The Algerian Green Dam refers to a project initiated in Algeria in the 1960s to plant millions of trees to stop desertification, specifically to prevent the northward advancement of the Sahara Desert.[1]

The project has progressed and evolved through the 1970s, 80s, 90s, and into the 2000s.

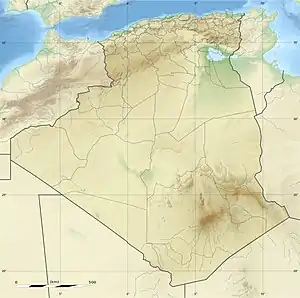

The green barrier is located in the pre-Saharan area in Algeria. It stretches between the Moroccan border in the West to the Tunisian border in the East, covering a total distance of approximately 1000 km.

The barrier's width ranges from approximately 20 km between isohyets of 300 mm in the North and 200 mm in the South of Algeria. The project's objective is to recover the extent of the already existing forest to stop the sand expansion. Two types of vegetation were planted: Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis), which grows easily in this region, and Alfa (Stipa tenacissima).[2][3]

History

The risk of desertification threatens arid and semi-arid regions throughout the world. Population growth, urbanization, an increase in cultivated land areas, overgrazing, and deforestation adding to the effects of climate change exacerbate the issues. Alfa grass cover has decreased while the quality of the grasslands itself is becoming increasingly degraded. According to the UNCCD, recurring droughts and human activities, mainly overgrazing, are the two main driving factors of desertification (Le Houérou, 1996 [4]).

To mitigate this risk, the Algerian authorities developed the Green Dam Project as a massive reforestation program aiming to safeguard and develop the pre-Saharan areas.

Of the 238 million hectares that make up the total land area of Algeria, 200 million are natural deserts, 20 million represent the steppe regions threatened by desertification, and 12 million are mountainous areas threatened by water erosion. 7 million hectares of the 20 steppe regions are highly susceptible to desertification and require a short-term intervention. Several natural factors, like a decrease in rainfall, high thermal amplitude, and dry winds, combined with anthropogenic factors like, cultivation, mechanization, over-grazing, and deforestation accelerate desertification.

With the rapid degradation of Alfa grass steppe, the need for action became more pressing [5]

The late President of Algeria, Houari Boumedien, set up the Green Dam Project. The objective was to establish a 'barrier' of forest spanning the country from east to west in order to halt desertification. The project was halted after his death, but subsequently, the project was relaunched in 1971. [6]

Causes of desertification

The process of deforestation and desertification has disputed origins.

Land use

As early as 1866, French settlers were complaining to the French Government about arson by indigenous Algerians opposed to French rule[7] This perspective was fed by a wider background drawing on both enlightenment thought as well as evidence of environmental degradation in the colonies and during the French Revolution, early conservationists sincerely believed that Mediterranean pastoralism posed a real and severe ecological threat. They blamed pastoralists for deforestation and its perceived environmental and social consequences.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, concern over deforestation was limited to a few disparate voices, and it was dealt with in a handful of laws that were rarely enforced. However, this environmental perspective soon joined forces with political, social, and cultural biases against pastoralism to create a forceful anti-pastoral lobby.[8]

Counter arguments suggest that blaming the indigenous inhabitants for the degradation and subsequent desertification of the landscape, in spite of a lack of evidence that this was the cause, was a Colonial trope to suggest that the original population were incapable of managing their own land and to justify the goals of the Colonia project.[9]

Human factors such as poor agricultural practices are still cited as primary causes of forest fires and deforestation[10][11]

The War for Independence

Similarly, the bombing of forests during the French colonial area has also been cited as a cause of deforestation.

As in previous wars, the guerrillas were almost exclusively based in the mountains of northern Algeria, where the forest and scrub cover were well-suited to guerrilla warfare. Colonel Gilles Martin describes War in Algeria: The French Experience "Vast, mountainous, woody, and lightly populated, Algeria offered terrain favourable to guerrilla warfare." In attempts to tackle the issue of forest cover being used by guerrillas French forces bombed and used napalm to reduce the cover available. [12]

Climate change

Yet another cause, often cited more recently, is climate change. [13][14]

"Although Algeria has experienced a gradual decline in rainfall since 1975, the frequency of floods has increased, which has led to increased costs and damages.

According to PreventionWeb, Algeria ranks 18 of 184 of the most exposed countries to drought. An estimated 3,763,800 (about 10%) of its population is exposed to droughts.

Algeria experienced a record heat wave in June 2003, with temperatures over 40°C for 20 consecutive days that resulted in an estimated 40 deaths. Such events are projected to increase in a warming climate."[15]

Complex causes

Contemporary research has demonstrated that the Sahara is not expanding, as is still frequently believed, but that it expands and contracts based almost entirely on rainfall. [16][17]

Other studies have found that the causes are more complex and that the climate context of North Africa was very similar some 3000 years ago to that of today.[18] [19]

Objectives

The main objective of the Green Dam is to combat desertification. After a few years of implementation, the program developed into a multi-sector project, including:[1]

- Protection and enhancement of existing forest re-sources

- Recovery of missing forest stand• Reforestation

- Development of agricultural and pastoral land

- Fight against sand encroachment and for dune fixation

- Resource mobilization in surface and groundwater

- improvement of accessibility to desertification prone areas

Implementation

The program of the Green Dam has been implemented in four distinct stages:

- From 1970 to 1982, soil restoration and protection groups (SRPG) were formed and assigned to the military regions in a way to cover the entire area of the Green Dam.

- Between 1970 and 1979, seven Groups of the National Service (GNS) were formed. Following an evaluation of the GNS from 1979 to 1982, which aimed to address problems in the forestry sector, groups of forestry (GF) were established within the GNS. During this period, the emphasis was on reforestation and infrastructure development. The reforestation efforts were carried out using the Aleppo pine.•

- Between 1982 and 1990, an inter-ministerial agreement was established to facilitate cooperation between the project owner (such as the State Secretary of Forests) and the project implementer (the High Commission of National Service). Their respective roles were clearly defined with regards to organization, control, financing, and protection of the forest heritage. After evaluating the achievements of this period, gaps were gradually overcome and improvements were made by diversifying restoration activities, such as opening tracks and protecting against soil erosion, and introducing new species such as Cypress, Acacia, and Atriplex.•

- From 1990 to 1993, the Department of Defense withdrew from the Green Dam project, leaving the National Forestry Agency to oversee its implementation. From 1994 to 2000, the government revitalized the Green Dam project by launching a new program in November 1994.[1]

Problems, criticism

In 2021, a scientific study published its findings on the Algerian Green Dam, which highlighted several reasons for its deterioration. The study concluded that current planning to restore the Green Dam should diversify approaches to address these issues.[2]

The study, titled "Monitoring the Spatiotemporal Evolution of the Green Dam in Djelfa Province, Algeria,"[20] examined changes in land degradation and desertification (LDD) and their impact on Moudjbara plantations from 1972 to 2019. Using freely available data such as Landsat imagery and geographic information systems, the study found that while the Green Dam project was effective for a few years, pine plantations underwent significant deterioration afterwards.

The degradation was attributed to forest clearing, livestock overgrazing, and the proliferation of the pine caterpillar processionary.

These factors have destroyed much of the reforestation. The study predicted that, should the degradation continue at the same rate, the green dam project will disappear during the next few decades, in the analyzed region.

For effective control of LDD in Algeria, the study concluded that, in order to move the project forward successfully:

- The institutional approach has to be reviewed and science has to play a more important role in guiding policies.

- The authorities should care about what people want and what nature needs. The focus only on tree planting often does not serve the livelihood demands of the local people.

- The use of this practice (tree planting) as a key approach to stop the encroachment of sand on dryland where trees do not naturally grow, and where shrubs or grass are the native and natural land, needs to be reviewed since woody vegetation encroachment could affect the functioning of this fragile ecosystems. Scientific research has demonstrated that natural recovery is much more effective in restoring degraded arid steppes

- Moving away from the singular tree planting focus to diversifying desertification control methods and adopting the application of dune stabilization methods (including mechanical, chemical and biological methods) is effective in reducing sand and dust storms

- The implementation of sustainable grazing management practices, such as "grazing exclusion", is necessary to enable the natural recovery of the degraded steppes.

The entire approach of the Green Dam Project has been called into question.

Diana K. Davis in her article Desert 'wastes' of the Maghreb: desertification narratives in French colonial environmental history of North Africa argues that the Green Dam Project is based on the false premise created by "French colonial administrators, scientists and settlers which utilised a negative vision of Maghrebi pastoralists as deforesters and desertifiers of the former granary of Rome to justify and facilitate many of their actions."

By claiming that what the French "encountered when they arrived in Algeria was an environment ruined by centuries of burning an overgrazing by the local Algerians, a justification for curtailing local actions was created" and that "Founded on historical inaccuracies, and environmental misunderstandings and exaggerations, the environmental narrative was constructed early in the nineteenth century, primarily in Algeria, and included all of the Maghreb", effectively a misdiagnosis of the problem, has led to the wrong conclusions as to the cure.

"This colonial environmental narrative became entrenched in many official publications such as histories and botanical treatises, as well as agricultural and forestry manuals written during the colonial period" This "laid the foundation for much subsequent education, research, policy and practice".

She suggests that "Its (the colonial narrative) persistence defies convincing evidence that most of North been desertified by burning and overgrazing, for the region was probably forested during the last 3 000 years. Far from being questioned" - the colonial environmental narrative appears to be the dominant postcolonial environmental history. It is particularly strong in policies, and projects concerning desertification"

"The spectre of desertification in North Africa, couched in ideology and language concerning deforestation and desertification disturbingly similar to that used years ago, continues to drive inappropriate environmental projects today" One, among many others that remain to be examined, is the green dam. "This has had a very low rate of tree survival and is considered an ecological failure" [21]

Restorative action

Becoming aware of the threat to the green dam, the General Directorate of Forests (DGF) is currently planning to reforest more than 1.2 million ha in the region, under the latest rural renewal policy, by introducing new principles related to sustainable development, fighting desertification, and climate change adaptation. Having learnt lessons from former programs, the DGF has barred plantations with monospecific stands.[22]

A Government meeting chaired by Prime Minister Abdelaziz Djerad adopted a draft executive decree on the creation of a coordination body in charge of reviving the Green Dam and fighting desertification and is conceived as a catalyst in the development, implementation and assessment. The draft decree, presented by the Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development, provides for the creation of a permanent mechanism responsible for the preparation, implementation and ongoing monitoring of this operation.

In addition to combating desertification, the Algerian Government has presented this initiative as a fight against poverty, through the protection of natural resources, adaptation to climate change, integrated rural development and the promotion of the forestry economy for the benefit of sustainable domestic development as the basis of food security.[23]

Speaking at Echaab daily forum about environmental challenges on the occasion of the World Day to Combat Desertification (WDCD- 17 June), the Minister of Environment and Renewable Energy, Fatima Zohra Zerouati, affirmed that the increasing danger of desertification required new scientific and technical mechanisms to revive the Green Dam and fight against desertification. [24]

The launch of the National Reforestation Plan in 2000 has given the forestry sector a new lease of life with a vision that incorporates the productive aspect of reforestation, the industrial aspect, and the recreational aspect.[25]

As of 2021, the government of Algeria was still planning a restoration effort that is to last several years and involve an investment of $128 million.[26]

See also

- Three-North Shelter Forest Program, a Chinese anti-desertification program started in 1978

- The Great Green Wall of Aravalli, a 1,600 km long and 5 km wide green ecological corridor of India

- The Great Hedge of India, a historic inland customs border

- The Great Green Wall for the Sahara and the Sahel International tree foundation

Bibliography

Mostephaoui. T, Merdas. S, Sakaa. B, Hanafi. M. T, and Be-nazzouz. M. T. (2013): Cartographie des risques d'érosion hy-drique par l'application de l'Equation universelle de pertes ensol à l'aide d'un Système d'Information Géographique dans lebassin versant d'El Hamel (Boussaâda). Journal Algérien desRégions Arides, Numéro Spécial, 12: 131-147

Salemkour.N, Benchouk. K, Nouasria.D, Chefrour.A, Hamou.K,Amechkouh.A, and Belhamra. m. (2013): Effets de la miseen repos sur les caractéristiques floristiques et pastorales desparcours steppiquesde la région de Laghouat (Algérie). Jour-nal Algérien des Régions Arides, Numéro Spécial, 12: 103-114

Kherief Nacereddine.S, Nouasria.D, Salemkour.N, Benchouk. K,and Belhamra.M. (2013): La mise en repos: une technique degestion des parcours steppiques). Journal Algérien des Ré-gions Arides, Numéro Spécial, 12: 115-123

Direction Générale des Forêts (DGF). (2004): Rapport nationalde l'Algérie sur la mise en oeuvre de la Convention de LueContre la Désertification

Le Houérou, H. N. (1996): Climate change, drought and desertification. Journal of Arid Environments, 34: 133–185

Verón, S. R., Paruelo, J. M., & Oesterheld, M. (2006). Assessing desertification. Journal of Arid Environments, 66(4), 751–763.doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2006.01.021

Bensaid, S. (2005). Bilan critique du barrage vert en Algérie.Sécheresse, 6: 247-255. URL http://www.dgf.gov.dz/index.php?rubrique=actualite§ion=dix (13 October 2014)

C. J. Tucker H. E. Dregne and W. W. Newcomb, 'Expansion and contraction of the Sahara desert from 1980 to 1990', Science 253 (1991), pp. 299-301

S. E. Nicholson, C. J. Tucker and M. B. Ba, 'Desertification, drought, and surface vegetation: an example from the west African sahel', Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 79 (1998), pp. 815-29.

J.-L. Ballais, 'Aeolian activity, desertification and the "green dam" in the Ziban Range, Algeria',

A.C. Millington and K. Pye, eds, Environmental change in drylands: biogeographical and geomorphological perspectives (New York, Wiley, 1994), pp. 177-98.

References

- 1 2 3 Merdas, Saifi; Boulghobra, Nouar; Mostephaoui, Tewfik; Belhamra, Mohamed; Fadlaoui, Haroun (2019-07-12). "Assessing land use change and moving sand transport in the western Hodna basin (central Algerian steppe ecosystems)". Forestist. 69 (2): 87–96. doi:10.26650/forestist.2019.19005. ISSN 2602-4039. S2CID 199101182.

- 1 2 Benhizia, Ramzi; Kouba, Yacine; Szabó, György; Négyesi, Gábor; Ata, Behnam (January 2021). "Monitoring the Spatiotemporal Evolution of the Green Dam in Djelfa Province, Algeria". Sustainability. 13 (14): 7953. doi:10.3390/su13147953. hdl:2437/325701. ISSN 2071-1050.

- ↑ Mihi, Ali; Ghazela, Rabeh; wissal, Daoud (August 2022). "Mapping potential desertification-prone areas in North-Eastern Algeria using logistic regression model, GIS, and remote sensing techniques". Environmental Earth Sciences. 81 (15): 385. Bibcode:2022EES....81..385M. doi:10.1007/s12665-022-10513-7. ISSN 1866-6280. PMC 9305054. PMID 35891927.

- ↑ Le Houérou, Henry N. (October 1996). "Climate change, drought and desertification". Journal of Arid Environments. 34 (2): 133–185. Bibcode:1996JArEn..34..133L. doi:10.1006/jare.1996.0099.

- ↑ Belhouadjeb, Fathi Abdellatif; Boumakhleb, Abdallah; Toaiba, Abdelhalim; Doghbage, Abdelghafour; Habib, Benbader; Boukerker, Hassen; Murgueitio, Enrique; Soufan, Walid; Almadani, Mohamad Isam; Daoudi, Belkacem; Khadoumi, Amar (2022-06-20). "The Forage Plantation Program between Desertification Mitigation and Livestock Feeding: An Economic Analysis". Land. 11 (6): 948. doi:10.3390/land11060948. ISSN 2073-445X.

- ↑ UNEP, Samsung Engineering and. "Green Dam in Algeria - Ambassador report - Our Actions - Tunza Eco Generation". tunza.eco-generation.org. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ↑ Sivak, Henry (2013-10-01). "Legal Geographies of Catastrophe: Forests, Fires, and Property in Colonial Algeria". Geographical Review. 103 (4): 556–574. Bibcode:2013GeoRv.103..556S. doi:10.1111/j.1931-0846.2013.00020.x. ISSN 0016-7428. S2CID 143407311.

- ↑ https://repository.library.georgetown.edu/bitstream/handle/10822/559490/Williams_georgetown_0076D_12355.pdf?sequence=1

- ↑ Davis, Diana K. (October 2004). "Desert 'wastes' of the Maghreb: desertification narratives in French colonial environmental history of North Africa". Cultural Geographies. 11 (4): 359–387. Bibcode:2004CuGeo..11..359D. doi:10.1191/1474474004eu313oa. ISSN 1474-4740. S2CID 144825912.

- ↑ Meddour-Sahar, O.; Meddour, R.; Leone, V.; Lovreglio, R.; Derridj, A. (2013). "Analysis of forest fires causes and their motivations in northern Algeria: the Delphi method". IForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry. 6 (5): 247. doi:10.3832/ifor0098-006. ISSN 1971-7458.

- ↑ Belaroui, Karima; Djediai, Houria; Megdad, Hanane (2014-03-21). "The influence of soil, hydrology, vegetation and climate on desertification in El-Bayadh region (Algeria)". Desalination and Water Treatment. 52 (10–12): 2144–2150. Bibcode:2014DWatT..52.2144B. doi:10.1080/19443994.2013.782571. ISSN 1944-3994.

- ↑ Sait, Farid (2021-02-04). "Algerians Reject French Colonial Report, Demand Apology From Macron". Zenger News. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ↑ "Climate change in Algeria". Caritas. 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ↑ "Chapter 3 : Desertification — Special Report on Climate Change and Land". Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ↑ "World Bank Climate Change Knowledge Portal". climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ↑ Helldén, Ulf (1991). "Desertification: Time for an Assessment?". Ambio. 20 (8): 372–383. ISSN 0044-7447. JSTOR 4313868.

- ↑ Tucker, Compton J.; Dregne, Harold E.; Newcomb, Wilbur W. (1991-07-19). "Expansion and Contraction of the Sahara Desert from 1980 to 1990". Science. 253 (5017): 299–300. Bibcode:1991Sci...253..299T. doi:10.1126/science.253.5017.299. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17794695. S2CID 2961273.

- ↑ Barker, Graeme (January 2002). "A tale of two deserts: Contrasting desertification histories on Rome's desert frontiers". World Archaeology. 33 (3): 488–507. doi:10.1080/00438240120107495. ISSN 0043-8243. S2CID 162136132.

- ↑ Heimann, P.; Miosga, H.; Neddermeyer, H. (1979-03-19). "Occupied Surface-State Bands in<mml:math xmlns:mml="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML" display="inline"><mml:mi>sp</mml:mi></mml:math>Gaps of Au(112), Au(110), and Au(100) Faces". Physical Review Letters. 42 (12): 801–804. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.42.801. ISSN 0031-9007.

- ↑ Benhizia, Ramzi; Kouba, Yacine; Szabó, György; Négyesi, Gábor; Ata, Behnam (2021). "Monitoring the Spatiotemporal Evolution of the Green Dam in Djelfa Province, Algeria". Sustainability. 13 (14): 7953. doi:10.3390/su13147953. hdl:2437/325701. ISSN 2071-1050.

- ↑ Ballais, Jean-Louis (1994). "Aeolian Activity, Desertification and the 'Green Dam' in the Ziban Range, Algeria". John Wiley & Sons: 177.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Algerie Presse Service (Algiers)". All Africa. 1 July 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ↑ "Government approves creation of body in charge of reviving Green Dam". Algeria Press Service. 1 July 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ↑ "Desertification: Algeria to revive Green Dam with new technical mechanisms". Algeria Press Service. 19 June 2018. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ↑ Merdas, Saifi; Mostephaoui, Tewfik; Belhamra, Mohamed (2017-07-01). "Reforestation in Algeria: History, current practice and future perspectives". Reforesta (3): 116. doi:10.21750/refor.3.10.34. ISSN 2466-4367.

- ↑ "Government approves creation of body in charge of reviving Green Dam". Algeria Press Service. 1 July 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

External links

The Green Dam in Algeria as a Tool to combat desertification

Monitoring the Spatiotemporal Evolution of the Green Dam in Djelfa Province, Algeria