Ali Wallace (fl. 1840-1907) was the name used for a Malay from Sarawak, who accompanied and assisted Alfred Russel Wallace in his travels and explorations from 1855 to 1862. Initially recruited as a cook for his expedition, Ali was later responsible for independently collecting many significant specimens that are credited to Wallace. He also made observations of the birds and the people which were communicated to Wallace. It has been estimated that Ali collected and prepared nearly 5,150 bird specimens. Many of his specimens survive in collections of natural history museums.

Travels with Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace travelled to the Malay archipelago in March 1854 along with his collecting assistant Charles Martin Allen (1839–92). During his travels he hired as many as 1200 people at various points of time and in various places. Among them some made an impression on him and were credited in his writings.[1] When they arrived in Singapore on 18 April 1854, Wallace hired a Malay boy named Ali. He described him:[2]

When I was at Sarawak in 1855 I engaged a Malay boy named Ali as a personal servant, and also to help me to learn the Malay language by the necessity of constant communication with him. He was attentive and clean, and could cook very well. He soon learnt to shoot birds, to skin them properly, and latterly even to put up the skins very neatly. Of course he was a good boatman, as are all Malays, and in all the difficulties or dangers of our journeys he was quite undisturbed and ready to do anything required of him. He accompanied me through all my travels, sometimes alone, but more frequently with several others, and was then very useful in teaching them their duties, as he soon became well acquainted with my wants and habits.

Ali later became an expert at shooting and skinning birds. He accompanied Wallace and Allen and became one his most trusted servants, alongside two other young boys, named Baderoon and Baso.[3]

Ali accompanied Wallace to New Guinea in 1858 before returning to Ternate. Ali collected an ivory-breasted pitta (described as Pitta gigas) for Wallace from Dodinga in early 1858.[4] On Batchian, on 24 August 1858, Ali went to collect birds while Wallace collected insects. Wallace wrote:[5]

Just as I got home I overtook Ali returning from shooting with some birds hanging from his belt. He seemed much pleased, and said, "Look here, sir, what a curious bird," holding out what at first completely puzzled me. I saw a bird with a mass of splendid green feathers on its breast, elongated into two glittering tufts; but, what I could not understand was a pair of long white feathers, which stuck straight out from each shoulder. Ali assured me that the bird stuck them out this way itself, when fluttering its wings, and that they had remained so without his touching them. I now saw that I had got a great prize, no less than a completely new form of the Bird of Paradise, differing most remarkably from every other known bird.

The species was named by George Robert Gray as Semioptera wallacii or Wallace's standardwing.[5]

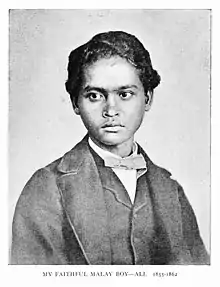

While at Ternate, Ali married a woman and he did not join Wallace in 1859. Ali joined Wallace again in 1861 on a trip to the island of Bouru. In 1862 Wallace went to Singapore where he began preparations to return home to England. Here he provided Ali with money, guns, ammunition and various supplies. Wallace had him photographed and in his 1905 book notes:[2]

He here, for the first time, adopted European clothes, which did not suit him nearly so well as his native dress, and thus clad a friend took a very good photograph of him. I therefore now present his likeness to my readers as that of the best native servant I ever had, and the faithful companion of almost all my journeyings among the islands of the far East.

Life after Wallace

In 1907 American herpetologist Thomas Barbour was in Ternate and he noted in his 1943 memoir:[6]

I was stopped in the street one day as my wife and I were preparing to climb up to the Crater Lake. With us were Ah Woo with his butterfly net, Indit and Bandoung, our well-trained Javanese collectors, with shotguns, cloth bags, and a vasculum for carrying the birds. We were stopped by a wizened old Malay man. I can see him now, with a faded blue fez on his head. He said, "I am Ali Wallace". I knew at once that there stood before me Wallace's faithful companion of many years, the boy who not only helped him collect but nursed him when he was sick. We took his photograph and sent it to Wallace when we got home. He wrote me a delightful letter acknowledging it and reminiscing over the time when Ali had saved his life, nursing him through a terrific attack of malaria.

A 2015 analysis by John van Wyhe and Gerrell M. Drawhorn noted that Ali was more than just a working assistant but that he truly immersed himself into the study of birds.[5] Searching for Ali Wallace, a documentary film, was produced in 2016.

References

- ↑ Wyhe, John van (2018). "Wallace's Help: The Many People Who Aided A. R. Wallace in the Malay Archipelago" (PDF). Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 91 (314): 41–68. doi:10.1353/ras.2018.0003. S2CID 201769115.

- 1 2 Wallace, Alfred Russell (1905). My life : a record of events and opinions. Vol 1. p. 382-3. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ↑ Wallace, Alfred Russel (1890). The Malay Archipelago (PDF). London: Macmillan & Co. p. 312. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ↑ Baker, D.B. (2001). "Alfred Russel Wallace's record of his consignments to Samuel Stevens, 1854-1861" (PDF). Zool. Med. Leiden. 75 (16): 251–341.

- 1 2 3 Wyhe, John Van; Drawhorn, Gerrell M. (2015). "'I am Ali Wallace': The Malay Assistant of Alfred Russel Wallace" (PDF). Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 88: 3–31. doi:10.1353/ras.2015.0012. S2CID 159453047.

- ↑ Barbour, Thomas (1944). Naturalist at Large. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. p. 42.

External links

- Talk by John van Wyhe

- van Wyhe, John (16 October 2017). "'I am Ali Wallace', the Malay assistant of Alfred Russel Wallace: an excerpt". The Conversation.

- "Searching for Ali Wallace: A Film" Archived 2019-11-12 at the Wayback Machine. The Alfred Russel Wallace Website.