Beurtvaart was a Dutch line shipping system for (mostly) inland navigation, that existed from the late 15th century. It was a form of packet trade and a precursor of public transport. The beurtships transported passengers, livestock and freight along fixed routes at fixed prices. Departures were scheduled, with ships even sailing when not fully laden, and local authorities took legal measures to rule out the competition.

Background

The Netherlands is a country particularly rich in waterways. Next to many natural ones, a fair number of canals have been dug over the centuries. Between 1632 and 1665 alone, in the heyday of the Dutch Golden Age, 658 km of canal was constructed by cities and investors. Also, the Zuiderzee, a large body of water in the middle of the northern part of the country, was a major interchange for shipping. Roads on the other hand, were of poor quality if they existed at all. A road network of some significance wasn't constructed until the early 19th century. Consequently, all cities of any importance were on a waterfront and water transport between them grew with an expanding economy from the late 15th century.

Before the beurtvaart, merchants had to hire an entire ship if they wanted something transported, although middlemen like shipbrokers probably saw to some break bulk cargo as well. From the end of the 15th century wealth and trade were growing in the Netherlands, pushing the demand for transportation. Meanwhile, the cities increasingly involved themselves in regulating the transport business, primarily to advance their own skippers at the expense of those from other places. For instance, the right of lastbreken meant that a shipment of goods had to be unloaded upon arrival, involving fees for porters, warehouses and such. The medieval staple right is another example. As competing skippers would regularly get involved in fistfights over rights, shipments and times to load and sail, the cities made more and more rules and regulations.

The system

Beurtvaart was set up as a contract between two cities or a city and a lord. The two would enter negotiations to establish the demand for transport, fix prices and schedules, and make a list of requirements for the ships and the skippers. Then ship owners were bound to the system by licenses and competition was made impossible. For instance, merchants shipping goods to another city were obliged to make use of the beurtvaart. On the other hand, ships had to sail at scheduled times, fully laden or not. The system guaranteed travellers and merchants reliable shipping at fixed prices and it provided the skippers with a reasonable income, even in bad times.

The skippers were organised in guilds, that further regulated the system and saw to day-to-day operations. Sometimes a guild would own the ships collectively, but in most of the cases the skipper owned the ship he sailed. The cities had the ships inspected yearly and made increasingly long lists of requirements for ship and skipper, with fines for all kinds of reasons.

The freight carried was usually break bulk cargo, while bulk was left to an early form of tramp trade. The passenger service of the trekschuit was related to the beurtvaart, but not the same thing.

The system evolved in the course of more than a century, with the beurtvaart coming of age around 1600.

Open sea, international

While most ships sailed inland, the beurtships also travelled the open sea, like the Zuiderzee and the Wadden Sea. Amsterdam had beurtvaart contacts with London and Rouen from 1611, Hamburg in 1613 and Dunkirk in 1699. In the Southern Netherlands the system flourished as well, but only in the western parts. Some German cities had beurtvaart connections with Dutch ones, and after that between them as well.

History

Some form of scheduled transportation probably originated in the 15th century, with marktveren (market ferries) providing reliable transport of goods into the cities on market days. Most of these connections were maintained by the skippers or their guilds. In 1488 a veer was organised between the towns of Antwerp and Veere, with a certain amount of regulation. In 1510 a veer was arranged by skippers between Amsterdam and Spaarndam and ten years later one between Haarlem and Amsterdam, regulated unilaterally by the latter. The fee for one traveller was set at five stuivers, double that in the case of bad weather.

In 1529 a bilaterally organised beurtveer was arranged between Hoorn and Amsterdam. Especially in the second half of the 16th century connections were established between most of the major cities and some of the minor ones as well. In 1594 The Hague regulated a line to Amsterdam unilaterally. It was the first time a legal monopoly for local skippers went hand in hand with the obligation to sail at scheduled times, which became the habit of the system.

After this, the beurtvaart grew to an extensive network spanning the coastal provinces of the Netherlands, most prominently Holland. An observer in Amsterdam in 1765 estimated some 800 departures to 180 destinations weekly. One source states that the beurtvaart system is in part responsible for the fact that in the Netherlands not one port was growing to dominate the sea trade, as was the case in surrounding countries.[1]

When early 19th century the guilds were legally abolished, the beurtvaart system was continued by royal decree. Later that century however, when the age of liberalism came to the Netherlands, pressure was on to end the system. In 1841 in the legal protection of the beurtvaart national government made an exception for steamship companies. Between 1859 and 1880 local and national authorities withdrew legal intervention, ending the beurtvaart in a stricter sense.

Shipping companies

With legal protection withdrawn, and under competition from the railways, inland line shipping did not wither: it flourished instead. Main reasons for this are the industrialisation in the Netherlands and Germany, greatly pushing the demand for transportation, and the fact that the Dutch network of waterways is far more intricate than the railways would ever be.

In the innovative time of iron built steam ships, a great number of small shipping companies sprang up. They were known as beurtvaartrederijen (beurtvaart shipping companies) and they continued to provide scheduled services between local ports. At first, all of them carried passengers, livestock and freight, but some withdrew to passenger service only, becoming more like public transport companies.

Some companies grew, others merged and a few went bankrupt, but overall they were quite successful. In 1872 164 steamships were in service, owned by 110 entrepreneurs, most of them on one route. By 1890 the number had grown to 201. Company revenue was good in this period, with a per annum dividend of 8-10% for most of them, and more for some.

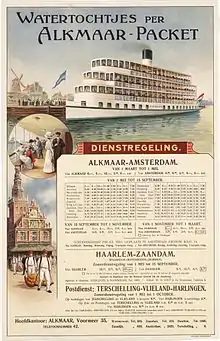

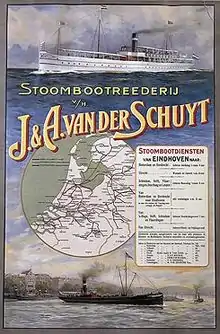

Companies like Alkmaar Packet and Verschure & Co. at some point each owned in excess of 20 ships. The largest was J. & A. van der Schuyt, which operated 78 steam vessels in 1917.

Belgium

The young country of Belgium had chosen to rapidly build an intricate railway network, which would carry freight to a greater extent than the Dutch one. For these reasons in Belgium beurtvaart companies were not of the importance they had in the northern Netherlands.

Shipping company posters

Haven-Stoombootdienst, around 1890

Haven-Stoombootdienst, around 1890 Deventer-Amsterdammer Stoomboot Reederij, 1900

Deventer-Amsterdammer Stoomboot Reederij, 1900 Fop Smit, 1905

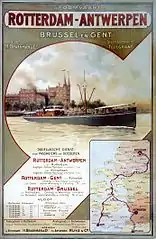

Fop Smit, 1905 H. Braakman & Co, 1907

H. Braakman & Co, 1907 Alkmaar Packet, 1913

Alkmaar Packet, 1913 Holland-Friesland, 1915

Holland-Friesland, 1915 J. & A. van der Schuyt, before 1923

J. & A. van der Schuyt, before 1923

Other beurtvaart

Without the legal protection, individual ship owners mostly just continued their businesses, although some of them withdrew from passenger service. From the 1920s onward, they could maintain a business by switching to the internal combustion engine, for which investment and operating cost were not as high as for steam engines. Two sources estimate the number of inland ships in service of the beurtvaart around 1890 to be a 1000. A government agency counted 1804 of them in 1910.

Competition, war

Between the 1910s and the late 1930s Dutch inland navigation faced growing competition from the railways, but especially from the truck, as both trucks and roads were getting better. Truck transport is profitable at a much lower rate of loading than a steam ship. During the time of the Great Depression this competing edge became painfully clear, with numbers of ships and shipping lines declining fast after 1934. Some companies started to operate truck lines of their own, at first to service their ships and later competing with them.

WWII and after

World War II was an outright disaster for the industry, as ships were lost to acts of war or were claimed. Companies like Van der Schuyt lost ships, the yard and offices in the Rotterdam Blitz. Large exclusion zones imposed by German forces meant a lot less demand for transportation. Getting back in business after the war proved difficult for all inland shipping companies, impossible for some. Especially the years 1947 and 1948 saw many liquidations, mergers and some shipping lines becoming trucking companies. A few inland lines kept operating into the 1960s, but by 1970 beurtvaart had ended.

See also

Sources

- Brouwer, P. and G. van Kesteren, with A. Wiersma (2008); Berigt aan de heeren reizigers. 400 jaar openbaar vervoer in Nederland; Sdu uitgevers, Den Haag. ISBN 9789012114806.

- Filarski, R. (2014); Tegen de stroom in. Binnenvaart en vaarwegen vanaf 1800, Utrecht. ISBN 9789053454770

- Sepp, J. (2011); De Beurtvaart, on the website of the Dutch Association for the Preservation of Historical Business Vessels.

- ↑ Ormrod, D. (2003); The Rise of Commercial Empires. England and the Netherlands in the Age of Mercantilism, 1650–1770, Cambridge, p. 13. Online here, retrieved 4 April 2015.