| Ajax the Great | |

|---|---|

Prince of Salamis | |

| |

| Abode | Phthia |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | Telamon and Periboea |

| Siblings | Teucer, Trambelus, Telamon |

| Consort | Tecmessa |

| Offspring | Eurysaces, Philaeus |

| Trojan War |

|---|

|

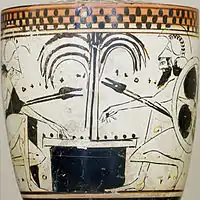

Ajax (/ˈeɪdʒæks/) or Aias (/ˈaɪ.əs/; Ancient Greek: Αἴας, romanized: Aíās [aí̯.aːs], gen. Αἴαντος Aíantos; archaic ΑΣϜΑϺ [aí̯.waːs])[lower-alpha 1] is a Greek mythological hero, the son of King Telamon and Periboea,[1] and the half-brother of Teucer.[2] He plays an important role in the Trojan War, and is portrayed as a towering figure and a warrior of great courage in Homer's Iliad and in the Epic Cycle, a series of epic poems about the Trojan War, being second only to Achilles among Greek heroes of the war.[3] He is also referred to as "Telamonian Ajax" (Αἴας ὁ Τελαμώνιος, in Etruscan recorded as Aivas Tlamunus), "Greater Ajax", or "Ajax the Great", which distinguishes him from Ajax, son of Oileus, also known as Ajax the Lesser.

Family

Ajax is the son of Telamon, who was the son of Aeacus and grandson of Zeus, and his first wife Periboea. By Telamon he is also the elder half-brother of Teucer. Through his uncle Peleus (Telamon's brother), he is the cousin of Achilles.

The etymology of his given name is uncertain. By folk etymology his name was said to come from the root of aiazō αἰάζω "to lament", translating to "one who laments; mourner". Hesiod provided a different folk etymology in a story in his "The Great Eoiae", where Ajax receives his name when Heracles prays to Zeus that a son might be born to Telemon and Eriboea: Zeus sends an eagle (aetos αετός) as a sign, and Heracles then bids the parents call their son Ajax after the eagle.[4]

Many illustrious Athenians, including Cimon, Miltiades, Alcibiades and the historian Thucydides, traced their descent from Ajax. On an Etruscan tomb dedicated to Racvi Satlnei in Bologna (5th century BC) there is an inscription that says aivastelmunsl, which means "[family] of Telamonian Ajax".[5]

Mythology

Description

In the account of Dares the Phrygian, Ajax was illustrated as ". . .powerful. His voice was clear, his hair black and curly. He was perfectly single-minded and unrelenting in the onslaught of battle."[6] Meanwhile, In Homer's Iliad he is described as of great stature, colossal frame, and strongest of all the Achaeans. Known as the "bulwark of the Achaeans",[7] he was trained by the centaur Chiron (who had trained Ajax's father Telamon and Achilles' father Peleus and later died of an accidental wound inflicted by Heracles, whom he was training at the same time as Achilles). He was described as fearless, strong, and powerful but also with a very high level of combat intelligence. Ajax commands his army wielding a huge shield made of seven cowhides with a layer of bronze. Most notably, Ajax is not wounded in any of the battles described in the Iliad, and he is the only principal character on either side who does not receive substantial assistance from any of the gods (except for Agamemnon) who take part in the battles, although, in book 13, Poseidon strikes Ajax with his staff, renewing his strength. Unlike Diomedes, Agamemnon, and Achilles, Ajax appears as a mainly defensive warrior, instrumental in the defense of the Greek camp and ships and that of Patroclus' body. When the Trojans are on the offensive, he is often seen covering the retreat of the Achaeans. Significantly, while one of the deadliest heroes in the whole poem, Ajax has no aristeia depicting him on the offensive.

Trojan War

In the Iliad, Ajax is notable for his abundant strength and courage, seen particularly in two fights with Hector. In Book 7, Ajax is chosen by lot to meet Hector in a duel which lasts most of a whole day. Ajax at first gets the better of the encounter, wounding Hector with his spear and knocking him down with a large stone,[8] but Hector battles on until the heralds, acting at the direction of Zeus, call a draw, with the two combatants exchanging gifts, Ajax giving Hector a purple sash and Hector giving Ajax his sharp sword.

The second fight between Ajax and Hector occurs when the latter breaks into the Mycenaean camp, and battles with the Greeks among the ships. In Book 14, Ajax throws a giant rock at Hector which almost kills him.[9] In Book 15, Hector is restored to his strength by Apollo and returns to attack the ships. Ajax, wielding an enormous spear as a weapon and leaping from ship to ship, holds off the Trojan armies virtually single-handedly. In Book 16, Hector and Ajax duel once again. Hector then disarms Ajax (although Ajax is not hurt) and Ajax is forced to retreat, seeing that Zeus is clearly favoring Hector. Hector and the Trojans succeed in burning one Greek ship, the culmination of an assault that almost finishes the war. Ajax is responsible for the death of many Trojan lords, including Phorcys.

Ajax often fought in tandem with his brother Teucer, known for his skill with the bow. Ajax would wield his magnificent shield, as Teucer stood behind picking off enemy Trojans.

Achilles was absent during these encounters because of his feud with Agamemnon. In Book 9, Agamemnon and the other Mycenaean chiefs send Ajax, Odysseus and Phoenix to the tent of Achilles in an attempt to reconcile with the great warrior and induce him to return to the fight. Although Ajax speaks earnestly and is well received, he does not succeed in convincing Achilles.

When Patroclus is killed, Hector tries to steal his body. Ajax, assisted by Menelaus, succeeds in fighting off the Trojans and taking the body back with his chariot; however, the Trojans have already stripped Patroclus of Achilles' armor. Ajax's prayer to Zeus to remove the fog that has descended on the battle to allow them to fight or die in the light of day has become proverbial. According to Hyginus, in total, Ajax killed 28 people at Troy.[10]

Death

.jpg.webp)

As the Iliad comes to a close, Ajax and the majority of other Greek warriors are alive and well. When Achilles dies, killed by Paris (with help from Apollo), Ajax and Odysseus are the heroes who fight against the Trojans to get the body and bury it with his companion, Patroclus.[11] Ajax, with his great shield and spear, manages to recover the body and carry it to the ships, while Odysseus fights off the Trojans.[12] After the burial, each claims Achilles' magical armor, which had been forged on Mount Olympus by the smith-god Hephaestus, for himself as recognition for his heroic efforts. A competition is held to determine who deserves the armor. Ajax argues that because of his strength and the fighting he has done for the Greeks, including saving the ships from Hector, and driving him off with a massive rock, he deserves the armor.[13] However, Odysseus proves to be more eloquent, and with the aid of Athena, the council gives him the armor. Ajax, distraught by this result and "conquered by his own grief", plunges his sword into his own chest, killing himself.[14] In the Little Iliad, Ajax goes mad with rage at Odysseus' victory and slaughters the cattle of the Greeks. After returning to his senses, he kills himself out of shame.[15] The Belvedere Torso, a marble torso now in the Vatican Museums, is considered to depict Ajax "in the act of contemplating his suicide".[16]

In Sophocles' play Ajax, a famous retelling of Ajax's demise, after the armor is awarded to Odysseus, Ajax feels so insulted that he wants to kill Agamemnon and Menelaus. Athena intervenes and clouds his mind and vision, and he goes to a flock of sheep and slaughters them, imagining they are the Achaean leaders, including Odysseus and Agamemnon. When he comes to his senses, covered in blood, he realizes that what he has done has diminished his honor, and decides that he prefers to kill himself rather than live in shame. He does so with the same sword which Hector gave him when they exchanged presents.[17] From his blood sprang a red flower, as at the death of Hyacinthus, which bore on its leaves the initial letters of his name Ai, also expressive of lament.[18] His ashes were deposited in a golden urn on the Rhoetean promontory at the entrance of the Hellespont.[19]

Ajax's half-brother Teucer stood trial before his father for not bringing Ajax's body or famous weapons back. Teucer was acquitted for responsibility but found guilty of negligence. He was disowned by his father and was not allowed to return to his home, the island of Salamis off the coast of Athens.

Homer is somewhat vague about the precise manner of Ajax's death but does ascribe it to his loss in the dispute over Achilles' armor; when Odysseus visits Hades, he begs the soul of Ajax to speak to him, but Ajax, still resentful over the old quarrel, refuses and descends silently back into Erebus.

Like Achilles, he is represented (although not by Homer) as living after his death on the island of Leuke at the mouth of the Danube.[20] Ajax, who in the post-Homeric legend is described as the grandson of Aeacus and the great-grandson of Zeus, was the tutelary hero of the island of Salamis, where he had a temple and an image, and where a festival called Aianteia was celebrated in his honour.[21] At this festival a couch was set up, on which the panoply of the hero was placed, a practice which recalls the Roman Lectisternium. The identification of Ajax with the family of Aeacus was chiefly a matter which concerned the Athenians, after Salamis had come into their possession, on which occasion Solon is said to have inserted a line in the Iliad (2.557–558),[22] for the purpose of supporting the Athenian claim to the island. Ajax then became an Attic hero; he was worshipped at Athens, where he had a statue in the market-place, and the tribe Aiantis was named after him.[19] Pausanias also relates that a gigantic skeleton, its kneecap 5 inches (13 cm) in diameter, appeared on the beach near Sigeion, on the Trojan coast; these bones were identified as those of Ajax.

Gallery

The suicide of Ajax. Etrurian red-figured calyx-krater, c. 400–350 BC.

The suicide of Ajax. Etrurian red-figured calyx-krater, c. 400–350 BC._Flaxman_Ilias_1795%252C_Zeichnung_1793%252C_186_x_283_mm.jpg.webp) Ajax battling Hector, engraving by John Flaxman, 1795

Ajax battling Hector, engraving by John Flaxman, 1795

A kylix with a depiction of the suicide of Ajax.

A kylix with a depiction of the suicide of Ajax.

Palace

In 2001, Yannos Lolos began excavating a Mycenaean palace near the village of Kanakia on the island of Salamis which he theorized to be the home of the mythological Aiacid dynasty. The multi-story structure covers 750 m2 (8,100 sq ft) and had perhaps 30 rooms. The palace appears to have been abandoned at the height of the Mycenaean civilization, roughly the same time the Trojan War may have occurred.[23][24]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Inscription on the so-called Eurytios Krater, a Corinthian black-figured column-krater dated c. 600 BC, using the Corinthian iota shaped like Σ.

Notes

- ↑ Tzetzes, John (2015). Allegories of the Iliad. Translated by Goldwyn, Adam; Kokkini, Dimitra. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England: Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library. pp. 41, Prologue 526. ISBN 978-0-674-96785-4.

- ↑ "Salamis The Island" Archived 2009-02-22 at the Wayback Machine Salamis The Island – Salamina Municipality – Greek Island

- ↑ Mike Dixon-Kennedy (1998). Encyclopedia of Greco-Roman Mythology. ABC-CLIO. p. 20. ISBN 1-57607-094-8.

- ↑ Most, Glenn Warren (2007). Hesiod, The Shield. Catalogue of Women. Other fragments (2018 revised ed.). Loeb Classical Library. p. 295, fragment 188. ISBN 978-0-674-99721-9.

- ↑ Papachristos, Maria. Miti e Leggende. Volume 5 of Miti e Leggende dell'antica Grecia. Edizioni R.E.I. (2015). ISBN 9782372971621

- ↑ Dares Phrygius, History of the Fall of Troy 13

- ↑ Homer, Iliad 6.5.

- ↑ Iliad, 7.268–272.

- ↑ Iliad, 14.408–417.

- ↑ Hyginus, Fabulae 114.

- ↑ Homer, Odyssey.

- ↑ Arctinus Miletus, "Aethiopis"

- ↑ Ovid, Metamorphoses, translated by Rolfe Humphries (Indianapolis: Indiana University, 1955), Book XIII, pp. 305–309

- ↑ Metamorphoses, trans. Humphries, p. 318

- ↑ Lesches of Mitylene, "The Little Iliad (Ilias Mikra)"

- ↑ "The Belvedere Torso; Cat. 1192". Vatican Museums. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- ↑ Iliad, 7.303

- ↑ Pausanias 1.35.4

- 1 2 One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ajax". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 452.

- ↑ Pausanias, Description of Greece iii. 19. § 13

- ↑ Pausanias 1.35

- ↑ Homer, Iliad 2.557–258.

- ↑ Carr, John (2006-03-28). "Palace of Homers hero rises out of the myths". The Times. London. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ↑ Paphitis, Nicohlas (30 March 2006). "Archeologist links Palace to Legendary Ajax". NBC News. Athens. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

References

- Homer. Iliad, 7.181–312.

- Homer, Odyssey 11.543–67.

- Bibliotheca. Epitome III, 11-V, 7.

- Graves, Robert, The Greek Myths, Harmondsworth, London, England, Penguin Books, 1960. ISBN 978-0143106715

- Graves, Robert, The Greek Myths: The Complete and Definitive Edition. Penguin Books Limited. 2017. ISBN 978-0-241-98338-6

- Ovid. Metamorphoses 12.620–13.398.

- Friedrich Schiller, Das Siegerfest.

- Pindar's Nemeans, 7, 8; Isthmian 4

- Tzetzes, John, Allegories of the Iliad translated by Goldwyn, Adam J. and Kokkini, Dimitra. Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library, Harvard University Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0-674-96785-4

External links

- A translation of the debate and Ajax's death. http://classics.mit.edu/Ovid/metam.13.thirteenth.html

- Paphitis, Nicholas (2006-03-30). "Archaeologist links palace to legendary Ajax". NBC News. Retrieved 2006-03-31.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)