Chris Dudley (#22), playing for the New Jersey Nets, squares off with Michael Jordan (#23), of the Chicago Bulls on March 28, 1991. Other players including Chicago's Bill Cartwright (#24) are present on the court. | |

| Highest governing body | FIBA |

|---|---|

| First played | December 21, 1891. Springfield, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | Limited |

| Team members | 5 per side |

| Mixed-sex | Yes, separate competitions |

| Type | Indoor/Outdoor |

| Equipment | Basketball |

| Venue | Indoor court (mainly) or outdoor court (Streetball) |

| Glossary | Glossary of basketball |

| Presence | |

| Country or region | Worldwide |

| Olympic | Yes, demonstrated in the 1904 and 1924 Summer Olympics Part of the Summer Olympic program since 1936 |

| Paralympic | Yes |

Basketball is a team sport in which two teams, most commonly of five players each, opposing one another on a rectangular court, compete with the primary objective of shooting a basketball (approximately 9.4 inches (24 cm) in diameter) through the defender's hoop (a basket 18 inches (46 cm) in diameter mounted 10 feet (3.048 m) high to a backboard at each end of the court), while preventing the opposing team from shooting through their own hoop. A field goal is worth two points, unless made from behind the three-point line, when it is worth three. After a foul, timed play stops and the player fouled or designated to shoot a technical foul is given one, two or three one-point free throws. The team with the most points at the end of the game wins, but if regulation play expires with the score tied, an additional period of play (overtime) is mandated.

Players advance the ball by bouncing it while walking or running (dribbling) or by passing it to a teammate, both of which require considerable skill. On offense, players may use a variety of shots – the layup, the jump shot, or a dunk; on defense, they may steal the ball from a dribbler, intercept passes, or block shots; either offense or defense may collect a rebound, that is, a missed shot that bounces from rim or backboard. It is a violation to lift or drag one's pivot foot without dribbling the ball, to carry it, or to hold the ball with both hands then resume dribbling.

The five players on each side fall into five playing positions. The tallest player is usually the center, the second-tallest and strongest is the power forward, a slightly shorter but more agile player is the small forward, and the shortest players or the best ball handlers are the shooting guard and the point guard, who implement the coach's game plan by managing the execution of offensive and defensive plays (player positioning). Informally, players may play three-on-three, two-on-two, and one-on-one.

Invented in 1891 by Canadian-American gym teacher James Naismith in Springfield, Massachusetts, in the United States, basketball has evolved to become one of the world's most popular and widely viewed sports.[1][2] The National Basketball Association (NBA) is the most significant professional basketball league in the world in terms of popularity, salaries, talent, and level of competition[3][4] (drawing most of its talent from U.S. college basketball). Outside North America, the top clubs from national leagues qualify to continental championships such as the EuroLeague and the Basketball Champions League Americas. The FIBA Basketball World Cup and Men's Olympic Basketball Tournament are the major international events of the sport and attract top national teams from around the world. Each continent hosts regional competitions for national teams, like EuroBasket and FIBA AmeriCup.

The FIBA Women's Basketball World Cup and Women's Olympic Basketball Tournament feature top national teams from continental championships. The main North American league is the WNBA (NCAA Women's Division I Basketball Championship is also popular), whereas the strongest European clubs participate in the EuroLeague Women.

History

Creation

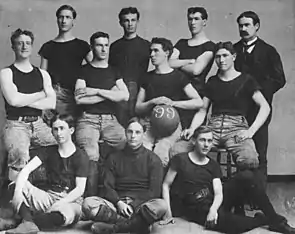

In December 1891, James Naismith, a Canadian-American professor of physical education and instructor at the International Young Men's Christian Association Training School (now Springfield College) in Springfield, Massachusetts,[5] was trying to keep his gym class active on a rainy day.[6] He sought a vigorous indoor game to keep his students occupied and at proper levels of fitness during the long New England winters. After rejecting other ideas as either too rough or poorly suited to walled-in gymnasiums, he invented a new game in which players would pass a ball to teammates and try to score points by tossing the ball into a basket mounted on a wall. Naismith wrote the basic rules and nailed a peach basket onto an elevated track. Naismith initially set up the peach basket with its bottom intact, which meant that the ball had to be retrieved manually after each "basket" or point scored. This quickly proved tedious, so Naismith removed the bottom of the basket to allow the balls to be poked out with a long dowel after each scored basket.

Basketball was originally played with a soccer ball. These round balls from "association football" were made, at the time, with a set of laces to close off the hole needed for inserting the inflatable bladder after the other sewn-together segments of the ball's cover had been flipped outside-in.[7][8] These laces could cause bounce passes and dribbling to be unpredictable.[9] Eventually a lace-free ball construction method was invented, and this change to the game was endorsed by Naismith (whereas in American football, the lace construction proved to be advantageous for gripping and remains to this day). The first balls made specifically for basketball were brown, and it was only in the late 1950s that Tony Hinkle, searching for a ball that would be more visible to players and spectators alike, introduced the orange ball that is now in common use. Dribbling was not part of the original game except for the "bounce pass" to teammates. Passing the ball was the primary means of ball movement. Dribbling was eventually introduced but limited by the asymmetric shape of early balls. Dribbling was common by 1896, with a rule against the double dribble by 1898.[10]

The peach baskets were used until 1906 when they were finally replaced by metal hoops with backboards. A further change was soon made, so the ball merely passed through. Whenever a person got the ball in the basket, his team would gain a point. Whichever team got the most points won the game.[11] The baskets were originally nailed to the mezzanine balcony of the playing court, but this proved impractical when spectators in the balcony began to interfere with shots. The backboard was introduced to prevent this interference; it had the additional effect of allowing rebound shots.[12] Naismith's handwritten diaries, discovered by his granddaughter in early 2006, indicate that he was nervous about the new game he had invented, which incorporated rules from a children's game called duck on a rock, as many had failed before it.[13]

Frank Mahan, one of the players from the original first game, approached Naismith after the Christmas break, in early 1892, asking him what he intended to call his new game. Naismith replied that he had not thought of it because he had been focused on just getting the game started. Mahan suggested that it be called "Naismith ball", at which he laughed, saying that a name like that would kill any game. Mahan then said, "Why not call it basketball?" Naismith replied, "We have a basket and a ball, and it seems to me that would be a good name for it."[14][15] The first official game was played in the YMCA gymnasium in Albany, New York, on January 20, 1892, with nine players. The game ended at 1–0; the shot was made from 25 feet (7.6 m), on a court just half the size of a present-day Streetball or National Basketball Association (NBA) court.

At the time, soccer was being played with 10 to a team (which was increased to 11). When winter weather got too icy to play soccer, teams were taken indoors, and it was convenient to have them split in half and play basketball with five on each side. By 1897–98, teams of five became standard.

College basketball

Basketball's early adherents were dispatched to YMCAs throughout the United States, and it quickly spread through the United States and Canada. By 1895, it was well established at several women's high schools. While YMCA was responsible for initially developing and spreading the game, within a decade it discouraged the new sport, as rough play and rowdy crowds began to detract from YMCA's primary mission. However, other amateur sports clubs, colleges, and professional clubs quickly filled the void. In the years before World War I, the Amateur Athletic Union and the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States (forerunner of the NCAA) vied for control over the rules for the game. The first pro league, the National Basketball League, was formed in 1898 to protect players from exploitation and to promote a less rough game. This league only lasted five years.

James Naismith was instrumental in establishing college basketball. His colleague C. O. Beamis fielded the first college basketball team just a year after the Springfield YMCA game at the suburban Pittsburgh Geneva College.[16] Naismith himself later coached at the University of Kansas for six years, before handing the reins to renowned coach Forrest "Phog" Allen. Naismith's disciple Amos Alonzo Stagg brought basketball to the University of Chicago, while Adolph Rupp, a student of Naismith's at Kansas, enjoyed great success as coach at the University of Kentucky. On February 9, 1895, the first intercollegiate 5-on-5 game was played at Hamline University between Hamline and the School of Agriculture, which was affiliated with the University of Minnesota.[17][18][19] The School of Agriculture won in a 9–3 game.

In 1901, colleges, including the University of Chicago, Columbia University, Cornell University, Dartmouth College, the University of Minnesota, the U.S. Naval Academy, the University of Colorado and Yale University began sponsoring men's games. In 1905, frequent injuries on the football field prompted President Theodore Roosevelt to suggest that colleges form a governing body, resulting in the creation of the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States (IAAUS). In 1910, that body changed its name to the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA). The first Canadian interuniversity basketball game was played at YMCA in Kingston, Ontario on February 6, 1904, when McGill University – Naismith's alma mater – visited Queen's University. McGill won 9–7 in overtime; the score was 7–7 at the end of regulation play, and a ten-minute overtime period settled the outcome. A good turnout of spectators watched the game.[20]

The first men's national championship tournament, the National Association of Intercollegiate Basketball tournament, which still exists as the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) tournament, was organized in 1937. The first national championship for NCAA teams, the National Invitation Tournament (NIT) in New York, was organized in 1938; the NCAA national tournament began one year later. College basketball was rocked by gambling scandals from 1948 to 1951, when dozens of players from top teams were implicated in match fixing and point shaving. Partially spurred by an association with cheating, the NIT lost support to the NCAA tournament.

High school basketball

Before widespread school district consolidation, most American high schools were far smaller than their present-day counterparts. During the first decades of the 20th century, basketball quickly became the ideal interscholastic sport due to its modest equipment and personnel requirements. In the days before widespread television coverage of professional and college sports, the popularity of high school basketball was unrivaled in many parts of America. Perhaps the most legendary of high school teams was Indiana's Franklin Wonder Five, which took the nation by storm during the 1920s, dominating Indiana basketball and earning national recognition.

Today virtually every high school in the United States fields a basketball team in varsity competition.[21] Basketball's popularity remains high, both in rural areas where they carry the identification of the entire community, as well as at some larger schools known for their basketball teams where many players go on to participate at higher levels of competition after graduation. In the 2016–17 season, 980,673 boys and girls represented their schools in interscholastic basketball competition, according to the National Federation of State High School Associations.[22] The states of Illinois, Indiana and Kentucky are particularly well known for their residents' devotion to high school basketball, commonly called Hoosier Hysteria in Indiana; the critically acclaimed film Hoosiers shows high school basketball's depth of meaning to these communities.

_(14779954132).jpg.webp)

There is currently no tournament to determine a national high school champion. The most serious effort was the National Interscholastic Basketball Tournament at the University of Chicago from 1917 to 1930. The event was organized by Amos Alonzo Stagg and sent invitations to state champion teams. The tournament started out as a mostly Midwest affair but grew. In 1929 it had 29 state champions. Faced with opposition from the National Federation of State High School Associations and North Central Association of Colleges and Schools that bore a threat of the schools losing their accreditation the last tournament was in 1930. The organizations said they were concerned that the tournament was being used to recruit professional players from the prep ranks.[23] The tournament did not invite minority schools or private/parochial schools.

The National Catholic Interscholastic Basketball Tournament ran from 1924 to 1941 at Loyola University.[24] The National Catholic Invitational Basketball Tournament from 1954 to 1978 played at a series of venues, including Catholic University, Georgetown and George Mason.[25] The National Interscholastic Basketball Tournament for Black High Schools was held from 1929 to 1942 at Hampton Institute.[26] The National Invitational Interscholastic Basketball Tournament was held from 1941 to 1967 starting out at Tuskegee Institute. Following a pause during World War II it resumed at Tennessee State College in Nashville. The basis for the champion dwindled after 1954 when Brown v. Board of Education began an integration of schools. The last tournaments were held at Alabama State College from 1964 to 1967.[27]

Professional basketball

Teams abounded throughout the 1920s. There were hundreds of men's professional basketball teams in towns and cities all over the United States, and little organization of the professional game. Players jumped from team to team and teams played in armories and smoky dance halls. Leagues came and went. Barnstorming squads such as the Original Celtics and two all-African American teams, the New York Renaissance Five ("Rens") and the (still existing) Harlem Globetrotters played up to two hundred games a year on their national tours.

In 1946, the Basketball Association of America (BAA) was formed. The first game was played in Toronto, Ontario, Canada between the Toronto Huskies and New York Knickerbockers on November 1, 1946. Three seasons later, in 1949, the BAA merged with the National Basketball League (NBL) to form the National Basketball Association (NBA). By the 1950s, basketball had become a major college sport, thus paving the way for a growth of interest in professional basketball. In 1959, a basketball hall of fame was founded in Springfield, Massachusetts, site of the first game. Its rosters include the names of great players, coaches, referees and people who have contributed significantly to the development of the game. The hall of fame has people who have accomplished many goals in their career in basketball. An upstart organization, the American Basketball Association, emerged in 1967 and briefly threatened the NBA's dominance until the ABA-NBA merger in 1976. Today the NBA is the top professional basketball league in the world in terms of popularity, salaries, talent, and level of competition.

The NBA has featured many famous players, including George Mikan, the first dominating "big man"; ball-handling wizard Bob Cousy and defensive genius Bill Russell of the Boston Celtics; charismatic center Wilt Chamberlain, who originally played for the barnstorming Harlem Globetrotters; all-around stars Oscar Robertson and Jerry West; more recent big men Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Shaquille O'Neal, Hakeem Olajuwon and Karl Malone; playmakers John Stockton, Isiah Thomas and Steve Nash; crowd-pleasing forwards Julius Erving and Charles Barkley; European stars Dirk Nowitzki, Pau Gasol and Tony Parker; Latin American stars Manu Ginobili, more recent superstars, Allen Iverson, Kobe Bryant, Tim Duncan, LeBron James, Stephen Curry, Giannis Antetokounmpo, etc.; and the three players who many credit with ushering the professional game to its highest level of popularity during the 1980s and 1990s: Larry Bird, Earvin "Magic" Johnson, and Michael Jordan.

In 2001, the NBA formed a developmental league, the National Basketball Development League (later known as the NBA D-League and then the NBA G League after a branding deal with Gatorade). As of the 2021–22 season, the G League has 30 teams.

International basketball

FIBA (International Basketball Federation) was formed in 1932 by eight founding nations: Argentina, Czechoslovakia, Greece, Italy, Latvia, Portugal, Romania and Switzerland. At this time, the organization only oversaw amateur players. Its acronym, derived from the French Fédération Internationale de Basket-ball Amateur, was thus "FIBA". Men's basketball was first included at the Berlin 1936 Summer Olympics, although a demonstration tournament was held in 1904. The United States defeated Canada in the first final, played outdoors. This competition has usually been dominated by the United States, whose team has won all but three titles. The first of these came in a controversial final game in Munich in 1972 against the Soviet Union, in which the ending of the game was replayed three times until the Soviet Union finally came out on top.[28] In 1950 the first FIBA World Championship for men, now known as the FIBA Basketball World Cup, was held in Argentina. Three years later, the first FIBA World Championship for women, now known as the FIBA Women's Basketball World Cup, was held in Chile. Women's basketball was added to the Olympics in 1976, which were held in Montreal, Quebec, Canada with teams such as the Soviet Union, Brazil and Australia rivaling the American squads.

In 1989, FIBA allowed professional NBA players to participate in the Olympics for the first time. Prior to the 1992 Summer Olympics, only European and South American teams were allowed to field professionals in the Olympics. The United States' dominance continued with the introduction of the original Dream Team. In the 2004 Athens Olympics, the United States suffered its first Olympic loss while using professional players, falling to Puerto Rico (in a 19-point loss) and Lithuania in group games, and being eliminated in the semifinals by Argentina. It eventually won the bronze medal defeating Lithuania, finishing behind Argentina and Italy. The Redeem Team, won gold at the 2008 Olympics, and the B-Team, won gold at the 2010 FIBA World Championship in Turkey despite featuring no players from the 2008 squad. The United States continued its dominance as they won gold at the 2012 Olympics, 2014 FIBA World Cup and the 2016 Olympics.

Worldwide, basketball tournaments are held for boys and girls of all age levels. The global popularity of the sport is reflected in the nationalities represented in the NBA. Players from all six inhabited continents currently play in the NBA. Top international players began coming into the NBA in the mid-1990s, including Croatians Dražen Petrović and Toni Kukoč, Serbian Vlade Divac, Lithuanians Arvydas Sabonis and Šarūnas Marčiulionis, Dutchman Rik Smits and German Detlef Schrempf.

In the Philippines, the Philippine Basketball Association's first game was played on April 9, 1975, at the Araneta Coliseum in Cubao, Quezon City, Philippines. It was founded as a "rebellion" of several teams from the now-defunct Manila Industrial and Commercial Athletic Association, which was tightly controlled by the Basketball Association of the Philippines (now defunct), the then-FIBA recognized national association. Nine teams from the MICAA participated in the league's first season that opened on April 9, 1975. The NBL is Australia's pre-eminent men's professional basketball league. The league commenced in 1979, playing a winter season (April–September) and did so until the completion of the 20th season in 1998. The 1998–99 season, which commenced only months later, was the first season after the shift to the current summer season format (October–April). This shift was an attempt to avoid competing directly against Australia's various football codes. It features 8 teams from around Australia and one in New Zealand. A few players including Luc Longley, Andrew Gaze, Shane Heal, Chris Anstey and Andrew Bogut made it big internationally, becoming poster figures for the sport in Australia. The Women's National Basketball League began in 1981.

Women's basketball

Women's basketball began in 1892 at Smith College when Senda Berenson, a physical education teacher, modified Naismith's rules for women. Shortly after she was hired at Smith, she went to Naismith to learn more about the game.[29] Fascinated by the new sport and the values it could teach, she organized the first women's collegiate basketball game on March 21, 1893, when her Smith freshmen and sophomores played against one another.[30] However, the first women's interinstitutional game was played in 1892 between the University of California and Miss Head's School.[31] Berenson's rules were first published in 1899, and two years later she became the editor of A. G. Spalding's first Women's Basketball Guide.[30] Berenson's freshmen played the sophomore class in the first women's intercollegiate basketball game at Smith College, March 21, 1893.[32] The same year, Mount Holyoke and Sophie Newcomb College (coached by Clara Gregory Baer) women began playing basketball. By 1895, the game had spread to colleges across the country, including Wellesley, Vassar, and Bryn Mawr. The first intercollegiate women's game was on April 4, 1896. Stanford women played Berkeley, 9-on-9, ending in a 2–1 Stanford victory.

Women's basketball development was more structured than that for men in the early years. In 1905, the executive committee on Basket Ball Rules (National Women's Basketball Committee) was created by the American Physical Education Association.[33] These rules called for six to nine players per team and 11 officials. The International Women's Sports Federation (1924) included a women's basketball competition. 37 women's high school varsity basketball or state tournaments were held by 1925. And in 1926, the Amateur Athletic Union backed the first national women's basketball championship, complete with men's rules.[33] The Edmonton Grads, a touring Canadian women's team based in Edmonton, Alberta, operated between 1915 and 1940. The Grads toured all over North America, and were exceptionally successful. They posted a record of 522 wins and only 20 losses over that span, as they met any team that wanted to challenge them, funding their tours from gate receipts.[34] The Grads also shone on several exhibition trips to Europe, and won four consecutive exhibition Olympics tournaments, in 1924, 1928, 1932, and 1936; however, women's basketball was not an official Olympic sport until 1976. The Grads' players were unpaid, and had to remain single. The Grads' style focused on team play, without overly emphasizing skills of individual players. The first women's AAU All-America team was chosen in 1929.[33] Women's industrial leagues sprang up throughout the United States, producing famous athletes, including Babe Didrikson of the Golden Cyclones, and the All American Red Heads Team, which competed against men's teams, using men's rules. By 1938, the women's national championship changed from a three-court game to two-court game with six players per team.[33]

The NBA-backed Women's National Basketball Association (WNBA) began in 1997. Though it had shaky attendance figures, several marquee players (Lisa Leslie, Diana Taurasi, and Candace Parker among others) have helped the league's popularity and level of competition. Other professional women's basketball leagues in the United States, such as the American Basketball League (1996–98), have folded in part because of the popularity of the WNBA. The WNBA has been looked at by many as a niche league. However, the league has recently taken steps forward. In June 2007, the WNBA signed a contract extension with ESPN. The new television deal ran from 2009 to 2016. Along with this deal, came the first-ever rights fees to be paid to a women's professional sports league. Over the eight years of the contract, "millions and millions of dollars" were "dispersed to the league's teams." In a March 12, 2009, article, NBA commissioner David Stern said that in the bad economy, "the NBA is far less profitable than the WNBA. We're losing a lot of money among a large number of teams. We're budgeting the WNBA to break even this year."[35]

Rules and regulations

Measurements and time limits discussed in this section often vary among tournaments and organizations; international and NBA rules are used in this section.

The object of the game is to outscore one's opponents by throwing the ball through the opponents' basket from above while preventing the opponents from doing so on their own. An attempt to score in this way is called a shot. A successful shot is worth two points, or three points if it is taken from beyond the three-point arc 6.75 metres (22 ft 2 in) from the basket in international games[36] and 23 feet 9 inches (7.24 m) in NBA games.[37] A one-point shot can be earned when shooting from the foul line after a foul is made. After a team has scored from a field goal or free throw, play is resumed with a throw-in awarded to the non-scoring team taken from a point beyond the endline of the court where the points were scored.[38]

Playing regulations

Games are played in four quarters of 10 (FIBA)[39] or 12 minutes (NBA).[40] College men's games use two 20-minute halves,[41] college women's games use 10-minute quarters,[42] and most United States high school varsity games use 8-minute quarters; however, this varies from state to state.[43][44] 15 minutes are allowed for a half-time break under FIBA, NBA, and NCAA rules[41][45][46] and 10 minutes in United States high schools.[43] Overtime periods are five minutes in length[41][47][48] except for high school, which is four minutes in length.[43] Teams exchange baskets for the second half. The time allowed is actual playing time; the clock is stopped while the play is not active. Therefore, games generally take much longer to complete than the allotted game time, typically about two hours.

Five players from each team may be on the court at one time.[49][50][51][52] Substitutions are unlimited but can only be done when play is stopped. Teams also have a coach, who oversees the development and strategies of the team, and other team personnel such as assistant coaches, managers, statisticians, doctors and trainers.

For both men's and women's teams, a standard uniform consists of a pair of shorts and a jersey with a clearly visible number, unique within the team, printed on both the front and back. Players wear high-top sneakers that provide extra ankle support. Typically, team names, players' names and, outside of North America, sponsors are printed on the uniforms.

A limited number of time-outs, clock stoppages requested by a coach (or sometimes mandated in the NBA) for a short meeting with the players, are allowed. They generally last no longer than one minute (100 seconds in the NBA) unless, for televised games, a commercial break is needed.

The game is controlled by the officials consisting of the referee (referred to as crew chief in the NBA), one or two umpires (referred to as referees in the NBA) and the table officials. For college, the NBA, and many high schools, there are a total of three referees on the court. The table officials are responsible for keeping track of each team's scoring, timekeeping, individual and team fouls, player substitutions, team possession arrow, and the shot clock.

Equipment

The only essential equipment in a basketball game is the ball and the court: a flat, rectangular surface with baskets at opposite ends. Competitive levels require the use of more equipment such as clocks, score sheets, scoreboards, alternating possession arrows, and whistle-operated stop-clock systems.

A regulation basketball court in international games is 28 meters (92 feet) long and 15 meters (49 feet) wide. In the NBA and NCAA the court is 94 by 50 feet (29 by 15 meters).[37] Most courts have wood flooring, usually constructed from maple planks running in the same direction as the longer court dimension.[53][54] The name and logo of the home team is usually painted on or around the center circle.

The basket is a steel rim 18 inches (46 cm) diameter with an attached net affixed to a backboard that measures 6 by 3.5 feet (1.8 by 1.1 meters) and one basket is at each end of the court. The white outlined box on the backboard is 18 inches (46 cm) high and 2 feet (61 cm) wide. At almost all levels of competition, the top of the rim is exactly 10 feet (3.05 meters) above the court and 4 feet (1.22 meters) inside the baseline. While variation is possible in the dimensions of the court and backboard, it is considered important for the basket to be of the correct height – a rim that is off by just a few inches can have an adverse effect on shooting. The net must "check the ball momentarily as it passes through the basket" to aid the visual confirmation that the ball went through.[55] The act of checking the ball has the further advantage of slowing down the ball so the rebound does not go as far.[56]

The size of the basketball is also regulated. For men, the official ball is 29.5 inches (75 cm) in circumference (size 7, or a "295 ball") and weighs 22 oz (620 g). If women are playing, the official basketball size is 28.5 inches (72 cm) in circumference (size 6, or a "285 ball") with a weight of 20 oz (570 g). In 3x3, a formalized version of the halfcourt 3-on-3 game, a dedicated ball with the circumference of a size 6 ball but the weight of a size 7 ball is used in all competitions (men's, women's, and mixed teams).[57]

Violations

The ball may be advanced toward the basket by being shot, passed between players, thrown, tapped, rolled or dribbled (bouncing the ball while running).

The ball must stay within the court; the last team to touch the ball before it travels out of bounds forfeits possession. The ball is out of bounds if it touches a boundary line, or touches any player or object that is out of bounds.

There are limits placed on the steps a player may take without dribbling, which commonly results in an infraction known as traveling. Nor may a player stop their dribble and then resume dribbling. A dribble that touches both hands is considered stopping the dribble, giving this infraction the name double dribble. Within a dribble, the player cannot carry the ball by placing their hand on the bottom of the ball; doing so is known as carrying the ball. A team, once having established ball control in the front half of their court, may not return the ball to the backcourt and be the first to touch it. A violation of these rules results in loss of possession.

The ball may not be kicked, nor be struck with the fist. For the offense, a violation of these rules results in loss of possession; for the defense, most leagues reset the shot clock and the offensive team is given possession of the ball out of bounds.

There are limits imposed on the time taken before progressing the ball past halfway (8 seconds in FIBA and the NBA; 10 seconds in NCAA and high school for both sexes), before attempting a shot (24 seconds in FIBA, the NBA, and U Sports (Canadian universities) play for both sexes, and 30 seconds in NCAA play for both sexes), holding the ball while closely guarded (5 seconds), and remaining in the restricted area known as the free-throw lane, (or the "key") (3 seconds). These rules are designed to promote more offense.

There are also limits on how players may block an opponent's field goal attempt or help a teammate's field goal attempt. Goaltending is a defender's touching of a ball that is on a downward flight toward the basket, while the related violation of basket interference is the touching of a ball that is on the rim or above the basket, or by a player reaching through the basket from below. Goaltending and basket interference committed by a defender result in awarding the basket to the offense, while basket interference committed by an offensive player results in cancelling the basket if one is scored. The defense gains possession in all cases of goaltending or basket interference.

Fouls

An attempt to unfairly disadvantage an opponent through certain types of physical contact is illegal and is called a personal foul. These are most commonly committed by defensive players; however, they can be committed by offensive players as well. Players who are fouled either receive the ball to pass inbounds again, or receive one or more free throws if they are fouled in the act of shooting, depending on whether the shot was successful. One point is awarded for making a free throw, which is attempted from a line 15 feet (4.6 m) from the basket.

The referee is responsible for judging whether contact is illegal, sometimes resulting in controversy. The calling of fouls can vary between games, leagues and referees.

There is a second category of fouls called technical fouls, which may be charged for various rules violations including failure to properly record a player in the scorebook, or for unsportsmanlike conduct. These infractions result in one or two free throws, which may be taken by any of the five players on the court at the time. Repeated incidents can result in disqualification. A blatant foul involving physical contact that is either excessive or unnecessary is called an intentional foul (flagrant foul in the NBA). In FIBA and NCAA women's basketball, a foul resulting in ejection is called a disqualifying foul, while in leagues other than the NBA, such a foul is referred to as flagrant.

If a team exceeds a certain limit of team fouls in a given period (quarter or half) – four for NBA, NCAA women's, and international games – the opposing team is awarded one or two free throws on all subsequent non-shooting fouls for that period, the number depending on the league. In the US college men's game and high school games for both sexes, if a team reaches 7 fouls in a half, the opposing team is awarded one free throw, along with a second shot if the first is made. This is called shooting "one-and-one". If a team exceeds 10 fouls in the half, the opposing team is awarded two free throws on all subsequent fouls for the half.

When a team shoots foul shots, the opponents may not interfere with the shooter, nor may they try to regain possession until the last or potentially last free throw is in the air.

After a team has committed a specified number of fouls, the other team is said to be "in the bonus". On scoreboards, this is usually signified with an indicator light reading "Bonus" or "Penalty" with an illuminated directional arrow or dot indicating that team is to receive free throws when fouled by the opposing team. (Some scoreboards also indicate the number of fouls committed.)

If a team misses the first shot of a two-shot situation, the opposing team must wait for the completion of the second shot before attempting to reclaim possession of the ball and continuing play.

If a player is fouled while attempting a shot and the shot is unsuccessful, the player is awarded a number of free throws equal to the value of the attempted shot. A player fouled while attempting a regular two-point shot thus receives two shots, and a player fouled while attempting a three-point shot receives three shots.

If a player is fouled while attempting a shot and the shot is successful, typically the player will be awarded one additional free throw for one point. In combination with a regular shot, this is called a "three-point play" or "four-point play" (or more colloquially, an "and one") because of the basket made at the time of the foul (2 or 3 points) and the additional free throw (1 point).

Common techniques and practices

Positions

Although the rules do not specify any positions whatsoever, they have evolved as part of basketball. During the early years of basketball's evolution, two guards, two forwards, and one center were used. In more recent times specific positions evolved, but the current trend, advocated by many top coaches including Mike Krzyzewski, is towards positionless basketball, where big players are free to shoot from outside and dribble if their skill allows it.[58] Popular descriptions of positions include:

Point guard (often called the "1") : usually the fastest player on the team, organizes the team's offense by controlling the ball and making sure that it gets to the right player at the right time.

Shooting guard (the "2") : creates a high volume of shots on offense, mainly long-ranged; and guards the opponent's best perimeter player on defense.

Small forward (the "3") : often primarily responsible for scoring points via cuts to the basket and dribble penetration; on defense seeks rebounds and steals, but sometimes plays more actively.

Power forward (the "4"): plays offensively often with their back to the basket; on defense, plays under the basket (in a zone defense) or against the opposing power forward (in man-to-man defense).

Center (the "5"): uses height and size to score (on offense), to protect the basket closely (on defense), or to rebound.

The above descriptions are flexible. For most teams today, the shooting guard and small forward have very similar responsibilities and are often called the wings, as do the power forward and center, who are often called post players. While most teams describe two players as guards, two as forwards, and one as a center, on some occasions teams choose to call them by different designations.

Strategy

There are two main defensive strategies: zone defense and man-to-man defense. In a zone defense, each player is assigned to guard a specific area of the court. Zone defenses often allow the defense to double team the ball, a manoeuver known as a trap. In a man-to-man defense, each defensive player guards a specific opponent.

Offensive plays are more varied, normally involving planned passes and movement by players without the ball. A quick movement by an offensive player without the ball to gain an advantageous position is known as a cut. A legal attempt by an offensive player to stop an opponent from guarding a teammate, by standing in the defender's way such that the teammate cuts next to him, is a screen or pick. The two plays are combined in the pick and roll, in which a player sets a pick and then "rolls" away from the pick towards the basket. Screens and cuts are very important in offensive plays; these allow the quick passes and teamwork, which can lead to a successful basket. Teams almost always have several offensive plays planned to ensure their movement is not predictable. On court, the point guard is usually responsible for indicating which play will occur.

Shooting

Shooting is the act of attempting to score points by throwing the ball through the basket, methods varying with players and situations.

Typically, a player faces the basket with both feet facing the basket. A player will rest the ball on the fingertips of the dominant hand (the shooting arm) slightly above the head, with the other hand supporting the side of the ball. The ball is usually shot by jumping (though not always) and extending the shooting arm. The shooting arm, fully extended with the wrist fully bent, is held stationary for a moment following the release of the ball, known as a follow-through. Players often try to put a steady backspin on the ball to absorb its impact with the rim. The ideal trajectory of the shot is somewhat controversial, but generally a proper arc is recommended. Players may shoot directly into the basket or may use the backboard to redirect the ball into the basket.

The two most common shots that use the above described setup are the set shot and the jump shot. Both are preceded by a crouching action which preloads the muscles and increases the power of the shot. In a set shot, the shooter straightens up and throws from a standing position with neither foot leaving the floor; this is typically used for free throws. For a jump shot, the throw is taken in mid-air with the ball being released near the top of the jump. This provides much greater power and range, and it also allows the player to elevate over the defender. Failure to release the ball before the feet return to the floor is considered a traveling violation.

Another common shot is called the layup. This shot requires the player to be in motion toward the basket, and to "lay" the ball "up" and into the basket, typically off the backboard (the backboard-free, underhand version is called a finger roll). The most crowd-pleasing and typically highest-percentage accuracy shot is the slam dunk, in which the player jumps very high and throws the ball downward, through the basket while touching it.

Another shot that is less common than the layup, is the "circus shot". The circus shot is a low-percentage shot that is flipped, heaved, scooped, or flung toward the hoop while the shooter is off-balance, airborne, falling down or facing away from the basket. A back-shot is a shot taken when the player is facing away from the basket, and may be shot with the dominant hand, or both; but there is a very low chance that the shot will be successful.[59]

A shot that misses both the rim and the backboard completely is referred to as an air ball. A particularly bad shot, or one that only hits the backboard, is jocularly called a brick. The hang time is the length of time a player stays in the air after jumping, either to make a slam dunk, layup or jump shot.

Rebounding

The objective of rebounding is to successfully gain possession of the basketball after a missed field goal or free throw, as it rebounds from the hoop or backboard. This plays a major role in the game, as most possessions end when a team misses a shot. There are two categories of rebounds: offensive rebounds, in which the ball is recovered by the offensive side and does not change possession, and defensive rebounds, in which the defending team gains possession of the loose ball. The majority of rebounds are defensive, as the team on defense tends to be in better position to recover missed shots; for example, about 75% of rebounds in the NBA are defensive.[60]

Passing

A pass is a method of moving the ball between players. Most passes are accompanied by a step forward to increase power and are followed through with the hands to ensure accuracy.

A staple pass is the chest pass. The ball is passed directly from the passer's chest to the receiver's chest. A proper chest pass involves an outward snap of the thumbs to add velocity and leaves the defence little time to react.

Another type of pass is the bounce pass. Here, the passer bounces the ball crisply about two-thirds of the way from his own chest to the receiver. The ball strikes the court and bounces up toward the receiver. The bounce pass takes longer to complete than the chest pass, but it is also harder for the opposing team to intercept (kicking the ball deliberately is a violation). Thus, players often use the bounce pass in crowded moments, or to pass around a defender.

The overhead pass is used to pass the ball over a defender. The ball is released while over the passer's head.

The outlet pass occurs after a team gets a defensive rebound. The next pass after the rebound is the outlet pass.

The crucial aspect of any good pass is it being difficult to intercept. Good passers can pass the ball with great accuracy and they know exactly where each of their other teammates prefers to receive the ball. A special way of doing this is passing the ball without looking at the receiving teammate. This is called a no-look pass.

Another advanced style of passing is the behind-the-back pass, which, as the description implies, involves throwing the ball behind the passer's back to a teammate. Although some players can perform such a pass effectively, many coaches discourage no-look or behind-the-back passes, believing them to be difficult to control and more likely to result in turnovers or violations.

Dribbling

Dribbling is the act of bouncing the ball continuously with one hand and is a requirement for a player to take steps with the ball. To dribble, a player pushes the ball down towards the ground with the fingertips rather than patting it; this ensures greater control.

When dribbling past an opponent, the dribbler should dribble with the hand farthest from the opponent, making it more difficult for the defensive player to get to the ball. It is therefore important for a player to be able to dribble competently with both hands.

Good dribblers (or "ball handlers") tend to keep their dribbling hand low to the ground, reducing the distance of travel of the ball from the floor to the hand, making it more difficult for the defender to "steal" the ball. Good ball handlers frequently dribble behind their backs, between their legs, and switch directions suddenly, making a less predictable dribbling pattern that is more difficult to defend against. This is called a crossover, which is the most effective way to move past defenders while dribbling.

A skilled player can dribble without watching the ball, using the dribbling motion or peripheral vision to keep track of the ball's location. By not having to focus on the ball, a player can look for teammates or scoring opportunities, as well as avoid the danger of having someone steal the ball away from him/her.

Blocking

A block is performed when, after a shot is attempted, a defender succeeds in altering the shot by touching the ball. In almost all variants of play, it is illegal to touch the ball after it is in the downward path of its arc; this is known as goaltending. It is also illegal under NBA and Men's NCAA basketball to block a shot after it has touched the backboard, or when any part of the ball is directly above the rim. Under international rules it is illegal to block a shot that is in the downward path of its arc or one that has touched the backboard until the ball has hit the rim. After the ball hits the rim, it is again legal to touch it even though it is no longer considered as a block performed.

To block a shot, a player has to be able to reach a point higher than where the shot is released. Thus, height can be an advantage in blocking. Players who are taller and playing the power forward or center positions generally record more blocks than players who are shorter and playing the guard positions. However, with good timing and a sufficiently high vertical leap, even shorter players can be effective shot blockers.

Height

At the professional level, most male players are above 6 feet 3 inches (1.91 m) and most women above 5 feet 7 inches (1.70 m). Guards, for whom physical coordination and ball-handling skills are crucial, tend to be the smallest players. Almost all forwards in the top men's pro leagues are 6 feet 6 inches (1.98 m) or taller. Most centers are over 6 feet 10 inches (2.08 m) tall. According to a survey given to all NBA teams, the average height of all NBA players is just under 6 feet 7 inches (2.01 m), with the average weight being close to 222 pounds (101 kg). The tallest players ever in the NBA were Manute Bol and Gheorghe Mureșan, who were both 7 feet 7 inches (2.31 m) tall. At 7 feet 2 inches (2.18 m), Margo Dydek was the tallest player in the history of the WNBA.

The shortest player ever to play in the NBA is Muggsy Bogues at 5 feet 3 inches (1.60 m).[61] Other average-height or relatively short players have thrived at the pro level, including Anthony "Spud" Webb, who was 5 feet 7 inches (1.70 m) tall, but had a 42-inch (1.1 m) vertical leap, giving him significant height when jumping, and Temeka Johnson, who won the WNBA Rookie of the Year Award and a championship with the Phoenix Mercury while standing only 5 feet 3 inches (1.60 m). While shorter players are often at a disadvantage in certain aspects of the game, their ability to navigate quickly through crowded areas of the court and steal the ball by reaching low are strengths.

Players regularly inflate their height in high school or college. Many prospects exaggerate their height while in high school or college to make themselves more appealing to coaches and scouts, who prefer taller players. Charles Barkley stated; "I've been measured at 6–5, 6-4+3⁄4. But I started in college at 6–6." Sam Smith, a former writer from the Chicago Tribune, said: "We sort of know the heights, because after camp, the sheet comes out. But you use that height, and the player gets mad. And then you hear from his agent. Or you file your story with the right height, and the copy desk changes it because they have the 'official' N.B.A. media guide, which is wrong. So you sort of go along with the joke."[62]

Since the 2019-20 NBA season heights of NBA players are recorded definitively by measuring players with their shoes off.[63]

Variations and similar games

Variations of basketball are activities based on the game of basketball, using common basketball skills and equipment (primarily the ball and basket). Some variations only have superficial rule changes, while others are distinct games with varying degrees of influence from basketball. Other variations include children's games, contests or activities meant to help players reinforce skills.

An earlier version of basketball, played primarily by women and girls, was six-on-six basketball. Horseball is a game played on horseback where a ball is handled and points are scored by shooting it through a high net (approximately 1.5m×1.5m). The sport is like a combination of polo, rugby, and basketball. There is even a form played on donkeys known as Donkey basketball, which has attracted criticism from animal rights groups.

Half-court

Perhaps the single most common variation of basketball is the half-court game, played in informal settings without referees or strict rules. Only one basket is used, and the ball must be "taken back" or "cleared" – passed or dribbled outside the three-point line each time possession of the ball changes from one team to the other. Half-court games require less cardiovascular stamina, since players need not run back and forth a full court. Half-court raises the number of players that can use a court or, conversely, can be played if there is an insufficient number to form full 5-on-5 teams.

Half-court basketball is usually played 1-on-1, 2-on-2 or 3-on-3. The latter variation is gradually gaining official recognition as 3x3, originally known as FIBA 33. It was first tested at the 2007 Asian Indoor Games in Macau and the first official tournaments were held at the 2009 Asian Youth Games and the 2010 Youth Olympics, both in Singapore. The first FIBA 3x3 Youth World Championships[64] were held in Rimini, Italy in 2011, with the first FIBA 3x3 World Championships for senior teams following a year later in Athens. The sport is highly tipped to become an Olympic sport as early as 2016.[65] In the summer of 2017, the BIG3 basketball league, a professional 3x3 half court basketball league that features former NBA players, began. The BIG3 features several rule variants including a four-point field goal.[66]

Other variations

Variations of basketball with their own page or subsection include:

- 21 (also known as American, cutthroat and roughhouse)[67]

- 42

- Around the World

- Bounce

- Firing Squad

- Fives

- H-O-R-S-E

- Hotshot

- Knockout

- One-shot conquer

- Steal The Bacon

- Tip-it

- Tips

- "The One"

- Basketball War

- Water basketball

- Beach basketball

- Streetball

- One-on-one is a variation in which two players will use only a small section of the court (often no more than a half of a court) and compete to play the ball into a single hoop. Such games tend to emphasize individual dribbling and ball stealing skills over shooting and team play.

- Dunk Hoops is a variation played on basketball hoops with lowered (under basketball regulation 10 feet) rims. It originated when the popularity of the slam dunk grew and was developed to create better chances for dunks with lowered rims and using altered goaltending rules.

- Unicycle basketball is played using a regulation basketball on a regular basketball court with the same rules, for example, one must dribble the ball while riding. There are a number of rules that are particular to unicycle basketball as well, for example, a player must have at least one foot on a pedal when in-bounding the ball. Unicycle basketball is usually played using 24" or smaller unicycles, and using plastic pedals, both to preserve the court and the players' shins. Popular unicycle basketball games are organized in North America.[68]

Spin-offs from basketball that are now separate sports include:

- Ringball, a traditional South African sport that stems from basketball, has been played since 1907. The sport is now promoted in South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, Lesotho, India, and Mauritius to establish Ringball as an international sport.

- Korfball (Dutch: Korfbal, korf meaning 'basket') started in the Netherlands and is now played worldwide as a mixed-gender team ball game, similar to mixed netball and basketball.

- Netball is a limited-contact team sport in which two teams of seven try to score points against one another by placing a ball through a high hoop. Australia New Zealand champions (so called ANZ Championship) is very famous in Australia and New Zealand as the premier netball league. Formerly played exclusively by women, netball today features mixed-gender competitions.

- Slamball, invented by television writer Mason Gordon, is a full-contact sport featuring trampolines. The main difference from basketball is the court; below the padded rim and backboard are four trampolines set into the floor, which serve to propel players to great heights for slam dunks. The rules also permit some physical contact between the members of the four-player teams. Professional games of Slamball aired on Spike TV in 2002, and the sport has since expanded to China and other countries.

.jpg.webp) A basketball player in Israel, 1969

A basketball player in Israel, 1969 Schoolgirls shooting hoops among the Himalayas in Dharamsala, India.

Schoolgirls shooting hoops among the Himalayas in Dharamsala, India. A basketball training course at the Phan Đình Phùng High School, Hanoi, Vietnam

A basketball training course at the Phan Đình Phùng High School, Hanoi, Vietnam A basketball court in Tamil Nadu, India

A basketball court in Tamil Nadu, India

Social forms of basketball

Basketball as a social and communal sport features environments, rules and demographics different from those seen in professional and televised basketball.

Recreational basketball

Basketball is played widely as an extracurricular, intramural or amateur sport in schools and colleges. Notable institutions of recreational basketball include:

- Basketball schools and academies, where students are trained in developing basketball fundamentals, undergo fitness and endurance exercises and learn various basketball skills. Basketball students learn proper ways of passing, ball handling, dribbling, shooting from various distances, rebounding, offensive moves, defense, layups, screens, basketball rules and basketball ethics. Also popular are the basketball camps organized for various occasions, often to get prepared for basketball events, and basketball clinics for improving skills.

- College and university basketball played in educational institutions of higher learning. This includes National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) intercollegiate basketball.

Disabled basketball

- Deaf basketball: One of several deaf sports, deaf basketball relies on signing for communication. Any deaf sporting event that happens, its purpose is to serve as a catalyst for the socialization of a low-incidence and geographically dispersed population.[69]

- Wheelchair basketball: A sport based on basketball but designed for disabled people in wheelchairs and considered one of the major disabled sports practiced. There is a functional classification system that is used to help determine if the wheelchair basketball player classification system reflects the existing differences in the performance of elite female players. This system gives an analysis of the players' functional resources through field-testing and game observation. During this system's process, players are assigned a score of 1 to 4.5.[70]

Other forms

- Biddy basketball played by minors, sometimes in formal tournaments, around the globe.

- Gay basketball played in LGBTQIA+ communities. The sport is a major event during the Gay Games, World Outgames and EuroGames.

- Midnight basketball, an initiative to curb inner-city crime in the United States and elsewhere by engaging youth in urban areas with sports as an alternative to drugs and crime.

- Rezball, short for reservation ball, is the avid Native American following of basketball, particularly a style of play particular to Native American teams of some areas.

Fantasy basketball

Fantasy basketball was popularized during the 1990s by ESPN Fantasy Sports, NBA.com, and Yahoo! Fantasy Sports. On the model of fantasy baseball and football, players create fictional teams, select professional basketball players to "play" on these teams through a mock draft or trades, then calculate points based on the players' real-world performance.

See also

- Basketball moves

- Basketball National League

- Continental Basketball Association

- Glossary of basketball terms

- Index of basketball-related articles

- List of basketball films

- List of basketball leagues

- Timeline of women's basketball

- ULEB, Union des Ligues Européennes de Basket, in English Union of European Leagues of Basketball

References

Citations

- ↑ Griffiths, Sian (September 20, 2010). "The Canadian who invented basketball". BBC News. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved September 14, 2011.

- ↑ "Most watched sports in the world". March 13, 2022.

- ↑ "The Surge of the NBA's International Viewership and Popularity". Forbes.com. June 14, 2012. Archived from the original on June 18, 2012. Retrieved June 14, 2012.

- ↑ "REVEALED: The world's best paid teams, Man City close in on Barca and Real Madrid". SportingIntelligence.com. May 1, 2012. Archived from the original on June 16, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- ↑ "YMCA International – World Alliance of YMCAs: Basketball : a YMCA Invention". www.ymca.int. Archived from the original on March 14, 2016. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ↑ "The Greatest Canadian Invention". CBC News. Archived from the original on December 3, 2010.

- ↑ Leather Head Naismith Style Lace Up Basketball Archived September 11, 2016, at the Wayback Machine (The New York Times. Retrieved August 28, 2016)

- ↑ Jeep (July 16, 2012). "Passion Drives Creation – Jeep® & USA Basketball". Archived from the original on July 17, 2012 – via YouTube.

- ↑ Inflatable ball, Inventor: Frank Dieterle, Patent: US 1660378 A (1928) Archived November 23, 2016, at the Wayback Machine The description in this patent explains problems caused by lacing on the cover of basketballs.

- ↑ Naismith, James (1941). Basketball : its origin and development. New York: Association Press.

- ↑ "James Naismith Biography". February 14, 2007. Archived from the original on February 5, 2007. Retrieved February 14, 2007.

- ↑ Thinkquest, Basketball. Retrieved January 20, 2009.

- ↑ "Newly found documents shed light on basketball's birth". ESPN.com. November 14, 2006. Retrieved July 29, 2022.

- ↑ "Basketball". olympic.org. June 26, 2010. Archived from the original on September 20, 2009. Retrieved December 18, 2005.

- ↑ "Newly found documents shed light on basketball's birth". ESPN. Associated Press. November 13, 2006. Archived from the original on December 1, 2007. Retrieved January 11, 2007.

- ↑ Fuoco, Linda (April 15, 2010). "Grandson of basketball's inventor brings game's exhibit to Geneva College". Postgazette.com. Archived from the original on October 11, 2011. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- ↑ "Hamline University Athletics: Hutton Arena". Hamline.edu. January 4, 1937. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved July 25, 2010.

- ↑ "1st Ever Public Basketball Game Played..." www.rarenewspapers.com. Archived from the original on March 20, 2016.

- ↑ "1st Ever Public Basketball Game Played". Rare & Early Newspapers. March 12, 1892. Archived from the original on March 20, 2016. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ↑ Queen's Journal, vol. 31, no. 7, February 16, 1904; 105 years of Canadian university basketball, by Earl Zukerman, "broken link". Archived from the original on October 1, 2018. Retrieved February 6, 2009.

- ↑ 2008–09 High School Athletics Participation Survey NFHS.

- ↑ "2016–17 High School Athletics Participation Survey" (PDF). National Federation of State High School Associations. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 25, 2018. Retrieved February 16, 2018.

- ↑ "National Interscholastic Basketball Tournament – hoopedeia.nba.com – Retrieved September 13, 2009". Hoopedia.nba.com. Archived from the original on August 10, 2010. Retrieved July 25, 2010.

- ↑ "National Catholic Interscholastic Basketball Tournament, 1924–1941 – hoopedia.nba.com – Retrieved September 13, 2009". Hoopedia.nba.com. December 7, 1941. Archived from the original on August 10, 2010. Retrieved July 25, 2010.

- ↑ "National Catholic Invitations Basketball Tournament – hoopedia.nba.com – Retrieved September 13, 2009". Hoopedia.nba.com. Archived from the original on August 10, 2010. Retrieved July 25, 2010.

- ↑ "– National Interscholastic Basketball Tournament for Black High Schools, 1929–1942 – Retrieved September 13, 2009". Hoopedia.nba.com. Archived from the original on August 10, 2010. Retrieved July 25, 2010.

- ↑ "National Invitational Interscholastic Basketball Tournament – hoopedia.nba.com – Retrieved September 13, 2009". Hoopedia.nba.com. Archived from the original on August 10, 2010. Retrieved July 25, 2010.

- ↑ Golden, Daniel (July 23, 2012). "Three Seconds at 1972 Olympics Haunt U.S. Basketball". Bloomberg Business Week. Archived from the original on January 9, 2015. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- ↑ "Pioneers in Physical Education". pp. 661–662. Archived from the original on June 20, 2009. Retrieved June 3, 2009.

- 1 2 "Senda Berenson Papers". Archived from the original on February 3, 2016. Retrieved June 3, 2009.

- ↑ Jenkins, Sally. "History of Women's Basketball". WNBA.com. Archived from the original on January 6, 2013. Retrieved January 21, 2014.

- ↑ Peacock-Broyles, Trinity. "You Come in as a Squirrel and Leave as an Owl". Smith.edu. Archived from the original on June 15, 2011. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 "Historical Timeline". Archived from the original on June 21, 2009. Retrieved June 2, 2009.

- ↑ "The Great Teams". Archived from the original on August 12, 2010. Retrieved June 2, 2009.

- ↑ Television New Zealand, BASKETBALL | NBA getting through tough times Archived March 18, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Everything You Need to Know About Basketball Court Dimensions | PROformance Hoops". proformancehoops.com. June 7, 2019. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- 1 2 "Official Rules of the National Basketball Association 2013–2014" (PDF). NBA.com. pp. 8–9. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 12, 2018.

- ↑ "NBA Official Rules 2018–19" (PDF). pp. 29–30. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- ↑ FIBA Official Basketball Rules (2010) Rule 4, Section 8.1 Retrieved July 26, 2010

- ↑ NBA Official Rules (2009–2010) Archived January 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Rule 5, Section II, a. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- 1 2 3 2009–2011 Men's & Women's Basketball Rules Archived August 6, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Rule 5, Section 6, Article 1. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- ↑ "NCAA panel approves women's basketball rules changes". ESPN.com. Associated Press. June 8, 2015. Archived from the original on June 9, 2015. Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Struckhoff, Mary, ed. (2009). 2009–2010 NFHS Basketball Rules. Indianapolis, Indiana: National Federation of High Schools. p. 41. Rule 5, Section 5, Article 1

- ↑ Stewart, Mark (June 25, 2015). "Varsity basketball games will have two 18-minute halves next season". Journal Sentinel. Archived from the original on July 11, 2018. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- ↑ NBA Official Rules (2009–2010) Archived January 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Rule 5, Section II, c. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- ↑ FIBA Official Basketball Rules (2010) Rule 4, Section 8.4 Retrieved July 26, 2010

- ↑ NBA Official Rules (2009–2010) Archived January 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Rule 5, Section II, b. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- ↑ FIBA Official Basketball Rules (2010) Rule 4, Section 8.7 Retrieved July 26, 2010

- ↑ FIBA Official Basketball Rules (2010) Rule 3, Section 4.2.2 Retrieved July 26, 2010

- ↑ NBA Official Rules (2009–2010) Archived January 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Rule 3, Section I, a. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- ↑ 2009–2011 Men's & Women's Basketball Rules Archived August 6, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Rule 10, Section 2, Article 6. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- ↑ Struckhoff, Mary, ed. (2009). 2009–2010 NFHS Basketball Rules. Indianapolis, Indiana: National Federation of High Schools. p. 59. Rule 10, Section 1, Article 6

- ↑ Lynch, William. "What Are the Different Types of Basketball Court Surfaces?". Archived from the original on March 23, 2016. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ↑ "What Are the Different Types of Basketball Court Surfaces?". LIVESTRONG. February 7, 2014. Archived from the original on March 23, 2016. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Official Rules, RULE NO. 1: Court Dimensions – Equipment". National Basketball Association. October 15, 2018.

- ↑ Moniz, Brian (August 28, 2020). "Why Do Basketball Hoops Have Nets?". BasketballWorld.

- ↑ "Wilson to provide the Official Game Ball for FIBA" (Press release). Amer Sports. June 9, 2015. Archived from the original on September 3, 2015. Retrieved August 17, 2015.

- ↑ Marshall, John (November 1, 2014). "Positionless basketball taking hold in college". Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- ↑ "WATCH: Curry pulls off circus shot and gets a foul". ABS-CBN News. November 17, 2016. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ↑ "2022–23 NBA Season Summary". Basketball-Reference.com. Retrieved April 18, 2023.

- ↑ "Muggsy Bogues Bio". NBA.com. Archived from the original on July 17, 2010. Retrieved July 25, 2010.

- ↑ Noah Liberman (June 22, 2008). "When Height Becomes a Tall Tale". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 13, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

- ↑ "For years, some NBA players lied about their height. They can't anymore". Washington Post. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- ↑ "2011 3x3 Youth World Championship". FIBA.com. September 11, 2011. Archived from the original on November 13, 2012. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- ↑ Thomas, Vincent. "3-on-3 basketball might become big time?". ESPN. ESPN Internet Ventures. Archived from the original on February 1, 2013. Retrieved January 11, 2011.

- ↑ AP (June 26, 2017). "Big3 begins: Ice Cube's new 3-on-3 league starts with a bang". USA Today. Gannett. Archived from the original on December 10, 2017. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- ↑ Eric Shanburn (2008). Basketball and Baseball Games: For the Driveway, Field Or the Alleyway. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4343-8912-1. Retrieved June 29, 2010.

- ↑ "Comcast SportsNet Feature about Berkeley Unicycle Basketball". Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ↑ Stewart, David Alan (1991). Deaf Sport: the Impact of Sports within the Deaf Community. Gallaudet University Press. pp. 234. ISBN 9780930323745.

- ↑ Vanlandewijck, Yves C; Evaggelinou, Christina; Daly, Daniel J; Verellen, Joeri; Van Houtte, Siska; Aspeslagh, Vanessa; Hendrickx, Robby; Piessens, Tine; Zwakhoven, Bjorn (December 3, 2003). "The Relationship between Functional Potential and Field Performance in Elite Female Wheelchair Basketball Players". Journal of Sports Sciences. Taylor & Francis. 22 (7): 668–675. doi:10.1080/02640410310001655750. OCLC 23080411. PMID 15370498. S2CID 27418917.

General references

- National Basketball Association (2014). "Official Rules of the National Basketball Association" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- International Basketball Federation (June 2004). Official Basketball Rules. Archived from the original on December 22, 2005.

- Reimer, Anthony (June 2005). "FIBA vs North American Rules Comparison". FIBA Assist (14): 40–44. Archived from the original on January 29, 2009. Retrieved January 11, 2006.

- Bonsor, Kevin (March 10, 2003). "How Basketball Works: Who's Who". HowStuffWorks. Archived from the original on January 1, 2006. Retrieved January 11, 2006.

Further reading

- Adolph H, Grundman (2004). The golden age of amateur basketball: the AAU Tournament, 1921–1968. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-7117-4.

- Batchelor, Bob (2005). Basketball in America: from the playgrounds to Jordan's game and beyond. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7890-1613-3.

- Brown, Donald H (2007). A Basketball Handbook. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4259-6190-9.

- Coleman, Brian (1991). All You Wanted to Know About Basketball. Sterling publishing. ISBN 81-207-2576-X.

- Grundy, Pamela; Susan Shackelford (2005). Shattering the glass: the remarkable history of women's basketball. New Press. ISBN 1-56584-822-5.

- Herzog, Brad (2003). Hoopmania: The Book of Basketball History and Trivia. Rosen Pub. Group. ISBN 0-8239-3697-X.

- Naismith, James (1941). Basketball: its origin and development. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-8370-9.

- Simmons, Bill (2009). The book of basketball: the NBA according to the sports guy. Ballantine/ESPN Books. ISBN 978-0-345-51176-8.

history of Basketball.

External links

| Library resources about Basketball |

Historical

- Basketball Hall of Fame – Springfield, MA

- National Basketball Foundation – runs the Naismith Museum in Ontario

- Hometown Sports Heroes Archived April 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

Organizations

Other sources

- "Basketball". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Basketball at Curlie

- Eurobasket website

- Basketball-Reference.com: Basketball Statistics, Analysis and History Archived February 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Ontario's Historical Plaques – Dr. James Naismith (1861–1939)