was inspired by the popularity of Corneille's play.[40] The libretto was by Philippe Quinault, and a real horse appeared on stage as Pegasus.[5] Persée saw an initial run of 33 consecutive performances, 45 in total, exceptional at that time.[5] Written for King Louis XIV, it has been described as Lully's "greatest creation [...] considered the crowning achievement of 17th century French music theatre. Filled with dancing, fight scenes, monsters and special effects [...] [a] truly spectacular opera".[46] Michael Haydn wrote the music for another in 1797.[5] A total of seventeen Andromeda operas were created in Italy in the 18th century.[5]

Other classical works have taken a variety of forms including Andromeda Liberata (1726), a pasticcio-serenata on the subject of Perseus freeing Andromeda, by a team of composers including Vivaldi,[47] and Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf's Symphony in F (Perseus' Rescue of Andromeda) and Symphony in D (The Petrification of Phineus and his Friends), Nos. 4 and 5 of his Symphonies after Ovid's Metamorphoses (c. 1781).

The world's first publicly-performed opera, Benedetto Ferrari's Andromeda, 1637

The world's first publicly-performed opera, Benedetto Ferrari's Andromeda, 1637 Reconstruction of the inauguration of Venice's Teatro San Cassiano in 1637 with Andromeda

Reconstruction of the inauguration of Venice's Teatro San Cassiano in 1637 with Andromeda Title page of Jean-Baptiste Lully's 1682 Persée in 5 acts

Title page of Jean-Baptiste Lully's 1682 Persée in 5 acts

In the 19th century, Augusta Holmès composed the symphonic poem Andromède (1883). In 2019, Caroline Mallonée wrote her Portraits of Andromeda for cello and string orchestra.[48]

In popular music, the theme is employed in tracks on Weyes Blood's 2019 album Titanic Rising and on Ensiferum's 2020 album Thalassic.[49]

In film

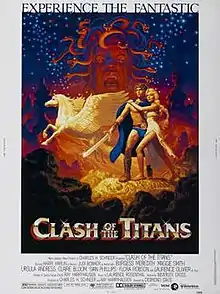

The 1981 film Clash of the Titans is loosely based on the story of Perseus, Andromeda, and Cassiopeia. In the film the monster is a kraken, a giant squid-like sea monster in Norse mythology, rather than the whale-like Cetos of Greek mythology. Perseus defeats the sea monster by showing it Medusa's face to turn it into stone, rather than by using his magical sword, and rides Pegasus.[50]

The 2010 remake with the same title, adapts the original story. Andromeda is set to be sacrificed to the kraken but is saved by Perseus. The historian and filmmaker Henry Louis Gates Jr. criticizes both the original film and its remake for using white actresses to portray the Ethiopian princess Andromeda.[51]

In art

Merged traditions

The legend of Saint George and the Dragon, in which a courageous knight rescues a princess from a monster (with clear parallels to the Andromeda myth), became a popular subject for art in the Late Middle Ages, and artists drew from both traditions. One result is that Perseus is often shown with the flying horse Pegasus when fighting the sea monster, even though classical sources consistently state that he flew using winged sandals.[1]

Classical Roman fresco from Pompeii (before 79 AD) of Perseus, wearing winged sandals, flying in to free Andromeda[1]

Classical Roman fresco from Pompeii (before 79 AD) of Perseus, wearing winged sandals, flying in to free Andromeda[1] Paolo Uccello's 1470 Saint George and the Dragon, illustrating a separate legend that became confused with the story of Perseus and Andromeda, introducing a horse for the hero[1]

Paolo Uccello's 1470 Saint George and the Dragon, illustrating a separate legend that became confused with the story of Perseus and Andromeda, introducing a horse for the hero[1] Piero di Cosimo, Perseus Freeing Andromeda, c. 1510. The hero is depicted with winged sandals, while Andromeda is clothed, unlike in many later paintings.

Piero di Cosimo, Perseus Freeing Andromeda, c. 1510. The hero is depicted with winged sandals, while Andromeda is clothed, unlike in many later paintings. Giuseppe Cesari, Perseus and Andromeda, 1602. The hero is shown riding Pegasus, the flying horse, in a departure from classical myth.[1]

Giuseppe Cesari, Perseus and Andromeda, 1602. The hero is shown riding Pegasus, the flying horse, in a departure from classical myth.[1]

Idealized beauty to realism

Andromeda, and her role in the popular myth of Perseus, has been the subject of numerous ancient and modern works of art, where she is represented as a bound and helpless, typically beautiful, young woman placed in terrible danger, who must be saved through the unswerving courage of a hero who loves her. She is often shown, as by Rubens, with Perseus and the flying horse Pegasus at the moment she is freed.[52] Rembrandt, in contrast, shows a suffering Andromeda, frightened and alone. She is depicted naturalistically, exemplifying the painter's rejection of idealized beauty.[53] Frederic, Lord Leighton's Gothic style 1891 Perseus and Andromeda painting presents the white body of Andromeda in pure and untouched innocence, indicating an unfair sacrifice for a divine punishment that was not directed towards her, but to her mother. Pegasus and Perseus are surrounded by a halo of light that connects them visually to the white body of the princess.[54]

.jpg.webp) Peter Paul Rubens, Perseus and Andromeda, c. 1622, showing the moment that Perseus and Pegasus free Andromeda[52]

Peter Paul Rubens, Perseus and Andromeda, c. 1622, showing the moment that Perseus and Pegasus free Andromeda[52]

Edward Poynter, Andromeda, 1869, depicted as an idealized beauty

Edward Poynter, Andromeda, 1869, depicted as an idealized beauty

Varied materials and approaches

Apart from oil on canvas, artists have used a variety of materials to depict the myth of Andromeda, including the sculptor Domenico Guidi's marble, and François Boucher's etching. In modern art of the 20th century, artists moved to depict the myth in new ways. Félix Vallotton's 1910 Perseus Killing the Dragon is one of several paintings, such as his 1908 The Rape of Europa, in which the artist depicts human bodies using a harsh light which makes them appear brutal.[55] Alexander Liberman's 1962 Andromeda is a black circle on a white field, transected by purple and dark green crescent arcs.[56]

Domenico Guidi, marble statue Andromeda and the Sea Monster, 1694

Domenico Guidi, marble statue Andromeda and the Sea Monster, 1694_-_2016.7_-_Cleveland_Museum_of_Art.tif.jpg.webp) François Boucher, etching print Andromeda, 1732

François Boucher, etching print Andromeda, 1732 Félix Vallotton, Perseus Killing the Dragon, 1910, in a deliberately harsh light. Oil on canvas[55]

Félix Vallotton, Perseus Killing the Dragon, 1910, in a deliberately harsh light. Oil on canvas[55]

Analysis

Ethnicity

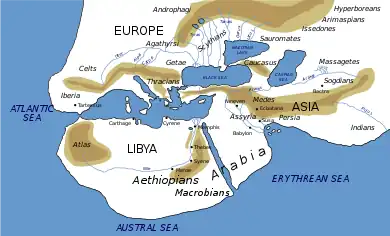

Andromeda was the daughter of the king and queen of Aethiopia, which ancient Greeks located at the edge of the world in Nubia, the lands south of Egypt. The term Aithiops was applied to peoples who dwelt above the equator, between the Atlantic and Indian Oceans.[58] Homer says the Ethiopians live "at the world's end, and lie in two halves, the one looking West and the other East".[59] The 5th-century BC historian Herodotus writes that "Where south inclines westwards, the part of the world stretching farthest towards the sunset is Ethiopia", and also included a plan by Cambyses II of Persia to invade Ethiopia (Kush).[60]

By the 1st century BC a rival location for Andromeda's story had become established: an outcrop of rocks near the ancient port city of Joppa, as reported by Pomponius Mela,[61] the traveller Pausanias,[62] the geographer Strabo,[63] and the historian Josephus.[64] A case has been made that this new version of the myth was exploited to enhance the fame and serve the local tourist trade of Joppa, which also became connected with the biblical story of Jonah and yet another huge sea creature.[65][66] This was at odds with Andromeda's African origins, adding to the confusion already surrounding her ethnicity, as reflected in 5th-century BC Greek vase images showing Andromeda attended by dark-skinned African servants and wearing clothing that would have looked foreign to Greeks, yet with light skin.[67] In the Greek Anthology, Philodemus (1st century BC) wrote about the "Indian Andromeda".[68]

The art historian Elizabeth McGrath discusses the tradition, as promoted by the influential Roman poet Ovid, that Andromeda was a dark-skinned woman of either Ethiopian or Indian origin.[69] In his Heroides, Ovid has Sappho explain to Phaon: "If I'm not pale, Andromeda pleased Perseus, dark with the colour of her father Cepheus's land. And often white pigeons mate with other hues, and the dark turtledove's loved by emerald birds";[70] the Latin word fuscae Ovid uses here for 'dark Andromeda' refers to the colour black or brown. Elsewhere he says that Perseus brought Andromeda from "darkest" India[71] and declares "Nor was Andromeda's colour any problem to her wing-footed aerial lover"[72] adding that "White suits dark girls; you looked so attractive in white, Andromeda".[73] Ovid's account of Andromeda's story[74] follows Euripides' play Andromeda in having Perseus initially mistake the chained Andromeda for a statue of marble, which has been taken to mean she was light-skinned; but since statues in Ovid's time were commonly painted to look like living people, her skin could have been of any colour.[75] The ambiguity is reflected in a description by the 2nd-century AD sophist Philostratus of a painting depicting Perseus and Andromeda. He emphasizes the painting's Ethiopian setting, and notes that Andromeda "is charming in that she is fair of skin though in Ethiopia," in clear contrast to the other "charming Ethiopians with their strange coloring and their grim smiles" who have assembled to cheer Perseus in this picture.[76] Heliodorus of Emesa follows Philostratus in describing Andromeda as light-skinned in contrast to the clearly dark-skinned Aethiopians; in his Aethiopica, Queen Persinna of Aethiopia gives birth to an inexplicably white girl, Chariclea. Heliodorus states that this happened because the queen had gazed at a picture of Andromeda in the palace. The scholar of literature John Michael Archer calls this an example of "how African space is defined by European reference points".[77]

Artworks in the modern era continue to portray Andromeda as fair-skinned, regardless of her stated origins; only a small minority of artists, such as an engraving after Abraham van Diepenbeeck, have chosen to show her as dark. The journalist Patricia Yaker Ekall comments that even this work depicts Andromeda with "European features". She suggests that the "narrative" of white superiority took precedence, and that "the visual of a white man rescuing a chained up black woman would have been too much of a trigger".[3]

.jpg.webp) Engraving after Abraham van Diepenbeeck, The Rescue of Andromeda (1632–1635), from M. de Marolles, Tableaux du Temple des Muses (Paris, 1655), is unusual in showing Andromeda as dark-skinned.[3]

Engraving after Abraham van Diepenbeeck, The Rescue of Andromeda (1632–1635), from M. de Marolles, Tableaux du Temple des Muses (Paris, 1655), is unusual in showing Andromeda as dark-skinned.[3] Eugène Delacroix, Perseus and Andromeda, c. 1853, follows the mainstream in depicting Andromeda as light-skinned.

Eugène Delacroix, Perseus and Andromeda, c. 1853, follows the mainstream in depicting Andromeda as light-skinned.

Bondage and rescue

The imagery of Perseus and Andromeda was depicted by many artists of the Victorian era. Adrienne Munich states that most of these choose the moment after the hero Perseus has killed Medusa and is preparing to "slay the dragon and unbind the maiden".[4] In her view, this transitional moment just precedes "the hero's final test of manhood before entering adult sexuality".[4] Andromeda, on the other hand, "has no story, but she has a role and a lineage", being a princess, and having "attributes: chains, nakedness, flowing hair, beauty, virginity. Without a voice in her fate, she neither defies the gods nor chooses her mate."[4] Munich comments that given that most of the artists were men, "it can be thought of as a male myth", providing convenient gender roles. She cites Catherine MacKinnon's description of the gender differences as "the erotization of dominance and submission": the male gets the power and the female is submissive. Further, the rescue myth provides a "veneer of charity" over the themes of aggression and possession.[4]

Munich likens the effect to John Everett Millais's 1870 painting The Knight Errant, where the knight, "errant like Oedipus", finds a man sexually assaulting a bound and naked woman, which she calls a Freudian "primal scene". The knight kills the man and frees the woman. She asks whether Millais's knight is hiding from the woman's body, or demonstrating self-control, or whether he has "killed his own more aggressive self".[4] She states that similar psychological themes are implied by the story of Perseus and Andromeda: Perseus makes Andromeda into a mother, thus Oedipally "conflating the purpose of his quest with the goal of finding a wife."[4]

As for the bondage, Munich notes that the Victorian critic John Ruskin attacked male exploitation of what she calls "suffering nudes as subjects for titillating pictures."[4] "Andromeda" is, she writes, the name of a type of "debased" imagery. She gives as example Gustave Doré's drawing of the voluptuously chained-up Angelica for Orlando Furioso, where "torment combines with an artistic pose, giving a new meaning to the concept of the 'pin-up'."[4] She notes Ruskin's assertion that the image linked nude prostitutes to the naked Christ, both perverting the meaning of Andromeda's suffering and "blasphem[ing] Christ's sacrifice".[4]

Further, Munich writes, Andromeda's name means 'Ruler of Men', hinting at her power; and indeed, she can be seen as "the good sister" of the monstrous female, the Medusa who turns men to stone. In psychological terms, she comments, "by slaying the Medusa and freeing Andromeda, the hero tames the chaotic female, the very sign of nature, simultaneously choosing and constructing the socially defined and acceptable female behavior."[4]

The scholar of literature Harold Knutson describes the story as having a "disturbing sensuality", which together with the evident injustice of Andromeda's "undeserved sacrifice, create a curiously ambiguous effect".[5] He suggests that in the earlier Palestinian version, the woman was the object of desire, Aphrodite/Ishtar/Astarte, and the hero was the sun god Marduk. The monster was woman in evil form, so chaining her human form would keep her from further evil. Knutson comments that the myth illustrates "the ambiguous male view of the eternal female principle."[5]

Knutson writes that a similar pattern is seen in several other myths, including Heracles' rescue of Hesione; Jason's rescue of Medea from the hundred-eyed dragon; Cadmus's rescue of Harmonia from a dragon; and in an early version of another tale, Theseus's rescue of Ariadne from the Minotaur. He comments that all of this points to "the richness of the [story's] archetypal model", citing Hudo Hetzner's analysis of the many stories that involve a hero rescuing a maiden from a monster. The beast may be a sea-monster, or it may be a dragon that lives in a cave and terrifies a whole country, or the monstrous Count Dracula who lives in a castle.[5]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Whatley, E. Gordon; Thompson, Anne B. Thompson; Upchurch, Robert K., eds. (2004). "St. George and the Dragon: Introduction". Saints' Lives in Middle Spanish Collections. Kalamazoo, Michigan: Medieval Institute Publications. ISBN 978-1-5804-4089-9.

- 1 2 3 "Perseus and Andromeda". National Gallery. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- 1 2 3 Ekall, Patricia Yaker (17 August 2021). "Andromeda: forgotten woman of Greek mythology". Art UK. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Munich, Adrienne (1989). "The Poetics of Rescue, The Politics of Bondage". Andromeda's Chains: Gender and Interpretation in Victorian Literature and Art. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 8–37. ISBN 0-231-06872-7. OCLC 18909224.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Knutson, Harold C. (1992). "Andromeda". In Brunel, Pierre (ed.). Companion to Literary Myths, Heroes, and Archetypes. Routledge. pp. 60–69. ISBN 978-0-4150-6460-6.

- ↑ "Andromeda". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ↑ Both Catasterismi 16 (Hard 2015, p. 19) and De Astronomica 2.10 cite Sophocles' lost play Andromeda as their source for this. According to Hyginus, Fabulae 64 Cassiopeia boasts of her daughter Andromeda's beauty rather than of her own.

- ↑ Grant, Michael; Hazel, John (1993) [1973]. Who's Who in Classical Mythology. Oxford University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-19-521030-9.

- ↑ Kerenyi, Carl (1997). The Heroes of the Greeks. Thames & Hudson. pp. 52–53. ISBN 0-500-27049-X.

- ↑ Hard 2004, pp. 240, 242; Apollodorus, Library 2.4.3; Ovid, Metamorphoses 4.663–5.235; Marcus Manilius, Astronomica, 5.538–618 (pp. 344–51).

- ↑ Hard 2004, p. 242; Apollodorus, Library, 2.4.3.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Library, 2.4.4.

- ↑ Hard 2004, p. 243–4; Apollodorus, Library, 2.4.5. The Hesiodic Catalogue of Women (fr. 241 Most, pp. 346–9) likely listed their children as Alcaeus, Sthenelus and Electryon (Hard 2004, p. 634 n. 113 to p. 243), while Herodorus (FGrHist 31 F15) adds Mestor to these three.

- ↑ Smith, s.v. Andromeda; Catasterismi 17 (Hard 2015, p. 18); see also Hyginus, De Astronomica 2.11.1. The Catasterismi cites Euripides' lost play Andromeda as the source of this account.

- ↑ Vermeule, Cornelius (1963). "Department of Classical Art Annual Report for the Year 1963". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. 88: 33–43. JSTOR 43481008.

- 1 2 Small, Jocelyn Penny (December 1999). "Time in Space: Narrative in Classical Art". The Art Bulletin. 81 (4): 562–575. doi:10.2307/3051334. JSTOR 3051334.

- ↑ Beeson, A. J. (1986). "Perseus and Andromeda as lovers. A mosaic panel from Brading and its origins". Mosaic (17): 13–19.

- ↑ Karoglou, Kiki (2018). "Dangerous Beauty: Medusa in Classical Art". Museum of Art Bulletin. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 73 (3): 11. ISBN 978-1-58839-642-6.

- ↑ Hyginus, Fabulae, 64.

- ↑ Lucian, The Hall 22 (pp. 200, 201).

- ↑ Tzetzes on Lycophron, 836 (pp. 820–1).

- ↑ Conon, Narrations, 40 (Trzaskoma, Smith and Brunet, p. 88).

- ↑ Thompson, Robert Bruce; Thompson, Barbara Fritchman (2007). Illustrated Guide to Astronomical Wonders. O'Reilly. pp. 66–73. ISBN 978-0-596-52685-6.

- ↑ Chapman, George. Andromeda liberata. University of Michigan. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- 1 2 3 Waddington, Raymond B. (1966). "Chapman's Andromeda Liberata: Mythology and Meaning". Publications of the Modern Language Association of America. 81 (1): 34–44. doi:10.2307/461306. JSTOR 461306. S2CID 164121070.

- ↑ Brady, Andrea (October 2021). "The Fetters of Verse". Introduction - The Fetters of Verse. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–28. doi:10.1017/9781108990684.001. ISBN 978-1-108-99068-4. S2CID 242479172. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- ↑ Silver, Carole G. (1975). "'The Earthly Paradise': Lost". Victorian Poetry. 13 (3/4): 27–42. JSTOR 40001829.

- ↑ Hopkins, Gerard Manley (1879) Andromeda

- ↑ Mariani, Paul L. "Hopkins' "Andromeda" and the New Aestheticism," Victorian Poetry, Vol. 11, No. 1 (Spring, 1973), pp. 39-54

- ↑ Mariani, Paul L. (1973). "Hopkins' Andromeda and the New Aestheticism". Victorian Poetry. 11 (1): 39–54. JSTOR 40001776.

- ↑ "Andromeda Cartoons by Matt Lawrence". Cantata Dramatica. 2015. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

Some of the cartoons are accompanied by extracts from a recording made in 2019, a full version of which can be heard on the website of Cyril Bradley Rootham.

- ↑ Melville, Herman (1851). Moby-Dick.

- 1 2 Pardes, Ilana (2005). "Remapping Jonah's Voyage: Melville's "Moby-Dick" and Kitto's "Cyclopedia of Biblical Literature"". Comparative Literature. 57 (2): 135–157. doi:10.1215/-57-2-135. JSTOR 4122318.

- 1 2 "[Review] The Woman, The Man and the Monster". Salt Lake Tribune. 20 June 1909.

- ↑ Carter, David; Osborne, Roger (2018). Australian Books and Authors in the American Marketplace 1840s-1940s. Sydney University Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-7433-2579-7.

- ↑ Nichols, Robert. "Perseus and Andromeda", Fantastica: being the smile of the Sphinx and other tales of imagination, Macmillan, 1923. The variant tales are on pages 75ff, 87ff, and 95ff respectively.

- 1 2 Tucker, Lindsey (1986). "Released from Bands: Iris Murdoch's Two Prosperos in "The Sea, The Sea"". Contemporary Literature. 27 (3): 378–395. doi:10.2307/1208351. JSTOR 1208351.

- ↑ Sfyroeras, Pavlos (2008). "Πóθος Εὐριπíδου: Reading "Andromeda" in Aristophanes' "Frogs"". The American Journal of Philology. 129 (3): 299–317. doi:10.1353/ajp.0.0014. JSTOR 27566713. S2CID 161684940.

- 1 2 Martin, Henry M. (1931). "The Perseus Myth in Lope de Vega and Calderon With Some Reference to Their Sources". Publications of the Modern Language Association of America. 46 (2): 450–460. doi:10.2307/458043. ISSN 0030-8129. JSTOR 458043. S2CID 163848591.

- 1 2 3 4 Williams, Wes (January 2007). "'For Your Eyes Only': Corneille's View of Andromeda". Classical Philology. 102 (1): 110–123. doi:10.1086/521136. S2CID 162104879.

- ↑ Stuart, Muriel. "Andromeda Unfettered". Verse Press. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ↑ Rosenthal, Albi (January 1985). "Monteverdi's 'Andromeda': A Lost Libretto Found". Music & Letters. 66 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1093/ml/66.1.1. JSTOR 855431.

- ↑ L'Andromeda, Antonio Bariletti, Venice, 1637, p. 3.

- ↑ Bianconi, Lorenzo (1987). Music in the Seventeenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 183.

the Venetian-type theatre [...] comes to represent something of an economic and architectural prototype for Italy and Europe as a whole. At least architecturally, this prototype still survives essentially unchanged...

- ↑ Rosand, Ellen (1990). "3 Da rappresentare in musica: The Rise of Commercial Opera". Opera in Seventeenth-Century Venice. Berkeley: University of California Press. Archived from the original on 31 December 2022.

- ↑ "Jean-Baptiste Lully: Persée". EuroArts. Prog. No. 5417. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ↑ Cookson, Michael. "[Review] Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) Serenata Veneziana - Andromeda Liberata". Music Web International. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ↑ "A Buffalo composer puts Andromeda—constellation, myth and meteors—to music". 2 May 2019.

- ↑ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Ensiferum - Andromeda (OFFICIAL VIDEO)". YouTube.

- ↑ Gloyn, Liz (2012). "'The Dragon-Green, the Luminous, the Dark, the Serpent-Haunted Sea': Monsters, Landscape and Gender In Clash of the Titans (1981 and 2010)" (PDF). NEW VOICES IN CLASSICAL RECEPTION STUDIES Conference Proceedings. 1: 64–75.

- 1 2 Gates, Henry Louis Jr. (17 Feb 2014). "Was Andromeda Black?". Roots.

- 1 2 Baumbach, Manuel (2010). "Pegasus". In Grafton, Anthony; Most, Glenn W.; Settis, Salvatore (eds.). The Classical Tradition. Harvard University Press. p. 699.

- 1 2 Clark, Kenneth (1966). Rembrandt and the Italian Renaissance. New York University Press. p. 11.

- 1 2 "andromeda". Loggia.com. Archived from the original on 14 April 2015. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- 1 2 "Biography". Félix Vallotton. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ↑ "Alexander Liberman: Andromeda: 1962". Tate Gallery. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ↑ For all references to Aethiopia in Herodotus, see: this list at the Perseus Project.

- ↑ Thompson, Lloyd A. (1989). Romans and blacks. Taylor & Francis. p. 57. ISBN 0-415-03185-0.

- ↑ Homer, Odyssey 1.22–24; Homer established a long-standing literary tradition that Ethiopia was an idyllic land of plenty where the gods attended feasts. MacLachlan, Bonnie (1992). "Feasting with Ethiopians: Life on the Fringe". Quaderni Urbinati di Cultura Classica. 40 (1): 15–33. doi:10.2307/20547123. JSTOR 20547123.

- ↑ Herodotus, Histories 3.114, 3.94, 7.70.

- ↑ Pomponius Mela, 1.64.

- ↑ Pausanias, 4.35.9.

- ↑ Strabo, 1.2.35, 16.2.28.

- ↑ Josephus, Jewish War 3.9.3.

- ↑ Harvey, Paul Jr., "The death of mythology: the case of Joppa", Journal of Early Christian Studies, January 1994, Vol. 2 Issue: Number 1 p. 1-14

- ↑ Kaizer, Ted (2011). "Interpretations of the Myth of Andromeda at Iope" (PDF). Syria. 88 (88): 323–339. doi:10.4000/syria.939. JSTOR 41682313. S2CID 190063227.

- ↑ "Pelike".

- ↑ Greek Anthology, 5.132 (English translation; Greek text).

- ↑ McGrath, Elizabeth (1992). "The Black Andromeda". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 55: 1–18. doi:10.2307/751417. JSTOR 751417. S2CID 195025221.

- ↑ Ovid, Heroides, 15.35–38.

- ↑ Ovid, Ars Amatoria 1.53.

- ↑ Ovid, Ars Amatoria 2.643–644.

- ↑ Ovid, Ars Amatoria 3.191–192.

- ↑ Ovid, Metamorphoses 4.665 ff.

- ↑ Koch-Brinkmann, Ulrike; Dreyfus, Renée; Brinkmann, Vinzenz (2017). Gods in colour: polychromy in the ancient world. San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Legion of Honor. ISBN 978-3-7913-5707-2. OCLC 982089362.

- ↑ Philostratus, Imagines 1.29.

- ↑ Archer, John Michael (2001). Old Worlds: Egypt, Southwest Asia, India, and Russia in Early Modern English Writing. Stanford University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-8047-4337-2.

Sources

- Apollodorus, Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1921. ISBN 0-674-99135-4. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Hard, Robin (2004), The Routledge Handbook of Greek Mythology: Based on H.J. Rose's "Handbook of Greek Mythology", Psychology Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-415-18636-0. Google Books.

- Hard, Robin (2015), Eratosthenes and Hyginus: Constellation Myths, With Aratus's Phaenomena, Oxford University Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0-19-871698-3. Google Books.

- Herodotus, Histories, translated by A. D. Godley, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 1920. ISBN 0674991338. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Hesiod, Catalogue of Women, in Hesiod: The Shield, Catalogue of Women, Other Fragments, edited and translated by Glenn W. Most, Loeb Classical Library No. 503, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 2007, 2018. ISBN 978-0-674-99721-9. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Hyginus, Gaius Julius, De Astronomica, in The Myths of Hyginus, edited and translated by Mary A. Grant, Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1960. Online version at ToposText.

- Hyginus, Gaius Julius, Fabulae, in The Myths of Hyginus, edited and translated by Mary A. Grant, Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1960. Online version at ToposText.

- Lucian, Phalaris. Hippias or The Bath. Dionysus. Heracles. Amber or The Swans. The Fly. Nigrinus. Demonax. The Hall. My Native Land. Octogenarians. A True Story. Slander. The Consonants at Law. The Carousal (Symposium) or The Lapiths, translated by A. M. Harmon, Loeb Classical Library No. 14, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 1913. ISBN 978-0-674-99015-9. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Manilius, Astronomica, edited and translated by G. P. Goold, Loeb Classical Library No. 469, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 1977. ISBN 978-0-674-99516-1. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses, edited and translated by Brookes More, Boston, Cornhill Publishing Co., 1922. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library. Online version at ToposText.

- Pausanias, Pausanias Description of Greece with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D., and H.A. Ormerod, M.A., in 4 Volumes, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Smith, William, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, London (1873). Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Strabo, Geography, edited and translated by H.C. Hamilton, Esq., W. Falconer, M.A., London, George Bell & Sons, 1903. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Trzaskoma, Stephen M., R. Scott Smith, and Stephen Brunet, Anthology of Classical Myth: Primary Sources in Translation, Hackett Publishing, 2004. ISBN 0-87220-721-8. Google Books.

- Tzetzes, John, Scolia eis Lycophroon, edited by Christian Gottfried Müller, Sumtibus F.C.G. Vogelii, 1811. Internet Archive.

Further reading

- Edwin Hartland, The Legend of Perseus: A Study of Tradition in Story, Custom and Belief, 3 vols. (1894-1896) ISBN 1481035738 (available online at: https://archive.org/details/legendofperseuss01hart/page/n6/mode/2up)

- Daniel Ogden, Perseus (Routledge, 2008) ISBN 0415427258