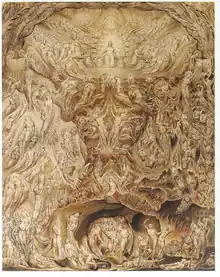

A Vision of the Last Judgement is a painting by William Blake that was designed in 1808 before becoming a lost artwork. The painting was to be shown in an 1810 exhibition with a detailed analysis added to a second edition of his Descriptive Catalogue. This plan was dropped after the exhibition was cancelled, and the painting disappeared. Blake's notes for the Descriptive Catalogue describe various aspects of the work in a detailed manner, which allow the aspects of the painting to be known. Additionally, earlier designs that reveal similar Blake depiction of the Last Judgement have survived, and these date back to an 1805 precursor design created for Robert Blair's The Grave. In addition to Blake's notes on the painting, a letter written to Ozias Humphrey provides a description of the various images within an earlier design of the Last Judgement.

Origins

Blake claimed to have seen visions throughout his life, and he claimed that they were a common aspect of life. His understanding of these events was, as he explained, similar to the experiences of biblical prophets. In the commentary to A Vision of the Last Judgement, Blake claimed that the image originated in a particular vision he experienced that allowed him to see the host of Heaven praising God. The actual design of A Vision of the Last Judgement was created in 1808 as an expansion of his 1805 work The Day of Judgement. Blake created this work to be used in Blair's The Grave, which was published 1808.[1]

The seven feet by five-foot painting was to be shown in an 1810 exhibit of Blake's work, but the exhibit was cancelled after problems resulting from an 1809 exhibit of his works. The actual painting was lost, but earlier versions of the work survived.[2] These include an 1808 watercolour version made for Elizabeth Ilive, wife of George Wyndham, 3rd Earl of Egremont, that was displayed at their Petworth House. A similar illustration in pencil and ink became part of the Rosenwald Collection.[2] Other editions included watercolours made for Thomas Butts in 1806, 1807, and 1809, one for John Flaxman in 1806 (lost), and an 1809 unsold version in tempera. These are in addition to The Day of Judgement made for Blair's The Grave.[3]

The painting was to be discussed in Blake's Descriptive Catalogue, a work that, in 1809, described Blake's feelings about various painters and poets in addition to descriptions of his own works and their various meanings. Blake planned to create another edition for the 1810 collection but the plan was stopped after the exhibition was cancelled. Notes for what Blake planned to write for the works A Vision of the Last Judgement and Public Address survived. The notes were discovered by William Michael Rossetti and first mentioned in a letter to Horace Scudder on 27 November 1864. Rossetti transcribed the notes for Alexander Gilchrist's The Life of William Blake, an early biography on Blake. One piece of the work was missing: part of page 71 was sent by Rossetti to Scudder.[4] Blake discussed the 1808 watercolour sold to Ilives in two works, a poem, "The Caverns of the Grave Ive Seen", written for Ilives provided by Blake with her design. and a description of Ilives's design for Humphry in January 1808.[5]

Painting

The description provided by Blake to Humphrey explains that the work depicts the resurrection. The top of the work depicts Christ on the Throne of Judgement with Heaven opened up across the painting. Behind Christ are the heads of infants which represent creation coming from Jesus. Christ is surrounded by the four Zoas and seven angels that have vials filled with God's wrath. An image of a tabernacle with a cross inside is depicted above Christ. An image of baptism is to Christ's right and the Last Supper is to Christ's left with both representing eternal life. Further to Christ's right is the resurrection of the just and to the left is the resurrection and subsequent fall of the wicked. Adam and Eve are below Christ, and Abraham and Moses are nearby. Below Moses is Satan wrapped by the Serpent and in the centre is the book of death. At the top is the book of life, and the Christian Church is the figure of a woman on top of the moon.[5]

Blake, in his notes to A Vision of the Last Judgement, describes how his design is to work: "If the Spectator could Enter into these Images in his Imagination approaching them on the Fiery Chariot of his Contemplative Thought [...] then would he arise from his Grave".[6] He relies on the word representation frequently in the work, and he tries to represent action in a visible manner that distances his depiction of the apocalypse from a traditional version that disguises the various components of an apocalyptic vision. To Blake, he must create an image of the Last Judgement, then represent the image, and then describe with a written gloss of the work. This creates a layer of representation that separates the audience from the apocalyptic experience, which undermines the concept of apocalypse as both mysterious and directly experienced.[7]

In discussing the nature of time, Blake wrote in his notes: "The Greeks represented Chronos or Time as a very Aged Man; this is Fable, but the Real Vision of Time is in Eternal Youth. I have, however, somewhat accommodated my Figure of Time to the common opinion, as I myself am also infected with it & my Visions also infected, as I see Time Aged, alas, too much so."[8]

Themes

Blake based his portrayal of the apocalypse on his belief that God's love allowed for a personal apocalypse as part of the human experience.[9] In the notes to the work, he claimed that "whenever any Individual Rejects Error & Embraces Truth a Last Judgement passes upon that Individual".[10] This idea is connected to views of David Hartley of the "pure disinterested love of God", and appears in other works by Blake, including his Jerusalem.[11] Also, Blake's Milton describes the process that an individual goes through during an apocalypse, which includes having to confront their errors and their flaws. There is no peace during the struggle, as it involves a direct interaction between contrary views that would eventually establish the new state.[12]

On the details in the painting, Blake claimed that each component had a specific meaning that provides an allegory-like dimension to the work. Blake dismissed the idea of using allegory within his works except, as he wrote in a letter to Butts, 6 July 1803,[13] "Allegory Address'd to the intellectual powers, while it is altogether hidden from the Corporeal Understanding, is My Definition of the Most Sublime Poetry".[14]

Blake's philosophical interpretation of time is similar to Samuel Taylor Coleridge's depiction of the relationship between time and the state of limbo within his poem "Limbo". Both claim that their understanding of time is connected to the common, contemporary view, but they alter their perspective of time within their works to that of an older person. The figure of time appears in other works by Blake, including as the figure Los and in the illustration Blake made for Edward Young's Night Thoughts.[15]

Notes

- ↑ Bentley 2003 pp. 20, 316

- 1 2 Johnson and Grant 1979 pp. 408–409

- ↑ Bentley 2003 Plate 109

- ↑ Damon 1988 pp. 102–103, 437

- 1 2 Bentley 2003 pp. 316–317

- ↑ Goldsmith 1993 qtd p. 151

- ↑ Goldsmith 1993 p. 152

- ↑ Stevenson 1996 qtd. p. 83

- ↑ Mee 2005 p. 290

- ↑ Mee 2005 qtd. p. 290

- ↑ Mee 2005 pp. 289–290

- ↑ Behrendt 1983 p. 23

- ↑ Johnson and Grant 1979 p. 409

- ↑ Johnson and Grant 1979 qtd. p. 409

- ↑ Stevenson 1996 pp. 82–83

References

- Behrendt, Stephen. The Moment of Explosion. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1983.

- Bentley, G. E. The Stranger from Paradise. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003.

- Damon, S. Foster. A Blake Dictionary. Hanover: University Press of New England, 1988.

- Goldsmith, Steven. Unbuilding Jerusalem. Ithaca: Cornell University, 1993.

- Johnson, Mary and Grant, John (eds). Blake's Poetry and Designs. New York: W. W. Norton, 1979.

- Mee, Jon. Romanticism, Enthusiasm, and Regulation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Stevenson, Warren. Romanticism and the Androgynous Sublime. London: Associated University Presses, 1996.