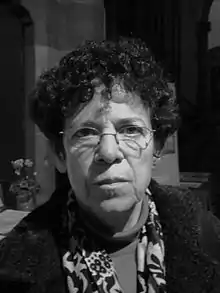

Annette Wieviorka (born January 10, 1948) is a French historian. She is a specialist in the Holocaust and the history of the Jewish people in the 20th century since the 1992 publication of her thesis, Deportation and genocide between memory and forgetting, defended in 1991 at the Paris Nanterre University.[1][2]

Biography

Family

Annette Wieviorka's paternal grandparents, Polish Jews, were arrested in Nice during the war and murdered in Auschwitz. The grandfather, Wolf Wiewiorka, was born on March 10, 1896, in Minsk. The grandmother, Rosa Wiewiorka, née Feldman, was born on August 10, 1897, in Siedlce. Their last address in Nice is at 16 rue Reine Jeanne. They were deported by convoy No. 61, dated October 28, 1943, from Drancy internment camp to Auschwitz. They were detained before at Beaune-la-Rolande internment camp.[3] Her father, a refugee in Switzerland, and her mother, daughter of a Parisian tailor, refugee in Grenoble, survived the war.[4][5] She is the sister of Michel Wieviorka, Sylvie Wieviorka, and Olivier Wieviorka.

Training

Annette Wieviorka has a history (1989) and a doctorate in history (1991). Her thesis, supervised by Annie Kriegel, is entitled Deportation and genocide: oblivion and memory 1943-1948: the case of the Jews in France. This thesis gave rise to a publication in 1992 by Plon.[6] It was reissued in 2003 by Hachette editions.

A committed historian

During the 1970s, she was politically involved in the Maoist movement. From 1974 to 1976, she was a professor of French language and civilization in Canton.

She is involved with the Primo Levi Center (care and support for victims of torture and political violence) as a member of its support committee.[7]

Academic career

Research director at the CNRS,[8] she was a member of the Study Mission on the Spoliation of Jews in France, known as the Mattéoli Mission.[9]

Accolades

Wieviorka was awarded the 2022 Prix Femina essai for Tombeaux : autobiographie de ma famille.[10]

Publications

- L'Écureuil de Chine, Paris, Les presses d'aujourd'hui, 1979 (livre de souvenirs autobiographiques sur son séjour en Chine de 1974 à 1976 - wiewiórka means "squirrel" in Polish) ISBN 2070293017

- Ils étaient juifs, résistants, communistes, Denoël, 1986

- Le procès de Nuremberg, Ouest-France/Mémorial de Caen, Rennes, Paris, 1995 ISBN 2737315778

- avec Jean-Jacques Becker (dir.), Les Juifs de France, Éditions Liana Levi, « Histoire », 1998 ISBN 2867461812

- Auschwitz expliqué à ma fille, Éditions du Seuil, Paris, 1999 ISBN 2020366991

- L'Ère du témoin, Hachette, « Pluriel », Paris, 2002. ISBN 2012790461

- Déportation et génocide. Entre la mémoire et l'oubli, Hachette, « Pluriel », Paris, 2003.

- Auschwitz, 60 ans après, Robert Laffont, Paris, 2005 ISBN 2221102983

Également publié sous le titre Auschwitz, la mémoire d'un lieu, Hachette, « Pluriel », Paris, 2006 ISBN 2012793029 - Juifs et Polonais : 1939 à nos jours, Albin Michel, coll. « Bibliothèque histoire », Paris, 2009 ISBN 9782226187055

- Maurice et Jeannette. Biographie du couple Thorez, Fayard, Paris, 2010 ISBN 9782213654485 compte rendu de l'ouvrage

- Eichmann de la Traque au Procès, André Versaille, Bruxelles, 2011 ISBN 9782874951398. Également publié sous le titre Le Procès Eichmann, Complexe, « La Mémoire du Siècle », Bruxelles, 1989

- L'Heure d'exactitude ; Histoire, mémoire, témoignage, (Entretiens avec Séverine Nikel), Albin Michel, 2011 ISBN 978-2-226-20894-1

- Nouvelles perspectives sur la Shoah, PUF, Paris, 2013, 128 p. ISBN 9782130619277.

- 1945, La découverte, Seuil, Paris, janvier 2015, 282 p. ISBN 978-2-02-118263-7.

- avec Sylvie Lindeperg (dir.), Le moment Eichmann, Albin Michel, 2016 ISBN 978-2-22-631502-1

- avec Danièle Voldman, Tristes grossesses : l'affaire des époux Bac (1953-1956), Paris, Le Seuil, 2019.

Filmography

- Le procès d'Adolf Eichmann [The Trial of Adolf Eichmann] (1997), written by Annette Wieviorka and Michaël Prazan, directed by Michaël Prazan.

- 14 récits d'Auschwitz [14 Stories from Auschwitz] (2002), a documentary series proposed by Annette Wieviorka, creator and writer, with Henri Borlant, directed by Caroline Roulet.

This documentary was produced in conjunction with Annette Wieviorka's participation in a program of the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies of Yale University.[11] - Témoignages pour Mémoire [Testimony for Memory] (2007), written by Annette Wieviorka, Geneviève Decrop, Claudine Drame, and Régine Waintrater (English translation by Ruth Rachel Anderson-Avraham, also a producer on the project), directed by Claudine Drame.

- Le procès d'Adolf Eichmann [The Trial of Adolf Eichmann] (2011) (Infrarouge), written by Annette Wieviorka and Michaël Prazan, directed by Michaël Prazan.

References

- ↑ SUDOC 012150304

- ↑ "Annette Wieviorka".

- ↑ Voir, Klarsfeld, 2012.

- ↑ "Annette Wieviorka". Archived from the original on 2014-03-23. Retrieved 2020-12-01.

- ↑ Marie-Françoise Masson (5 October 2007). "Annette Wieviorka, historienne au nom de ses grands-parents". La Croix. La Croix. Retrieved 26 April 2016..

- ↑ « Déportation et génocide : oubli et mémoire 1943-1948 : le cas des juifs en France », sur theses.fr.

- ↑ "Organigramme de l'Association Primo Levi". Archived from the original on 2012-03-21. Retrieved 2020-12-01.

- ↑ "IRICE - Wieviorka Annette". irice.univ-paris1.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 2017-09-23. Retrieved 2017-07-24.

- ↑ art Astro, Alan. "Annette Wieviorka." Jewish Women : A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia. 1 March 2009. Jewish Women's Archive

- ↑ Dupuy, Éric (7 November 2022). "Claudie Hunzinger, Rachel Cusk et Annette Wieviorka primées au Femina 2022". Livres Hebdo (in French). Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ↑ Séverine Nikel, Annette Wieviorka, L'Heure d'exactitude ; Histoire, mémoire, témoignage, Albin Michel, 2011, ISBN 9782226208941, emplacement 2239-2280 of 3600. Citing the French Wikipedia page for Annette Wieviorka, in English translation: "[Here, one notes Annette Wieviorka's sentiment of ambivalence as a histoirian in respect of these testimonies of survivors of the Shoah, of which certain have a character which is 'so imprecise, dare we say it, and sometimes fanciful', while others, 'on the other hand, are exceptional and sometimes permit those who have told their story for the first time, like Stanislaw Tomkiewicz or Henri Borlant to undertake the writing of a book'; Annette Wieviorka emphasizes their importance 'for the survivors and also their descendants']".