.jpg.webp)

Fresco (pl. frescos or frescoes) is a technique of mural painting executed upon freshly laid ("wet") lime plaster. Water is used as the vehicle for the dry-powder pigment to merge with the plaster, and with the setting of the plaster, the painting becomes an integral part of the wall. The word fresco (Italian: affresco) is derived from the Italian adjective fresco meaning "fresh", and may thus be contrasted with fresco-secco or secco mural painting techniques, which are applied to dried plaster, to supplement painting in fresco. The fresco technique has been employed since antiquity and is closely associated with Italian Renaissance painting.[1][2]

The word fresco is commonly and inaccurately used in English to refer to any wall painting regardless of the plaster technology or binding medium. This, in part, contributes to a misconception that the most geographically and temporally common wall painting technology was the painting into wet lime plaster. Even in apparently Buon fresco technology, the use of supplementary organic materials was widespread, if underrecognized.[3]

Technology

Buon fresco pigment is mixed with room temperature water and is used on a thin layer of wet, fresh plaster, called the intonaco (after the Italian word for plaster). Because of the chemical makeup of the plaster, a binder is not required, as the pigment mixed solely with the water will sink into the intonaco, which itself becomes the medium holding the pigment. The pigment is absorbed by the wet plaster; after a number of hours, the plaster dries in reaction to air: it is this chemical reaction which fixes the pigment particles in the plaster. The chemical processes are as follows:[4]

- calcination of limestone in a lime kiln: CaCO3 → CaO + CO2

- slaking of quicklime: CaO + H2O → Ca(OH)2

- setting of the lime plaster: Ca(OH)2 + CO2 → CaCO3 + H2O

In painting buon fresco, a rough underlayer called the arriccio is added to the whole area to be painted and allowed to dry for some days. Many artists sketched their compositions on this underlayer, which would never be seen, in a red pigment called sinopia, a name also used to refer to these under-paintings. Later,new techniques for transferring paper drawings to the wall were developed. The main lines of a drawing made on paper were pricked over with a point, the paper held against the wall, and a bag of soot (spolvero) banged on them to produce black dots along the lines. If the painting was to be done over an existing fresco, the surface would be roughened to provide better adhesion. On the day of painting, the intonaco, a thinner, smooth layer of fine plaster was added to the amount of wall that was expected to be completed that day, sometimes matching the contours of the figures or the landscape, but more often just starting from the top of the composition. This area is called the giornata ("day's work"), and the different day stages can usually be seen in a large fresco, by a faint seam that separates one from the next.

Buon frescoes are difficult to create because of the deadline associated with the drying plaster. Generally, a layer of plaster will require ten to twelve hours to dry; ideally, an artist would begin to paint after one hour and continue until two hours before the drying time—giving seven to nine hours' working time. Once a giornata is dried, no more buon fresco can be done, and the unpainted intonaco must be removed with a tool before starting again the next day. If mistakes have been made, it may also be necessary to remove the whole intonaco for that area—or to change them later, a secco. An indispensable component of this process is the carbonatation of the lime, which fixes the colour in the plaster ensuring durability of the fresco for future generations.[5]

A technique used in the popular frescoes of Michelangelo and Raphael was to scrape indentations into certain areas of the plaster while still wet to increase the illusion of depth and to accent certain areas over others. The eyes of the people of the School of Athens are sunken-in using this technique which causes the eyes to seem deeper and more pensive. Michelangelo used this technique as part of his trademark 'outlining' of his central figures within his frescoes.

In a wall-sized fresco, there may be ten to twenty or even more giornate, or separate areas of plaster. After five centuries, the giornate, which were originally nearly invisible, have sometimes become visible, and in many large-scale frescoes, these divisions may be seen from the ground. Additionally, the border between giornate was often covered by an a secco painting, which has since fallen off.

One of the first painters in the post-classical period to use this technique was the Isaac Master (or Master of the Isaac fresco, and thus a name used to refer to the unknown master of a particular painting) in the Upper Basilica of Saint Francis in Assisi. A person who creates fresco is called a frescoist.

Other types of wall painting

A secco or fresco-secco painting is done on dry plaster (secco meaning "dry" in Italian). The pigments thus require a binding medium, such as egg (tempera), glue or oil to attach the pigment to the wall. It is important to distinguish between a secco work done on top of buon fresco, which according to most authorities was in fact standard from the Middle Ages onwards, and work done entirely a secco on a blank wall. Generally, buon fresco works are more durable than any a secco work added on top of them, because a secco work lasts better with a roughened plaster surface, whilst true fresco should have a smooth one. The additional a secco work would be done to make changes, and sometimes to add small details, but also because not all colours can be achieved in true fresco, because only some pigments work chemically in the very alkaline environment of fresh lime-based plaster. Blue was a particular problem, and skies and blue robes were often added a secco, because neither azurite blue nor lapis lazuli, the only two blue pigments then available, works well in wet fresco.[6]

It has also become increasingly clear, thanks to modern analytical techniques, that even in the early Italian Renaissance painters quite frequently employed a secco techniques so as to allow the use of a broader range of pigments. In most early examples this work has now entirely vanished, but a whole painting done a secco on a surface roughened to give a key for the paint may survive very well, although damp is more threatening to it than to buon fresco.

A third type called a mezzo-fresco is painted on nearly dry intonaco—firm enough not to take a thumb-print, says the sixteenth-century author Ignazio Pozzo—so that the pigment only penetrates slightly into the plaster. By the end of the sixteenth century this had largely displaced buon fresco, and was used by painters such as Gianbattista Tiepolo or Michelangelo. This technique had, in reduced form, the advantages of a secco work.

The three key advantages of work done entirely a secco were that it was quicker, mistakes could be corrected, and the colours varied less from when applied to when fully dry—in wet fresco there was a considerable change.

For wholly a secco work, the intonaco is laid with a rougher finish, allowed to dry completely and then usually given a key by rubbing with sand. The painter then proceeds much as he or she would on a canvas or wood panel.

History

.jpg.webp)

Egypt and Ancient Near East

The first known Egyptian fresco was found in Tomb 100 at Hierakonpolis, and dated to c. 3500–3200 BC. Several of the themes and designs visible in the fresco are otherwise known from other Naqada II objects, such as the Gebel el-Arak Knife. It shows the scene of a "Master of Animals", a man fighting against two lions, individual fighting scenes, and Egyptian and foreign boats.[7][8][9][10][11] Ancient Egyptians painted many tombs and houses, but those wall paintings are not frescoes.[12]

An old fresco from Mesopotamia is the Investiture of Zimri-Lim (modern Syria), dating from the early 18th century BC.

Aegean civilizations

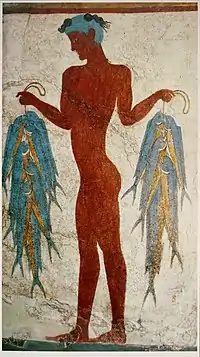

The oldest frescoes done in the buon fresco method date from the first half of the second millennium BCE during the Bronze Age and are to be found among Aegean civilizations, more precisely Minoan art from the island of Crete and other islands of the Aegean Sea. The most famous of these, the Bull-Leaping Fresco, depicts a sacred ceremony in which individuals jump over the backs of large bulls. The oldest surviving Minoan frescoes are found on the island of Santorini (classically known as Thera), dated to the Neo-Palatial period (c. 1640–1600 BC).

While some similar frescoes have been found in other locations around the Mediterranean basin, particularly in Egypt and Morocco, their origins are subject to speculation. Some art historians believe that fresco artists from Crete may have been sent to various locations as part of a trade exchange, a possibility which raises to the fore the importance of this art form within the society of the times. The most common form of fresco was Egyptian wall paintings in tombs, usually using the a secco technique.

Classical antiquity

Frescoes were also painted in ancient Greece, but few of these works have survived. In southern Italy, at Paestum, which was a Greek colony of the Magna Graecia, a tomb containing frescoes dating back to 470 BC, the so-called Tomb of the Diver, was discovered in June 1968. These frescoes depict scenes of the life and society of ancient Greece, and constitute valuable historical testimonials. One shows a group of men reclining at a symposium, while another shows a young man diving into the sea. Etruscan frescoes, dating from the 4th century BC, have been found in the Tomb of Orcus near Veii, Italy.

The richly decorated Thracian frescoes of the Tomb of Kazanlak are dating back to 4th century BC, making it a UNESCO protected World Heritage Site.

Roman wall paintings, such as those at the magnificent Villa dei Misteri (1st century BC) in the ruins of Pompeii, and others at Herculaneum, were completed in buon fresco.

Roman (Christian) frescoes from the 1st to 2nd centuries AD were found in catacombs beneath Rome, and Byzantine icons were also found in Cyprus, Crete, Ephesus, Cappadocia, and Antioch. Roman frescoes were done by the artist painting the artwork on the still damp plaster of the wall, so that the painting is part of the wall, actually colored plaster.

Also a historical collection of Ancient Christian frescoes can be found in the Churches of Göreme.

India

Thanks to large number of ancient rock-cut cave temples, valuable ancient and early medieval frescoes have been preserved in more than 20 locations of India.[13] The frescoes on the ceilings and walls of the Ajanta Caves were painted between c. 200 BC and 600 and are the oldest known frescoes in India. They depict the Jataka tales that are stories of the Buddha's life in former existences as Bodhisattva. The narrative episodes are depicted one after another although not in a linear order. Their identification has been a core area of research on the subject since the time of the site's rediscovery in 1819. Other locations with valuable preserved ancient and early medieval frescoes include Bagh Caves, Ellora Caves, Sittanavasal, Armamalai Cave, Badami Cave Temples and other locations. Frescoes have been made in several techniques, including tempera technique.

The later Chola paintings were discovered in 1931 within the circumambulatory passage of the Brihadisvara Temple in India and are the first Chola specimens discovered.

Researchers have discovered the technique used in these frescos. A smooth batter of limestone mixture was applied over the stones, which took two to three days to set. Within that short span, such large paintings were painted with natural organic pigments.

During the Nayak period, the Chola paintings were painted over. The Chola frescos lying underneath have an ardent spirit of saivism expressed in them. They probably synchronised with the completion of the temple by Rajaraja Cholan the Great.

The frescoes in Dogra/ Pahari style paintings exist in their unique form at Sheesh Mahal of Ramnagar (105 km from Jammu and 35 km west of Udhampur). Scenes from epics of Mahabharat and Ramayan along with portraits of local lords form the subject matter of these wall paintings. Rang Mahal of Chamba (Himachal Pradesh) is another site of historic Dogri fresco with wall paintings depicting scenes of Draupti Cheer Haran, and Radha- Krishna Leela. This can be seen preserved at National Museum at New Delhi in a chamber called Chamba Rang Mahal.

During the Mughal Era, frescos were used for making interior design on walls and inside the ceilings of domes.[14]

Sri Lanka

The Sigiriya Frescoes are found in Sigiriya in Sri Lanka. Painted during the reign of King Kashyapa I (ruled 477 – 495 AD). The generally accepted view is that they are portrayals of women of the royal court of the king depicted as celestial nymphs showering flowers upon the humans below. They bear some resemblance to the Gupta style of painting found in the Ajanta Caves in India. They are, however, far more enlivened and colorful and uniquely Sri Lankan in character. They are the only surviving secular art from antiquity found in Sri Lanka today.

The painting technique used on the Sigiriya paintings is "fresco lustro". It varies slightly from the pure fresco technique in that it also contains a mild binding agent or glue. This gives the painting added durability, as clearly demonstrated by the fact that they have survived, exposed to the elements, for over 1,500 years.[15]

Located in a small sheltered depression a hundred meters above ground only 19 survive today. Ancient references, however, refer to the existence of as many as five hundred of these frescoes.

Middle Ages

The late Medieval period and the Renaissance saw the most prominent use of fresco, particularly in Italy, where most churches and many government buildings still feature fresco decoration. This change coincided with the reevaluation of murals in the liturgy.[16] Romanesque churches in Catalonia were richly painted in 12th and 13th century, with both decorative and educational—for the illiterate faithfuls—roles, as can be seen in the MNAC in Barcelona, where is kept a large collection of Catalan romanesque art.[17] In Denmark too, church wall paintings or kalkmalerier were widely used in the Middle Ages (first Romanesque, then Gothic) and can be seen in some 600 Danish churches as well as in churches in the south of Sweden, which was Danish at the time.[18]

One of the rare examples of Islamic fresco painting can be seen in Qasr Amra, the desert palace of the Umayyads in the 8th century Magotez.

Early modern Europe

Fresco painting continued into the Baroque in southern Europe, for churches and especially palaces. Gianbattista Tiepolo was arguably the last major exponent of this tradition, with huge schemes for palaces in Madrid and Würzburg in Germany.

Northern Romania (historical region of Moldavia) boasts about a dozen painted monasteries, completely covered with frescos inside and out, that date from the last quarter of the 15th century to the second quarter of the 16th century. The most remarkable are the monastic foundations at Voroneţ (1487), Arbore (1503), Humor (1530), and Moldoviţa (1532). Suceviţa, dating from 1600, represents a late return to the style developed some 70 years earlier. The tradition of painted churches continued into the 19th century in other parts of Romania, although never to the same extent.[19]

Henri Clément Serveau produced several frescos including a three by six meter painting for the Lycée de Meaux, where he was once a student. He directed the École de fresques at l'École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts, and decorated the Pavillon du Tourisme at the 1937 Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne (Paris), Pavillon de la Ville de Paris; now at Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris.[20] In 1954 he realized a fresco for the Cité Ouvrière du Laboratoire Débat, Garches.[21] He also executed mural decorations for the Plan des anciennes enceintes de Paris in the Musée Carnavalet.[22]

The Foujita chapel in Reims completed in 1966, is an example of modern frescos, the interior being painted with religious scenes by the School of Paris painter Tsuguharu Foujita. In 1996, it was designated an historic monument by the French government.

Mexican muralism

José Clemente Orozco, Fernando Leal, David Siqueiros and Diego Rivera the famous Mexican artists, renewed the art of fresco painting in the 20th century. Orozco, Siqueiros, Rivera and his wife Frida Kahlo contributed more to the history of Mexican fine arts and to the reputation of Mexican art in general than anybody else. Channeling pre-Columbian Mexican artworks including the true frescoes at Teotihuacan, Orozco, Siqueiros, River and Fernando Leal established the art movement known as Mexican Muralism.[23]

Contemporary

There have been comparatively few frescoes created since the 1960s but there are some significant exceptions.

The American artist, Brice Marden's monochrome works first shown in 1966 at Bykert Gallery, New York were inspired by frescos and "watching masons plastering stucco walls."[24] While Marden employed the imagistic effects of fresco, David Novros was developing a 50-year practice around the technique. David Novros is an American painter and a muralist of geometric abstraction. In 1968 Donald Judd commissioned Novros to create a work at 101 Spring Street, New York, NY soon after he had purchased the building.[25] Novros used medieval techniques to create the mural by "first preparing a full-scale cartoon, which he transferred to the wet plaster using the traditional pouncing technique," the act of passing powdered pigment onto the plaster through tiny perforations in a cartoon.[26] The surface unity of the fresco was important to Novros in that the pigment he used bonded with the drying plaster, becoming part of the wall rather than a surface coating. This site-specific work was Novros's first true fresco, which was restored by the artist in 2013.

The American painter, James Hyde first presented frescoes in New York at the Esther Rand Gallery, Thompkins Square Park in 1985. At that time Hyde was using true fresco technique on small panels made of cast concrete arranged on the wall. Throughout the next decade Hyde experimented with multiple rigid supports for the fresco plaster including composite board and plate glass. In 1991 at John Good Gallery in New York City, Hyde debuted true fresco applied on an enormous block of Styrofoam. Holland Cotter of the New York Times described the work as "objectifying some of the individual elements that have made modern paintings paintings."[27] While Hyde's work "ranges from paintings on photographic prints to large-scale installations, photography, and abstract furniture design" his frescoes on Styrofoam have been a significant form of his work since the 1980s.[28]

The frescoes have been shown throughout Europe and the United States. In ArtForum David Pagel wrote, "like ruins from some future archaeological dig, Hyde's nonrepresentational frescoes on large chunks of Styrofoam give suggestive shape to the fleeting landscape of the present."[29] Over its long history, practitioners of frescoes always took a careful methodological approach. Hyde's frescoes are done improvisationally. The contemporary disposability of the Styrofoam structure contrast the permanence of the classical fresco technique. In 1993, Hyde mounted four automobile sized frescoes on Styrofoam suspended from a brick wall. Progressive Insurance commissioned this site-specific work for the monumental 80- foot atrium in their headquarters in Cleveland, Ohio.[30]

Selected examples of frescoes

_de_Jos%C3%A9_Clemente_Orozco_en_Pomona_College.jpg.webp)

Ancient and Early Medieval

Italian Late Medieval-Quattrocento

- Panels (including Giotto(?), Lorenzetti, Martini and others) in upper and lower Basilica of San Francesco d'Assisi

- Giotto, Cappella degli Scrovegni (Arena Chapel), Padua

- Camposanto, Pisa

- Masaccio, Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence

- Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Palazzo Pubblico, Siena

- Piero della Francesca, Chiesa di San Francesco, Arezzo

- Ghirlandaio, Cappella Tornabuoni, Santa Maria Novella, Florence

- The Last Supper, Leonardo da Vinci, Milan (technically a tempera on plaster and stone, not a true fresco[31])

- Sistine Chapel Wall series: Botticelli, Perugino, Rossellini, Signorelli, and Ghirlandaio

- Luca Signorelli, Chapel of San Brizio, Duomo, Orvieto

Italian High Renaissance

- Michelangelo, Sistine Chapel ceiling

- Raphael, Raphael Rooms

- Raphael, Villa Farnesina

- Giulio Romano's Palazzo del Tè, Mantua

- Mantegna, Camera degli Sposi, Palazzo Ducale, Mantua

- The dome of the Florence Cathedral

- The Loves of the Gods, Annibale Carracci, Palazzo Farnese, Rome

- Allegory of Divine Providence and Barberini Power, Pietro da Cortona, Palazzo Barberini

- Ceilings, Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, (New Residenz) Würzburg, (Royal Palace) Madrid, (Villa Pisani) Stra, and others; Wall scenes (Villa Valmarana and Palazzo Labia)

- Nave ceiling, Andrea Pozzo, Sant'Ignazio, Rome

Bulgaria

Serbian Medieval

Czech Republic

Mexico

- Fresco Cycle of The Miracles of the Virgin of Guadalupe by Fernando Leal, at Basilica of Guadalupe, Mexico City

- Fresco Cycle of Bolivar's Epic by Fernando Leal, at Colegio de San Ildefonso, Mexico City

Note: Fresco cycle, a series of frescos done about a particular subject

Note: Fresco cycle, a series of frescos done about a particular subject

Colombia

- Santiago Martinez Delgado frescoed a mural in the Colombian Congress Building, and also in the Colombian National Building.

France

United States

- Prometheus in Pomona College's Frary Dining Hall. Painted in 1930 by José Clemente Orozco, it is the first example of a modern, Mexican fresco mural in the U.S.[32]

- St. Ann Arts and Cultural Center in Woonsocket, RI. Home of the largest collection of fresco paintings in North America.

Conservation of frescoes

The climate and environment of Venice has proved to be a problem for frescoes and other works of art in the city for centuries. The city is built on a lagoon in northern Italy. The humidity and the rise of water over the centuries have created a phenomenon known as rising damp. As the lagoon water rises and seeps into the foundation of a building, the water is absorbed and rises up through the walls often causing damage to frescoes. Venetians have become quite adept in the conservation methods of frescoes. The mold aspergillus versicolor can grow after flooding, to consume nutrients from frescoes.[33][34]

The following is the process that was used when rescuing frescoes in La Fenice, a Venetian opera house, but the same process can be used for similarly damaged frescoes. First, a protection and support bandage of cotton gauze and polyvinyl alcohol is applied. Difficult sections are removed with soft brushes and localized vacuuming. The other areas that are easier to remove (because they had been damaged by less water) are removed with a paper pulp compress saturated with bicarbonate of ammonia solutions and removed with deionized water. These sections are strengthened and reattached then cleansed with base exchange resin compresses and the wall and pictorial layer were strengthened with barium hydrate. The cracks and detachments are stopped with lime putty and injected with an epoxy resin loaded with micronized silica.[35]

Gallery

- Frescos

Chola Fresco of Dancing girls. Brihadisvara Temple c. 1100

Chola Fresco of Dancing girls. Brihadisvara Temple c. 1100

On the left, Anthony the Great, crucifixion with the Virgin and Saint John, on the right, the Archangel Michael. Abbey church of Saint-Antoine l'Abbaye, France

On the left, Anthony the Great, crucifixion with the Virgin and Saint John, on the right, the Archangel Michael. Abbey church of Saint-Antoine l'Abbaye, France "Good-natured giant Saint Christopher carrying the child Jesus." Abbey church of Saint-Antoine l'Abbaye, France

"Good-natured giant Saint Christopher carrying the child Jesus." Abbey church of Saint-Antoine l'Abbaye, France Chapel of the Holy Cross in Wawel Cathedral in Kraków

Chapel of the Holy Cross in Wawel Cathedral in Kraków

Byzantine and Bulgarian, Dome of the Church of St. George, Sofia

Byzantine and Bulgarian, Dome of the Church of St. George, Sofia

See also

References

- ↑ Mora, Paolo; Mora, Laura; Philippot, Paul (1984). Conservation of Wall Paintings. Butterworths. pp. 34–54. ISBN 0-408-10812-6.

- ↑ Ward, Gerald W. R., ed. (2008). The GroveEncyclopedia of Materials and Techniques in Art. Oxford University Press. pp. 223–5. ISBN 978-0-19-531391-8.

- ↑ Piqué, Francesca (2015). Organic materials in wall paintings : project report. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. ISBN 978-1-937433-29-1. OCLC 944038739.

- ↑ Mora, Paolo; Mora, Laura; Philippot, Paul (1984). Conservation of Wall Paintings. Butterworths. pp. 47–54. ISBN 0-408-10812-6.

- ↑ How is a fresco made? - Fresco Blog Archived 18 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine by Italian Fresco Blog.

- ↑ All this section - Ugo Procacci, in Frescoes from Florence, pp. 15–25 1969, Arts Council, London.

- ↑ Case, Humphrey; Payne, Joan Crowfoot (1962). "Tomb 100: The Decorated Tomb at Hierakonpolis". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 48: 17. doi:10.2307/3855778. ISSN 0307-5133. JSTOR 3855778.

- ↑ Shaw, Ian (2019). Ancient Egyptian Warfare: Tactics, Weaponry and Ideology of the Pharaohs. Open Road Media. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-5040-6059-2.

- ↑ Kemp, Barry J. (2007). Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilisation. Routledge. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-134-56389-0.

- ↑ Bestock, Laurel (2017). Violence and Power in Ancient Egypt: Image and Ideology before the New Kingdom. Routledge. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-134-85626-8.

- ↑ Hartwig, Melinda K. (2014). A Companion to Ancient Egyptian Art. John Wiley & Sons. p. 424. ISBN 978-1-118-32509-4.

- ↑ Nina M. Davies: Ancient Egyptian paintings, Vol. III, Chicago, 1963, p. xxxi online Archived 10 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Ancient and medieval Indian cave paintings - Internet encyclopedia Archived 24 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine by Wondermondo. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ↑ "Lahore Its History, Architectural Remains and Antiquities". 1892.

- ↑ Ponnamperuma, Senani (2013). Story of Sigiriya. Melbourne: Panique Pty Ltd. ISBN 9780987345110.

- ↑ Bokody, Peter (January 2014). "Péter Bokody, Mural Painting as a Medium: Technique, Representation and Liturgy, Image and Christianity: Visual Media in the Middle Ages, Pannonhalma Abbey, 2014, 136-151". Péter Bokody (Ed.). Image and Christianity: Visual Media in the Middle Ages. Exhibition Catalog. Pannonhalma: Pannonhalma Abbey, 2014.

- ↑ Español, Francesca; Yarza, Joaquín; fotografies de Ramon Manent, Pere Pascual i Rosina Ramírez (2007). El romànic català (in Catalan) (1. ed.). Barcelona: Angle Editorial. ISBN 9788496970090.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Kirsten Trampedach, "Introduction to Danish wall paintings - Conservation ethics and methods of treatment from the National Museum of Denmark" Archived 24 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ↑ Anca Vasiliu, "Monastères de Moldavie (XIVème-XVIème siècles)", Paris Mediterranée, 1998

- ↑ "Ministère de la Culture (France) - Médiathèque de l'architecture et du patrimoine, Exposition internationale des arts et techniques de 1937".

- ↑ Base Mérimée: Cité ouvrière du Laboratoire Débat, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- ↑ "Waterhouse & Dodd Fine Art 1850-2000". Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ↑ Sophie Friedman. "Mexican Muralism | Modern Latin America". Brown University Library.

- ↑ Brooklyn Rail Archived 5 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine "Brice Marden with Jeffrey Weiss", October 2006.

- ↑ Judd Foundation Archived 5 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine "Index of works- David Novros", 2013.

- ↑ Matthew L. Levy, "David Novro’s Painted Places", in David Novros, exh. Cat. (Bielefeld: Kerber, 2014),50.

- ↑ Holland Cotter,New York Times Archived 5 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine "Art in Review", March 1993.

- ↑ Guggenheim, John Simon Memorial Foundation Archived 5 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine Awarded Fellows, 2008.

- ↑ David Pagel, "James Hyde, Angles Gallery" Archived 5 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine Art Forum, December 1993.

- ↑ Progressive Insurance, "Installations- James Hyde" Archived 5 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine Progressive Insurance, 1993.

- ↑ "Restoration of the Last Supper 1498 - Leonardo da Vinci 1452-1519 - The Last Supper St. Apostle John Comparison". Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ↑ Scott, David W. (1957). "Orozco's Prometheus: Summation, Transition, Innovation". College Art Journal. 17 (1): 2–18. doi:10.2307/773653. ISSN 1543-6322. JSTOR 773653.

- ↑ Bennett JW (2010). "An Overview of the Genus Aspergillus" (PDF). Aspergillus: Molecular Biology and Genomics. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-53-0. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 April 2011.

- ↑ Orio Ciferri (March 1999). "Microbial Degradation of Paintings". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 65 (3): 879–885. Bibcode:1999ApEnM..65..879C. doi:10.1128/AEM.65.3.879-885.1999. PMC 91117. PMID 10049836.

- ↑ Ciacci, Leonardo., ed, La Fenice Reconstructed 1996–2003: a building site in the city, (Venezia: Marsilio, 2003),118.