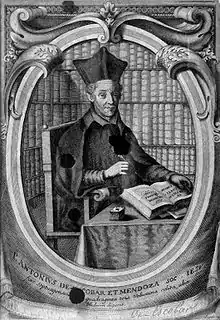

Antonio Escobar y Mendoza (1589 – 4 July 1669) was the leading ethicist of his time.

Biography

Born at Valladolid in Castile, he was educated by Jesuits before entering this order, aged fifteen.[1]

He soon became a famous preacher, and his facility was so great that for fifty years he preached daily, and sometimes twice a day. Above all he was a prodigious writer: his collected works comprise eighty-three volumes. Escobar's first literary efforts were Latin verses in praise of Ignatius Loyola (1613) and Mary (1618), but his principal works focus on exegesis and moral theology. Of the latter the best-known are Summula casuum conscientiae (1627), Liber theologiae moralis (1644) and Universae theologiae moralis problemata (1652–1666).[1] He used to employ the most popular ethical method called casuistry, analyzing real situations rather than strict rules.

Escobar's Summula received criticism, especially in the Jansenist Blaise Pascal's Provincial Letters.[2] Pascal coined the famous maxim that purity of intention may be a justification of actions which are in themselves contrary to the moral code and to human laws, and its general tendency is to find excuses for human weakness.[1] Escobar's doctrines were also disapproved by some Catholics, however he was very appreciated by the mainstream. Molière subjected Escobar to ridicule in his customary witty style, and Escobar was also the target of criticism by Boileau and La Fontaine. By the 18th and in the 19th century, in France the name Escobar had become synonymous with "adroitness in making the rules of morality harmonize with self-interest".[1]

Although Escobar is commented as having followed simple habits in his personal life, being a strict adherent to the rules of the Society of Jesus,[3] it was for his zealous efforts to reform the lives of others he was rebuked. It was said that Escobar "purchased Heaven expensively for himself, but gave it away cheaply to others".[4]

Escobar died at Valladolid in 1669, following which, ten years later, Pope Innocent XI publicly condemned his sixty-five sentences, as well as teachings of other ethical authorities, for being propositiones laxorum moralistarum; nonetheless, it was a criticism towards few judgements and not the scholar in general.[5]

See also

- Alfonso de Aragon y Escobar (1417-1485)

- Diego Hurtado de Mendoza (1468-1536)

- Juan Caramuel y Lobkowitz ("Prince of the Laxists") (1606-1682)

References

- 1 2 3 4 One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Escobar y Mendoza, Antonio". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 765.

- ↑ Franklin, James (2001). The Science of Conjecture: Evidence and Probability Before Pascal. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 97–100. ISBN 0-8018-6569-7.

- ↑ www.britannica.com

- ↑ The Gentleman's Magazine

- ↑ Kelly, J.N.D. 1986. The Oxford history of the popes. Oxford: University Press. ISBN 0-19-282085-0