Abusir el-Meleq (Ar. أبو صير الملق), also Abusir el-Melek - a town and archaeological site in Egypt, located in Beni Suef (Arabic: بني سويف, romanized: Baniswēf) is the capital city of the Beni Suef Governorate in Egypt an important agricultural trade centre on the west bank of the Nile river, the city is located 110 km (70 miles) south of Cairo.[1]

History

The archaeological site Abusir el-Meleq was occupied from at least 3250BCE until about 700CE and was of great religious importance because of its active cult to Osiris The necropolis of Abusir el-Meleq, north of the Fayum entrance, was discovered and excavated by the German archaeologist Otto Rubensohn in four campaigns between 1902 and 1905. On behalf of the Papyrussammlung of the Egyptian Museum of Berlin Rubensohn searched for papyri near the village and discovered prehistoric graves. Within a few months, the German Oriental Society organized an expedition led by the Egyptologist Georg Möller. Excavations took place in the summer of 1905 and in the fall of 1906. The excavations uncovered approximately 850 graves that have been identified as belonging to the Naqada II and Naqada III cultures. Later research showed that the site was a place of residence, cemeteries and temples for several thousand years. The oldest graves were of the Naqada, the later ones were used in Greek period, Roman and from the time of Arab rule. Despite the rich finds of burial objects, including even complete burial furnishings, these have so far remained largely unpublished. They include objects from the predynastic to the Islamic period of Egypt, with finds from the Third Intermediate Period up to the Greco-Roman period making up the main part. A total of more than 345 graves with well over 700 burials were uncovered. Of these finds, around 400 individual objects are in Berlin alone, and more than 200 objects were distributed to various collections in the then German Empire with the help of the German Orient Society. Many of those buried in Abusir el-Meleq were priests or singers of the god Herischef, who had his cult center in Herakleopolis Magna, about 20 km away. The burial of a girl Tadja who died young, an outstanding example of a complete grave inventory. Almost 60 individual objects were found in her grave alone. In addition to inner and outer coffins, these include finger rings, amulets, musical instruments, headrests, faience vessels and small female and male sculptures dating from the period of the 25-26th Dynasty. In Abusir el-Meleq there is evidence of several large tombs with up to 20 chambers for well over 50 burials, especially from the Greco-Roman period, which have been repeatedly occupied since the Late Period. The Roman-era cemetery of Abusir el-Meleq of the 1st and 2nd centuries AD are unusual burials and are found nowhere else in Egypt. Written sources show that by the third century BCE Abusir el-Meleq was at the center of a wider region that comprised the northern part of the Herakleopolites nome, and had close ties with the Fayum and the Memphite provinces involving cattle-breeding, the transport of wheat, bee-keeping and quarrying. In the early Roman Period, the site may have been its own district. Abusir el-Meleq's proximity to, and close ties with the Fayum led to substantial growth in its population during the first hundred years of Ptolemaic rule, presumably as a result of Greek immigration. Later, in the Roman Period, many veterans of the Roman military were not Egyptian but people from various cultural backgrounds who settled in the Fayum area after the completion of their service, some intermarrying with local populations. Individuals with Greek, Latin and Hebrew names are known to have lived at the site and several coffins found at the cemetery used Greek portrait images and adapted Greek statue types to suit ‘Egyptian’ burial practices. [2][3]

Study

2017 DNA study

A study published in 2017 by Schuenemann et al. extracted DNA from 151 Egyptian mummies, whose remains were recovered from Abusir el-Meleq in Middle Egypt. The samples are from the time periods: Late New Kingdom, Ptolemaic, and Roman. Complete mtDNA sequences from 90 samples as well as genome-wide data from three ancient Egyptian individuals were successfully obtained and were compared with other ancient and modern datasets. The study used 135 modern Egyptian samples. The ancient Egyptian individuals in their own dataset possessed highly similar mtDNA haplogroup profiles, and cluster together, supporting genetic continuity across the 1,300-year transect. Modern Egyptians shared this mtDNA haplogroup profile, but also carried 8% more African component. A wide range of mtDNA haplogroups were found including clades of J, U, H, HV, M, R0, R2, K, T, L, I, N, X and W. The three ancient Egyptian individuals were analysed for Y-DNA, two were assigned to West Asian haplogroup J and one to haplogroup E1b1b1 both are carried by modern Egyptians, and also common among Afroasiatic speakers in Northern Africa, Eastern Africa and the Middle East. The researchers cautioned that the examined ancient Egyptian specimens may not be representative of those of all ancient Egyptians since they were from a single archaeological site from the northern part of Egypt.[3] The analyses revealed higher affinities with Near Eastern and European populations compared to modern Egyptians, likely due to the 8% increase in the African component.[3] However, comparative data from a contemporary population under Roman rule in Anatolia, did not reveal a closer relationship to the ancient Egyptians from the Roman period.[3] "Genetic continuity between ancient and modern Egyptians cannot be ruled out despite this more recent sub-Saharan African influx, while continuity with modern Ethiopians is not supported".[3]

The absolute estimates of sub-Saharan African ancestry in these three ancient Egyptian individuals ranged from 6 to 15%, and the absolute estimates of sub-Saharan African ancestry in the 135 modern Egyptian samples ranged from 14 to 21%, which show an 8% increase in African component. The age of the ancient Egyptian samples suggests that this 8% increase in African component occurred predominantly within the last 2000 years.[3] The 135 modern Egyptian samples were: 100 from modern Egyptians taken from a study by Pagani et al., and 35 from el-Hayez Western Desert Oasis taken from a study by Kujanova et al.[3] The 35 samples from el-Hayez Western Desert Oasis, whose population is described by the Kujanova et al. study as a mixed, relatively isolated, demographically small but autochthonous population, were already known from that study to have a relatively high sub-Saharan African component,[4] which is more than 11% higher than the African component in the 100 modern Egyptian samples.[5]

Verena Schuenemann and the authors of this study suggest a high level of genetic interaction with the Near East since ancient times, probably going back to Prehistoric Egypt although the oldest mummies at the site were from the New Kingdom: "Our data seem to indicate close admixture and affinity at a much earlier date, which is unsurprising given the long and complex connections between Egypt and the Middle East. These connections date back to Prehistory and occurred at a variety of scales, including overland and maritime commerce, diplomacy, immigration, invasion and deportation"[3]

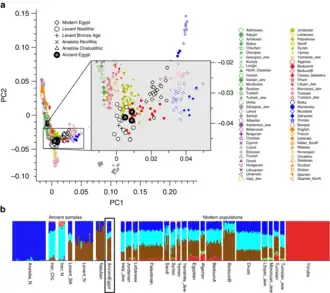

PCA and ADMIXTURE analysis of three ancient Egyptian samples and other modern and ancient populations.[3]

PCA and ADMIXTURE analysis of three ancient Egyptian samples and other modern and ancient populations.[3] PCA using only European samples based on the nuclear genome-wide data obtained on three ancient Egyptian samples.[3]

PCA using only European samples based on the nuclear genome-wide data obtained on three ancient Egyptian samples.[3] Complete results from the ADMIXTURE analysis using all samples in the merged data set, from the 2017 study by Schuenemann et al.[3]

Complete results from the ADMIXTURE analysis using all samples in the merged data set, from the 2017 study by Schuenemann et al.[3] FST values showing the genetic distances between 90 ancient Egyptians and modern populations. Blue values depict higher genetic distances, red values depict lower genetic distances between the ancient Egyptian population and modern populations in the respective area.[3]

FST values showing the genetic distances between 90 ancient Egyptians and modern populations. Blue values depict higher genetic distances, red values depict lower genetic distances between the ancient Egyptian population and modern populations in the respective area.[3]

Criticisms of the 2017 DNA study

Gourdine, Anselin and Keita criticised the methodology of the Scheunemann et al. study. They specifically criticised the claim that the increase in the sub-Saharan component in the modern Egyptian samples resulted from the trans-Saharan slave trade and argued that the sub-Saharan "genetic affinities" may be attributed to "early settlers" and "the relevant sub-Saharan genetic markers" do not correspond with the geography of known trade routes".[6]

In 2022, archaeologist Danielle Candelora claimed that there were several limitations with the 2017 Scheunemann et al. study such as “new (untested) sampling methods, small sample size and problematic comparative data”.[7] Candelora noted that the findings of Scheunemann et al. were based largely on the only three mummies from which genome-wide samples were recovered. [8]

In 2023, Christopher Ehret argued that the conclusions of the 2017 study were based on insufficiently small sample sizes, and that the authors had a biased interpretation of the genetic data.[9] Ehret also criticised the study for asserting that there was “no sub-Saharan” component in the Egyptian population. Ehret cited other genetic evidence which had identified the Horn of Africa as a source of a genetic marker “M35 /215” Y-chromosome lineage for a significant population component which moved north from that region into Egypt and the Levant.[10]

References

- ↑ "Abusir el Meleq Map". EurekAlert!. Retrieved 2023-07-15.

- ↑ Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection Otto Rubensohn in Ägypten - Vergessene Grabungen: Funde und Archivalien aus den Grabungen der Königlichen Museen zu Berlin (1901-1907/08)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Krause, Johannes; Schiffels, Stephan (30 May 2017). "Ancient Egyptian mummy genomes suggest an increase of Sub-Saharan African ancestry in post-Roman periods". Nature Communications. 8: 15694. Bibcode:2017NatCo...815694S. doi:10.1038/ncomms15694. PMC 5459999. PMID 28556824.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license. - ↑ Kujanová M, Pereira L, Fernandes V, Pereira JB, Cerný V (October 2009). "Near eastern neolithic genetic input in a small oasis of the Egyptian Western Desert". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 140 (2): 336–46. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21078. PMID 19425100.

- ↑ Pagani, Luca; Schiffels, Stephan; Gurdasani, Deepti; Danecek, Petr; Scally, Aylwyn; Chen, Yuan; Xue, Yali; Haber, Marc; Ekong, Rosemary; Oljira, Tamiru; Mekonnen, Ephrem (2015-06-04). "Tracing the route of modern humans out of Africa by using 225 human genome sequences from Ethiopians and Egyptians". American Journal of Human Genetics. 96 (6): 986–991. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.04.019. ISSN 1537-6605. PMC 4457944. PMID 26027499.

- ↑ Eltis, David; Bradley, Keith R.; Perry, Craig; Engerman, Stanley L.; Cartledge, Paul; Richardson, David (12 August 2021). The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 2, AD 500-AD 1420. Cambridge University Press. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-521-84067-5.

- ↑ Candelora, Danielle (31 August 2022). Candelora, Danielle; Ben-Marzouk, Nadia; Cooney, Kathyln (eds.). Ancient Egyptian society : challenging assumptions, exploring approaches. Abingdon, Oxon. pp. 101–111. ISBN 9780367434632.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Candelora, Danielle (31 August 2022). "10: The Egyptianization of Egypt and Egyptology: Exploring Identity in Ancient Egypt". In Candelora, Danielle; Ben-Marzouk, Nadia; Cooney, Kathyln (eds.). Ancient Egyptian society : challenging assumptions, exploring approaches. Abingdon, Oxon. pp. 101–111. ISBN 9780367434632.

Popular news articles often distill academic research into a more basic form, but in the case of aDNA, this succinctness may be drawing a much stronger conclusion than the one presented in the scientific report. Indeed, reports based on three male mummies from a single site in Egypt, whose genomes were compared to non-contemporary ancient samples from the Near East and modern Egyptian samples, concluded that ancient Egyptians may have had more in common genetically with the Middle East than African populations (see discussion in Keita, this volume; Schuenemann et al. 2017).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Ehret, Christopher (20 June 2023). Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 83–86, 167–169. ISBN 978-0-691-24409-9. Archived from the original on 22 March 2023. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ↑ Ehret, Christopher (20 June 2023). Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE. Princeton University Press. pp. 97, 167. ISBN 978-0-691-24410-5.