| Cathedral of Santiago Parish of San José | |

|---|---|

Cathedral of San José, 2007 | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Catholic Church |

| Province | Santiago de Guatemala |

| Rite | Roman Rite |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | cathedral |

| Leadership | Archbishop Cardinal Rodolfo Quezada Toruño |

| Year consecrated | 1541 |

| Status | World Heritage Site |

| Location | |

| Location | Antigua Guatemala, Sacatepéquez |

| Municipality | Antigua Guatemala |

Location in Antigua Guatemala | |

| Territory | Archdiocese of Guatemala |

| Geographic coordinates | 14°33′24″N 90°43′58″W / 14.5567°N 90.7329°W |

| Architecture | |

| Type | church |

Parish of San José (Spanish: Catedral de San José), located in the city of Antigua Guatemala, is part of the Archdiocese of Santiago de Guatemala and is located in a section of the old Primate Cathedral of Antigua Guatemala, which was destroyed by the 1773 Guatemala earthquakes. The first construction of the cathedral began in 1545 with the rubble brought from the destroyed settlement in the Almolonga Valley, which had been a second attempt to found a town in the region. Its complete construction was hampered by frequent earthquakes over the years. On April 7, 1669, the temple was demolished and a second sanctuary would be inaugurated in 1680 under the direction of Juan Pascual and José de Porres, there is also evidence that the Spanish engineer and image maker Martín de Andújar Cantos worked on its reconstruction.

History

Building

The cathedral of Santiago had three constructions; the last of them was consecrated in November 1680 and was the work of master Joseph de Porres. In 1718, after the 1717 Guatemala earthquake (San Miguel earthquakes), Diego de Porres repaired the vaults, the arches, the dome, the second body and the façade.

The main altar stood under a dome, supported by sixteen columns lined with carey and decorated with elaborately worked bronze medallions. On the cornice were placed the image of the Virgin Mary and the twelve Apostles, made of ivory.

In 1743 the Cathedral of Santiago de Guatemala was elevated to Metropolitan, whose festivities were celebrated with great pomp in February 1745.[2] The pallium was brought from Europe by the illustrious Mr. Marín who transported it to Veracruz where he delivered it to Bishop Molina, who was going from road to the city of Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala. Knowing that the bishop was already arriving, the festivities were arranged for the solemn reception and the illustrious dean of the Mitra, the church council, many members of the clergy, the distinguished neighbors and the prelates of the religious came out in carts pulled by mules to receive the visitor.[2]

Arriving at the archbishop's palace, they were received by numerous clerics, schoolboys from the Tridentine College and Seminary of Nuestra Señora de la Asunción. There was a tedeum for the choro chapel of Master Kyrós and then they went to the Palace, where the chapel was richly decorated. Once the ceremony was over, it was decreed that on November 14, 1745, the exaltation festivities would take place.[2]

That day the bells rang early, and numerous rockets were set off.[2] At nine o'clock, the public authorities went to the cathedral, which was decorated with great care and where there was a solemn mass. When the pallium was imposed on Archbishop Pardo y Figueroa, there was a peal of bells and firecrackers and a gunpowder castle in the square in front of the cathedral, followed by a luxurious banquet for the civil and ecclesiastical authorities in the Archbishop's Palace.[2]

The party continued all night, with numerous fireworks. The following days the different regular orders held their own celebration and there were also indigenous and lay dances, horse races and bullfights in the main square for the next eight days.[2]

The archbishop then went to his country house in Milpas Dueñas, where the festivities continued for another week, with bullfights provided by Joseph de Naxera, Joseph de Arrivillaga, and Miguel de Coronado.

The historian Domingo Juarros considers that fifty thousand pesos were spent on those entertainments.[2]

The Santa Marta earthquake of 1773 caused serious damage to the structure of the cathedral, and two of its chapels were restored at the beginning of the 19th century. Beneath the structure is a crypt, in addition to a set of tunnels whose usefulness is unknown.

The cathedral housed the remains of the conqueror Pedro de Alvarado that had been transferred at the request of his daughter in 1568. They were raised during the 1940s and taken to the Peace Court until 1976, when an earthquake forced them to be stored in the Municipality of Antigua Guatemala, where they remained until December 2007, when they returned to the same niche he had occupied in the Cathedral of Antigua Guatemala.[3]

Transfer to the New Guatemala de la Asunción (Guatemala City)

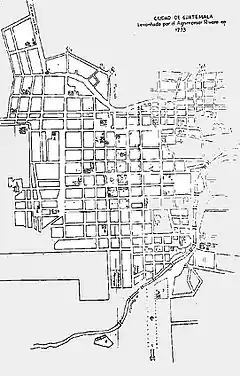

After the earthquakes of 1773, the cathedral was moved to Nueva Guatemala de la Asunción (Guatemala City) on November 22, 1779 and the Parish church of El Sagrario, which also worked on the premises, in May 1780. The altarpieces, furniture and instruments of the old cathedral remained on the premises, but in 1783 they were removed and stored in the building of the University of San Carlos, located in front of the cathedral, and in the sacristy of the Parish El Sagrario. The gigantic walls of the building continued in foot; the interior was used as a cemetery.

Parish of San José

In 1804, Archbishop Peñalver y Cárdenas decided to create the Parish of El Señor San José in Antigua Guatemala, which incorporated three provisional parishes that functioned in the old churches of Candelaria, San Sebastián and Los Remedios. The assets of La Candelaria were transferred to the building of the old University of San Carlos Borromeo, and the abandoned church. The new parish received among the property of Candelaria an image of the Lord of the Descent, which has been venerated in the parish ever since.

In 1806, the priest Rafael José Luna, priest of San José, had the idea of using the ruins of the old cathedral as a parish; in 1814 the ecclesiastical chapter decided to accept the request and in 1819 some remodeling work began on the building, demolishing ruined parts, such as the bell towers. The work stopped for a while, until it was restarted in 1832. When the work was finished, the Parish of San José moved from the old University of San Carlos building to the old cathedral, where it has been ever since.

Earthquake of 1874

According to the American newspaper The New York Times, the earthquake in Guatemala on September 3, 1874 was the most devastating of those recorded in that year throughout the world.[5] Also gangs of outlaws armed with knives and other sharp weapons tried to assault the victims of the region and steal what little they had left; Fortunately, the gangs were captured by the police of the government of General Justo Rufino Barrios and summarily executed.[5]

One witness recounted that the earthquake felt like a combination of a long series of vertical and horizontal movements that made the ground appear to move in waves and rise up to a foot above its normal level.[5] There was US$300,000 in losses; The affected towns apart from Antigua Guatemala, Dueñas, Parramos and Patzicía, were Jocotenango, San Pedro Sacatepéquez and Amatitlán.[5]

The photographer Eadweard Muybridge visited Antigua Guatemala in 1875 and left a photographic record of the state of the city after this earthquake and it can be seen by comparing his photographs with the existing engravings that the parish of San José lost its bell towers.[6]

In 1897, the writer Ariza Poitevín described the conditions in which the ruins of the cathedral were in this way: "there were numerous temples and ruined buildings through whose cracks came out thick roots of the trees that had grown as a result of the abandonment in which the structures were found; The Cathedral could be visited, but with difficulty since it was so neglected that the atmosphere was fetid and humid and night birds and bats abounded, giving the place a gloomy appearance".

20th century

In 1918, after the earthquakes that devastated Guatemala City, Herbert J. Spinden, a correspondent for the American scientific journal National Geographic Magazine, arrived in Guatemala and visited the Cathedral of Antigua Guatemala;[7] Spinden described the state of the cathedral as follows: "The facade of the cathedral faces the central square of the city and hides a large area of destroyed buildings. Through a side door you enter the ruined main nave and pass under the central dome where the pillars are richly adorned with angels and labyrinth-shaped reliefs; or, you can go up to the roof and walk with difficulty on the vegetation that has grown on the beams that join the egg-shaped domes."

Image gallery

.jpg.webp) The Cathedral of Antigua Guatemala in 1894. Photo by Lindesay Brine.[8]

The Cathedral of Antigua Guatemala in 1894. Photo by Lindesay Brine.[8] Front view (1979)

Front view (1979) Night view (2009)

Night view (2009) Decoration for Holy Week (2016)

Decoration for Holy Week (2016) Decoration for Holy Week (2016)

Decoration for Holy Week (2016)

See also

Notes and references

References

- ↑ Nester Mauricio Vásquez Pimentel (2018). Historia del Organismo Judicial (PDF) (1st ed.). Supreme Court of Justice of Guatemala. p. 8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ramón A. Salazar (1897). "Historia del desenvolvimiento intelectual de Guatemala". Tipografía Nacional. p. 278-283, 286.

- ↑ JOSÉ ELÍAS (16 November 2015). "El conquistador "sangriento" no descansa en paz". El País website. Spain.

- ↑ Alfred R. Conkling (1884). Appleton's guide to Mexico, including a chapter on Guatemala, and a complete English-Spanish vocabulary. New York: D. Appleton & Company.

- 1 2 3 4 Earthquakes. A record of the shocks in 1874-the thirty days of terror in Guatemala. 20 December 1874. Archived from the original on 7 December 2015.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ↑ Bruce Bolt (1981). Terremotos. Reverte. p. 43. ISBN 8429146024.

- ↑ Herbert J. Spinden (1919). Shattered capitals of Central America. Vol. 35–36.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Lindesay Brine (1894). Travels amongst American Indians : their ancient earthworks and temples : including a journey in Guatemala, Mexico and Yucatan, and a visit to the ruins of Patinamit, Utatlan, Palenque and Uxmal. London: S. Low, Marston & Company. p. 197.

Further reading

- Antigua Guatemala online (2004). "Arquitectos de Antigua Guatemala". antiguaguatemalaonline.com (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 15 May 2004.

- Cadena, Felipe (1774). Breve descripción de la noble ciudad de Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala y puntual noticia de su lamentable ruina ocasionada de un violento terremoto el día veintinueve de julio de 1773 (PDF) (in Spanish). Mixco, Guatemala: Oficina de Antonio Sánchez Cubillas.

- Conkling, Alfred R. (1884). "Appleton's guide to Mexico, including a chapter on Guatemala, and a complete English-Spanish vocabulary". Nueva York: D. Appleton and Company.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Edición digital multimedia (2005). "La Antigua Guatemala: Catedral". Edición digital multimedia (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 10 August 2011.

- López Medellín, Xavier (n.d.). "Pedro de Alvarado" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 5 December 2004. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- Melchor Toledo, Johann Estuardo (2011). "El arte religioso de la Antigua Guatemala, 1773-1821; crónica de la emigración de sus imágenes" (PDF). Tesis doctoral en Historia del Arte (in Spanish). México, D.F.: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2014. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- Rosales Flores, Martín Haroldo (2015). "Fotos antiguas de la Ciudad de Guatemala: Post conmemorativo". Facebook (in Spanish). Guatemala.

External links

Media related to Catedral de Antigua Guatemala at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Catedral de Antigua Guatemala at Wikimedia Commons