.jpeg.webp)

Bastimentos was an island, anchorage and harbour near Portobelo on the north-western coast of Panama discovered and named in Spanish "Isle and port of Provisions" by Christopher Columbus in 1502 during his fourth and last voyage.[2] Although the location of the two adjacent Bastimentos Islands (Great and Little) is largely undisputed, the location of the harbour, shown on several 18th century Spanish maps as on the mainland opposite the islands, is suggested by various modern commentators to lie about 7 miles distant, thus its exact location is now uncertain and a matter of conjecture. Harris (2013) states: "by 1513 the record of (Columbus's) discoveries in this small region had become so clouded that it has since generated countless investigations and over the years a voluminous literature has been created in which attempted reconstructions of the voyage often have been conjectural and controversial".[3] Bastimentos was the place where in 1726/7 the British Admiral Francis Hosier with three thousand of his sailors died of tropical disease whilst anchored with his fleet of 20 ships during the disastrous Blockade of Porto Bello. Due to the popularity of Richard Glover's poem and song Admiral Hosier's Ghost (c.1739), which mentions them twice, the Bastimentos became in England synonymous with "foul dishonour" and "shameful doom". The location should not be confused with Bastimentos Island, Bocas del Toro, 270 km to the west, also discovered by Columbus on his 4th Voyage, before reaching Portobelo.

Discovery by Columbus

Bastimentos was one of the easternmost discoveries of Columbus on the mainland of South America, which ended at a place he named Retrete’ (thought to be today's Puerto Escribanos[4]), after which he set sail to the north into the Caribbean. He had failed to discover the Pacific Ocean, just 43 miles to the south of Bastimentos across the isthmus of Panama.

Columbus had sailed from Cádiz on his fourth voyage on May 9, 1502 and made landfall at Martinique on June 15. He proceeded to sail in an anti-clockwise direction around the islands, and then crossing the Caribbean in a southerly direction he met the mainland and continued exploring the coast to the east. Having given up his quest at Retrete on April 16, 1503 he set sail for home via Hispaniola but due to a storm had to beach his fleet on the coast of Jamaica, where by June 1503 he and his crews were little better than castaways. He had hoped, as he said to his sovereign patrons, that "my hard and troublesome voyage may yet turn out to be my noblest", but it turned out to have been "the most disappointing of all and the most unlucky".

Account by Ferdinand Columbus

Although a complete list of crew members and payroll details survive from his 4th Voyage, Columbus's own journal of this particular stage of his Voyage has not survived.[5] However one of his letters did survive[6] and more importantly his son Ferdinand Columbus, who as a young boy had accompanied his father, later wrote an account of the Voyage.[7] Ferdinand relates as follows regarding the discovery of Bastimentos, the expedition having just discovered and named the port of Porto Bello, 8 miles to the west of Bastimentos:

- "Wednesday, November 9th (1502), we left Portobelo and sailed eight leagues eastward, but the next day were forced back four by a contrary wind, and so put in among some islets near the mainland where Nombre de Dios now is.[8] Because all the land about and the islets were full of maize fields, the Admiral named it Puerto de Bastimentos (i.e. "Port of Provisions"). In this harbor one of our boats haled a canoe of Indians, they, thinking our people meant them harm and seeing the boat only a stone's throw away, cast themselves into the water and tried to escape by swimming. And no matter how hard our men rowed they could not catch them over the half-league that the chase continued. When they caught up with one, he would dive like a water-fowl and come up a bowshot or two distant. It was really funny to see the boat giving chase and the rowers wearing themselves out in vain, for they finally had to return empty-handed. We remained there until November 23d, repairing the ships and mending our casks, then we sailed eastward to a place called Guiga".

On 23 November 1502 the fleet left Bastimentos on its eastward progress, shortly passing the natural harbour which in 1508 was named Nombre de Dios ("name of God") by the Spanish conquistador and explorer Diego de Nicuesa (d.1511), for the same reason Columbus named Gracias a Dios.[9]

Bastimentos today

The island shown on Spanish maps made in about 1700 as Isla Grande de Bastimentos (Big Island of Bastimentos) is today known as “Isla Grande”,[1] and is joined by a short reef to the small island on the north called in the old maps Isla de Bastimentos Chica (Little Island of Bastimentos). The natural inlet or harbour 1 km to the south on the mainland is marked as Puerto de Bastimentos (Port of Bastimentos), and an inverted anchor is drawn in its midst indicating the position of the anchorage, with depths marked as 6 and 7 fathoms. However Morison equates Puerto de Bastimentos / El Puerto de Bastimentos de Colon with the port of Nombre de Dios,[10] 7 miles to the east.[8]

Another larger island 1.3 km to the immediate west of Isla Grande de Bastimentos is marked on the old map as Isla Grande de Monos (also joined by a short reef on the north-east by a smaller island, Isla de Monos Chica) and is today known as Isla Linton. An anchorage to the south of it is now used as a yacht haven, known as Linton Bay.[11]

Strategic location of Bastimentos

Bastimentos was situated in a strategically important position due to its proximity as an anchorage within range of the harbor of the Spanish port of Nombre de Dios, 7 miles to the east, which became the principal Atlantic port used by the Spanish treasure fleet for the export of Peruvian silver, transported up the South American coast to the Pacific port of Panama and then transported north across the isthmus by mule train. After the capture and sack of Nombre de Dios the Spanish moved their Atlantic-side operations 13 miles to the west, to the more secure port of Porto Bello, 8 miles to the west of Bastimentos.

Bastimentos in history

Used as a base by Bartholomew Sharp, 1680

In January 1680 during the second sacking of Porto Bello (the first having been done by the British pirate Henry Morgan in 1671), a party led by the English buccaneer and privateer Bartholomew Sharp captured the town of Porto Bello within that harbour, which he held and plundered for two days, the population having taken refuge in the fortress of "Gloria". Some of the booty was brought out in canoes whilst the remainder was taken overland down to Puerto Bastimentos and from there they carried their prisoners and plunder to "a key lying about half a mile from the mainland".[12][13] Three days later a force of about 700 Spanish troops from Panama and Porto Bello converged on their position and fired small arms at them "shooting clear over this key". Sharp then moved to an adjoining island ("another key hard by") out of range of the troops, where he was met by his ships. Sharp's group then captured a barque longo headed to Portobelo with its cargo of salt and corn, having been loaded at Cartagena in the east. Three days later they captured another, a "good big ship" of 90 tons with 8 guns, also from Cartagena and headed to Porto Bello, loaded with a cargo of African slaves, timber, salt, corn and silk with "packets of great concern from the King of Spain".[14]

Used as a base by Admiral Hosier, 1726

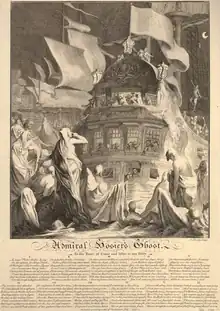

The "Bastimentos" was later the place where the British Admiral Francis Hosier anchored his fleet of 20 ships during the disastrous Blockade of Porto Bello in 1726/7, having been ordered by his government to refrain from attacking the port, which was largely undefended, but to wait for months unoccupied. The objective had been to prevent the Spanish treasure fleet sailing for home. The episode is described as follows in Percy's Reliques of 1765: "He (Hosier) accordingly arrived at the Bastimentos near Porto Bello, but being employed rather to overawe than to attack the Spaniards, with whom it was probably not our interest to go to war, he continued long inactive on that station, to his own great regret". Several of his letters to the government during this period are dated at "Bastimentos". About three thousand of his sailors died here of tropical disease and the bottoms of his ships were eaten by shipworm. The event was felt by the British people as a national humiliation, for which they largely blamed the government. Hosier's humiliation was later vindicated in November 1739 with Admiral Vernon's Capture of Porto Bello (with only 6 ships), an event that raised the British public's joy to fever pitch and inspired the writing of Rule, Britannia! Britannia Rule the Waves!. Following Vernon's victory, Richard Glover composed the poem and song Admiral Hosier's Ghost, which relates the events and mentions the Bastimentos twice, once as a place of "foul dishonour" and again as a "shameful doom". A contemporary illustration shows the ghosts of Hosier and his 3,000 men rising from the water at Bastimentos to plead with Vernon, then anchored at rest after his victory, to remember their sad fate.

Verse VI

'I by twenty sail attended,

'Did this Spanish town affright,

'Nothing then its wealth defended

'But my orders not to fight;

'Oh that with my wrath complying,

'I had cast them in the main,

'Then no more unactive lying,

'I had low'red the pride of Spain. (verse 6)

Verse VII

'For resistance I could fear none,

'But with twenty ships had done,

'What thou brave and happy Vernon,

'Did'st achieve with six alone.

'Then the Bastimento's never

'Had our foul dishonour seen,

'Nor the sea the sad receiver

'Of these gallant men had been. (verse 7)

Verse X

'Hence with all my train attending

'From their oozy tombs below,

'Through the hoary foam ascending

'Here I feed my constant woe;

'Here the Bastimento's viewing,

'We recal our shameful doom,

'And our plaintive cries renewing,

'Wander through the mighnight gloom.

Further reading

- Samuel Eliot Morison, Admiral of the Ocean Sea, 2 Vols, Boston, 1942, Vol.2, p. 354-5

- Morison, European Discovery

- Carl Ortwin Sauer, The Early Spanish Main, p. 126

- John Logan Allen (ed.), North American Exploration, p. 185

- Privateering and Piracy in the Colonial Period: Illustrative Documents

- Bartholomew Sharp and others, 44: The Buccaneers at Portobello, 1680, published in Privateering and Piracy in the Colonial Period: Illustrative Documents refers to “the next keys to the Bastamentes”. Re buccaneers associated with John Coxon

- James E. Wadsworth, Global Piracy: A Documentary History of Seaborne Banditry Re buccaneers associated with Bartholomew Sharpe and John Coxon

- Felipe Fernández-Armesto, Columbus on Himself, p. 223

References

- 1 2 Lewis D. Harris

- ↑ Columbus' Easternmost Discoveries in Panama: A Geographical Appraisal Lewis D. Harris pp. 25-36, published in Terrae Incognitae , The Journal of the Society for the History of Discoveries Volume 16, 1984 - Issue 1

- ↑ Lewis D. Harris, Columbus' Easternmost Discoveries in Panama: A Geographical Appraisal, published in Terrae Incognitae, The Journal of the Society for the History of Discoveries Volume 16, 1984, Issue 1, pp.25-36

- ↑ Retrete equated with Puerto Escribanos (near Santa Isabel) by Morison, Admiral of the Ocean Sea, vol.2, p.614

- ↑ "Christopher Columbus - Principal evidence of travels".

- ↑ "Home". britannica.com.

- ↑ The Life Of The Admiral Christopher Columbus By His Son Ferdinand, translated and annotated by Benjamin Keen , New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA, 1934, p.243 (Chapter 93)

- 1 2 There are no islands near the harbour of Nombre de Dios, see google maps

- ↑ Morison, Vol.2, p.354

- ↑ Morison, European Discovery, p.24 equates Puerto de Bastimentos with Nombre de Dios, quoted in Columbus on Himself, p.223 (note), By Felipe Fernández-Armesto

- ↑ See YouTube video of Linton Bay with yachts at anchor

- ↑ James E. Wadsworth, Global Piracy: A Documentary History of Seaborne Banditry, London, 2019

- ↑ Note, there are no islands near Nombre de Dios (see google maps ) which rules out Bartholomew Sharp's Puerto Bastimentos being Nombre de Dios, as Morison suggests

- ↑ Global Piracy: A Documentary History of Seaborne Banditry By James E. Wadsworth