The Bethe formula or Bethe–Bloch formula describes the mean energy loss per distance travelled of swift charged particles (protons, alpha particles, atomic ions) traversing matter (or alternatively the stopping power of the material).[1] For electrons the energy loss is slightly different due to their small mass (requiring relativistic corrections) and their indistinguishability, and since they suffer much larger losses by Bremsstrahlung, terms must be added to account for this. Fast charged particles moving through matter interact with the electrons of atoms in the material. The interaction excites or ionizes the atoms, leading to an energy loss of the traveling particle.

The non-relativistic version was found by Hans Bethe in 1930; the relativistic version (shown below) was found by him in 1932.[2] The most probable energy loss differs from the mean energy loss and is described by the Landau-Vavilov distribution.[3]

The formula

For a particle with speed v, charge z (in multiples of the electron charge), and energy E, traveling a distance x into a target of electron number density n and mean excitation energy I (see below), the relativistic version of the formula reads, in SI units:[2]

-

(1)

where c is the speed of light and ε0 the vacuum permittivity, , e and me the electron charge and rest mass respectively.

Here, the electron density of the material can be calculated by

where ρ is the density of the material, Z its atomic number, A its relative atomic mass, NA the Avogadro number and Mu the Molar mass constant.

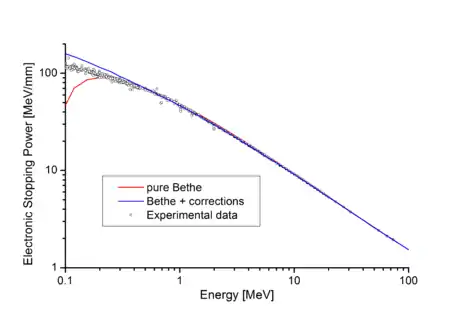

In the figure to the right, the small circles are experimental results obtained from measurements of various authors, while the red curve is Bethe's formula.[4] Evidently, Bethe's theory agrees very well with experiment at high energy. The agreement is even better when corrections are applied (see below).

For low energies, i.e., for small velocities of the particle β << 1, the Bethe formula reduces to

-

(2)

This can be seen by first replacing βc by v in eq. (1) and then neglecting β2 because of its small size.

At low energy, the energy loss according to the Bethe formula therefore decreases approximately as v−2 with increasing energy. It reaches a minimum for approximately E = 3Mc2, where M is the mass of the particle (for protons, this would be about at 3000 MeV). For highly relativistic cases β ≈ 1, the energy loss increases again, logarithmically due to the transversal component of the electric field.

The mean excitation energy

In the Bethe theory, the material is completely described by a single number, the mean excitation energy I. In 1933 Felix Bloch showed that the mean excitation energy of atoms is approximately given by

-

(3)

where Z is the atomic number of the atoms of the material. If this approximation is introduced into formula (1) above, one obtains an expression which is often called Bethe-Bloch formula. But since we have now accurate tables of I as a function of Z (see below), the use of such a table will yield better results than the use of formula (3).

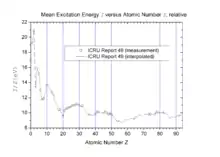

The figure shows normalized values of I, taken from a table.[5] The peaks and valleys in this figure lead to corresponding valleys and peaks in the stopping power. These are called "Z2-oscillations" or "Z2-structure" (where Z2 = Z means the atomic number of the target).

Corrections to the Bethe formula

The Bethe formula is only valid for energies high enough so that the charged atomic particle (the ion) does not carry any atomic electrons with it. At smaller energies, when the ion carries electrons, this reduces its charge effectively, and the stopping power is thus reduced. But even if the atom is fully ionized, corrections are necessary.

Bethe found his formula using quantum mechanical perturbation theory. Hence, his result is proportional to the square of the charge z of the particle. The description can be improved by considering corrections which correspond to higher powers of z. These are: the Barkas-Andersen-effect (proportional to z3, after Walter H. Barkas and Hans Henrik Andersen), and the Felix Bloch-correction (proportional to z4). In addition, one has to take into account that the atomic electrons of the material traversed are not stationary ("shell correction").

The corrections mentioned have been built into the programs PSTAR and ASTAR, for example, by which one can calculate the stopping power for protons and alpha particles.[6] The corrections are large at low energy and become smaller and smaller as energy is increased.

At very high energies, Fermi's density correction[5] has to be added.

See also

References

- ↑ Bethe, H.; Ashkin, J. (1953). Segré, E. (ed.). Experimental Nuclear Physics. New York: J. Wiley. p. 253.

- 1 2 Sigmund, Peter Particle Penetration and Radiation Effects. Springer Series in Solid State Sciences, 151. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-31713-9 (2006)

- ↑ Bichsel, Hans (1988-07-01). "Straggling in thin silicon detectors". Reviews of Modern Physics. American Physical Society (APS). 60 (3): 663–699. doi:10.1103/revmodphys.60.663. ISSN 0034-6861.

- ↑ "Stopping Power for Light and Heavier Ions". 2015-04-15. Retrieved 2015-11-01.

- 1 2 Report 49 of the International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements, "Stopping Powers and Ranges for Protons and Alpha Particles", Bethesda, MD, USA (1993)

- ↑ NISTIR 4999, Stopping Power and Range Tables

External links

- The Straggling function. Energy Loss Distribution of charged particles

- Original Publication: Zur Theorie des Durchgangs schneller Korpuskularstrahlen durch Materie in "Annalen der Physik", Vol. 397 (1930) 325 -400

- Passage of charged particles through matter, with a graph

- Stopping power for protons and alpha particles

- Stopping Power graphs and data

- Recent numerical solutions