| Ashbridge Estate | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | 1444 Queen Street East Toronto, Ontario, Canada |

| Area | 2 acres (0.81 ha) |

| Built | 1796 (this building 1854, second floor added 1900) |

| Architect | Joseph Sheard |

| Website | Ontario Heritage Trust |

The Ashbridge Estate is a historic estate in eastern Toronto, Ontario, Canada. The property was settled by the Ashbridge family, who were English Quakers who left Pennsylvania after the American Revolutionary War. In 1796, as United Empire Loyalists, the family were granted 600 acres (240 ha) of land on Lake Ontario east of the Don River, land which they had begun clearing two years earlier.

The family constructed log cabins and frame homes on the shore of a bay, which was later named for them. The present home was built starting in 1854, with additions in 1900 and 1920. As the city of Toronto grew and encroached on the estate, the family gradually sold off their land, leaving only the current 2-acre (0.81 ha) property by the 1920s.

The estate is located on Queen Street East near Greenwood Avenue in the Leslieville neighbourhood. In 1972, the family donated the estate to the Ontario Heritage Trust, although members of the family continued living in the home until 1997. The site was listed on the Canadian Register of Historic Places in 2008. The Ashbridges are the only family in the history of Toronto to have continuously occupied land that they settled for more than 200 years.

History

The Ashbridge family were English Quakers who lived in Chester County, Pennsylvania in the mid-18th century. Jonathan Ashbridge had been disowned by the Chester Meeting some time after the American Revolutionary War and died in Pennsylvania in 1782.[1]: 308 Jonathan's wife, Sarah, arrived in Upper Canada in 1793 with her two sons, John and Jonathan, three of her daughters, and their families.[2]: 180 Folklore suggests they spent their first winter in the ruins of the old French fort, Fort Rouillé, near present-day Fort York.[3]

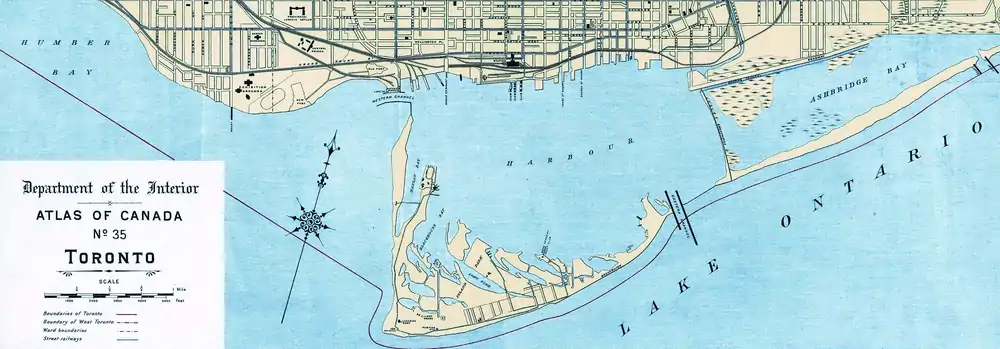

In 1794, the family began clearing land east of present-day Greenwood Avenue on three plots laid out by John Graves Simcoe, on a country trail which became the Kingston Road. As United Empire Loyalists fleeing political persecution in the United States, the family were officially granted 600 acres (240 ha) of the land in 1796, known as Part Lots 7, 8, and 9, stretching from Lake Ontario to present-day Danforth Avenue.[4] A log cabin was built on the trail about 60 m (200 ft) from the shoreline of Lake Ontario, on a bay formed by the mouth of the Don River.[5]: 125 While clearing the land for farming, the family subsisted on fish and waterfowl from the bay and pigs that they raised. The family grew wheat as soon as they were able, which they transported to market. In the winter they sold ice cut from the bay.[3]

Sarah Ashbridge died in 1801.[1] The brothers, John and Jonathan, each married in 1809, and began construction on two-storey frame homes for their families the same year. These houses were completed in 1811, and located west of the present estate.[4] John and Jonathan served as pathmasters of the Kingston Road from 1797 to 1817. Both participated in the War of 1812 and the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837.[2] Jonathan's son, Jesse, inherited Part Lot 9 upon his father's death in 1845.[2]

Jesse Ashbridge house

The house known as the Jesse Ashbridge house was built on the family's land beginning in 1854.[6] The house was designed for Sarah's grandson and Jonathan's son, Jesse Ashbridge, by prominent local architect, Joseph Sheard, who many years later would serve as Mayor of Toronto. The cottage was designed in the Regency style, built with red brick laid in a Flemish bond, with a hipped roof and treillage veranda.[4] Jesse married in 1864 and died in 1874.[2]

As Toronto's suburbs began to encroach on the family's property in the late-1800s, Jesse's wife, Elizabeth, began subdividing the lot in 1893. A second storey in Second Empire style was added to the home in 1900, with a mansard roof, while maintaining the original veranda.[5] The house was built to the east of the old frame home, which was demolished in 1913. Elizabeth continued to live in the home until her death in 1918.[4]

A further addition was designed in 1920 by Elizabeth's son, Wellington, who trained as a civil engineer. This was in the form of a two-storey addition to the house's north wall.[4]

20th century

In the late nineteenth century, waste from livestock operations at the Gooderham and Worts distillery led to increasing pollution in the bay. A cholera outbreak in 1892 led the distillery to implement an improved waste filtration system, under threat of legal action from the City. Engineer E. H. Keating devised a plan to alter the course of the Don River which improved conditions in the river, but the bay remained severely polluted.[7]

Starting in 1912, the Toronto Harbour Commission began the Ashbridge's Bay Reclamation Scheme, the largest infrastructure project in North America up to that time.[7] The bay was drained, and dredging from the Toronto Harbour was used to fill an area from the harbour to the bay, creating the Toronto Port Lands.[5]: 123–124 Only a small portion of the original bay remained, and the home which was once next to the shore was now located some distance away from the water.[5]: 126

As the city of Toronto expanded eastward and encroached on the estate, Elizabeth and Wellington Ashbridge subdivided and sold off much of the family's land for residential subdivisions.[5] The Duke of Connaught Public School (1912) and S.H. Armstrong Community Recreation Centre were built on land that had been the Ashbridges' orchard.[3][8] Woodfield Road, on the east side of the current property, was originally the farm lane going to the fields farther north.[9]: 112

By the 1920s, the property owned by the family had shrunk to the 2 acres (0.81 ha) that now make up the estate. Wellington's daughters, Dorothy Bullen and Elizabeth Burdon, donated the house and remaining property to the Ontario Heritage Trust in 1972, along with a collection of family artifacts.[6] Dorothy, Sarah Ashbridge's great-great-granddaughter, continued living in the house until 1997. The six generations of the Ashbridge family are the only family in the history of Toronto to have retained the same property for more than 200 years.[4]

Present day

A number of localities in the area are named after the Ashbridges. Just to the south of the house is Jonathan Ashbridge Park (named after Sarah's son), while slightly to the east is Sarah Ashbridge Avenue. The bay that marked the southern edge of the property is now known as Ashbridge's Bay, named for John Ashbridge.[3] On the east and north sides of the bay is the large Ashbridge's Bay Park. Ashbridge's Bay Park North, to the north of the bay, is the site of the Ashbridge's Bay Skate Park, opened in 2009. The west side of the bay is the location of the Ashbridge's Bay Wastewater Treatment Plant, Toronto's main sewage treatment plant and the second largest such facility in Canada.[10]

A large willow tree on the estate, planted in 1919 and a well-known feature of the Leslieville neighbourhood, was felled by high winds in 2016.[11]

Historic plaque

The Ontario Heritage Trust plaque on the estate reads: "This property was home to one family for two centuries. Sarah Ashbridge and her family moved here from Pennsylvania and began clearing land in 1794. Two years later they were granted 600 acres (243 hectares) between Ashbridge's Bay and present day Danforth Avenue. The Ashbridges prospered as farmers until Toronto suburbs began surrounding their land in the 1880s. They sold all but this part of their original farm by the 1920s. Donated to the Ontario Heritage Foundation in 1972, it was the family estate until 1997. As they changed from pioneers to farmers to professionals over 200 years on this property, the Ashbridges personified Ontario's development from agricultural frontier to urban industrial society."[12]

See also

References

- 1 2 Drinker, Elizabeth Sandwith (2010). Elaine Crane (ed.). The Diary of Elizabeth Drinker: The Life Cycle of an Eighteenth-Century Woman. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0812206821.

- 1 2 3 4 Adam, Graeme Mercer; Mulvany, Charles Pelham; Robinson, Christopher Blackett (1885). History of Toronto and County of York, Ontario: Biographical notices. Toronto: C. B. Robinson.

- 1 2 3 4 "Ashbridge Houses I and II". Toronto Historical Association. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Jesse Ashbridge House". Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Brown, Ron (2010). From Queenston to Kingston: The Hidden Heritage of Lake Ontario's Shoreline. Toronto: Natural Heritage Books.

- 1 2 "Ashbridge Estate". Ontario Heritage Trust. Queen's Printer for Ontario. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- 1 2 Bonnell, Jennifer (2009). "Ashbridge's Bay". Don River Valley Historical Mapping Project. NiCHE & University of Toronto Libraries. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ↑ "Duke of Connaught Junior and Senior Public School". Toronto District School Board. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ↑ Ashbridge, Wellington Thomas (1912). The Ashbridge Book. Toronto: The Copp, Clark Company.

- ↑ Heffez, Alanah (27 February 2009). "Our sewage plant is unfortunately bigger than yours". Spacing Montreal. Spacing Media.

- ↑ Kwong, Evelyn (29 September 2016). "Beloved 97-year-old weeping willow crashes on Ashbridge's Estate". Toronto Star. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ↑ Brown, Alan. "The Ashbridge Estate". Toronto's Historical Plaques. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

Further reading

- Ontario Heritage Foundation (2000). Down by the Bay: the Story of the Ashbridge Family. Toronto. OCLC 298136336.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Fairfield, George (1998). Ashbridge's Bay: An Anthology of Writings by Those Who Knew and Loved Ashbridge's Bay. Toronto: Toronto Ornithological Club. ISBN 9780969556213. OCLC 41472232.

- Robinson, Janet (1975). A History of Ashbridge's Bay: From Marshland to Industrial District. OCLC 62993003.