The first day of the Battle of Gettysburg during the American Civil War took place on July 1, 1863, and began as an engagement between isolated units of the Army of Northern Virginia under Confederate General Robert E. Lee and the Army of the Potomac under Union Maj. Gen. George G. Meade. It soon escalated into a major battle which culminated in the outnumbered and defeated Union forces retreating to the high ground south of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

The first-day battle proceeded in three phases as combatants continued to arrive at the battlefield. In the morning, two brigades of Confederate Maj. Gen. Henry Heth's division (of Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill's Third Corps) were delayed by dismounted Union cavalrymen under Brig. Gen. John Buford. As infantry reinforcements arrived under Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds of the Union I Corps, the Confederate assaults down the Chambersburg Pike were repulsed, although Gen. Reynolds was killed.

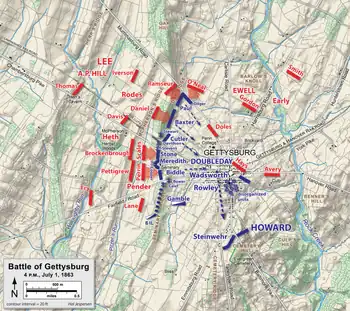

By early afternoon, the Union XI Corps, commanded by Major General Oliver Otis Howard, had arrived, and the Union position was in a semicircle from west to north of the town. The Confederate Second Corps under Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell began a massive assault from the north, with Maj. Gen. Robert E. Rodes's division attacking from Oak Hill and Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early's division attacking across the open fields north of town. The Union lines generally held under extremely heavy pressure, although the salient at Barlow's Knoll was overrun.

The third phase of the battle came as Rodes renewed his assault from the north and Heth returned with his entire division from the west, accompanied by the division of Maj. Gen. W. Dorsey Pender. Heavy fighting in Herbst's Woods (near the Lutheran Theological Seminary) and on Oak Ridge finally caused the Union line to collapse. Some of the Federals conducted a fighting withdrawal through the town, suffering heavy casualties and losing many prisoners; others simply retreated. They took up good defensive positions on Cemetery Hill and waited for additional attacks. Despite discretionary orders from Robert E. Lee to take the heights "if practicable," Richard Ewell chose not to attack. Historians have debated ever since how the battle might have ended differently if he had found it practicable to do so.

Background

Military situation

Opposing forces

Union

Confederate

Morning

Defense by Buford's cavalry

On the morning of July 1, Union cavalry in the division of Brigadier General John Buford were awaiting the approach of Confederate infantry forces from the direction of Cashtown, to the northwest. Confederate forces from the brigade of Brig. Gen. J. Johnston Pettigrew had briefly clashed with Union forces the day before but believed they were Pennsylvania militia of little consequence, not the regular army cavalry that was screening the approach of the Army of the Potomac.[1]

General Buford recognized the importance of the high ground directly to the south of Gettysburg. He knew that if the Confederates could gain control of the heights, Meade's army would have a hard time dislodging them.[lower-alpha 1] He decided to utilize three ridges west of Gettysburg: Herr Ridge, McPherson Ridge, and Seminary Ridge (proceeding west to east toward the town). These were appropriate terrain for a delaying action by his small division against superior Confederate infantry forces, meant to buy time awaiting the arrival of Union infantrymen who could occupy the strong defensive positions south of town, Cemetery Hill, Cemetery Ridge, and Culp's Hill.[3] Early that morning, Reynolds, who was commanding the Left Wing of the Army of the Potomac, ordered his corps to march to Buford's location, with the XI Corps (Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard) to follow closely behind.[4]

Confederate Maj. Gen. Henry Heth's division, from Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill's Third Corps, advanced towards Gettysburg. Heth deployed no cavalry and led, unconventionally, with the artillery battalion of Major William J. Pegram.[5] Two infantry brigades followed, commanded by Brig. Gens. James J. Archer and Joseph R. Davis, proceeding easterly in columns along the Chambersburg Pike. Three miles (4.8 km) west of town, about 7:30 a.m., Heth's two brigades met light resistance from cavalry vedettes and deployed into line. Eventually, they reached dismounted troopers from Col. William Gamble's cavalry brigade. The first shot of the battle was claimed to be fired by Lieutenant Marcellus E. Jones of the 8th Illinois Cavalry, fired at an unidentified man on a gray horse over a half-mile away; the act was merely symbolic.[6] Buford's 2,748 troopers would soon be faced with 7,600 Confederate infantrymen, deploying from columns into line of battle.[7]

Gamble's men mounted determined resistance and delaying tactics from behind fence posts with rapid fire, mostly from their breech-loading carbines. While none of the troopers were armed with multi-shot repeating carbines, they were able to fire two or three times faster than a muzzle-loaded carbine or rifle with their breechloading carbines manufactured by Sharps, Burnside, and others.[8] (A small minority of historians have written that some troopers had Spencer repeating carbines or Spencer repeating rifles but most sources disagree.)[9][lower-alpha 2] The breech-loading design of the carbines and rifles meant that Union troops did not have to stand to reload and could do so safely behind cover. This was a great advantage over the Confederates, who still had to stand to reload, thus providing an easier target. But this was so far a relatively bloodless affair. By 10:20 a.m., the Confederates had reached Herr Ridge and had pushed the Federal cavalrymen east to McPherson Ridge, when the vanguard of the I Corps finally arrived, the division of Maj. Gen. James S. Wadsworth. The troops were led personally by Gen. Reynolds, who conferred briefly with Buford and hurried back to bring more men forward.[10]

Davis versus Cutler

The morning infantry fighting occurred on either side of the Chambersburg Pike, mostly on McPherson Ridge. To the north, an unfinished railroad bed opened three shallow cuts in the ridges. To the south, the dominant features were Willoughby Run and Herbst Woods (sometimes called McPherson Woods, but they were the property of John Herbst). Brig. Gen. Lysander Cutler's Union brigade opposed Davis's brigade; three of Cutler's regiments were north of the Pike, two to the south. To the left of Cutler, Brig. Gen. Solomon Meredith's Iron Brigade opposed Archer.[11]

General Reynolds directed both brigades into position and placed guns from the Maine battery of Capt. James A. Hall where Calef's had stood earlier.[12] While the general rode his horse along the east end of Herbst Woods, shouting "Forward men! Forward for God's sake, and drive those fellows out of the woods," he fell from his horse, killed instantly by a bullet striking him behind the ear. (Some historians believe Reynolds was felled by a sharpshooter, but it is more likely that he was killed by random shot in a volley of rifle fire directed at the 2nd Wisconsin.) Maj. Gen. Abner Doubleday assumed command of the I Corps.[13]

On the right of the Union line, three regiments of Cutler's brigade were fired on by Davis's brigade before they could get into position on the ridge. Davis's line overlapped the right of Cutler's, making the Union position untenable, and Wadsworth ordered Cutler's regiments back to Seminary Ridge. The commander of the 147th New York, Lt. Col. Francis C. Miller, was shot before he could inform his troops of the withdrawal, and they remained to fight under heavy pressure until a second order came. In under 30 minutes, 45% of Gen. Cutler's 1,007 men became casualties, with the 147th losing 207 of its 380 officers and men.[14] Some of Davis's victorious men turned toward the Union positions south of the railroad bed while others drove east toward Seminary Ridge. This defocused the Confederate effort north of the pike.[15]

Archer versus Meredith

South of the pike, Archer's men were expecting an easy fight against dismounted cavalrymen and were astonished to recognize the black Hardee hats worn by the men facing them through the woods: the famous Iron Brigade, formed from regiments in the Western states of Indiana, Michigan, and Wisconsin, had a reputation as fierce, tenacious fighters. As the Confederates crossed Willoughby Run and climbed the slope into Herbst Woods, they were enveloped on their right by the longer Union line, the reverse of the situation north of the pike.[16]

Brig. Gen. Archer was captured in the fighting, the first general officer in Robert E. Lee's army to suffer that fate. Archer was most likely positioned around the 14th Tennessee when he was captured by Private Patrick Moloney of Company G., 2nd Wisconsin, "a brave patriotic and fervent young Irishman." Archer resisted capture, but Moloney overpowered him. Moloney was killed later that day, but he received the Medal of Honor for his exploit. When Archer was taken to the rear, he encountered his former Army colleague Gen. Doubleday, who greeted him good-naturedly, "Good morning, Archer! How are you? I am glad to see you!" Archer replied, "Well, I am not glad to see you by a damn sight!"[17]

Railroad cut

At around 11 a.m., Doubleday sent his reserve regiment, the 6th Wisconsin, an Iron Brigade regiment, commanded by Lt. Col. Rufus R. Dawes, north in the direction of Davis's disorganized brigade. The Wisconsin men paused at the fence along the pike and fired, which halted Davis's attack on Cutler's men and caused many of them to seek cover in the unfinished railroad cut. The 6th joined the 95th New York and the 84th New York (also known as the 14th Brooklyn), a "demi-brigade" commanded by Col. E.B. Fowler, along the pike.[14] The three regiments charged to the railroad cut, where Davis's men were seeking cover. The majority of the 600-foot (180 m) cut (shown on the map as the center cut of three) was too deep to be an effective firing position—as deep as 15 feet (4.6 m).[18] Making the situation more difficult was the absence of their overall commander, General Davis, whose location was unknown.[19]

The men of the three regiments nevertheless faced daunting fire as they charged toward the cut. The 6th Wisconsin's American flag went down at least three times during the charge. At one point Dawes took up the fallen flag before it was seized from him by a corporal of the color guard. As the Union line neared the Confederates, its flanks became folded back and it took on the appearance of an inverted V. When the Union men reached the railroad cut, vicious hand-to-hand and bayonet fighting broke out. They were able to pour enfilading fire from both ends of the cut, and many Confederates considered surrender. Colonel Dawes took the initiative by shouting "Where is the colonel of this regiment?" Major John Blair of the 2nd Mississippi stood up and responded, "Who are you?" Dawes replied, "I command this regiment. Surrender or I will fire."[20] Dawes later described what happened next:[21]

The officer replied not a word, but promptly handed me his sword, and his men, who still held them, threw down their muskets. The coolness, self possession, and discipline which held back our men from pouring a general volley saved a hundred lives of the enemy, and as my mind goes back to the fearful excitement of the moment, I marvel at it.

— Col. Rufus R. Dawes, Service with the Sixth Wisconsin Volunteers (1890, p. 169)

Despite this surrender, leaving Dawes standing awkwardly holding seven swords, the fighting continued for minutes more and numerous Confederates were able to escape back to Herr Ridge. The three Union regiments lost 390–440 of 1,184 engaged, but they had blunted Davis's attack, prevented them from striking the rear of the Iron Brigade, and so overwhelmed the Confederate brigade that it was unable to participate significantly in combat for the rest of the day. The Confederate losses were about 500 killed and wounded and over 200 prisoners out of 1,707 engaged.[22]

Midday lull

By 11:30 a.m., the battlefield was temporarily quiet. On the Confederate side, Henry Heth faced an embarrassing situation. He had been under orders from General Lee to avoid a general engagement until the full Army of Northern Virginia had concentrated in the area. But his excursion to Gettysburg, ostensibly to find shoes, was essentially a reconnaissance in force conducted by a full infantry division. This indeed had started a general engagement and Heth was on the losing side so far. By 12:30 p.m., his remaining two brigades, under Brig. Gen. J. Johnston Pettigrew and Col. John M. Brockenbrough, had arrived on the scene, as had the division (four brigades) of Maj. Gen. Dorsey Pender, also from Hill's Corps. Hill's remaining division (Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson) did not arrive until late in the day.[23]

Considerably more Confederate forces were on the way, however. Two divisions of the Second Corps, commanded by Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell, were approaching Gettysburg from the north, from the towns of Carlisle and York. The five brigades of Maj. Gen. Robert E. Rodes marched down the Carlisle Road but left it before reaching town to advance down the wooded crest of Oak Ridge, where they could link up with the left flank of Hill's Corps. The four brigades under Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early approached on the Harrisburg Road. Union cavalry outposts north of the town detected both movements. Ewell's remaining division (Maj. Gen. Edward "Allegheny" Johnson) did not arrive until late in the day.[24]

On the Union side, Doubleday reorganized his lines as more units of the I Corps arrived. First on hand was the Corps Artillery under Col. Charles S. Wainwright, followed by two brigades from Doubleday's division, now commanded by Brig. Gen. Thomas A. Rowley, which Doubleday placed on either end of his line. The XI Corps arrived from the south before noon, moving up the Taneytown and Emmitsburg Roads. Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard was surveying the area from the roof of the Fahnestock Brothers' dry-goods store downtown at about 11:30[25][lower-alpha 3] when he heard that Reynolds had been killed and that he was now in command of all Union forces on the field. He recalled: "My heart was heavy and the situation was grave indeed, but surely I did not hesitate a moment. God helping us, we will stay here till the Army comes. I assumed the command of the field."[27]

Howard immediately sent messengers to summon reinforcements from the III Corps (Maj. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles) and the XII Corps (Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum). Howard's first XI Corps division to arrive, under Maj. Gen. Carl Schurz, was sent north to take a position on Oak Ridge and link up with the right of the I Corps. (The division was commanded temporarily by Brig. Gen. Alexander Schimmelfennig while Schurz filled in for Howard as XI Corps commander.) The division of Brig. Gen. Francis C. Barlow was placed on Schurz's right to support him. The third division to arrive, under Brig. Gen. Adolph von Steinwehr, was placed on Cemetery Hill along with two batteries of artillery to hold the hill as a rallying point if the Union troops could not hold their positions; this placement on the hill corresponded with orders sent earlier in the day to Howard by Reynolds just before he was killed.[28]

However, Rodes beat Schurz to Oak Hill, so the XI Corps division was forced to take up positions in the broad plain north of the town, below and to the east of Oak Hill.[29] They linked up with the I Corps reserve division of Brig. Gen. John C. Robinson, whose two brigades had been sent forward by Doubleday when he heard about Ewell's arrival.[30] Howard's defensive line was not a particularly strong one in the north.[31] He was soon outnumbered (his XI Corps, still suffering the effects of their defeat at the Battle of Chancellorsville, had only 8,700 effectives), and the terrain his men occupied in the north was poorly selected for defense. He held out some hope that reinforcements from Slocum's XII Corps would arrive up the Baltimore Pike in time to make a difference.[32]

Afternoon

In the afternoon, there was fighting both west (Hill's Corps renewing their attacks on the I Corps) and north (Ewell's Corps attacking the I and XI Corps) of Gettysburg. Ewell, on Oak Hill with Rodes, saw Howard's troops deploying before him, and he interpreted this as the start of an attack and implicit permission to set aside Gen. Lee's order not to bring about a general engagement.[33]

Rodes attacks from Oak Hill

Rodes initially sent three brigades south against Union troops that represented the right flank of the I Corps and the left flank of the XI Corps: from east to west, Brig. Gen. George P. Doles, Col. Edward A. O'Neal, and Brig. Gen. Alfred Iverson. Doles's Georgia brigade stood guarding the flank, awaiting the arrival of Early's division. Both O'Neal's and Iverson's attacks fared poorly against the six veteran regiments in the brigade of Brig. Gen. Henry Baxter, manning a line in a shallow inverted V, facing north on the ridge behind the Mummasburg Road. O'Neal's men were sent forward without coordinating with Iverson on their flank and fell back under heavy fire from the I Corps troops.[34]

Iverson failed to perform even a rudimentary reconnaissance and sent his men forward blindly while he stayed in the rear (as had O'Neal, minutes earlier). More of Baxter's men were concealed in woods behind a stone wall and rose to fire withering volleys from less than 100 yards (91 m) away, creating over 800 casualties among the 1,350 North Carolinians. Stories are told about groups of dead bodies lying in almost parade-ground formations, heels of their boots perfectly aligned. (The bodies were later buried on the scene, and this area is today known as "Iverson's Pits", source of many local tales of supernatural phenomena.)[35]

Baxter's brigade was worn down and out of ammunition. At 3:00 p.m. he withdrew his brigade, and Gen. Robinson replaced it with the brigade of Brig. Gen. Gabriel R. Paul. Rodes then committed his two reserve brigades: Brig. Gens. Junius Daniel and Dodson Ramseur. Ramseur attacked first, but Paul's brigade held its crucial position. Paul had a bullet go in one temple and out the other, blinding him permanently (he survived the wound and lived 20 more years after the battle). Before the end of the day, three other commanders of that brigade were wounded.[36]

Daniel's North Carolina brigade then attempted to break the I Corps line to the southwest along the Chambersburg Pike. They ran into stiff resistance from Col. Roy Stone's Pennsylvania "Bucktail Brigade" in the same area around the railroad cut as the morning's battle. Fierce fighting eventually ground to a standstill.[37]

Heth renews his attack

Gen. Lee arrived on the battlefield at about 2:30 p.m., as Rodes's men were in mid-attack. Seeing that a major assault was underway, he lifted his restriction on a general engagement and gave permission to Hill to resume his attacks from the morning. First in line was Heth's division again, with two fresh brigades: Pettigrew's North Carolinians and Col. John M. Brockenbrough's Virginians.[38]

Pettigrew's Brigade was deployed in a line that extended south beyond the ground defended by the Iron Brigade. Enveloping the left flank of the 19th Indiana, Pettigrew's North Carolinians, the largest brigade in the army, drove back the Iron Brigade in some of the fiercest fighting of the war. The Iron Brigade was pushed out of the woods, made three temporary stands in the open ground to the east, but then had to fall back toward the Lutheran Theological Seminary. Gen. Meredith was downed with a head wound, made all the worse when his horse fell on him. To the left of the Iron Brigade was the brigade of Col. Chapman Biddle, defending open ground on McPherson Ridge, but they were outflanked and decimated. To the right, Stone's Bucktails, facing both west and north along the Chambersburg Pike, were attacked by both Brockenbrough and Daniel.[39]

Casualties were severe that afternoon. The 26th North Carolina (the largest regiment of the army with 839 men) lost heavily, leaving the first day's fight with around 212 men. Their commander, Colonel Henry K. Burgwyn, was fatally wounded by a bullet through his chest. By the end of the three-day battle, they had about 152 men standing, the highest casualty percentage for one battle of any regiment, North or South.[40] One of the Union regiments, the 24th Michigan, lost 399 of 496.[41] It had nine color bearers shot down, and its commander, Col. Henry A. Morrow, was wounded in the head and captured. The 151st Pennsylvania of Biddle's brigade lost 337 of 467.[42]

The highest ranking casualty of this engagement was Gen. Heth, who was struck by a bullet in the head. He was apparently saved because he had stuffed wads of paper into a new hat, which was otherwise too large for his head.[43] But there were two consequences to this glancing blow. Heth was unconscious for over 24 hours and had no further command involvement in the three-day battle. He was also unable to urge Pender's division to move forward and supplement his struggling assault. Pender was oddly passive during this phase of the battle; the typically more aggressive tendencies of a young general in Lee's army would have seen him move forward on his own accord. Hill shared the blame for failing to order him forward as well, but he claimed illness. History cannot know Pender's motivations; he was mortally wounded the next day and left no report.[44]

Early attacks XI Corps

Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard of the XI Corps had a difficult defensive problem. He had only two divisions (four brigades) to cover the wide expanse of featureless farmland north of town. He and Maj. Gen. Carl Schurz, temporarily in command of the corps while Howard was in overall command on the field, deployed the division of Brig. Gen. Alexander Schimmelfennig on the left and Brig. Gen. Francis C. Barlow on the right. From the left, the brigades were Schimmelfennig's (under Col. George von Amsberg), Col. Włodzimierz Krzyżanowski, Brig. Gen. Adelbert Ames, and Col. Leopold von Gilsa. Howard recalled that he selected this line as a logical continuation of the I Corps line formed on his left. This decision has been criticized by historians, such as Edwin B. Coddington, as being too far forward, with a right flank vulnerable to envelopment by the enemy. (Coddington suggests that a more defensible line would have been along Stevens Run, about 600 feet north of the railroad, a shorter line to defend, with better fields of fire, and with a more secure right flank.)[45]

Making the Federal defense more difficult, Barlow advanced farther north than Schimmelfennig's division, occupying a 50-foot (15 m) elevation above Rock Creek named Blocher's Knoll (known today as Barlow's Knoll).[46] Barlow's justification was that he wanted to prevent Doles's Brigade, of Rodes's division, from occupying it and using it as an artillery platform against him. General Schurz claimed afterward that Barlow had misunderstood his orders by taking this position. (In Schurz's official report, however, although he also states that Barlow misunderstood his order, he further states that Barlow "had been directing the movements of his troops with the most praiseworthy coolness and intrepidity, unmindful of the shower of bullets around," and "was severely wounded, and had to be carried off the battle-field."[47]) By taking the knoll, Barlow was following Howard's directive to obstruct the advance of Early's division, and in doing so, deprive him of an artillery platform, as von Steinwehr fortified the position on Cemetery Hill. The position on the knoll turned out to be unfortunate, as it created a salient in the line that could be assaulted from multiple sides. Schurz ordered Krzyżanowski's brigade, which had heretofore been sitting en masse at the north end of town (without further order to position from Schurz) forward to assist Barlow's two brigades on the knoll, but they arrived too late and in insufficient numbers to help. Historian Harry W. Pfanz judges Barlow's decision to be a "blunder" that "ensured the defeat of the corps."[48]

Richard Ewell's second division, under Jubal Early, swept down the Harrisburg Road, deployed in a battle line three brigades wide, almost a mile across (1,600 m) and almost half a mile (800 m) wider than the Union defensive line. Early started with a large-scale artillery bombardment. The Georgia brigade of Brigadier-General John B. Gordon was then directed for a frontal attack against Barlow's Knoll, pinning down the defenders, while the brigades of Brigadier-General Harry T. Hays and Colonel Isaac E. Avery swung around their exposed flank. At the same time the Georgians under Doles launched a synchronized assault with Gordon. The defenders of Barlow's Knoll targeted by Gordon were 900 men of von Gilsa's brigade; in May, two of his regiments had been the initial target of Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's flanking attack at Chancellorsville. The men of the 54th and 68th New York held out as long as they could, but they were overwhelmed. Then the 153rd Pennsylvania succumbed. Barlow, attempting to rally his troops, was shot in the side and captured. Barlow's second brigade, under Ames, came under attack by Doles and Gordon. Both Union brigades conducted a disorderly retreat to the south.[49]

The left flank of the XI Corps was held by Gen. Schimmelfennig's division. They were subjected to a deadly artillery crossfire from Rodes' and Early's batteries, and as they deployed they were attacked by Doles' infantry. Doles' and Early's troops were able to employ a flanking attack and roll up three brigade of the corps from the right, and they fell back in confusion toward the town. A desperate counterattack by the 157th New York from von Amsberg's brigade was surrounded on three sides, causing it to suffer 307 casualties (75%).[50]

Gen. Howard, witnessing this disaster, sent forward an artillery battery and an infantry brigade from von Steinwehr's reserve force, under Col. Charles Coster. Coster's battle line just north of the town in Kuhn's brickyard was overwhelmed by Hays and Avery. He provided valuable cover for the retreating soldiers, but at a high price: of Coster's 800 men, 313 were captured, as were two of the four guns from the battery.[51]

The collapse of the XI Corps was completed by 4 p.m., after a fight of less than an hour. They suffered 3,200 casualties (1,400 of them prisoners), about half the number sent forward from Cemetery Hill. The losses in Gordon's and Doles's brigades were under 750.[52]

Rodes and Pender break through

Rodes's original faulty attack at 2:00 had stalled, but he launched his reserve brigade, under Ramseur, against Paul's Brigade in the salient on the Mummasburg Road, with Doles's Brigade against the left flank of the XI Corps. Daniel's Brigade resumed its attack, now to the east against Baxter on Oak Ridge. This time Rodes was more successful, mostly because Early coordinated an attack on his flank.[53]

In the west, the Union troops had fallen back to the Seminary and built hasty breastworks running 600 yards (550 m) north-south before the western face of Schmucker Hall, bolstered by 20 guns of Wainwright's battalion. Dorsey Pender's division of Hill's Corps stepped through the exhausted lines of Heth's men at about 4:00 p.m. to finish off the I Corps survivors. The brigade of Brig. Gen. Alfred M. Scales attacked first, on the northern flank. His five regiments of 1,400 North Carolinians were virtually annihilated in one of the fiercest artillery barrages of the war, rivaling Pickett's Charge to come, but on a more concentrated scale. Twenty guns spaced only 5 yards (4.6 m) apart fired spherical case, explosive shells, canister, and double canister rounds into the approaching brigade, which emerged from the fight with only 500 men standing and a single lieutenant in command. Scales wrote afterwards that he found "only a squad here and there marked the place where regiments had rested."[54]

The attack continued in the southern-central area, where Col. Abner M. Perrin ordered his South Carolina brigade (four regiments of 1,500 men) to advance rapidly without pausing to fire. Perrin was prominently on horseback leading his men but miraculously was untouched. He directed his men to a weak point in the breastworks on the Union left, a 50-yard (46 m) gap between Biddle's left-hand regiment, the 121st Pennsylvania, and Gamble's cavalrymen, attempting to guard the flank. They broke through, enveloping the Union line and rolling it up to the north as Scales's men continued to pin down the right flank. By 4:30 p.m., the Union position was untenable, and the men could see the XI Corps retreating from the northern battle, pursued by masses of Confederates. Doubleday ordered a withdrawal east to Cemetery Hill.[55]

On the southern flank, the North Carolina brigade of Brig. Gen. James H. Lane contributed little to the assault; he was kept busy by a clash with Union cavalry on the Hagerstown Road. Brig. Gen. Edward L. Thomas's Georgia Brigade was in reserve well to the rear, not summoned by Pender or Hill to assist or exploit the breakthrough.[56]

Union retreat

The sequence of retreating units remains unclear. Each of the two corps cast blame on the other. There are three main versions of events extant. The first, most prevalent, version is that the fiasco on Barlow's Knoll triggered a collapse that ran counterclockwise around the line. The second is that both Barlow's line and the Seminary defense collapsed at about the same time. The third is that Robinson's division in the center gave way and that spread both left and right. Gen. Howard told Gen. Meade that his corps was forced to retreat only because the I Corps collapsed first on his flank, which may have reduced his embarrassment but was unappreciated by Doubleday and his men. (Doubleday's career was effectively ruined by Howard's story.)[60]

Union troops retreated in different states of order. The brigades on Seminary Ridge were said to move deliberately and slowly, keeping in control, although Col. Wainwright's artillery was not informed of the order to retreat and found themselves alone. When Wainwright realized his situation, he ordered his gun crews to withdraw at a walk, not wishing to panic the infantry and start a rout. As pressure eventually increased, Wainwright ordered his 17 remaining guns to gallop down Chambersburg Street, three abreast.[61] A.P. Hill failed to commit any of his reserves to the pursuit of the Seminary defenders, a great missed opportunity.[62]

Near the railroad cut, Daniel's Brigade renewed their assault, and almost 500 Union soldiers surrendered and were taken prisoner. Paul's Brigade, under attack by Ramseur, became seriously isolated and Gen. Robinson ordered it to withdraw. He ordered the 16th Maine to hold its position "at any cost" as a rear guard against the enemy pursuit. The regiment, commanded by Col. Charles Tilden, returned to the stone wall on the Mummasburg Road, and their fierce fire gave sufficient time for the rest of the brigade to escape, which they did, in considerably more disarray than those from the Seminary. The 16th Maine started the day with 298 men, but at the end of this holding action there were only 35 survivors.[63]

For the XI Corps, it was a sad reminder of their retreat at Chancellorsville in May. Under heavy pursuit by Hays and Avery, they clogged the streets of the town; no one in the corps had planned routes for this contingency. Hand-to-hand fighting broke out in various places. Parts of the corps conducted an organized fighting retreat, such as Coster's stand in the brickyard. The private citizens of Gettysburg panicked amidst the turmoil, and artillery shells bursting overhead and fleeing refugees added to the congestion. Some soldiers sought to avoid capture by hiding in basements and in fenced backyards. Gen. Alexander Schimmelfennig was one such person who climbed a fence and hid behind a woodpile in the kitchen garden of the Garlach family for the rest of the three-day battle.[64] The only advantage that the XI Corps soldiers had was that they were familiar with the route to Cemetery Hill, having passed through that way in the morning; many in the I Corps, including senior officers, did not know where the cemetery was.[65]

As the Union troops climbed Cemetery Hill, they encountered the determined Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock. At midday, Gen. Meade was nine miles (14 km) south of Gettysburg in Taneytown, Maryland, when he heard that Reynolds had been killed. He immediately dispatched Hancock, commander of the II Corps and his most trusted subordinate, to the scene with orders to take command of the field and to determine whether Gettysburg was an appropriate place for a major battle. (Meade's original plan had been to man a defensive line on Pipe Creek, a few miles south in Maryland. But the serious battle underway was making that a difficult option.)[66]

When Hancock arrived on Cemetery Hill, he met with Howard and they had a brief disagreement about Meade's command order. As the senior officer, Howard yielded only grudgingly to Hancock's direction. Although Hancock arrived after 4:00 p.m. and commanded no units on the field that day, he took control of the Union troops arriving on the hill and directed them to defensive positions with his "imperious and defiant" (and profane) persona. As to the choice of Gettysburg as the battlefield, Hancock told Howard "I think this the strongest position by nature upon which to fight a battle that I ever saw." When Howard agreed, Hancock concluded the discussion: "Very well, sir, I select this as the battle-field." Brig. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren, chief engineer of the Army of the Potomac, inspected the ground and concurred with Hancock.[67]

Evening

General Lee also understood the defensive potential to the Union army if they held the high ground of Cemetery Hill. He sent orders to Ewell to "carry the hill occupied by the enemy, if he found it practicable, but to avoid a general engagement until the arrival of the other divisions of the army." In the face of this discretionary, and possibly contradictory, order, Ewell chose not to attempt the assault.[68] One reason posited was the battle fatigue of his men in the late afternoon, although "Allegheny" Johnson's division of Ewell's Corps was within an hour of arriving on the battlefield. Another was the difficulty of assaulting the hill through the narrow corridors afforded by the streets of Gettysburg immediately to the north. Ewell requested assistance from A.P. Hill, but that general felt his corps was too depleted from the day's battle and General Lee did not want to bring up Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson's division from the reserve. Ewell did consider taking Culp's Hill, which would have made the Union position on Cemetery Hill untenable. However, Jubal Early opposed the idea when it was reported that Union troops (probably Slocum's XII Corps) were approaching on the York Pike, and he sent the brigades of John B. Gordon and Brig. Gen. William "Extra Billy" Smith to block that perceived threat; Early urged waiting for Johnson's division to take the hill. After Johnson's division arrived via the Chambersburg Pike, it maneuvered toward the east of town in preparation to take the hill, but a small reconnaissance party sent in advance encountered a picket line of the 7th Indiana Infantry, which opened fire and captured a Confederate officer and soldier. The remainder of the Confederates fled and attempts to seize Culp's Hill on July 1 came to an end.[69]

Responsibility for the failure of the Confederates to make an all-out assault on Cemetery Hill on July 1 must rest with Lee. If Ewell had been a Jackson he might have been able to regroup his forces quickly enough to attack within an hour after the Yankees had started to retreat through the town. The likelihood of success decreased rapidly after that time unless Lee were willing to risk everything.

Edwin B. Coddington, The Gettysburg Campaign[70]

Lee's order has been criticized because it left too much discretion to Ewell. Numerous historians and proponents of the Lost Cause movement (most prominently Jubal Early, despite his own reluctance to support an attack at the time) have speculated how the more aggressive Stonewall Jackson would have acted on this order if he had lived to command this wing of Lee's army, and how differently the second day of battle would have proceeded with Confederate artillery on Cemetery Hill, commanding the length of Cemetery Ridge and the Federal lines of communications on the Baltimore Pike.[71] Stephen W. Sears has suggested that Gen. Meade would have invoked his original plan for a defensive line on Pipe Creek and withdrawn the Army of the Potomac, although that movement would have been a dangerous operation under pressure from Lee.[72]

Most of the rest of both armies arrived that evening or early the next morning. Johnson's division joined Ewell and Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson's joined Hill. Two of the three divisions of the First Corps, commanded by Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, arrived in the morning. Three cavalry brigades under Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart were still out of the area, on a wide-ranging raid to the northeast. Gen. Lee sorely felt the loss of the "eyes and ears of the Army"; Stuart's absence had contributed to the accidental start of the battle that morning and left Lee unsure about enemy dispositions through most of July 2. On the Union side, Meade arrived after midnight. The II Corps and III Corps took up positions on Cemetery Ridge, and the XII Corps and the V Corps were nearby to the east. Only the VI Corps was a significant distance from the battlefield, marching rapidly to join the Army of the Potomac.[73]

The first day at Gettysburg—more significant than simply a prelude to the bloody second and third days—ranks as the 23rd-largest battle of the war by number of troops engaged. About one quarter of Meade's army (22,000 men) and one third of Lee's army (27,000) were engaged.[74] Union casualties were almost 9,000; Confederate slightly over 6,000.[75]

Notes

- ↑ Martin asserts that Buford was primarily concerned with the defense of the town itself, and while he had an innate understanding of the value of high ground, there is no evidence that he visited Cemetery Hill, Culp's Hill, or the Round Tops, or formally considered them as defensive ground for Meade's army.[2]

- ↑ Historians who address the matter disagree on whether any troopers in Buford's division, and especially in William Gamble's brigade, had repeating carbines or repeating rifles. It is a minority view and most historians present creditable arguments against it. In support of the minority view, Stephen D. Starr wrote that most of the troopers in flanking companies had Spencer carbines, which had arrived a few days before the battle.The Union Cavalry in the Civil War: From Fort Sumter to Gettysburg, 1861–1863. Volume 1, citing Buckeridge, J. O. Lincoln's Choice. Harrisburg, Stackpole Books, 1956, p. 55. Shelby Foote in Fredericksburg to Meridian, The Civil War: a Narrative, Volume 2 New York, 1963, ISBN 978-0-394-74621-0, p. 465, also stated that some Union troopers had Spencer carbines. Richard S. Shue also claimed that a limited distribution of Spencer rifles had been made to some of Buford's troopers in his book Morning at Willoughby Run Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 1995, ISBN 978-0-939631-74-2 p. 214.

Edward G. Longacre wrote that in Gamble's brigade "a few squadrons of Federal troopers used [Spencer] repeating rifles" (rather than carbines) but most had single-shot breech-loading carbines. Longacre p. 60. Order of battle at Coddington, p. 585. Coddington, pp. 258-259, wrote that men in the 5th Michigan and at least two companies of the 6th Michigan regiment had Spencer repeating rifles (rather than carbines). Harry Hansen wrote that Thomas C. Devin's brigade of one Pennsylvania and three New York regiments "were equipped with new Spencer repeating carbines," without reference to Gamble's men. The Civil War: A History. New York: Bonanza Books, 1961. OCLC 500488542, p. 370.

David G. Martin, in Gettysburg July 1 stated that all of Buford's men had single-shot breech-loading carbines which could be fired 5 to 8 times per minute, and fired from a prone position, as opposed to 2 to 3 rounds per minute with muzzle-loaders, "an advantage but not a spectacular one." p. 82. Cavalry historian Eric J. Wittenberg in The Devil's to Pay: John Buford at Gettysburg: A History and Walking Tour. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2014, 2015, 2018. ISBN 978-1-61121-444-4, stated that "while it is possible a handful of Spencer repeating rifles were present at Gettysburg" it is safe to conclude that Buford's troopers did not have them. He cited the fact that "only 64 percent of the companies in Gamble's and Devin's brigades filed their quarterly returns on June 30, 1863" in support of the possibility that some had repeaters but gave reasons for his rejection of that possibility. He dismissed Shelby Foote's statement as "mythology" because the Spencer carbines were not in mass production until September 1863, stated that Longacre credits Spencer repeating rifles to different regiments than the ordnance returns for the Army of the Potomac do, and discounted Shue's statement because he used "an unreliable source". pp. 209-210.

In their books on the battle or on the war as a whole, many historians have not commented directly on whether any Federal troopers had repeating carbines or rifle. Some of them, such as Harry Pfanz, First Day, p. 67 specifically mentioned that the Union cavalry had breech-loading carbines enabling the troopers to fire slightly faster than soldiers with muzzle-loading rifles and made no mention of repeaters. Similar statements to that of Pfanz are found at Keegan, p. 191; Sears, p. 163; Eicher, p. 510; Symonds, p. 71, Hoptak, p. 53, Trudeau, p. 164. Others such as McPherson and Guelzo do not mention the weapons used by Buford's division. - ↑ Pfanz estimates 10:30.[26]

- ↑ Historian W. Frassanito finds that these are photographs of the same group taken from different angles.[57]

- ↑ The site was tentatively identified in 2012.[58]

References

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, pp. 25–28; Martin, pp. 24, 29, 41.

- ↑ Martin pp. 47–48

- ↑ Sears, p. 155.

- ↑ Martin, pp. 43, 49; Pfanz, First Day, pp. 41–42.

- ↑ Martin, p. 60.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, pp. 52–56; Martin, pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Eicher, p. 510.

- ↑ Martin, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Martin, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, pp. 57, 59, 74; Martin, pp. 82–88, 96–97.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, p. 60; Martin, p. 103.

- ↑ Martin, pp. 102, 104.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, pp. 77–78; Martin, pp. 140–43.

- 1 2 Pfanz, Battle of Gettysburg, p. 13.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, pp. 81–90.

- ↑ Martin, pp. 149–61; Pfanz, First Day, pp. 91–98; Pfanz, Battle of Gettysburg, p. 13.

- ↑ Martin, pp. 160–61; Pfanz, First Day, pp. 100–101.

- ↑ Martin, p. 125.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, pp. 102–14.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, p. 112.

- ↑ Martin, p. 131.

- ↑ Martin, p. 140.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, pp. 117–19; Martin, pp. 186–89.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, pp. 148, 228; Martin, pp. 204–206.

- ↑ Martin, p. 198

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, p. 137

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, pp. 123, 124, 128, 137; Martin, p. 198.

- ↑ Martin, pp. 198–202; Pfanz, First Day, pp. 137, 140, 216.

- ↑ Pfanz, Battle of Gettysburg, p. 15.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, p. 130.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, p. 238.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, p. 158.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, pp. 161–62.

- ↑ Martin, pp. 205–210; Pfanz, First Day, pp. 163–66.

- ↑ Martin, pp. 224–38; Pfanz, First Day, pp. 170–78.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, pp. 182–84; Martin, pp. 247–55.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, pp. 194–213; Martin, pp. 238–47.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, pp. 275–76; Martin, p. 341.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, pp. 276–93; Martin, p. 342.

- ↑ Busey and Martin, pp. 298, 501.

- ↑ Busey and Martin, pp. 22, 386.

- ↑ Busey and Martin, pp. 27, 386.

- ↑ Martin, p. 366; Pfanz, First Day, p. 292.

- ↑ Martin, p. 395.

- ↑ Coddington, p. 301; Pfanz, First Day, pp. 218–23; Martin, p. 285.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, p. 217.

- ↑ Maj. Gen. Carl Schurz, Gettysburg Campaign, O.R. Series I, Volume XXVII/1 [S# 43].

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, pp. 230–31; Coddington, p. 301; Martin, pp. 276–77; Adkins, p. 379; Petruzzi and Stanley, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, pp. 229–48; Martin, pp. 277–91.

- ↑ Martin, p. 302; Pfanz, First Day, pp. 254–57.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, pp. 258–68; Martin, pp. 306–23.

- ↑ Sears, p. 217.

- ↑ Martin, pp. 386–93.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, pp. 305–11; Martin, pp. 394–404; Sears, p. 218.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, pp. 311–17; Martin, pp. 404–26.

- ↑ Martin, pp. 426–29; Pfanz, First Day, p. 302.

- ↑ Frassanito pp. 222–229

- ↑ "Gettysburg Harvest of death Photo location". civilwartalk.com. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ↑ Frassanito pp.70–71

- ↑ Sears, p. 224.

- ↑ Sears, p. 220; Martin, p. 446.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, p. 320; Sears, p. 223.

- ↑ Martin, pp. 379, 389–92.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, pp. 328–29.

- ↑ Martin, p. 333.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, pp. 337–38; Sears, pp. 223–25.

- ↑ Martin, pp. 482–88.

- ↑ Sears, p. 227; Martin, p. 504; Mackowski and White, p. 35.

- ↑ Mackowski and White, pp. 36–41; Bearss, pp. 171–72; Coddington, pp. 317–21; Gottfried, p. 549; Pfanz, First Day, pp. 347–49; Martin, p. 510.

- ↑ Coddington, pp. 320–21.

- ↑ See, for instance, Pfanz, First Day, pp. 345–46, or Martin, pp. 563–65.

- ↑ Sears, pp. 233–34.

- ↑ Eicher, p. 520; Martin, p. 537.

- ↑ Martin, p. 9, citing Thomas L. Livermore's Numbers & Losses in the Civil War in America (Houghton Mifflin, 1900).

- ↑ Trudeau, p. 272.

Sources

- Adkin, Mark. The Gettysburg Companion: The Complete Guide to America's Most Famous Battle. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2008. ISBN 978-0-8117-0439-7.

- Bearss, Edwin C. Fields of Honor: Pivotal Battles of the Civil War. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society, 2006. ISBN 0-7922-7568-3.

- Busey, John W., and David G. Martin. Regimental Strengths and Losses at Gettysburg. 4th ed. Hightstown, NJ: Longstreet House, 2005. ISBN 0-944413-67-6.

- Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign; a study in command. New York: Scribner's, 1968. ISBN 0-684-84569-5.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Frassanito, W. (1975). Gettysburg A Journey in Time. Thomas Publications. ISBN 0939631970.

- Gottfried, Bradley M. Brigades of Gettysburg. New York: Da Capo Press, 2002. ISBN 0-306-81175-8.

- Longacre, Edward G. The Cavalry at Gettysburg: A Tactical Study of Mounted Operations during the Civil War's Pivotal Campaign, 9 June–14 July, 1863. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986. ISBN 978-0-8032-7941-4.

- Longacre, Edward G. General John Buford: A Military Biography. Conshohocken, PA: Combined Publishing, 1995. ISBN 978-0-938289-46-3.

- Mackowski, Chris, and Kristopher D. White. "Second Guessing Dick Ewell: Why Didn't the Confederate General Take Cemetery Hill on July 1, 1863?" Civil War Times, August 2010.

- Martin, David G. Gettysburg July 1. rev. ed. Conshohocken, PA: Combined Publishing, 1996. ISBN 0-938289-81-0.

- Petruzzi, J. David, and Steven Stanley. The Complete Gettysburg Guide. New York: Savas Beatie, 2009. ISBN 978-1-932714-63-0.

- Pfanz, Harry W. The Battle of Gettysburg. National Park Service Civil War series. Fort Washington, PA: U.S. National Park Service and Eastern National, 1994. ISBN 0-915992-63-9.

- Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg – The First Day. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8078-2624-3.

- Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003. ISBN 0-395-86761-4.

- Trudeau, Noah Andre. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage. New York: HarperCollins, 2002. ISBN 0-06-019363-8.

Further reading

- Bearss, Edwin C. Receding Tide: Vicksburg and Gettysburg: The Campaigns That Changed the Civil War. Washington DC: National Geographic Society, 2010. ISBN 978-1-4262-0510-1.

- Catton, Bruce. Glory Road. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1952. ISBN 0-385-04167-5.

- Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative. Vol. 2, Fredericksburg to Meridian. New York: Random House, 1958. ISBN 0-394-49517-9.

- Freeman, Douglas S. Lee's Lieutenants: A Study in Command. 3 vols. New York: Scribner, 1946. ISBN 0-684-85979-3.

- Freeman, Douglas S. R. E. Lee, A Biography. 4 vols. New York: Scribner, 1934.

- Gottfried, Bradley M. The Maps of Gettysburg: An Atlas of the Gettysburg Campaign, June 3 – 13, 1863. New York: Savas Beatie, 2007. ISBN 978-1-932714-30-2.

- Grimsley, Mark, and Brooks D. Simpson. Gettysburg: A Battlefield Guide. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8032-7077-1.

- Hall, Jeffrey C. The Stand of the U.S. Army at Gettysburg. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-253-34258-9.

- Laino, Philip. Gettysburg Campaign Atlas. 3rd ed. Gettysburg, PA: Gettysburg Publishing, 2009. ISBN 978-0-983-8631-4-4. First published in 2009 by Gatehouse Press.

- Mackowski, Chris, Kristopher D. White, and Daniel T. Davis. Fight Like the Devil: The First Day at Gettysburg, July 1, 1863. Emerging Civil War Series. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2015. ISBN 978-1-61121-227-3.

- Teague, Chaplain Chuck. "Barlow's Knoll Revisited", Military History Online website, accessed July 9, 2013.

External links

- Flags of the First Day: An Online Exhibit of Iron Brigade and Confederate battle flags from July 1, 1863 Archived March 16, 2011, at the Wayback Machine: (Civil War Trust)

- "No Man Can Take Those Colors and Live: The Epic Battle Between the 24th Michigan and 26th North Carolina at Gettysburg: (Civil War Trust)