| Battle of Gela (405 BC) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of The Sicilian Wars | |||||||||

Sandy stretch of coast in the Manfria district, near Gela (in the background) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Gela Syracuse | Carthage | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Dionysius I of Syracuse Leptines of Syracuse | Himilco Hanno | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| estimated 30,000 - 40,000[1] | estimated 30,000 - 40,000 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 1,600 | Unknown | ||||||||

The Battle of Gela took place in the summer of 405 BC in Sicily. The Carthaginian army under Himilco (a member of the Magonid family and kinsman of Hannibal Mago), which had spent the winter and spring in the captured city of Akragas, marched to confront the Greeks at Gela. The Syracuse government had deposed Daphnaeus, the unsuccessful general of the Greek army at Akragas, with Dionysius, another officer who had been a follower of Hermocrates. Dionysius schemed and gained full dictatorial powers.

When the Carthaginians laid siege to Gela, Dionysius responded by leading his forces from Syracuse to confront the threat. He devised a complex three-pronged attack strategy against the Carthaginians, but the plan failed due to a lack of proper coordination. Faced with the defeat and growing discontent in Syracuse, Dionysius made the decision to evacuate Gela to preserve his own power. After the Greeks had fled to Camarina Himilco, the Carthaginian general, sacked the abandoned city.

Background

Carthage had stayed away from Sicilian affairs for almost 70 years following the defeat at Himera in 480, during which time Greek culture had started to penetrate the Elymian, Sikanian and Sicel cities in Sicily. This all changed in 411 when the Elymian city Segesta was defeated by the Dorian Greek city Selinus. Segesta appealed to Carthage for aid, and the Carthaginian Senate agreed to intervene on behalf of Segesta. Hannibal Mago of Carthage led an army which took the city of Selinus by storm in 409 and then also destroyed the city of Himera. Syracuse and Akragas, the leading Greek cities in Sicily did not confront Carthage at that time and the Carthaginian army withdrew with the spoils of war.[2] For three years, a lull fell on Sicily. No treaties had been signed between the Greeks and Carthaginians signaling a closure of hostilities.

The expedition of 406 BC

The raids of the exiled Syracusan general, Hermocrates, on Punic territory around Motya and Panormus provoked Carthage into sending another army to Sicily in 406 under Hannibal Mago.[3] The leading Greek cities of Sicily, Syracuse and Akragas, had prepared for the conflict by hiring mercenaries and expanding the fleet, along with keeping the city walls in good repair. Although Syracuse was involved in the Peloponnesian War and with disputes with her neighbors, their government sent an appeal for support to Magna Graecia and mainland Greece once the Carthaginians landed in Sicily.

Hannibal besieged Akragas in summer 406, which withstood the initial assault. While building siege ramps for future attacks the army was struck by plague and Hannibal along with thousands of Carthaginians perished. Part of the Carthaginian army under Himilco, Hannibal’s kinsmen and deputy, was defeated by the Greek relief army led by Daphnaeus, and the city was relieved. The Akragans were not happy with the decision of the generals (who refrained from chasing the defeated Carthaginians) and had four of them stoned to death. The Greeks then cut off supplies to the Carthaginian camp and almost caused a mutiny in the Punic army. Himilco saved the situation by managing to defeat the Syracusan fleet and capturing the grain convoy bound for Akragas. The Greeks, faced with starvation, abandoned Akragas, which was sacked by Himilco. The siege had lasted for eight months.[4]

A tyrant rises

The homeless people from Akragas arrived at Syracuse and some made accusations against the Syracusan generals. In the assembly, Dionysius, who had fought bravely at Akragas, supported these accusations. He was fined for breaking meeting rules, but his friend Philistos paid the fine. The assembly deposed Daphnaeus and the other generals and appointed replacements, Dionysius among them. The Akragan refugees ultimately found shelter in Leontini. An appeal from Gela then reached Syracuse to send aid, as the Carthaginians were approaching that city.[5]

Dionysius started scheming to expand his power. He got the government to recall political exiles who were former followers of Hermocrates, and then marched to Gela, which was under the command of the Spartan Dexippus. Dionysius dabbled in the political feud of Gela and managed to condemn their generals to death. He gave his soldier double pay from the confiscated property of the dead generals, then returned to Syracuse to accuse his fellow generals of taking bribes from Carthage. The Syracusan government deposed the others and made Dionysius sole commander. Dionysius marched to Leontini, held an assembly, and after some stage-managed theatrics, promptly got the people to give him a bodyguard of 600 men, which he increased to 1,000. Then he sent Dexippus away and had Daphnaeus and other Syracusan generals executed. The tyranny of Dionysius had begun.[5]

Opposing forces

Hannibal Mago had brought together an army recruited from Carthaginian citizens, Africa, Spain and Italy, and a fleet of 120 triremes to Sicily. The army had been reduced by plague and casualties at Akragas and it is not known if Himilco had received any reinforcements or recruits while he wintered at Akragas. The original forces may have numbered around 60,000 men,[6] and the survivors marched to Gela in the spring of 405. The Carthaginian fleet, which numbered around 105 ships after losing 15 triremes at Eryx to the Greeks fleet under Leptines,[7] was at Motya and did not accompany the army.

Carthaginian cohorts

The Libyans supplied both heavy and light infantry and formed the most disciplined units of the army. African heavy infantry fought in close formation, armed with long spears and round shields, wearing helmets and linen cuirasses. Light Libyan infantry carried javelins and a small shield, same as the Iberian light infantry. The Iberian infantry wore purple-bordered white tunics and leather headgear. The heavy infantry fought in a dense phalanx, armed with heavy throwing spears, long body shields, and short thrusting swords.[8] Campanian (probably equipped like Samnite or Etruscan warriors),[9] Sicel, Sardinian and Gallic infantry fought in their native gear,[10] but often were equipped by Carthage. Sicels and other Sicilians were equipped like Greek Hoplites.

The Libyans, Carthaginian citizens, and the Libyo-Phoenicians provided disciplined, well-trained cavalry equipped with thrusting spears and round shields. Numidia provided superb light cavalry armed with bundles of javelins and riding without bridle or saddle. Iberians and Gauls also provided cavalry, which relied on the all-out charge. Carthage at this time did not use elephants, but Libyans provided the bulk of the heavy, four horse war chariots for Carthage,[11] which is not mentioned being present at Gela. The Carthaginian officer corps held overall command of the army, although many units may have fought under their chieftains.

The Punic navy was built around the trireme, Carthaginian citizens usually served alongside recruits from Libya and other Carthaginian domains.

Greek forces

Large Sicilian cities like Syracuse and Akragas could field up to 10,000–20,000 citizens,[12] while smaller ones like Himera and Messana mustered between 3,000[13]–6,000[14] soldiers. Gela probably could field similar numbers. Dionysius brought 30,000 foot and 1,000 horsemen, recruited from Syracuse, allied Sicilian Greek cities, and mercenaries along with 50 triremes to Gela in 405.

The mainstay of the Greek army was the hoplite, drawn mainly from the citizens by Dionysius, and had a large number of mercenaries from Italy and Greece as well. Sicels and other native Sicilians also served in the army as hoplites and also supplied peltasts, and a number of Campanians,[15] probably equipped like Samnite or Etruscan warriors,[9] were present as well. The Phalanx was the standard fighting formation of the army. The cavalry was recruited from wealthier citizens and hired mercenaries They were augmented by mercenary hoplites hired from Sicily and Italy and even mainland Greece. Some of the citizens also served as peltasts while the wealthier citizens formed the cavalry units. Sicels and Sikan soldiers also served in the force. Mercenaries provided archers, slingers, and cavalry.

Gela under threat

While Dionysius was busy with scheming his way to absolute power, the Carthaginian army had left their winter base at Akragas after destroying the city. Himilco marched along the coast to Gela, and set up camp near the sea on the west of the city, fortifying it with a trench and palisade. The Carthaginians spent some time plundering the countryside and gathering provisions prior to commencing siege operations. The Gelans had proposed removing their women and children to Syracuse, but the women insisted on staying put. Finally no one was forced to evacuate the city, and the Greeks kept up an active defense by harassing the Carthaginian foragers.[16]

Assault on Gela

Himilco resolved on storming the city before any help arrived. The Carthaginians did not bother to build circumvallation walls around Gela, they decided on direct assault. Despite Gelan resistance, the Carthaginians managed to move battering rams up to the western walls of the city and make some breaches in them. However, the defenders managed to keep the attackers at bay all day and repaired the walls at night. The help of the women in repairing the walls was invaluable. The Carthaginians had to start from the beginning the following morning.[17]

Siege relieved

Apart from his political machinations, Dionysius had managed to make ready an army made of Italian and Sicilian Greeks and mercenaries, numbering at least 30,000 hoplites and 4,000 cavalry and a fleet of 50 triremes,[18] and had marched at a slow pace to Gela. The arrival of this army lifted the Punic siege for the time being. The Greeks encamped at the mouth of River Gela on the western bank beside the city opposite the Carthaginian camp, close enough to the sea to direct both land and naval operations.[16]

Prelude to battle

For three weeks Dionysius harassed the Carthaginians with light troops and cut off their supplies using his fleet. These tactics had almost brought disaster for the Carthaginians at Akragas, but it is likely that Dionysius chose to fight a pitched battle after three weeks because of the mood of his soldiers against a war of attrition. The Carthaginian army probably outnumbered the combined Greek force and Dionysius resolved to use stratagem to neutralize this enemy advantage.[19]

Pulling a Cannae on Carthage

One hundred and eighty-nine years after the events at Gela, Hannibal destroyed a large Roman army near a Roman supply depot in Apulia using perhaps the best-known example of the double envelopement maneuver. Dionysius almost pulled one off on the Carthaginains at Gela in 405, but given the difference in circumstances that existed at Cannae and Gela, the battle plan of Hannibal and Dionysius varied; and like Hannibal’s brother Hasdrubal Barca found at the Battle of Dertosa in 215, a field commander needs a certain amount of luck along with skilled subordinates and disciplined soldiers to coordinate the complexities of the maneuver correctly.

The Greek battle plan

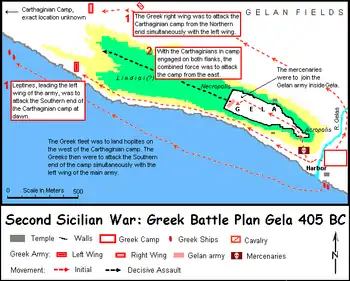

The Carthaginians were camped to the west of Gela and Dionysius planned a three-pronged attack[20] that had to follow a precise timetable. The Carthaginian cavalry was posted on the landward side while the mercenaries were on the seaward side, with the Africans in between inside the camp. Dionysius, observing that a seaborne force could attack the camp from the south, where it was open and lightly defended, decided on the following course:

- A group of a few thousand light troops would land on the beach south of the Carthaginian camp under the command of his brother Leptines and attack the south end of the camp from the west, occupying the Carthaginian forces, while 4,000 Italian hoplites would march along the coast and attack the south end of the camp from the east. At the same time, the Greek cavalry, supported by 8,000 hoplites would engage the Carthaginians on the northern side of the camp.

- Dionysius, with the reserve force and Gelan hoplites, would sally out from the West gate of the city and attack the camp once the Carthaginians were fully committed on the flanks of their camp.[21]

Difference with Hannibal’s plan at Cannae

The armies and terrain, as well as the circumstances at Cannae, differed greatly from those at Gela and the battle plans of Hannibal and Dionysius reflected this:

- Hannibal planned to fight the Romans outside their camp while Dionysius planned to attack the Carthaginians within their camp.

- Hannibal devised an unusual infantry formation to envelop the Roman infantry. He pushed the Carthaginian center forward, when the Roman infantry attacked and drove back the Carthaginians, Hannibal’s infantry posted at the end of the center attacked the exposed Roman flank and achieved a double envelopment. Dionysius formed no special formation, nor did the Greek center start the battle at Gela. The Greek troops were to attack the Carthaginian camp simultaneously from both sides and achieve a double envelopment before their center would get involved.

- The Carthaginian heavy cavalry was to play a special part in dispersing the Roman cavalry, then attacking the Roman infantry from the rear. Dionysius planned only a supporting role for the Greek cavalry at Gela.

Battle

The plan depended on precise coordination between the three Greek detachments, or risked a defeat in detail for the Greeks. As things turned out, coordination was horrible: the sea-borne troops under Leptines achieved total surprise and together with the hoplites attacking along the coast broke into the Carthaginian camp. While this group fought with the Campanians and Iberians,[22] the northern group was slow in arriving and did not launch their attack in time. This gave the Carthaginians time to first defeat the Greeks attacking in the south, where Leptines lost 1,000 men before giving way. The Carthaginians gave chase to the retreating Greeks, but Greek ships poured missiles on the advancing Carthaginians,[23] which allowed the fleeing Greeks to reach Gela safely. Some of the Gelan soldiers aided the Greeks, but most held back because they feared leaving the city walls undefended.

The northern Greek detachment meanwhile attacked the camp and drove back the Africans, who had come out to oppose them. At this juncture Himilco and the Carthaginian citizens[24] counterattacked, and the Campanians and Iberians also came up, routing the northern prong of the attack, with the loss of another 600 Greeks. The force under Dionysius got entangled in the narrow streets of the city amid the population and never attacked. The Greek cavalry was never engaged and the Carthaginians chased the Greeks back to the city. After the fighting ceased, Himilco had won the day.

While the Greek army was far from beaten, its morale had suffered and Dionysius faced political unrest in Syracuse. The army may have been unwilling to resume the harassing campaign,[25] and if the Greeks garrisoned in Gela had been bottled up by the Carthaginians, political enemies of Dionysius might take the chance to stage a coup in Syracuse. Dionysius chose to evacuate Gela and requested a truce to bury the dead. However, he instead slipped out that very night with most of his army and the population of Gela, leaving the battle dead unburied. A group of 2,000 light troops stayed behind, where they lit large campfires to dupe the Carthaginians into thinking the Greeks were staying put. The next morning, these troops also marched from Gela. The Carthaginians entered and sacked the near-empty city the following day.[26]

Aftermath

Dionysius led the army to Camarina, where he ordered the population to leave town. The strategic problem for Dionysius had not changed, getting stuck in a siege at Camarina might still mean risking political disaster in Syracuse. The march to Syracuse was slow. Suspicion arose among the Syracusan citizens that Dionysius might be in league with Himilco, and a coup attempt was launched. The spoils of Gela included a famous statue of Apollo, which was sent to Tyre.[27]

Syracuse discontent

Some of the cavalry, made up of rich former oligarchs, rode in haste to Syracuse and tried to take control of the city. Their attempt was clumsy, as Dionysius arriving at Syracuse found the gates shut but unguarded. He burnt down the gate and killed most of the rebels, while some of them managed to get away and seize the Sicel town of Aetna. The refugees of Gela and Camarina, distrustful of Dionysius, joined the Akragan refugees at Leontini. The position of Dionysius was hardly secure, as Himilco and his army, after taking and sacking Camarina, were marching for Syracuse.[28]

Peace of 405

Instead of a Carthaginian assault on Syracuse, a peace treaty was signed between the belligerents in 405. Reasons for the treaty are speculated as:

- Dionysius was indeed in communication with Himilco and agreed to a treaty favorable to Carthage in exchange for peace and recognition of his authority.[29] This is highly probable based on the future events in the career of Dionysius.

- The army of Himilco was struck by plague again. During the entire campaign, the army had lost almost half its strength to the plague.[30] Himilco chose not to battle Syracuse in his weakened state and opted for the treaty, which mostly favored Carthage.

- Unlike the Roman Republic, which always fought to achieve a favorable outcome,[31] with treaties seen as temporary interludes, the Carthaginians were mostly willing to negotiate and abide by treaties as long as their commercial infrastructure was intact. Carthage had kept to the terms of the treaty after the Battle of Himera in 480 for 70 years. In 149, Carthage continually submitted to the ever harsher and insulting demands of the Roman consuls until they demanded Carthaginians to move to an inland location, ending all their commercial activities. Only then did the Carthaginians renege on the treaty.

The terms of the treaty were:[32]

- Carthage keeps full control of the Phoenician cities in Sicily. Elymian and Sikan cities were in the Carthaginian sphere of influence.

- Greeks were allowed to return to Selinus, Akragas, Camarina and Gela. These cities, including the new city of Thermae, would pay tribute to Carthage. Gela and Camarina were forbidden to repair their walls.

- The Sicels and the city of Messene were to remain free of Carthaginian and Syracusan influence, as was Leontini.

- Dionysius was acknowledged as ruler of Syracuse by Carthage.

- Both sides agreed to release prisoners and ships captured during the campaign.

The Carthaginian army and fleet left Sicily after the treaty. The plague was carried back to Africa, where it ravaged Carthage. Himilco was elected as "king" by 398. He would lead the Carthaginian response to the activities of Dionysius in 398. The treaty was to last until 404 when Dionysius started a war against the Sicels. As Carthage took no action, Dionysius increased his power and domain in Sicily and finally in 398 launched a war against the Carthaginians by attacking Motya.

References

- ↑ Kern, Paul B., Ancient Greek Warfare, p172

- ↑ Bath, Tony, Hannibal's Campaigns, p. 11

- ↑ Freeman, Edward A., Sicily, pp. 145-47

- ↑ Kern, Paul B., Ancient Siege Warfare, pp. 163-170

- 1 2 Freeman, Edward A., Sicily, pp. 151-52

- ↑ Caven, Brian, Dionysius I: Warlord of Sicily, pp. 45-46

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus, XIII.80

- ↑ Goldsworthy, Adrian, The fall of Carthage, p. 32 ISBN 0-253-33546-9

- 1 2 Warry, John. Warfare in the Classical World. p. 103

- ↑ Makroe, Glenn E., Phoenicians, pp. 84-86 ISBN 0-520-22614-3

- ↑ Warry, John. Warfare in the Classical World. pp. 98-99

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus, X.III.84

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus, X.IV.40

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus XIII.60

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus, XIII.80.4

- 1 2 Kern, Paul B., Ancient Siege Warfare, p. 172

- ↑ Kern, Paul B., Ancient Siege Warfare, pp. 172-73

- ↑ Caven, Brian, Dionysius I, p. 62

- ↑ Kern, Paul B., Ancient Siege Warfare, p. 173

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus, XIII.109.4

- ↑ Caven, Brian, Dionysius I, pp. 63-72

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus, XIII.110.5

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus, XIII.110.6

- ↑ Diodurus Siculus XIII.110

- ↑ Caven, Brian, Dionysius I, p. 63

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus 13.111.1-2

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus 13.112-113

- ↑ Freeman, Edward A., Sicily, pp. 153-54

- ↑ Freeman, Edward A., Sicily, p. 154

- ↑ Church, Alfred J., Carthage, p. 44

- ↑ Goldsworthy, Adrian, Roman Warfare, p. 85

- ↑ Church, Alfred J., Carthage, pp. 44-45

Sources

- Baker, G. P. (1999). Hannibal. Cooper Square Press. ISBN 0-8154-1005-0.

- Bath, Tony (1992). Hannibal's Campaigns. Barns & Noble. ISBN 0-88029-817-0.

- Church, Alfred J. (1886). Carthage (4th ed.). T. Fisher Unwin.

- Freeman, Edward A. (1892). Sicily: Phoenician, Greek & Roman (3rd ed.). T. Fisher Unwin.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2007). Roman Warfare. Orion Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-7538-2258-6.

- Kern, Paul B. (1999). Ancient Siege Warfare. Indiana University Publishers. ISBN 0-253-33546-9.

- Lancel, Serge (1997). Carthage: A History. Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 1-57718-103-4.

- Warry, John (1993) [1980]. Warfare in The Classical World: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of Weapons, Warriors and Warfare in the Ancient Civilisations of Greece and Rome. New York: Barnes & Noble. ISBN 1-56619-463-6.

External links

- Diodorus Siculus translated by G. Booth (1814) Complete book (scanned by Google)

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1870). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1870). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)