| |

| Designer | |

|---|---|

| Bits | 32-bit, 64-bit |

| Introduced | 1985 |

| Design | RISC |

| Type | Register-Register |

| Branching | Condition code, compare and branch |

| Open | Proprietary |

| Introduced | 2011 |

|---|---|

| Version | ARMv8-R, ARMv8-A, ARMv8.1-A, ARMv8.2-A, ARMv8.3-A, ARMv8.4-A, ARMv8.5-A, ARMv8.6-A, ARMv8.7-A, ARMv8.8-A, ARMv8.9-A, ARMv9.0-A, ARMv9.1-A, ARMv9.2-A, ARMv9.3-A, ARMv9.4-A |

| Encoding | AArch64/A64 and AArch32/A32 use 32-bit instructions, T32 (Thumb-2) uses mixed 16- and 32-bit instructions[1] |

| Endianness | Bi (little as default) |

| Extensions | SVE, SVE2, SME, AES, SHA, TME; All mandatory: Thumb-2, Neon, VFPv4-D16, VFPv4; obsolete: Jazelle |

| Registers | |

| General-purpose | 31 × 64-bit integer registers[1] |

| Floating point | 32 × 128-bit registers[1] for scalar 32- and 64-bit FP or SIMD FP or integer; or cryptography |

| Version | ARMv9-R, ARMv9-M, ARMv8-R, ARMv8-M, ARMv7-A, ARMv7-R, ARMv7E-M, ARMv7-M, ARMv6-M |

|---|---|

| Encoding | 32-bit, except Thumb-2 extensions use mixed 16- and 32-bit instructions. |

| Endianness | Bi (little as default) |

| Extensions | Thumb-2, Neon, Jazelle, AES, SHA, DSP, Saturated, FPv4-SP, FPv5, Helium |

| Registers | |

| General-purpose | 15 × 32-bit integer registers, including R14 (link register), but not R15 (PC) |

| Floating point | Up to 32 × 64-bit registers,[2] SIMD/floating-point (optional) |

| Version | ARMv6, ARMv5, ARMv4T, ARMv3, ARMv2 |

|---|---|

| Encoding | 32-bit, except Thumb extension uses mixed 16- and 32-bit instructions. |

| Endianness | Bi (little as default) in ARMv3 and above |

| Extensions | Thumb, Jazelle |

| Registers | |

| General-purpose | 15 × 32-bit integer registers, including R14 (link register), but not R15 (PC, 26-bit addressing in older) |

| Floating point | None |

ARM (stylised in lowercase as arm, formerly an acronym for Advanced RISC Machines and originally Acorn RISC Machine) is a family of RISC instruction set architectures (ISAs) for computer processors. Arm Ltd. develops the ISAs and licenses them to other companies, who build the physical devices that use the instruction set. It also designs and licenses cores that implement these ISAs.

Due to their low costs, low power consumption, and low heat generation, ARM processors are useful for light, portable, battery-powered devices, including smartphones, laptops, and tablet computers, as well as embedded systems.[3][4][5] However, ARM processors are also used for desktops and servers, including the world's fastest supercomputer (Fugaku) from 2020[6] to 2022. With over 230 billion ARM chips produced,[7][8][9] as of 2022, ARM is the most widely used family of instruction set architectures.[10][4][11][12][13]

There have been several generations of the ARM design. The original ARM1 used a 32-bit internal structure but had a 26-bit address space that limited it to 64 MB of main memory. This limitation was removed in the ARMv3 series, which has a 32-bit address space, and several additional generations up to ARMv7 remained 32-bit. Released in 2011, the ARMv8-A architecture added support for a 64-bit address space and 64-bit arithmetic with its new 32-bit fixed-length instruction set.[14] Arm Ltd. has also released a series of additional instruction sets for different rules; the "Thumb" extension adds both 32- and 16-bit instructions for improved code density, while Jazelle added instructions for directly handling Java bytecode. More recent changes include the addition of simultaneous multithreading (SMT) for improved performance or fault tolerance.[15]

History

BBC Micro

Acorn Computers' first widely successful design was the BBC Micro, introduced in December 1981. This was a relatively conventional machine based on the MOS Technology 6502 CPU but ran at roughly double the performance of competing designs like the Apple II due to its use of faster dynamic random-access memory (DRAM). Typical DRAM of the era ran at about 2 MHz; Acorn arranged a deal with Hitachi for a supply of faster 4 MHz parts.[16]

Machines of the era generally shared memory between the processor and the framebuffer, which allowed the processor to quickly update the contents of the screen without having to perform separate input/output (I/O). As the timing of the video display is exacting, the video hardware had to have priority access to that memory. Due to a quirk of the 6502's design, the CPU left the memory untouched for half of the time. Thus by running the CPU at 1 MHz, the video system could read data during those down times, taking up the total 2 MHz bandwidth of the RAM. In the BBC Micro, the use of 4 MHz RAM allowed the same technique to be used, but running at twice the speed. This allowed it to outperform any similar machine on the market.[17]

Acorn Business Computer

1981 was also the year that the IBM Personal Computer was introduced. Using the recently introduced Intel 8088, a 16-bit CPU compared to the 6502's 8-bit design, it offered higher overall performance. Its introduction changed the desktop computer market radically: what had been largely a hobby and gaming market emerging over the prior five years began to change to a must-have business tool where the earlier 8-bit designs simply could not compete. Even newer 32-bit designs were also coming to market, such as the Motorola 68000[18] and National Semiconductor NS32016.[19]

Acorn began considering how to compete in this market and produced a new paper design named the Acorn Business Computer. They set themselves the goal of producing a machine with ten times the performance of the BBC Micro, but at the same price.[20] This would outperform and underprice the PC. At the same time, the recent introduction of the Apple Lisa brought the graphical user interface (GUI) concept to a wider audience and suggested the future belonged to machines with a GUI.[21] The Lisa, however, cost $9,995, as it was packed with support chips, large amounts of memory, and a hard disk drive, all very expensive then.[22]

The engineers then began studying all of the CPU designs available. Their conclusion about the existing 16-bit designs was that they were a lot more expensive and were still "a bit crap",[23] offering only slightly higher performance than their BBC Micro design. They also almost always demanded a large number of support chips to operate even at that level, which drove up the cost of the computer as a whole. These systems would simply not hit the design goal.[23] They also considered the new 32-bit designs, but these cost even more and had the same issues with support chips.[24] According to Sophie Wilson, all the processors tested at that time performed about the same, with about a 4 Mbit/second bandwidth.[25][lower-alpha 1]

Two key events led Acorn down the path to ARM. One was the publication of a series of reports from the University of California, Berkeley, which suggested that a simple chip design could nevertheless have extremely high performance, much higher than the latest 32-bit designs on the market.[26] The second was a visit by Steve Furber and Sophie Wilson to the Western Design Center, a company run by Bill Mensch and his sister, which had become the logical successor to the MOS team and was offering new versions like the WDC 65C02. The Acorn team saw high school students producing chip layouts on Apple II machines, which suggested that anyone could do it.[27][28] In contrast, a visit to another design firm working on modern 32-bit CPU revealed a team with over a dozen members which were already on revision H of their design and yet it still contained bugs.[lower-alpha 2] This cemented their late 1983 decision to begin their own CPU design, the Acorn RISC Machine.[29]

Design concepts

The original Berkeley RISC designs were in some sense teaching systems, not designed specifically for outright performance. To the RISC's basic register-heavy and load/store concepts, ARM added a number of the well-received design notes of the 6502. Primary among them was the ability to quickly serve interrupts, which allowed the machines to offer reasonable input/output performance with no added external hardware. To offer interrupts with similar performance as the 6502, the ARM design limited its physical address space to 64 MB of total addressable space, requiring 26 bits of address. As instructions were 4 bytes (32 bits) long, and required to be aligned on 4-byte boundaries, the lower 2 bits of an instruction address were always zero. This meant the program counter (PC) only needed to be 24 bits, allowing it to be stored along with the eight bit processor flags in a single 32-bit register. That meant that upon receiving an interrupt, the entire machine state could be saved in a single operation, whereas had the PC been a full 32-bit value, it would require separate operations to store the PC and the status flags. This decision halved the interrupt overhead.[30]

Another change, and among the most important in terms of practical real-world performance, was the modification of the instruction set to take advantage of page mode DRAM. Recently introduced, page mode allowed subsequent accesses of memory to run twice as fast if they were roughly in the same location, or "page", in the DRAM chip. Berkeley's design did not consider page mode and treated all memory equally. The ARM design added special vector-like memory access instructions, the "S-cycles", that could be used to fill or save multiple registers in a single page using page mode. This doubled memory performance when they could be used, and was especially important for graphics performance.[31]

The Berkeley RISC designs used register windows to reduce the number of register saves and restores performed in procedure calls; the ARM design did not adopt this.

Wilson developed the instruction set, writing a simulation of the processor in BBC BASIC that ran on a BBC Micro with a second 6502 processor.[32][33] This convinced Acorn engineers they were on the right track. Wilson approached Acorn's CEO, Hermann Hauser, and requested more resources. Hauser gave his approval and assembled a small team to design the actual processor based on Wilson's ISA.[34] The official Acorn RISC Machine project started in October 1983.

ARM1

Acorn chose VLSI Technology as the "silicon partner", as they were a source of ROMs and custom chips for Acorn. Acorn provided the design and VLSI provided the layout and production. The first samples of ARM silicon worked properly when first received and tested on 26 April 1985.[3] Known as ARM1, these versions ran at 6 MHz.[35]

The first ARM application was as a second processor for the BBC Micro, where it helped in developing simulation software to finish development of the support chips (VIDC, IOC, MEMC), and sped up the CAD software used in ARM2 development. Wilson subsequently rewrote BBC BASIC in ARM assembly language. The in-depth knowledge gained from designing the instruction set enabled the code to be very dense, making ARM BBC BASIC an extremely good test for any ARM emulator.

ARM2

The result of the simulations on the ARM1 boards led to the late 1986 introduction of the ARM2 design running at 8 MHz, and the early 1987 speed-bumped version at 10 to 12 MHz.[lower-alpha 3] A significant change in the underlying architecture was the addition of a Booth multiplier, whereas formerly multiplication had to be carried out in software.[37] Further, a new Fast Interrupt reQuest mode, FIQ for short, allowed registers 8 through 14 to be replaced as part of the interrupt itself. This meant FIQ requests did not have to save out their registers, further speeding interrupts.[38]

According to the Dhrystone benchmark, the ARM2 was roughly seven times the performance of a typical 7 MHz 68000-based system like the Amiga or Macintosh SE. It was twice as fast as an Intel 80386 running at 16 MHz, and about the same speed as a multi-processor VAX-11/784 superminicomputer. The only systems that beat it were the Sun SPARC and MIPS R2000 RISC-based workstations.[39] Further, as the CPU was designed for high-speed I/O, it dispensed with many of the support chips seen in these machines; notably, it lacked any dedicated direct memory access (DMA) controller which was often found on workstations. The graphics system was also simplified based on the same set of underlying assumptions about memory and timing. The result was a dramatically simplified design, offering performance on par with expensive workstations but at a price point similar to contemporary desktops.[39]

The ARM2 featured a 32-bit data bus, 26-bit address space and 27 32-bit registers, of which 16 are accessible at any one time (including the PC).[40] The ARM2 had a transistor count of just 30,000,[41] compared to Motorola's six-year-older 68000 model with around 68,000. Much of this simplicity came from the lack of microcode, which represents about one-quarter to one-third of the 68000's transistors, and the lack of (like most CPUs of the day) a cache. This simplicity enabled the ARM2 to have a low power consumption and simpler thermal packaging, through having fewer powered transistors, yet offering better performance than the contemporary, 1987, IBM PS/2 Model 50, which initially utilised an Intel 80286, offering 1.8 MIPS @ 10 MHz, and later in 1987, the 2 MIPS of the PS/2 70, with its Intel 386 DX @ 16 MHz.[42][43]

A successor, ARM3, was produced with a 4 KB cache, which further improved performance.[44] The address bus was extended to 32 bits in the ARM6, but program code still had to lie within the first 64 MB of memory in 26-bit compatibility mode, due to the reserved bits for the status flags.[45]

Advanced RISC Machines Ltd. – ARM6

In the late 1980s, Apple Computer and VLSI Technology started working with Acorn on newer versions of the ARM core. In 1990, Acorn spun off the design team into a new company named Advanced RISC Machines Ltd.,[46][47][48] which became ARM Ltd. when its parent company, Arm Holdings plc, floated on the London Stock Exchange and Nasdaq in 1998.[49] The new Apple–ARM work would eventually evolve into the ARM6, first released in early 1992. Apple used the ARM6-based ARM610 as the basis for their Apple Newton PDA.

Early licensees

In 1994, Acorn used the ARM610 as the main central processing unit (CPU) in their RiscPC computers. DEC licensed the ARMv4 architecture and produced the StrongARM.[50] At 233 MHz, this CPU drew only one watt (newer versions draw far less). This work was later passed to Intel as part of a lawsuit settlement, and Intel took the opportunity to supplement their i960 line with the StrongARM. Intel later developed its own high performance implementation named XScale, which it has since sold to Marvell. Transistor count of the ARM core remained essentially the same throughout these changes; ARM2 had 30,000 transistors,[51] while ARM6 grew only to 35,000.[52]

Market share

In 2005, about 98% of all mobile phones sold used at least one ARM processor.[53] In 2010, producers of chips based on ARM architectures reported shipments of 6.1 billion ARM-based processors, representing 95% of smartphones, 35% of digital televisions and set-top boxes, and 10% of mobile computers. In 2011, the 32-bit ARM architecture was the most widely used architecture in mobile devices and the most popular 32-bit one in embedded systems.[54] In 2013, 10 billion were produced[55] and "ARM-based chips are found in nearly 60 percent of the world's mobile devices".[56]

Licensing

Core licence

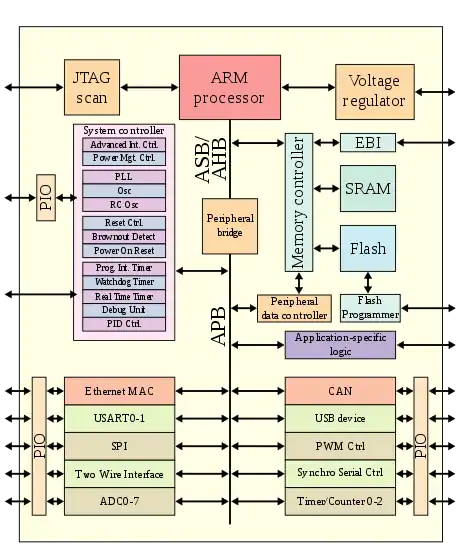

Arm Ltd.'s primary business is selling IP cores, which licensees use to create microcontrollers (MCUs), CPUs, and systems-on-chips based on those cores. The original design manufacturer combines the ARM core with other parts to produce a complete device, typically one that can be built in existing semiconductor fabrication plants (fabs) at low cost and still deliver substantial performance. The most successful implementation has been the ARM7TDMI with hundreds of millions sold. Atmel has been a precursor design center in the ARM7TDMI-based embedded system.

The ARM architectures used in smartphones, PDAs and other mobile devices range from ARMv5 to ARMv8-A.

In 2009, some manufacturers introduced netbooks based on ARM architecture CPUs, in direct competition with netbooks based on Intel Atom.[57]

Arm Ltd. offers a variety of licensing terms, varying in cost and deliverables. Arm Ltd. provides to all licensees an integratable hardware description of the ARM core as well as complete software development toolset (compiler, debugger, software development kit), and the right to sell manufactured silicon containing the ARM CPU.

SoC packages integrating ARM's core designs include Nvidia Tegra's first three generations, CSR plc's Quatro family, ST-Ericsson's Nova and NovaThor, Silicon Labs's Precision32 MCU, Texas Instruments's OMAP products, Samsung's Hummingbird and Exynos products, Apple's A4, A5, and A5X, and NXP's i.MX.

Fabless licensees, who wish to integrate an ARM core into their own chip design, are usually only interested in acquiring a ready-to-manufacture verified semiconductor intellectual property core. For these customers, Arm Ltd. delivers a gate netlist description of the chosen ARM core, along with an abstracted simulation model and test programs to aid design integration and verification. More ambitious customers, including integrated device manufacturers (IDM) and foundry operators, choose to acquire the processor IP in synthesizable RTL (Verilog) form. With the synthesizable RTL, the customer has the ability to perform architectural level optimisations and extensions. This allows the designer to achieve exotic design goals not otherwise possible with an unmodified netlist (high clock speed, very low power consumption, instruction set extensions, etc.). While Arm Ltd. does not grant the licensee the right to resell the ARM architecture itself, licensees may freely sell manufactured products such as chip devices, evaluation boards and complete systems. Merchant foundries can be a special case; not only are they allowed to sell finished silicon containing ARM cores, they generally hold the right to re-manufacture ARM cores for other customers.

Arm Ltd. prices its IP based on perceived value. Lower performing ARM cores typically have lower licence costs than higher performing cores. In implementation terms, a synthesisable core costs more than a hard macro (blackbox) core. Complicating price matters, a merchant foundry that holds an ARM licence, such as Samsung or Fujitsu, can offer fab customers reduced licensing costs. In exchange for acquiring the ARM core through the foundry's in-house design services, the customer can reduce or eliminate payment of ARM's upfront licence fee.

Compared to dedicated semiconductor foundries (such as TSMC and UMC) without in-house design services, Fujitsu/Samsung charge two- to three-times more per manufactured wafer. For low to mid volume applications, a design service foundry offers lower overall pricing (through subsidisation of the licence fee). For high volume mass-produced parts, the long term cost reduction achievable through lower wafer pricing reduces the impact of ARM's NRE (non-recurring engineering) costs, making the dedicated foundry a better choice.

Companies that have developed chips with cores designed by Arm include Amazon.com's Annapurna Labs subsidiary,[58] Analog Devices, Apple, AppliedMicro (now: MACOM Technology Solutions[59]), Atmel, Broadcom, Cavium, Cypress Semiconductor, Freescale Semiconductor (now NXP Semiconductors), Huawei, Intel, Maxim Integrated, Nvidia, NXP, Qualcomm, Renesas, Samsung Electronics, ST Microelectronics, Texas Instruments, and Xilinx.

Built on ARM Cortex Technology licence

In February 2016, ARM announced the Built on ARM Cortex Technology licence, often shortened to Built on Cortex (BoC) licence. This licence allows companies to partner with ARM and make modifications to ARM Cortex designs. These design modifications will not be shared with other companies. These semi-custom core designs also have brand freedom, for example Kryo 280.

Companies that are current licensees of Built on ARM Cortex Technology include Qualcomm.[60]

Architectural licence

Companies can also obtain an ARM architectural licence for designing their own CPU cores using the ARM instruction sets. These cores must comply fully with the ARM architecture. Companies that have designed cores that implement an ARM architecture include Apple, AppliedMicro (now: Ampere Computing), Broadcom, Cavium (now: Marvell), Digital Equipment Corporation, Intel, Nvidia, Qualcomm, Samsung Electronics, Fujitsu, and NUVIA Inc. (acquired by Qualcomm in 2021).

ARM Flexible Access

On 16 July 2019, ARM announced ARM Flexible Access. ARM Flexible Access provides unlimited access to included ARM intellectual property (IP) for development. Per product licence fees are required once a customer reaches foundry tapeout or prototyping.[61][62]

75% of ARM's most recent IP over the last two years are included in ARM Flexible Access. As of October 2019:

- CPUs: Cortex-A5, Cortex-A7, Cortex-A32, Cortex-A34, Cortex-A35, Cortex-A53, Cortex-R5, Cortex-R8, Cortex-R52, Cortex-M0, Cortex-M0+, Cortex-M3, Cortex-M4, Cortex-M7, Cortex-M23, Cortex-M33

- GPUs: Mali-G52, Mali-G31. Includes Mali Driver Development Kits (DDK).

- Interconnect: CoreLink NIC-400, CoreLink NIC-450, CoreLink CCI-400, CoreLink CCI-500, CoreLink CCI-550, ADB-400 AMBA, XHB-400 AXI-AHB

- System Controllers: CoreLink GIC-400, CoreLink GIC-500, PL192 VIC, BP141 TrustZone Memory Wrapper, CoreLink TZC-400, CoreLink L2C-310, CoreLink MMU-500, BP140 Memory Interface

- Security IP: CryptoCell-312, CryptoCell-712, TrustZone True Random Number Generator

- Peripheral Controllers: PL011 UART, PL022 SPI, PL031 RTC

- Debug & Trace: CoreSight SoC-400, CoreSight SDC-600, CoreSight STM-500, CoreSight System Trace Macrocell, CoreSight Trace Memory Controller

- Design Kits: Corstone-101, Corstone-201

- Physical IP: Artisan PIK for Cortex-M33 TSMC 22ULL including memory compilers, logic libraries, GPIOs and documentation

- Tools & Materials: Socrates IP ToolingARM Design Studio, Virtual System Models

- Support: Standard ARM Technical support, ARM online training, maintenance updates, credits toward onsite training and design reviews

Cores

| Architecture | Core bit-width |

Cores | Profile | Refe- rences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arm Ltd. | Third-party | ||||

ARMv1 | ARM1 | Classic | |||

ARMv2 | 32 | ARM2, ARM250, ARM3 | Amber, STORM Open Soft Core[63] | Classic | |

ARMv3 | 32 | ARM6, ARM7 | Classic | ||

ARMv4 | 32 | ARM8 | StrongARM, FA526, ZAP Open Source Processor Core | Classic | |

ARMv4T | 32 | ARM7TDMI, ARM9TDMI, SecurCore SC100 | Classic | ||

ARMv5TE | 32 | ARM7EJ, ARM9E, ARM10E | XScale, FA626TE, Feroceon, PJ1/Mohawk | Classic | |

ARMv6 | 32 | ARM11 | Classic | ||

ARMv6-M | 32 | ARM Cortex-M0, ARM Cortex-M0+, ARM Cortex-M1, SecurCore SC000 | |||

ARMv7-M | 32 | ARM Cortex-M3, SecurCore SC300 | Apple M7 motion coprocessor | Microcontroller | |

ARMv7E-M | 32 | ARM Cortex-M4, ARM Cortex-M7 | Microcontroller | ||

ARMv8-M | 32 | ARM Cortex-M23,[65] ARM Cortex-M33[66] | Microcontroller | ||

ARMv8.1-M |

32 |

ARM Cortex-M55, ARM Cortex-M85 | Microcontroller |

||

ARMv7-R | 32 | ARM Cortex-R4, ARM Cortex-R5, ARM Cortex-R7, ARM Cortex-R8 | |||

ARMv8-R | 32 | ARM Cortex-R52 | Real-time | ||

64 |

ARM Cortex-R82 | Real-time |

|||

ARMv7-A | 32 | ARM Cortex-A5, ARM Cortex-A7, ARM Cortex-A8, ARM Cortex-A9, ARM Cortex-A12, ARM Cortex-A15, ARM Cortex-A17 | Qualcomm Scorpion/Krait, PJ4/Sheeva, Apple Swift (A6, A6X) | ||

ARMv8-A | 32 | ARM Cortex-A32[72] | Application | ||

64/32 | ARM Cortex-A35,[73] ARM Cortex-A53, ARM Cortex-A57,[74] ARM Cortex-A72,[75] ARM Cortex-A73[76] | X-Gene, Nvidia Denver 1/2, Cavium ThunderX, AMD K12, Apple Cyclone (A7)/Typhoon (A8, A8X)/Twister (A9, A9X)/Hurricane+Zephyr (A10, A10X), Qualcomm Kryo, Samsung M1/M2 ("Mongoose") /M3 ("Meerkat") | Application | ||

| ARM Cortex-A34[82] | Application |

||||

ARMv8.1-A | 64/32 | TBA | Cavium ThunderX2 | Application | |

ARMv8.2-A | 64/32 | ARM Cortex-A55,[84] ARM Cortex-A75,[85] ARM Cortex-A76,[86] ARM Cortex-A77, ARM Cortex-A78, ARM Cortex-X1, ARM Neoverse N1 | Nvidia Carmel, Samsung M4 ("Cheetah"), Fujitsu A64FX (ARMv8 SVE 512-bit) | Application | |

64 | ARM Cortex-A65, ARM Neoverse E1 with simultaneous multithreading (SMT), ARM Cortex-A65AE[90] (also having e.g. ARMv8.4 Dot Product; made for safety critical tasks such as advanced driver-assistance systems (ADAS)) | Apple Monsoon+Mistral (A11) (September 2017) | Application | ||

ARMv8.3-A |

64/32 | TBA | Application |

||

64 | TBA | Apple Vortex+Tempest (A12, A12X, A12Z), Marvell ThunderX3 (v8.3+)[91] | Application | ||

ARMv8.4-A | 64/32 | TBA | Application | ||

64 | ARM Neoverse V1 | Apple Lightning+Thunder (A13), Apple Firestorm+Icestorm (A14, M1) | Application | ||

ARMv8.5-A |

64/32 | TBA | Application |

||

64 | TBA | Application |

|||

ARMv8.6-A |

64 | TBA | Apple Avalanche+Blizzard (A15, M2), Apple Everest+Sawtooth (A16)[92] | Application |

|

ARMv8.7-A |

64 | TBA | Application |

||

ARMv8.8-A |

64 |

TBA | Application |

||

ARMv8.9-A |

64 |

TBA | Application |

||

ARMv9.0-A |

64 |

ARM Cortex-A510, ARM Cortex-A710, ARM Cortex-A715, ARM Cortex-X2, ARM Cortex-X3, ARM Neoverse E2, ARM Neoverse N2, ARM Neoverse V2 | Application |

||

ARMv9.1-A |

64 |

TBA | Application |

||

ARMv9.2-A |

64 |

ARM Cortex-A520, ARM Cortex-A720, ARM Cortex-X4 | Application |

||

ARMv9.3-A |

64 |

TBA | Application |

||

ARMv9.4-A |

64 |

TBA | Application |

||

- 1 2 Although most datapaths and CPU registers in the early ARM processors were 32-bit, addressable memory was limited to 26 bits; with upper bits, then, used for status flags in the program counter register.

- 1 2 3 ARMv3 included a compatibility mode to support the 26-bit addresses of earlier versions of the architecture. This compatibility mode optional in ARMv4, and removed entirely in ARMv5.

Arm provides a list of vendors who implement ARM cores in their design (application specific standard products (ASSP), microprocessor and microcontrollers).[98]

Example applications of ARM cores

ARM cores are used in a number of products, particularly PDAs and smartphones. Some computing examples are Microsoft's first generation Surface, Surface 2 and Pocket PC devices (following 2002), Apple's iPads, and Asus's Eee Pad Transformer tablet computers, and several Chromebook laptops. Others include Apple's iPhone smartphones and iPod portable media players, Canon PowerShot digital cameras, Nintendo Switch hybrid, the Wii security processor and 3DS handheld game consoles, and TomTom turn-by-turn navigation systems.

In 2005, Arm took part in the development of Manchester University's computer SpiNNaker, which used ARM cores to simulate the human brain.[99]

ARM chips are also used in Raspberry Pi, BeagleBoard, BeagleBone, PandaBoard, and other single-board computers, because they are very small, inexpensive, and consume very little power.

32-bit architecture

The 32-bit ARM architecture (ARM32), such as Armv7-A (implementing AArch32; see section on Armv8-A for more on it), was the most widely used architecture in mobile devices as of 2011.[54]

Since 1995, various versions of the ARM Architecture Reference Manual (see § External links) have been the primary source of documentation on the ARM processor architecture and instruction set, distinguishing interfaces that all ARM processors are required to support (such as instruction semantics) from implementation details that may vary. The architecture has evolved over time, and version seven of the architecture, ARMv7, defines three architecture "profiles":

- A-profile, the "Application" profile, implemented by 32-bit cores in the Cortex-A series and by some non-ARM cores

- R-profile, the "Real-time" profile, implemented by cores in the Cortex-R series

- M-profile, the "Microcontroller" profile, implemented by most cores in the Cortex-M series

Although the architecture profiles were first defined for ARMv7, ARM subsequently defined the ARMv6-M architecture (used by the Cortex M0/M0+/M1) as a subset of the ARMv7-M profile with fewer instructions.

CPU modes

Except in the M-profile, the 32-bit ARM architecture specifies several CPU modes, depending on the implemented architecture features. At any moment in time, the CPU can be in only one mode, but it can switch modes due to external events (interrupts) or programmatically.[100]

- User mode: The only non-privileged mode.

- FIQ mode: A privileged mode that is entered whenever the processor accepts a fast interrupt request.

- IRQ mode: A privileged mode that is entered whenever the processor accepts an interrupt.

- Supervisor (svc) mode: A privileged mode entered whenever the CPU is reset or when an SVC instruction is executed.

- Abort mode: A privileged mode that is entered whenever a prefetch abort or data abort exception occurs.

- Undefined mode: A privileged mode that is entered whenever an undefined instruction exception occurs.

- System mode (ARMv4 and above): The only privileged mode that is not entered by an exception. It can only be entered by executing an instruction that explicitly writes to the mode bits of the Current Program Status Register (CPSR) from another privileged mode (not from user mode).

- Monitor mode (ARMv6 and ARMv7 Security Extensions, ARMv8 EL3): A monitor mode is introduced to support TrustZone extension in ARM cores.

- Hyp mode (ARMv7 Virtualization Extensions, ARMv8 EL2): A hypervisor mode that supports Popek and Goldberg virtualization requirements for the non-secure operation of the CPU.[101][102]

- Thread mode (ARMv6-M, ARMv7-M, ARMv8-M): A mode which can be specified as either privileged or unprivileged. Whether the Main Stack Pointer (MSP) or Process Stack Pointer (PSP) is used can also be specified in CONTROL register with privileged access. This mode is designed for user tasks in RTOS environment but it is typically used in bare-metal for super-loop.

- Handler mode (ARMv6-M, ARMv7-M, ARMv8-M): A mode dedicated for exception handling (except the RESET which are handled in Thread mode). Handler mode always uses MSP and works in privileged level.

Instruction set

The original (and subsequent) ARM implementation was hardwired without microcode, like the much simpler 8-bit 6502 processor used in prior Acorn microcomputers.

The 32-bit ARM architecture (and the 64-bit architecture for the most part) includes the following RISC features:

- Load–store architecture.

- No support for unaligned memory accesses in the original version of the architecture. ARMv6 and later, except some microcontroller versions, support unaligned accesses for half-word and single-word load/store instructions with some limitations, such as no guaranteed atomicity.[103][104]

- Uniform 16 × 32-bit register file (including the program counter, stack pointer and the link register).

- Fixed instruction width of 32 bits to ease decoding and pipelining, at the cost of decreased code density. Later, the Thumb instruction set added 16-bit instructions and increased code density.

- Mostly single clock-cycle execution.

To compensate for the simpler design, compared with processors like the Intel 80286 and Motorola 68020, some additional design features were used:

- Conditional execution of most instructions reduces branch overhead and compensates for the lack of a branch predictor in early chips.

- Arithmetic instructions alter condition codes only when desired.

- 32-bit barrel shifter can be used without performance penalty with most arithmetic instructions and address calculations.

- Has powerful indexed addressing modes.

- A link register supports fast leaf function calls.

- A simple, but fast, 2-priority-level interrupt subsystem has switched register banks.

Arithmetic instructions

ARM includes integer arithmetic operations for add, subtract, and multiply; some versions of the architecture also support divide operations.

ARM supports 32-bit × 32-bit multiplies with either a 32-bit result or 64-bit result, though Cortex-M0 / M0+ / M1 cores do not support 64-bit results.[105] Some ARM cores also support 16-bit × 16-bit and 32-bit × 16-bit multiplies.

The divide instructions are only included in the following ARM architectures:

- Armv7-M and Armv7E-M architectures always include divide instructions.[106]

- Armv7-R architecture always includes divide instructions in the Thumb instruction set, but optionally in its 32-bit instruction set.[107]

- Armv7-A architecture optionally includes the divide instructions. The instructions might not be implemented, or implemented only in the Thumb instruction set, or implemented in both the Thumb and ARM instruction sets, or implemented if the Virtualization Extensions are included.[107]

Registers

| usr | sys | svc | abt | und | irq | fiq |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R0 | ||||||

| R1 | ||||||

| R2 | ||||||

| R3 | ||||||

| R4 | ||||||

| R5 | ||||||

| R6 | ||||||

| R7 | ||||||

| R8 | R8_fiq | |||||

| R9 | R9_fiq | |||||

| R10 | R10_fiq | |||||

| R11 | R11_fiq | |||||

| R12 | R12_fiq | |||||

| R13 | R13_svc | R13_abt | R13_und | R13_irq | R13_fiq | |

| R14 | R14_svc | R14_abt | R14_und | R14_irq | R14_fiq | |

| R15 | ||||||

| CPSR | ||||||

| SPSR_svc | SPSR_abt | SPSR_und | SPSR_irq | SPSR_fiq | ||

Registers R0 through R7 are the same across all CPU modes; they are never banked.

Registers R8 through R12 are the same across all CPU modes except FIQ mode. FIQ mode has its own distinct R8 through R12 registers.

R13 and R14 are banked across all privileged CPU modes except system mode. That is, each mode that can be entered because of an exception has its own R13 and R14. These registers generally contain the stack pointer and the return address from function calls, respectively.

Aliases:

- R13 is also referred to as SP, the stack pointer.

- R14 is also referred to as LR, the link register.

- R15 is also referred to as PC, the program counter.

The Current Program Status Register (CPSR) has the following 32 bits.[108]

- M (bits 0–4) is the processor mode bits.

- T (bit 5) is the Thumb state bit.

- F (bit 6) is the FIQ disable bit.

- I (bit 7) is the IRQ disable bit.

- A (bit 8) is the imprecise data abort disable bit.

- E (bit 9) is the data endianness bit.

- IT (bits 10–15 and 25–26) is the if-then state bits.

- GE (bits 16–19) is the greater-than-or-equal-to bits.

- DNM (bits 20–23) is the do not modify bits.

- J (bit 24) is the Java state bit.

- Q (bit 27) is the sticky overflow bit.

- V (bit 28) is the overflow bit.

- C (bit 29) is the carry/borrow/extend bit.

- Z (bit 30) is the zero bit.

- N (bit 31) is the negative/less than bit.

Conditional execution

Almost every ARM instruction has a conditional execution feature called predication, which is implemented with a 4-bit condition code selector (the predicate). To allow for unconditional execution, one of the four-bit codes causes the instruction to be always executed. Most other CPU architectures only have condition codes on branch instructions.[109]

Though the predicate takes up four of the 32 bits in an instruction code, and thus cuts down significantly on the encoding bits available for displacements in memory access instructions, it avoids branch instructions when generating code for small if statements. Apart from eliminating the branch instructions themselves, this preserves the fetch/decode/execute pipeline at the cost of only one cycle per skipped instruction.

An algorithm that provides a good example of conditional execution is the subtraction-based Euclidean algorithm for computing the greatest common divisor. In the C programming language, the algorithm can be written as:

int gcd(int a, int b) {

while (a != b) // We enter the loop when a < b or a > b, but not when a == b

if (a > b) // When a > b we do this

a -= b;

else // When a < b we do that (no "if (a < b)" needed since a != b is checked in while condition)

b -= a;

return a;

}

The same algorithm can be rewritten in a way closer to target ARM instructions as:

loop:

// Compare a and b

GT = a > b;

LT = a < b;

NE = a != b;

// Perform operations based on flag results

if (GT) a -= b; // Subtract *only* if greater-than

if (LT) b -= a; // Subtract *only* if less-than

if (NE) goto loop; // Loop *only* if compared values were not equal

return a;

and coded in assembly language as:

; assign a to register r0, b to r1

loop: CMP r0, r1 ; set condition "NE" if (a ≠ b),

; "GT" if (a > b),

; or "LT" if (a < b)

SUBGT r0, r0, r1 ; if "GT" (Greater Than), then a = a − b

SUBLT r1, r1, r0 ; if "LT" (Less Than), then b = b − a

BNE loop ; if "NE" (Not Equal), then loop

B lr ; return

which avoids the branches around the then and else clauses. If r0 and r1 are equal then neither of the SUB instructions will be executed, eliminating the need for a conditional branch to implement the while check at the top of the loop, for example had SUBLE (less than or equal) been used.

One of the ways that Thumb code provides a more dense encoding is to remove the four-bit selector from non-branch instructions.

Other features

Another feature of the instruction set is the ability to fold shifts and rotates into the data processing (arithmetic, logical, and register-register move) instructions, so that, for example, the statement in C language:

a += (j << 2);

could be rendered as a one-word, one-cycle instruction:[110]

ADD Ra, Ra, Rj, LSL #2

This results in the typical ARM program being denser than expected with fewer memory accesses; thus the pipeline is used more efficiently.

The ARM processor also has features rarely seen in other RISC architectures, such as PC-relative addressing (indeed, on the 32-bit[1] ARM the PC is one of its 16 registers) and pre- and post-increment addressing modes.

The ARM instruction set has increased over time. Some early ARM processors (before ARM7TDMI), for example, have no instruction to store a two-byte quantity.

Pipelines and other implementation issues

The ARM7 and earlier implementations have a three-stage pipeline; the stages being fetch, decode, and execute. Higher-performance designs, such as the ARM9, have deeper pipelines: Cortex-A8 has thirteen stages. Additional implementation changes for higher performance include a faster adder and more extensive branch prediction logic. The difference between the ARM7DI and ARM7DMI cores, for example, was an improved multiplier; hence the added "M".

Coprocessors

The ARM architecture (pre-Armv8) provides a non-intrusive way of extending the instruction set using "coprocessors" that can be addressed using MCR, MRC, MRRC, MCRR, and similar instructions. The coprocessor space is divided logically into 16 coprocessors with numbers from 0 to 15, coprocessor 15 (cp15) being reserved for some typical control functions like managing the caches and MMU operation on processors that have one.

In ARM-based machines, peripheral devices are usually attached to the processor by mapping their physical registers into ARM memory space, into the coprocessor space, or by connecting to another device (a bus) that in turn attaches to the processor. Coprocessor accesses have lower latency, so some peripherals—for example, an XScale interrupt controller—are accessible in both ways: through memory and through coprocessors.

In other cases, chip designers only integrate hardware using the coprocessor mechanism. For example, an image processing engine might be a small ARM7TDMI core combined with a coprocessor that has specialised operations to support a specific set of HDTV transcoding primitives.

Debugging

All modern ARM processors include hardware debugging facilities, allowing software debuggers to perform operations such as halting, stepping, and breakpointing of code starting from reset. These facilities are built using JTAG support, though some newer cores optionally support ARM's own two-wire "SWD" protocol. In ARM7TDMI cores, the "D" represented JTAG debug support, and the "I" represented presence of an "EmbeddedICE" debug module. For ARM7 and ARM9 core generations, EmbeddedICE over JTAG was a de facto debug standard, though not architecturally guaranteed.

The ARMv7 architecture defines basic debug facilities at an architectural level. These include breakpoints, watchpoints and instruction execution in a "Debug Mode"; similar facilities were also available with EmbeddedICE. Both "halt mode" and "monitor" mode debugging are supported. The actual transport mechanism used to access the debug facilities is not architecturally specified, but implementations generally include JTAG support.

There is a separate ARM "CoreSight" debug architecture, which is not architecturally required by ARMv7 processors.

Debug Access Port

The Debug Access Port (DAP) is an implementation of an ARM Debug Interface.[111] There are two different supported implementations, the Serial Wire JTAG Debug Port (SWJ-DP) and the Serial Wire Debug Port (SW-DP).[112] CMSIS-DAP is a standard interface that describes how various debugging software on a host PC can communicate over USB to firmware running on a hardware debugger, which in turn talks over SWD or JTAG to a CoreSight-enabled ARM Cortex CPU.[113][114][115]

DSP enhancement instructions

To improve the ARM architecture for digital signal processing and multimedia applications, DSP instructions were added to the set.[116] These are signified by an "E" in the name of the ARMv5TE and ARMv5TEJ architectures. E-variants also imply T, D, M, and I.

The new instructions are common in digital signal processor (DSP) architectures. They include variations on signed multiply–accumulate, saturated add and subtract, and count leading zeros.

SIMD extensions for multimedia

Introduced in the ARMv6 architecture, this was a precursor to Advanced SIMD, also named Neon.[117]

Jazelle

Jazelle DBX (Direct Bytecode eXecution) is a technique that allows Java bytecode to be executed directly in the ARM architecture as a third execution state (and instruction set) alongside the existing ARM and Thumb-mode. Support for this state is signified by the "J" in the ARMv5TEJ architecture, and in ARM9EJ-S and ARM7EJ-S core names. Support for this state is required starting in ARMv6 (except for the ARMv7-M profile), though newer cores only include a trivial implementation that provides no hardware acceleration.

Thumb

To improve compiled code density, processors since the ARM7TDMI (released in 1994[118]) have featured the Thumb instruction set, which have their own state. (The "T" in "TDMI" indicates the Thumb feature.) When in this state, the processor executes the Thumb instruction set, a compact 16-bit encoding for a subset of the ARM instruction set.[119] Most of the Thumb instructions are directly mapped to normal ARM instructions. The space saving comes from making some of the instruction operands implicit and limiting the number of possibilities compared to the ARM instructions executed in the ARM instruction set state.

In Thumb, the 16-bit opcodes have less functionality. For example, only branches can be conditional, and many opcodes are restricted to accessing only half of all of the CPU's general-purpose registers. The shorter opcodes give improved code density overall, even though some operations require extra instructions. In situations where the memory port or bus width is constrained to less than 32 bits, the shorter Thumb opcodes allow increased performance compared with 32-bit ARM code, as less program code may need to be loaded into the processor over the constrained memory bandwidth.

Unlike processor architectures with variable length (16- or 32-bit) instructions, such as the Cray-1 and Hitachi SuperH, the ARM and Thumb instruction sets exist independently of each other. Embedded hardware, such as the Game Boy Advance, typically have a small amount of RAM accessible with a full 32-bit datapath; the majority is accessed via a 16-bit or narrower secondary datapath. In this situation, it usually makes sense to compile Thumb code and hand-optimise a few of the most CPU-intensive sections using full 32-bit ARM instructions, placing these wider instructions into the 32-bit bus accessible memory.

The first processor with a Thumb instruction decoder was the ARM7TDMI. All ARM9 and later families, including XScale, have included a Thumb instruction decoder. It includes instructions adopted from the Hitachi SuperH (1992), which was licensed by ARM.[120] ARM's smallest processor families (Cortex M0 and M1) implement only the 16-bit Thumb instruction set for maximum performance in lowest cost applications.

Thumb-2

Thumb-2 technology was introduced in the ARM1156 core, announced in 2003. Thumb-2 extends the limited 16-bit instruction set of Thumb with additional 32-bit instructions to give the instruction set more breadth, thus producing a variable-length instruction set. A stated aim for Thumb-2 was to achieve code density similar to Thumb with performance similar to the ARM instruction set on 32-bit memory.

Thumb-2 extends the Thumb instruction set with bit-field manipulation, table branches and conditional execution. At the same time, the ARM instruction set was extended to maintain equivalent functionality in both instruction sets. A new "Unified Assembly Language" (UAL) supports generation of either Thumb or ARM instructions from the same source code; versions of Thumb seen on ARMv7 processors are essentially as capable as ARM code (including the ability to write interrupt handlers). This requires a bit of care, and use of a new "IT" (if-then) instruction, which permits up to four successive instructions to execute based on a tested condition, or on its inverse. When compiling into ARM code, this is ignored, but when compiling into Thumb it generates an actual instruction. For example:

; if (r0 == r1)

CMP r0, r1

ITE EQ ; ARM: no code ... Thumb: IT instruction

; then r0 = r2;

MOVEQ r0, r2 ; ARM: conditional; Thumb: condition via ITE 'T' (then)

; else r0 = r3;

MOVNE r0, r3 ; ARM: conditional; Thumb: condition via ITE 'E' (else)

; recall that the Thumb MOV instruction has no bits to encode "EQ" or "NE".

All ARMv7 chips support the Thumb instruction set. All chips in the Cortex-A series, Cortex-R series, and ARM11 series support both "ARM instruction set state" and "Thumb instruction set state", while chips in the Cortex-M series support only the Thumb instruction set.[121][122][123]

Thumb Execution Environment (ThumbEE)

ThumbEE (erroneously called Thumb-2EE in some ARM documentation), which was marketed as Jazelle RCT[124] (Runtime Compilation Target), was announced in 2005 and deprecated in 2011. It first appeared in the Cortex-A8 processor. ThumbEE is a fourth instruction set state, making small changes to the Thumb-2 extended instruction set. These changes make the instruction set particularly suited to code generated at runtime (e.g. by JIT compilation) in managed Execution Environments. ThumbEE is a target for languages such as Java, C#, Perl, and Python, and allows JIT compilers to output smaller compiled code without reducing performance.

New features provided by ThumbEE include automatic null pointer checks on every load and store instruction, an instruction to perform an array bounds check, and special instructions that call a handler. In addition, because it utilises Thumb-2 technology, ThumbEE provides access to registers r8–r15 (where the Jazelle/DBX Java VM state is held).[125] Handlers are small sections of frequently called code, commonly used to implement high level languages, such as allocating memory for a new object. These changes come from repurposing a handful of opcodes, and knowing the core is in the new ThumbEE state.

On 23 November 2011, Arm deprecated any use of the ThumbEE instruction set,[126] and Armv8 removes support for ThumbEE.

Floating-point (VFP)

VFP (Vector Floating Point) technology is a floating-point unit (FPU) coprocessor extension to the ARM architecture[127] (implemented differently in Armv8 – coprocessors not defined there). It provides low-cost single-precision and double-precision floating-point computation fully compliant with the ANSI/IEEE Std 754-1985 Standard for Binary Floating-Point Arithmetic. VFP provides floating-point computation suitable for a wide spectrum of applications such as PDAs, smartphones, voice compression and decompression, three-dimensional graphics and digital audio, printers, set-top boxes, and automotive applications. The VFP architecture was intended to support execution of short "vector mode" instructions but these operated on each vector element sequentially and thus did not offer the performance of true single instruction, multiple data (SIMD) vector parallelism. This vector mode was therefore removed shortly after its introduction,[128] to be replaced with the much more powerful Advanced SIMD, also named Neon.

Some devices such as the ARM Cortex-A8 have a cut-down VFPLite module instead of a full VFP module, and require roughly ten times more clock cycles per float operation.[129] Pre-Armv8 architecture implemented floating-point/SIMD with the coprocessor interface. Other floating-point and/or SIMD units found in ARM-based processors using the coprocessor interface include FPA, FPE, iwMMXt, some of which were implemented in software by trapping but could have been implemented in hardware. They provide some of the same functionality as VFP but are not opcode-compatible with it. FPA10 also provides extended precision, but implements correct rounding (required by IEEE 754) only in single precision.[130]

- VFPv1

- Obsolete

- VFPv2

- An optional extension to the ARM instruction set in the ARMv5TE, ARMv5TEJ and ARMv6 architectures. VFPv2 has 16 64-bit FPU registers.

- VFPv3 or VFPv3-D32

- Implemented on most Cortex-A8 and A9 ARMv7 processors. It is backward-compatible with VFPv2, except that it cannot trap floating-point exceptions. VFPv3 has 32 64-bit FPU registers as standard, adds VCVT instructions to convert between scalar, float and double, adds immediate mode to VMOV such that constants can be loaded into FPU registers.

- VFPv3-D16

- As above, but with only 16 64-bit FPU registers. Implemented on Cortex-R4 and R5 processors and the Tegra 2 (Cortex-A9).

- VFPv3-F16

- Uncommon; it supports IEEE754-2008 half-precision (16-bit) floating point as a storage format.

- VFPv4 or VFPv4-D32

- Implemented on Cortex-A12 and A15 ARMv7 processors, Cortex-A7 optionally has VFPv4-D32 in the case of an FPU with Neon.[131] VFPv4 has 32 64-bit FPU registers as standard, adds both half-precision support as a storage format and fused multiply-accumulate instructions to the features of VFPv3.

- VFPv4-D16

- As above, but it has only 16 64-bit FPU registers. Implemented on Cortex-A5 and A7 processors in the case of an FPU without Neon.[131]

- VFPv5-D16-M

- Implemented on Cortex-M7 when single and double-precision floating-point core option exists.

In Debian Linux and derivatives such as Ubuntu and Linux Mint, armhf (ARM hard float) refers to the ARMv7 architecture including the additional VFP3-D16 floating-point hardware extension (and Thumb-2) above. Software packages and cross-compiler tools use the armhf vs. arm/armel suffixes to differentiate.[132]

Advanced SIMD (Neon)

The Advanced SIMD extension (also known as Neon or "MPE" Media Processing Engine) is a combined 64- and 128-bit SIMD instruction set that provides standardised acceleration for media and signal processing applications. Neon is included in all Cortex-A8 devices, but is optional in Cortex-A9 devices.[133] Neon can execute MP3 audio decoding on CPUs running at 10 MHz, and can run the GSM adaptive multi-rate (AMR) speech codec at 13 MHz. It features a comprehensive instruction set, separate register files, and independent execution hardware.[134] Neon supports 8-, 16-, 32-, and 64-bit integer and single-precision (32-bit) floating-point data and SIMD operations for handling audio and video processing as well as graphics and gaming processing. In Neon, the SIMD supports up to 16 operations at the same time. The Neon hardware shares the same floating-point registers as used in VFP. Devices such as the ARM Cortex-A8 and Cortex-A9 support 128-bit vectors, but will execute with 64 bits at a time,[129] whereas newer Cortex-A15 devices can execute 128 bits at a time.[135][136]

A quirk of Neon in Armv7 devices is that it flushes all subnormal numbers to zero, and as a result the GCC compiler will not use it unless -funsafe-math-optimizations, which allows losing denormals, is turned on. "Enhanced" Neon defined since Armv8 does not have this quirk, but as of GCC 8.2 the same flag is still required to enable Neon instructions.[137] On the other hand, GCC does consider Neon safe on AArch64 for Armv8.

ProjectNe10 is ARM's first open-source project (from its inception; while they acquired an older project, now named Mbed TLS). The Ne10 library is a set of common, useful functions written in both Neon and C (for compatibility). The library was created to allow developers to use Neon optimisations without learning Neon, but it also serves as a set of highly optimised Neon intrinsic and assembly code examples for common DSP, arithmetic, and image processing routines. The source code is available on GitHub.[138]

ARM Helium technology

Helium is the M-Profile Vector Extension (MVE). It adds more than 150 scalar and vector instructions.[139]

Security extensions

TrustZone (for Cortex-A profile)

The Security Extensions, marketed as TrustZone Technology, is in ARMv6KZ and later application profile architectures. It provides a low-cost alternative to adding another dedicated security core to an SoC, by providing two virtual processors backed by hardware based access control. This lets the application core switch between two states, referred to as worlds (to reduce confusion with other names for capability domains), to prevent information leaking from the more trusted world to the less trusted world. This world switch is generally orthogonal to all other capabilities of the processor, thus each world can operate independently of the other while using the same core. Memory and peripherals are then made aware of the operating world of the core and may use this to provide access control to secrets and code on the device.[140]

Typically, a rich operating system is run in the less trusted world, with smaller security-specialised code in the more trusted world, aiming to reduce the attack surface. Typical applications include DRM functionality for controlling the use of media on ARM-based devices,[141] and preventing any unapproved use of the device.

In practice, since the specific implementation details of proprietary TrustZone implementations have not been publicly disclosed for review, it is unclear what level of assurance is provided for a given threat model, but they are not immune from attack.[142][143]

Open Virtualization[144] is an open source implementation of the trusted world architecture for TrustZone.

AMD has licensed and incorporated TrustZone technology into its Secure Processor Technology.[145] Enabled in some but not all products, AMD's APUs include a Cortex-A5 processor for handling secure processing.[146][147][148] In fact, the Cortex-A5 TrustZone core had been included in earlier AMD products, but was not enabled due to time constraints.[147]

Samsung Knox uses TrustZone for purposes such as detecting modifications to the kernel, storing certificates and attestating keys.[149]

TrustZone for Armv8-M (for Cortex-M profile)

The Security Extension, marketed as TrustZone for Armv8-M Technology, was introduced in the Armv8-M architecture. While containing similar concepts to TrustZone for Armv8-A, it has a different architectural design, as world switching is performed using branch instructions instead of using exceptions. It also supports safe interleaved interrupt handling from either world regardless of the current security state. Together these features provide low latency calls to the secure world and responsive interrupt handling. ARM provides a reference stack of secure world code in the form of Trusted Firmware for M and PSA Certified.

No-execute page protection

As of ARMv6, the ARM architecture supports no-execute page protection, which is referred to as XN, for eXecute Never.[150]

Large Physical Address Extension (LPAE)

The Large Physical Address Extension (LPAE), which extends the physical address size from 32 bits to 40 bits, was added to the Armv7-A architecture in 2011.[151]

The physical address size may be even larger in processors based on the 64-bit (Armv8-A) architecture. For example, it is 44 bits in Cortex-A75 and Cortex-A65AE.[152]

Armv8-R and Armv8-M

The Armv8-R and Armv8-M architectures, announced after the Armv8-A architecture, share some features with Armv8-A. However, Armv8-M does not include any 64-bit AArch64 instructions, and Armv8-R originally did not include any AArch64 instructions; those instructions were added to Armv8-R later.

Armv8.1-M

The Armv8.1-M architecture, announced in February 2019, is an enhancement of the Armv8-M architecture. It brings new features including:

- A new vector instruction set extension. The M-Profile Vector Extension (MVE), or Helium, is for signal processing and machine learning applications.

- Additional instruction set enhancements for loops and branches (Low Overhead Branch Extension).

- Instructions for half-precision floating-point support.

- Instruction set enhancement for TrustZone management for Floating Point Unit (FPU).

- New memory attribute in the Memory Protection Unit (MPU).

- Enhancements in debug including Performance Monitoring Unit (PMU), Unprivileged Debug Extension, and additional debug support focus on signal processing application developments.

- Reliability, Availability and Serviceability (RAS) extension.

64/32-bit architecture

Armv8

Armv8-A

Announced in October 2011,[14] Armv8-A (often called ARMv8 while the Armv8-R is also available) represents a fundamental change to the ARM architecture. It adds an optional 64-bit architecture named "AArch64" and the associated new "A64" instruction set. AArch64 provides user-space compatibility with Armv7-A, the 32-bit architecture, therein referred to as "AArch32" and the old 32-bit instruction set, now named "A32". The Thumb instruction set is referred to as "T32" and has no 64-bit counterpart. Armv8-A allows 32-bit applications to be executed in a 64-bit OS, and a 32-bit OS to be under the control of a 64-bit hypervisor.[1] ARM announced their Cortex-A53 and Cortex-A57 cores on 30 October 2012.[74] Apple was the first to release an Armv8-A compatible core in a consumer product (Apple A7 in iPhone 5S). AppliedMicro, using an FPGA, was the first to demo Armv8-A.[153] The first Armv8-A SoC from Samsung is the Exynos 5433 used in the Galaxy Note 4, which features two clusters of four Cortex-A57 and Cortex-A53 cores in a big.LITTLE configuration; but it will run only in AArch32 mode.[154]

To both AArch32 and AArch64, Armv8-A makes VFPv3/v4 and advanced SIMD (Neon) standard. It also adds cryptography instructions supporting AES, SHA-1/SHA-256 and finite field arithmetic.[155] AArch64 was introduced in Armv8-A and its subsequent revision. AArch64 is not included in the 32-bit Armv8-R and Armv8-M architectures.

Armv8-R

Optional AArch64 support was added to the Armv8-R profile, with the first ARM core implementing it being the Cortex-R82.[156] It adds the A64 instruction set.

Armv9

Armv9-A

Announced in March 2021, the updated architecture places a focus on secure execution and compartmentalisation.[157][158]

Arm SystemReady

Arm SystemReady, formerly named Arm ServerReady, is a certification program that helps land the generic off-the-shelf operating systems and hypervisors on to the Arm-based systems from datacenter servers to industrial edge and IoT devices. The key building blocks of the program are the specifications for minimum hardware and firmware requirements that the operating systems and hypervisors can rely upon. These specifications are:

- Base System Architecture (BSA) and the market segment specific supplements (e.g., Server BSA supplement)

- Base Boot Requirements (BBR) and Base Boot Security Requirements (BBR)

These specifications are co-developed by Arm and its partners in the System Architecture Advisory Committee (SystemArchAC).

Architecture Compliance Suite (ACS) is the test tools that help to check the compliance of these specifications. The Arm SystemReady Requirements Specification documents the requirements of the certifications.

This program was introduced by Arm in 2020 at the first DevSummit event. Its predecessor Arm ServerReady was introduced in 2018 at the Arm TechCon event. This program currently includes four bands:

- SystemReady SR: this band is for servers and workstations that support operating systems and hypervisors that expect UEFI, ACPI and SMBIOS interfaces. Windows, Red Hat Enterprise Linux and VMware ESXi-Arm require these interfaces while other Linux and BSD distros can also support.

- SystemReady LS (LinuxBoot System): this band is for servers that hyperscalers use to support Linux operating systems that expect LinuxBoot firmware along with the ACPI and SMBIOS interfaces.

- SystemReady ES (Embedded System): this band is for the industrial edge and IoT devices that support operating systems and hypervisors that expect UEFI, ACPI and SMBIOS interfaces. Windows IoT Enterprise, Red Hat Enterprise Linux and VMware ESXi-Arm require these interfaces while other Linux and BSD distros can also support.

- SystemReady IR (IoT Ready): this band is for the industrial edge and IoT devices that support operating systems that expect UEFI and devicetree interfaces. Embedded Linux (e.g., Yocto) and some Linux/BSD distros (e.g., Fedora, Ubuntu, Debian and OpenSUSE) can also support.

PSA Certified

PSA Certified, formerly named Platform Security Architecture, is an architecture-agnostic security framework and evaluation scheme. It is intended to help secure Internet of Things (IoT) devices built on system-on-a-chip (SoC) processors.[159] It was introduced to increase security where a full trusted execution environment is too large or complex.[160]

The architecture was introduced by Arm in 2017 at the annual TechCon event.[160][161] Although the scheme is architecture agnostic, it was first implemented on Arm Cortex-M processor cores intended for microcontroller use. PSA Certified includes freely available threat models and security analyses that demonstrate the process for deciding on security features in common IoT products.[162] It also provides freely downloadable application programming interface (API) packages, architectural specifications, open-source firmware implementations, and related test suites.[163]

Following the development of the architecture security framework in 2017, the PSA Certified assurance scheme launched two years later at Embedded World in 2019.[164] PSA Certified offers a multi-level security evaluation scheme for chip vendors, OS providers and IoT device makers.[165] The Embedded World presentation introduced chip vendors to Level 1 Certification. A draft of Level 2 protection was presented at the same time.[166] Level 2 certification became a usable standard in February 2020.[167]

The certification was created by PSA Joint Stakeholders to enable a security-by-design approach for a diverse set of IoT products. PSA Certified specifications are implementation and architecture agnostic, as a result they can be applied to any chip, software or device.[168][166] The certification also removes industry fragmentation for IoT product manufacturers and developers.[169]

Operating system support

32-bit operating systems

Historical operating systems

The first 32-bit ARM-based personal computer, the Acorn Archimedes, was originally intended to run an ambitious operating system called ARX. The machines shipped with RISC OS which was also used on later ARM-based systems from Acorn and other vendors. Some early Acorn machines were also able to run a Unix port called RISC iX. (Neither is to be confused with RISC/os, a contemporary Unix variant for the MIPS architecture.)

Embedded operating systems

The 32-bit ARM architecture is supported by a large number of embedded and real-time operating systems, including:

- A2

- Android

- ChibiOS/RT

- Deos

- DRYOS

- eCos

- embOS

- FreeBSD

- FreeRTOS

- INTEGRITY

- Linux

- Micro-Controller Operating Systems

- Mbed

- MINIX 3

- MQX

- Nucleus PLUS

- NuttX

- Operating System Embedded (OSE)

- OS-9[170]

- Pharos[171]

- Plan 9

- PikeOS[172]

- QNX

- RIOT

- RTEMS

- RTXC Quadros

- SCIOPTA[173]

- ThreadX

- TizenRT

- T-Kernel

- VxWorks

- Windows Embedded Compact

- Windows 10 IoT Core

- Zephyr

Mobile device operating systems

The 32-bit ARM architecture is the primary hardware environment for most mobile device operating systems such as:

Formerly, but now discontinued:

- Bada

- Firefox OS

- MeeGo

- Newton OS

- iOS 10 and earlier

- Symbian

- Windows 10 Mobile

- Windows RT

- Windows Phone

- Windows Mobile

Desktop and server operating systems

The 32-bit ARM architecture is supported by RISC OS and by multiple Unix-like operating systems including:

64-bit operating systems

Embedded operating systems

Mobile device operating systems

- Android supports Armv8-A in Android Lollipop (5.0) and later.

- iOS supports Armv8-A in iOS 7 and later on 64-bit Apple SoCs. iOS 11 and later, and iPadOS, only support 64-bit ARM processors and applications.

- Mobian

- PostmarketOS

- Arch Linux ARM

- Manjaro[180]

Desktop and server operating systems

- Support for Armv8-A was merged into the Linux kernel version 3.7 in late 2012.[181] Armv8-A is supported by a number of Linux distributions, such as:

- Support for Armv8-A was merged into FreeBSD in late 2014.[189]

- OpenBSD has Armv8 support as of 2023.[190]

- NetBSD has Armv8 support since early 2018.[191]

- Windows - Windows 10 runs 32-bit "x86 and 32-bit ARM applications",[192] as well as native ARM64 desktop apps;[193][194] Windows 11 runs native ARM64 apps and can also run x86 and x86-64 apps via emulation. Support for 64-bit ARM apps in the Microsoft Store has been available since November 2018.[195]

- macOS has ARM support since late 2020; the first release to support ARM is macOS Big Sur.[196] Rosetta 2 adds support for x86-64 applications but not virtualization of x86-64 computer platforms.[197]

Porting to 32- or 64-bit ARM operating systems

Windows applications recompiled for ARM and linked with Winelib, from the Wine project, can run on 32-bit or 64-bit ARM in Linux, FreeBSD, or other compatible operating systems.[198][199] x86 binaries, e.g. when not specially compiled for ARM, have been demonstrated on ARM using QEMU with Wine (on Linux and more), but do not work at full speed or same capability as with Winelib.

Notes

- ↑ Using 32-bit words, 4 Mbit/second corresponds to 1 MIPS.

- ↑ Available references do not mention which design team this was, but given the timing and known history of designs of the era, it is likely this was the National Semiconductor team whose NS32016 suffered from a large number of bugs.

- ↑ Matt Evans notes that it appears the faster versions were simply binned higher, and appear to have no underlying changes.[36]

See also

- Amber – an open-source ARM-compatible processor core

- AMULET – an asynchronous implementation of the ARM architecture

- Apple silicon

- ARM Accredited Engineer – certification program

- ARM big.LITTLE – ARM's heterogeneous computing architecture

- ARMulator – an instruction set simulator

- Comparison of ARM processors

- Meltdown (security vulnerability)[200]

- Reduced instruction set computer (RISC)

- RISC-V

- Spectre (security vulnerability)

- Unicore – a 32-register architecture based heavily on a 32-bit ARM

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Grisenthwaite, Richard (2011). "ARMv8-A Technology Preview" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 November 2011. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ↑ "Procedure Call Standard for the ARM Architecture" (PDF). Arm Holdings. 30 November 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- 1 2 Wilson, Roger (2 November 1988). "Some facts about the Acorn RISC Machine". Newsgroup: comp.arch. Retrieved 25 May 2007.

- 1 2 Hachman, Mark (14 October 2002). "ARM Cores Climb into 3G Territory". ExtremeTech. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ↑ Turley, Jim (18 December 2002). "The Two Percent Solution". Embedded. Retrieved 14 February 2023.

- ↑ Cutress, Ian (22 June 2020). "New #1 Supercomputer: Fujitsu's Fugaku and A64FX take Arm to the Top with 415 PetaFLOPs". anandtech.com. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ↑ "Arm Partners Have Shipped 200 Billion Chips". Arm (Press release). Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ↑ "Architecting a smart world and powering Artificial Intelligence: ARM". The Silicon Review. 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ↑ "Enabling Mass IoT connectivity as ARM partners ship 100 billion chips". community.arm.com. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

the cumulative deployment of 100 billion chips, half of which shipped in the last four years. [..] why not a trillion or more? That is our target, seeing a trillion connected devices deployed over the next two decades.

- ↑ "MCU Market on Migration Path to 32-bit and ARM-based Devices: 32-bit tops in sales; 16-bit leads in unit shipments". IC Insights. 25 April 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- ↑ Turley, Jim (2002). "The Two Percent Solution". embedded.com.

- ↑ "Arm Holdings eager for PC and server expansion". The Register. 1 February 2011.

- ↑ McGuire-Balanza, Kerry (11 May 2010). "ARM from zero to billions in 25 short years". Arm Holdings. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- 1 2 "ARM Discloses Technical Details of the Next Version of the ARM Architecture" (Press release). Arm Holdings. 27 October 2011. Archived from the original on 1 January 2019. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ↑ "Announcing the ARM Neoverse N1 Platform". community.arm.com. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ↑ Fairbairn, Douglas (31 January 2012). "Oral History of Sophie Wilson" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ↑ Smith, Tony (30 November 2011). "The BBC Micro turns 30". The Register Hardware. Archived from the original on 12 December 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- ↑ Polsson, Ken. "Chronology of Microprocessors". Processortimeline.info. Archived from the original on 9 August 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- ↑ Leedy, Glenn (April 1983). "The National Semiconductor NS16000 Microprocessor Family". Byte. pp. 53–66. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ↑ Evans 2019, 6:00.

- ↑ Manners, David (29 April 1998). "ARM's way". Electronics Weekly. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- ↑ Evans 2019, 5:30.

- 1 2 Evans 2019, 7:45.

- ↑ Evans 2019, 8:30.

- ↑ Sophie Wilson at Alt Party 2009 (Part 3/8). Archived from the original on 11 December 2021.

- ↑ Chisnall, David (23 August 2010). Understanding ARM Architectures. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ↑ Evans 2019, 9:00.

- ↑ Furber, Stephen B. (2000). ARM system-on-chip architecture. Boston: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-67519-6.

- ↑ Evans 2019, 9:50.

- ↑ Evans 2019, 23:30.

- ↑ Evans 2019, 26:00.

- ↑ "ARM Instruction Set design history with Sophie Wilson (Part 3)". 10 May 2015. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 25 May 2020 – via YouTube.

- ↑ "Oral History of Sophie Wilson – 2012 Computer History Museum Fellow" (PDF). Computer History Museum. 31 January 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ↑ Harker, T. (Summer 2009). "ARM gets serious about IP (Second in a two-part series [Associated Editors' View]". IEEE Solid-State Circuits Magazine. 1 (3): 8–69. doi:10.1109/MSSC.2009.933674. ISSN 1943-0590. S2CID 36567166.

- ↑ Evans 2019, 20:30.

- ↑ Evans 2019, 22:00.

- ↑ Evans 2019, 21:30.

- ↑ Evans 2019, 22:0030.

- 1 2 Evans 2019, 14:00.

- ↑ "From one Arm to the next! ARM Processors and Architectures". Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ↑ Levy, Markus. "The History of The ARM Architecture: From Inception to IPO" (PDF). Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ↑ Introducing the Commodore Amiga 3000 (PDF). Commodore-Amiga, Inc. 1991.

- ↑ "Computer MIPS and MFLOPS Speed Claims 1980 to 1996". www.roylongbottom.org.uk. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ↑ Santanu Chattopadhyay (2010). Embedded System Design. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. p. 9. ISBN 978-81-203-4024-4.

- ↑ Richard Murray. "32 bit operation".

- ↑ "ARM Company Milestones". ARM. Archived from the original on 20 April 2015. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ↑ Andrews, Jason (2005). "3 SoC Verification Topics for the ARM Architecture". Co-verification of hardware and software for ARM SoC design. Oxford, UK: Elsevier. pp. 69. ISBN 0-7506-7730-9.

ARM started as a branch of Acorn Computer in Cambridge, England, with the formation of a joint venture between Acorn, Apple and VLSI Technology. A team of twelve employees produced the design of the first ARM microprocessor between 1983 and 1985.

- ↑ Weber, Jonathan (28 November 1990). "Apple to Join Acorn, VLSI in Chip-Making Venture". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

Apple has invested about $3 million (roughly 1.5 million pounds) for a 30% interest in the company, dubbed Advanced Risc Machines Ltd. (ARM) [...]

- ↑ "ARM Corporate Backgrounder" (PDF). ARM. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2006.

- ↑ Montanaro, James; et al. (1997). "A 160-MHz, 32-b, 0.5-W CMOS RISC Microprocessor" (PDF). Digital Technical Journal. 9 (1): 49–62.

- ↑ DeMone, Paul (9 November 2000). "ARM's Race to Embedded World Domination". Real World Technologies. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ↑ "March of the Machines". technologyreview.com. MIT Technology Review. 20 April 2010. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ↑ Krazit, Tom (3 April 2006). "ARMed for the living room". CNET.

- 1 2 Fitzpatrick, J. (2011). "An Interview with Steve Furber". Communications of the ACM. 54 (5): 34–39. doi:10.1145/1941487.1941501.

- ↑ Tracy Robinson (12 February 2014). "Celebrating 50 Billion shipped ARM-powered Chips".

- ↑ Sarah Murry (3 March 2014). "ARM's Reach: 50 Billion Chip Milestone". Archived from the original on 16 September 2015.

- ↑ Brown, Eric (2009). "ARM netbook ships with detachable tablet". Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2009.

- ↑ Peter Clarke (7 January 2016). "Amazon Now Sells Own ARM chips".

- ↑ "MACOM Successfully Completes Acquisition of AppliedMicro" (Press release). 26 January 2017.

- ↑ Frumusanu, Andrei. "ARM Details Built on ARM Cortex Technology License". AnandTech. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- ↑ Cutress, Ian. "ARM Flexible Access: Design the SoC Before Spending Money". AnandTech. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- ↑ "ARM Flexible Access Frequently Asked Questions". ARM. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- ↑ Nolting, Stephan. "STORM CORE Processor System" (PDF). OpenCores. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ↑ ZAP on GitHub

- ↑ "Cortex-M23 Processor". ARM. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ↑ "Cortex-M33 Processor". ARM. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ↑ "ARMv8-M Architecture Simplifies Security for Smart Embedded". ARM. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ↑ Ltd, Arm. "M-Profile Architectures". Arm | The Architecture for the Digital World. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- ↑ "ARMv8-R Architecture". Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ↑ Craske, Simon (October 2013). "ARM Cortex-R Architecture" (PDF). Arm Holdings. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2014. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ↑ Smith, Ryan (20 September 2016). "ARM Announces Cortex-R52 CPU: Deterministic & Safe, for ADAS & More". AnandTech. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ↑ "Cortex-A32 Processor". ARM. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ↑ "Cortex-A35 Processor". ARM. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- 1 2 "ARM Launches Cortex-A50 Series, the World's Most Energy-Efficient 64-bit Processors" (Press release). Arm Holdings. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ↑ "Cortex-A72 Processor". ARM. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ↑ "Cortex-A73 Processor". ARM. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ↑ "ARMv8-A Architecture". Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ↑ "Cavium Thunder X ups the ARM core count to 48 on a single chip". SemiAccurate. 3 June 2014.

- ↑ "Cavium at Supercomputing 2014". Yahoo Finance. 17 November 2014. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ↑ Burt, Jeff (17 November 2014). "Cray to Evaluate ARM Chips in Its Supercomputers". eWeek.

- ↑ "Samsung Announces Exynos 8890 with Cat.12/13 Modem and Custom CPU". AnandTech.

- ↑ "Cortex-A34 Processor". ARM. Retrieved 10 October 2019.