| Battle of Friedland | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Fourth Coalition | |||||||

Napoleon at the Battle of Friedland (1807). The Emperor is depicted giving instructions to General Nicolas Oudinot. Between them is depicted General Etienne de Nansouty and behind the Emperor, on his right is Marshal Michel Ney. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

80,000 (65,000 engaged[2]) 118 cannons[3][4][5][6][7][8][9] |

46,000–60,000 120 cannons[3][4][6][7][8] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 8,000[10]–10,000[11] |

20,000[10]–40,000[12] killed, wounded and captured 80 guns[10] | ||||||

Location within Europe | |||||||

The Battle of Friedland (14 June 1807) was a major engagement of the Napoleonic Wars between the armies of the French Empire commanded by Napoleon I and the armies of the Russian Empire led by Count von Bennigsen. Napoleon and the French obtained a decisive victory that routed much of the Russian army, which retreated chaotically over the Alle River by the end of the fighting. The battlefield is located in modern-day Kaliningrad Oblast, near the town of Pravdinsk, Russia.

The engagement at Friedland was a strategic necessity after the Battle of Eylau earlier in 1807 had failed to yield a decisive verdict for either side. The battle began when Bennigsen noticed the seemingly isolated reserve corps of Marshal Lannes at the town of Friedland. Bennigsen, who planned only to secure his march northward to Wehlau and never intended to risk an engagement against Napoleon's numerically-superior forces, thought he had a good chance of destroying these isolated French units before Napoleon could save them, and ordered his entire army over the Alle River.[13] Lannes skillfully held his ground against determined Russian attacks until Napoleon could bring additional forces onto the field. Bennigsen could have recalled the Russian forces, numbering about 50,000–60,000 men on the opposite bank of the river, and retreated across the river before the arrival of Napoleon's entire army but, being in poor health, decided to stay at Friedland and took no measures to protect his exposed and exhausted army.[13] By late afternoon, the French had amassed a force of 80,000 troops close to the battlefield. Relying on superior numbers and the vulnerability of the Russians with their backs to the river, Napoleon concluded that the moment had come and ordered a massive assault against the Russian left flank. The sustained French attack pushed back the Russian army and pressed them against the river behind. Unable to withstand the pressure, the Russians broke and started escaping across the Alle, where an unknown number of them died from drowning.[14] The Russian army suffered horrific casualties at Friedland–losing over 40% of its soldiers on the battlefield.[15]

Napoleon's overwhelming victory was enough to convince the Russian political establishment that peace was necessary. Friedland effectively ended the War of the Fourth Coalition, as Emperor Alexander I reluctantly entered peace negotiations with Napoleon. These discussions eventually culminated in the Treaties of Tilsit, by which Russia agreed to join the Continental System against Great Britain and by which Prussia lost almost half of its territories. The lands lost by Prussia were converted into the new Kingdom of Westphalia, which was governed by Napoleon's brother, Jérôme. Tilsit also gave France control of the Ionian Islands, a vital and strategic entry point into the Mediterranean Sea. Some historians regard the political settlements at Tilsit as the height of Napoleon's empire because there was no longer any continental power challenging the French domination of Europe.[16]

Prelude

Prior to Friedland, Europe had become embroiled in the War of the Third Coalition in 1805. Following the French victory at the Battle of Austerlitz in December 1805, Prussia went to war in 1806 to recover her position as the leading power of Central Europe.

The Prussian Campaign

Franco-Prussian tensions gradually increased after Austerlitz. Napoleon insisted that Prussia should join his economic blockade of Great Britain. This adversely affected the German merchant class. Napoleon ordered a raid to seize a subversive, anti-Napoleonic bookseller named Johann Philipp Palm in August 1806, and made a final attempt to secure terms with Britain by offering her Hanover, which infuriated Prussia.[17] The Prussians began to mobilize on 9 August 1806 and issued an ultimatum on 26 August: they required French troops to withdraw to the west bank of the Rhine by 8 October on pain of war between the two nations.[18]

Napoleon aimed to win the war by destroying the Prussian armies before the Russians could arrive.[18] 180,000 French troops began to cross the Franconian forest on 2 October 1806, deployed in a bataillon-carré (square-battalion) system designed to meet threats from any possible direction.[19] On 14 October the French won decisively at the large double-battle of Jena-Auerstedt. A famous pursuit followed, and by the end of the campaign the Prussians had lost 25,000 killed and wounded, 140,000 prisoners, and more than 2,000 cannon.[20] A few Prussian units managed to cross the Oder River into Poland, but Prussia lost the vast majority of its army. Russia now had to face France alone. By 18 November French forces under Louis Nicolas Davout were marching from Eylau, and towards Warsaw with their spirits high. Augereau's men had neared Bromberg, and Jérôme Bonaparte's troops had reached the approaches of Kalisz.[21]

Eylau

When the French arrived in Poland, the local people hailed them as liberators.[22] The Russian general Bennigsen worried that French forces might cut him off from Buxhoevden's army, so he abandoned Warsaw and retreated to the right bank of the Vistula. On 28 November 1806 French troops under Murat entered Warsaw. The French pursued the fleeing Russians and a significant battle developed around Pułtusk on 26 December. The result remained in doubt, but Bennigsen wrote to the Tsar that he had defeated 60,000 French troops, and as a result he gained overall command of the Russian armies in Poland. At this point, Marshal Ney began to extend his forces to procure food supplies. Bennigsen noticed a good opportunity to strike at an isolated French corps, but he abandoned his plans once he realized Napoléon's maneuvers intended to trap his army.[23] The Russians withdrew towards Allenstein (Battle of Allenstein, 3 February), and later to Eylau.

On 7 February the Russians fought Soult's corps for possession of Eylau. Daybreak on 8 February saw 44,500 French troops on the field against 67,000 Russians,[23] but after receiving reinforcements the French had 75,000 men against 76,000.[24][25] Napoleon hoped to pin Bennigsen's army long enough to allow Ney's and Davout's troops to outflank the Russians. A fierce struggle ensued, made worse by a blinding snowstorm on the battlefield. The French found themselves in dire straits until a massed cavalry charge, made by 10,700 troopers formed in 80 squadrons,[26] relieved the pressure on the centre. Davout's arrival meant the attack on the Russian left could commence, but the assault was blunted when a Prussian force under L'Estocq suddenly appeared on the battlefield and, with Russian help, threw the French back. Ney came too late to effect any meaningful decision, so Bennigsen retreated. Casualties at this indecisive battle were horrific, perhaps 25,000 on each side.[27] More importantly, however, the lack of a decisive victory by either side meant that the war would go on.

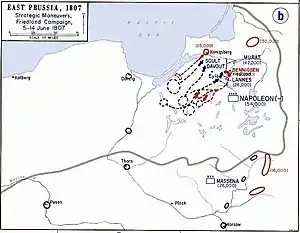

Heilsberg

After several months of recuperating from Eylau, Napoleon ordered the Grande Armée on the move once again. Learning that the Russians had encamped at their operational base in the town of Heilsberg, by the Alle River, Napoleon decided to conduct a general assault in the hopes of dislodging what he thought was the rearguard of the Russian army. In fact, the French ran into the entire Russian army of over 50,000 men and 150 artillery guns.[28] Repeated and determined attacks by the French failed to dislocate the Russians, who were fighting inside elaborate earthworks designed to prevent precisely the kind of river crossing Napoleon was attempting. French casualties soared to 10,000 while the Russians lost about 6,000.[28] The Russians eventually withdrew from Heilsberg as their position became untenable, prompting Napoleon to chase after them once again. The French headed in the direction of Königsberg to gain additional supplies and provisions. On 13 June the advance guard of Marshal Lannes reported seeing large numbers of Russian troops at the town of Friedland. Both sides engaged one another for the remainder of the day with no result. Crucially, Bennigsen believed he had enough time to cross the Alle the following day, to destroy the isolated units of Lannes, and to withdraw back across the river without ever encountering the main French army.

The battle

Bennigsen's main body began to occupy the town on the night of 13 June, after Russian forces under General Golitsyn had driven off the French cavalry outposts. The army of Napoleon marched on Friedland, but remained dispersed on its various march routes, and the first stage of the engagement became a purely improvisational battle. Knowing that Napoleon was within supporting distance with at least three corps, Lannes sent aides galloping off with messages for help and waged an expert delaying action to fix Bennigsen in place. With never more than 26,000 men, Lannes forced Bennigsen to commit progressively more troops across the Alle to defeat him.[29] Showing a bold front, and shifting troops where needed to stop Russian advances, the French engaged the Russians first in the Sortlack Wood and in front of Posthenen in the early hours of the 14th. Lannes held Bennigsen in place until the French had massed 80,000 troops on the west bank of the river. Both sides now used their cavalry freely to cover the formation of lines of battle, and a race between the rival squadrons for the possession of Heinrichsdorf ended in favor of the French under Grouchy and Nansouty. Bennigsen was trapped and had to fight. Having thrown all of his pontoon bridges at or near the bottleneck of the village of Friedland, Bennigsen had unwittingly trapped his troops on the west bank.

In the meantime Lannes fought hard to hold Bennigsen. Napoleon feared that the Russians meant to evade him again, but by 6 a.m. Bennigsen had nearly 50,000 men across the river and forming up west of Friedland. His infantry, organized in two lines, extended between the Heinrichsdorf-Friedland road and the upper bends of the river along with the artillery. Beyond the right of the infantry, cavalry and Cossacks extended the line to the wood northeast of Heinrichsdorf. Small bodies of Cossacks penetrated even to Schwonau. The left wing also had some cavalry and, beyond the Alle river, batteries came into action to cover it. A heavy and indecisive fire-fight raged in the Sortlack Wood between the Russian skirmishers and some of Lannes's troops.

The head of Mortier's (French and Polish) corps appeared at Heinrichsdorf and drove the Cossacks out of Schwonau. Lannes held his own, and by noon Napoleon arrived with 40,000 French troops at the scene of the battle.[29] Napoleon gave brief orders: Ney's corps would take the line between Postlienen and the Sortlack Wood, Lannes closing on his left, to form the centre, Mortier at Heinrichsdorf the left wing. I Corps under General Victor and the Imperial Guard were placed in reserve behind Posthenen. Cavalry masses were collected at Heinrichsdorf. The main attack was to be delivered against the Russian left, which Napoleon saw at once to be cramped in the narrow tongue of land between the river and the Posthenen mill-stream. Three cavalry divisions were added to the general reserve.

The course of the previous operations meant that both armies still had large detachments out towards Königsberg. The emperor spent the afternoon in forming up the newly arrived masses, the deployment being covered by an artillery bombardment. At 5 o'clock all was ready, and Ney, preceded by a heavy artillery fire, rapidly carried the Sortlack Wood. The attack was pushed on toward the Alle. Marshal Ney's right-hand division under Marchand drove part of the Russian left into the river at Sortlack, while the division of Bisson advanced on the left. A furious charge by Russian cavalry into the gap between Marchand and Bisson was repulsed by the dragoon division of Latour-Maubourg.

Soon the Russians found themselves huddled together in the bends of the Alle, an easy target for the guns of Ney and of the reserve. Ney's attack indeed came eventually to a standstill; Bennigsen's reserve cavalry charged with great effect and drove him back in disorder. As at Eylau, the approach of night seemed to preclude a decisive success, but in June and on firm ground the old mobility of the French reasserted its value. The infantry division of Dupont advanced rapidly from Posthenen, the cavalry divisions drove back the Russian squadrons into the now congested masses of infantry on the river bank, and finally the artillery general Sénarmont advanced a mass of guns to case-shot range. The terrible effect of the close range artillery saw the Russian defense collapsing within minutes, as canister decimated the ranks. Ney's exhausted infantry succeeded in pursuing the broken regiments of Bennigsen's left into the streets of Friedland. Lannes and Mortier had meanwhile held the Russian centre and right on its ground, and their artillery had inflicted severe losses. When Friedland itself was seen to be on fire, the two marshals launched their infantry attack. Fresh French troops approached the battlefield. Dupont distinguished himself for the second time by fording the mill-stream and assailing the left flank of the Russian centre. This offered stubborn resistance, but the French steadily forced the line backwards, and the battle was soon over.

The Russians suffered heavy losses in the disorganized retreat over the river, with many soldiers drowning. Farther north the still unbroken troops of the right wing withdrew by using the Allenburg road; the French cavalry of the left wing, though ordered to pursue, remained inactive. French casualties numbered approximately 10,000 soldiers while the Russians suffered at least 20,000 casualties.[3]

Results

On 19 June Emperor Alexander sent an envoy to seek an armistice with the French. Napoleon assured the envoy that the Vistula River represented the natural borders between French and Russian influence in Europe. On that basis, the two emperors began peace negotiations at the town of Tilsit after meeting on an iconic raft on the River Niemen. The very first thing Alexander said to Napoleon was probably well-calibrated: "I hate the English as much as you do."[30] Napoleon reportedly replied, "Then we have already made peace." The two emperors spent several days reviewing each other's armies, passing out medals, and frequently talking about non-political subjects.

Although the negotiations at Tilsit featured plenty of pageantry and diplomatic niceties, they were not spared from ruthless politics. Alexander faced pressure from his brother, Duke Constantine, to make peace with Napoleon. Given the victory he had just achieved, the French emperor offered the Russians relatively lenient terms–demanding that Russia join the Continental System, withdraw its forces from Wallachia and Moldavia, and hand over the Ionian Islands to France.[31] By contrast, Napoleon dictated very harsh peace terms for Prussia, despite the ceaseless exhortations of Queen Louise. Wiping out half of Prussian territories from the map, Napoleon created a new kingdom of 1,100 square miles called Westphalia. He then appointed his young brother Jérôme as the new monarch of this kingdom. Prussia's humiliating treatment at Tilsit caused a deep and bitter antagonism which festered as the Napoleonic Era progressed. Moreover, Alexander's pretensions at friendship with Napoleon led the latter to seriously misjudge the true intentions of his Russian counterpart, who would violate numerous provisions of the treaty in the next few years. Despite these problems, Tilsit at last gave Napoleon a respite from war and allowed him to return to France, which he had not seen in over 300 days.[31] His arrival was greeted with huge celebrations in Paris.

The War of the Fourth Coalition was over.

The Peninsular War began in the same year on 19 November 1807.

The War of the Fifth Coalition began in 1809.

The River Niemen was crossed in the French Invasion of Russia in 1812.

In literature and the arts

The battle is mentioned as a pivotal event, though not described, in Leo Tolstoy's War and Peace.[32]: 204, 232

See also

References

- ↑ Everson, Robert E. (2014). Marshal Jean Lannes In The Battles Of Saalfeld, Pultusk, And Friedland, 1806 To 1807: The Application Of Combined Arms In The Opening Battle. Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 9781782899037. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

The Saxons also had a small division with two brigades, two cavalry regiments and two foot batteries in the French reserve Corps at Friedland.

- ↑ Clodfelter 2002.

- 1 2 3 Chandler, 1999: 161

- 1 2 Dowling T. C. Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond. ABC-CLIO. 2014. P. 279: "Napoleon, with 80,000 men and 118 cannon".

- ↑ Chandler, D. The Campaigns of Napoleon. Scribner, 1966, p. 576.

- 1 2 Tucker S. C. A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. 2009. P. 1055: "The Battle of Friedland of June 14, 1807, pits Napoleon with 80,000 men against Bennigsen with only 60,000".

- 1 2 Emsley C. Napoleonic Europe. Routledge. 2014. P. 236

- 1 2 Sandler S. Ground Warfare: An International Encyclopedia, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. 2002. P. 304: "Friedland... A battle in East Prussia between French forces, ultimately numbering 80,000, commanded by Napoleon Bonaparte, and Russian forces, numbering about 46,000 under Levin, Count Bennigsen".

- ↑ Nicholls D. Napoleon: A Biographical Companion. ABC-CLIO. 1999. P. 105: "Some 50,000 Russians under Levin von Bennigsen faced 80,000 of the Grande Armée".

- 1 2 3 Chandler 1995 p. 582.

- ↑ Fisher, Todd & Fremont-Barnes, Gregory. The Napoleonic Wars: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. Osprey Publishing, 2004, p. 90

- ↑ Fisher, 2001: 78

- 1 2 Gregory Fremont-Barnes (editor).The Encyclopedia of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. A Political, Social, and Military History. V. I. ABC CLIO. 2006. P. 388-389.

- ↑ Weigley R. F. The Age of Battles: The Quest for Decisive Warfare from Breitenfeld to Waterloo. Indiana University Press, 2004. P. 407

- ↑ Roberts, Andrews. Napoleon: A Life. Penguin Group, 2014, p. 455

- ↑ Chandler 1995, p. 585. Bourrienne, a French diplomat and formerly Napoleon's secretary, wrote, "The interview at Tilsit is one of the culminating points of modern history, and the waters of the Niemen reflected the image of Napoleon at the height of his glory."

- ↑ McLynn, p. 354

- 1 2 McLynn p. 355

- ↑ McLynn p. 356

- ↑ Chandler 1995 p. 502

- ↑ Chandler 1995 p. 515

- ↑ Todd Fisher and Gregory Fremont-Barnes, The Napoleonic Wars: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. p. 76

- 1 2 Fisher & Fremont-Barnes p. 77

- ↑ Chandler, David. The Campaigns of Napoleon. New York: Macmillan. 1966. P. 536

- ↑ Esdaile Charles J. The Wars of Napoleon. Routledge, 2014. P. 66

- ↑ Fisher & Fremont-Barnes p. 83. 10,700 represents the paper strength of French cavalry at Eylau. It seems very unlikely, however, that all of these squadrons fought at full strength. History may never ascertain the real number of cavalrymen that charged.

- ↑ Fisher & Fremont-Barnes p. 84. Debate continues regarding the casualties at Eylau. Some historians, such as Chandler, put the figures at 25,000 French and 15,000 Russian while others equate the two around either 15,000 or 25,000.

- 1 2 Roberts, A. Napoleon: A Life. Penguin Group, 2014, p. 450.

- 1 2 Roberts, A. Napoleon: A Life. Penguin Group, 2014, p. 452-3.

- ↑ Roberts, A. Napoleon: A Life. Penguin Group, 2014, p. 457.

- 1 2 Roberts, A. Napoleon: A Life. Penguin Group, 2014, p. 458-9.

- ↑ Tolstoy, Leo (1949). War and Peace. Garden City: International Collectors Library.

Notes

- Chandler, David G. The Campaigns of Napoleon. Simon & Schuster, 1995. ISBN 0-02-523660-1

- Elting, John & Esposito, Vincent, A Military History and Atlas of the Napoleonic Wars, Greenhill Books, 1999, ISBN 1-85367-346-3

- Fisher, Todd & Fremont-Barnes, Gregory. The Napoleonic Wars: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. Osprey Publishing. 2004. ISBN 1-84176-831-6

- Hourtoulle, F. G., From Eylau to Friedland, 1807, The Polish Campaign, Histoire & Collections, Paris, 2007, ISBN 978-2-35250-021-6

- McLynn, Frank. Napoleon: A Biography. New York: Arcade Publishing Inc., 1997. ISBN 1-55970-631-7

- Roberts, Andrew Napoleon, A Life. Penguin Group, 2014. ISBN 978-0-670-02532-9

- Summerville, Christopher. Napoleon's Polish Gamble: Eylau & Friedland 1807. Pen & Sword Books, Ltd. 2005, ISBN 1-84415-260-X

- La bataille de Friedland according to General Marbot in his memoirs: Mémoires, Plon, Nourrit et Cie - Paris 1891

External links

- La bataille de Friedland according to General Marbot in his memoirs: Mémoires, Plon, Nourrit et Cie - Paris 1891

- Clodfelter, Micheal (2002). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Reference to Casualty and Other Figures, 1500-2000. McFarland. ISBN 9780786433193. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

Media related to Battle of Friedland at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Battle of Friedland at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by Battle of Heilsberg |

Napoleonic Wars Battle of Friedland |

Succeeded by Siege of Stralsund (1807) |