| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

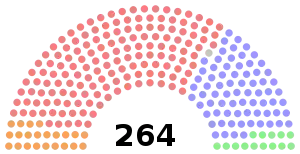

264 seats in the House of Commons 133 seats needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opinion polls | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 75.7%[1] ( | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

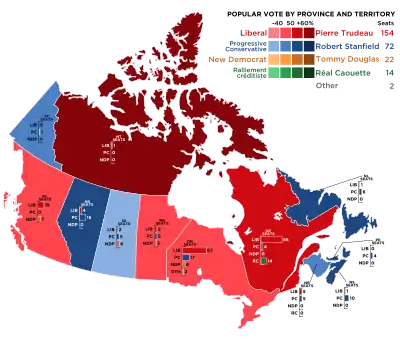

Popular vote by province, with graphs indicating the number of seats won. As this is an FPTP election, seat totals are not determined by popular vote by province but instead via results by each riding. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

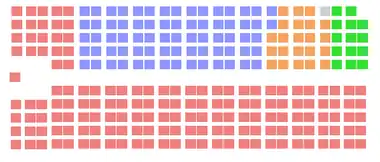

The Canadian parliament after the 1968 election | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The 1968 Canadian federal election was held on June 25, 1968, to elect members of the House of Commons of Canada of the 28th Parliament of Canada.

In April 1968, Prime Minister Lester Pearson of the Liberal Party resigned as party leader as a result of declining health and failing to win a majority government in two attempts. He was succeeded by his Minister of Justice and Attorney General Pierre Trudeau, who called an election immediately after becoming prime minister. Trudeau's charisma appealed to Canadian voters; his popularity became known as "Trudeaumania" and helped him win a comfortable majority. Robert Stanfield's Progressive Conservatives lost seats whereas the New Democratic Party's support stayed the same.

Background

Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson had announced in December 1967 that he would retire early in the following year, calling a new leadership election for the following April to decide on a successor. In February 1968, however, Pearson's government nearly fell before the leadership election could even take place, when it was unexpectedly defeated on a tax bill. Convention dictated that Pearson would have been forced to resign and call an election had the government been defeated on a full budget bill, but after taking legal advice, Governor General Roland Michener decreed that he would only ask for Pearson's resignation if an explicit motion of no confidence were called in his government. Ultimately, the New Democratic Party and Ralliement créditiste were not willing to topple the government over the issue, and even had they done so, Pearson would have been entitled to advise Michener not to hold an election until after the new Liberal leader had been chosen, but the incident made it clear that Pearson's successor could not feasibly hope to hold out until the next statutory general election date of November 1970, and would in all likelihood be forced to call an election much sooner.[2]

Pierre Trudeau, who was a relative unknown until he was appointed to the cabinet by Pearson, won a surprise victory over Paul Martin Sr., Paul Hellyer and Robert Winters in the party's leadership election on April 6. He was sworn in as prime minister on April 20.

Parties and campaigns

Liberals

As had been widely expected, Trudeau called an immediate election after he was sworn in as prime minister. The charismatic, intellectual, handsome, single, and fully bilingual Trudeau soon captured the hearts and minds of the nation, and the period leading up to the election saw such intense feelings for him that it was dubbed "Trudeaumania." At public appearances, he was confronted by screaming girls, something never before seen in Canadian politics. The Liberal campaign was dominated by Trudeau's personality. Liberal campaign ads featured pictures of Trudeau inviting Canadians to "Come work with me", and encouraged them to "Vote for New Leadership for All of Canada". The substance of the campaign was based upon the creation of a "just society", with a proposed expansion of social programs.

Progressive Conservatives

The principal opposition to the Liberals was the Progressive Conservative Party (PC Party) led by Robert Stanfield, who had previously served as premier of Nova Scotia. The PCs started the election campaign with an internal poll showing them trailing the Liberals by 22 points.[3]

Stanfield proposed introducing guaranteed annual income, though failed to explain the number of citizens that would be covered, the minimum income level, and the cost to implement it. Due to concerns that the term "guaranteed annual income" sounded socialist, he eventually switched to using the term "negative income tax". These mistakes made the policy impossible for voters to understand and harmed the PCs. What also damaged the PCs was the idea of deux nations (meaning that Canada was one country housing two nations - French Canadians and English-speaking Canadians). Marcel Faribault, the PCs' Quebec lieutenant and MP candidate, was unclear on whether he supported or opposed deux nations and Stanfield did not drop him as a candidate. This led to the Liberals positioning themselves as the party that supported one Canada. In mid-June, they ran a full-page newspaper advertisement that implied that Stanfield supported deux nations; Stanfield called the ad "a deliberate lie" and insisted he supported one Canada.[4]

New Democratic Party

On the left, former long-time Premier of Saskatchewan Tommy Douglas led the New Democratic Party, but once again failed to make the electoral break-through that was hoped for when the party was founded in 1960. Douglas gained a measure of personal satisfaction - the ouster of Diefenbaker had badly damaged the PC brand in Saskatchewan, and played a major role in allowing the NDP to overcome a decade of futility at the federal level in Saskatchewan to win a plurality of seats there. Nevertheless, these gains were balanced out by losses elsewhere in the country. Under the slogan, "You win with the NDP", Douglas campaigned for affordable housing, higher old age pensions, lower prescription drug prices, and a reduced cost of living. However, the NDP had difficulty running against the left-leaning Trudeau, who was himself a former supporter of the NDP. Douglas would step down as leader in 1971, but remains a powerful icon for New Democrats.

Leaders' debate

This was the first Canadian federal election to hold a leaders debate, on June 9, 1968. The debate included Trudeau, Stanfield, Douglas, and in the latter part Réal Caouette, with Caouette speaking French and Trudeau alternating between the languages. A.B. Patterson, leader of the Social Credit Party was not invited to this debate. The assassination of Robert F. Kennedy three days before cast a pall over the proceedings, and the stilted format was generally seen as boring and inconclusive.[5]

Electoral system

In this election, for the first time since Confederation, all the MPs were elected as the single member for their district, through First past the post. Previously some had always been elected in multi-member ridings through Block Voting. From here on, single-winner First past the post would be the only electoral system used to elect MPs.[6]

National results

The results of the election were sealed when on the night before the election a riot broke out at the St. Jean Baptiste Day parade in Montreal. Protesting the prime minister's attendance at the parade, supporters of Quebec independence yelled Trudeau au poteau [Trudeau to the gallows], and threw bottles and rocks. Trudeau, whose lack of military service during World War II had led some to question his courage, firmly stood his ground, and did not flee from the violence despite the wishes of his security escort. Images of Trudeau standing fast to the thrown bottles of the rioters were broadcast across the country, and swung the election even further in the Liberals' favour as many English-speaking Canadians believed that he would be the right leader to fight the threat of Quebec separatism.

The Social Credit Party, having lost two of the five seats it picked up at the previous election via defections (including former leader Robert N. Thompson, who defected to the Tories in March 1967), lost its three remaining seats. On the other hand, the Ralliement des créditistes (Social Credit Rally), the Québec wing of the party that had split from the English Canadian party, met with great success. The créditistes were a populist option appealing to social conservatives and Québec nationalists. They were especially strong in rural ridings and amongst poor voters. Party leader Réal Caouette campaigned against poverty, government indifference, and "la grosse finance" (big finance). The Canadian social credit movement would never win seats in English Canada again.

Atlantic Canada bucked the national trend, with the Tories making large gains in that region and winning pluralities in all four Atlantic provinces. In that region, the Tory brand was strengthened by the leadership of former Nova Scotian premier Stanfield. Voters in Newfoundland, who were growing increasingly weary of their Liberal administration under founding Premier Joey Smallwood, voted PC for the first time since entering Confederation.

| Party | Party leader | # of candidates |

Seats | Popular vote | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1965 | Dissolution | Elected | % Change | # | % | Change | ||||

| Liberal | Pierre Trudeau | 262 | 131 | 128 | 154 | +18.3% | 3,686,801 | 45.37% | +5.18pp | |

| Progressive Conservative | Robert Stanfield | 263 | 97 | 94 | 72 | -25.8% | 2,554,397 | 31.43% | -0.98pp | |

| New Democratic Party | Tommy Douglas | 263 | 21 | 22 | 22 | +4.8% | 1,378,263 | 16.96% | -0.95pp | |

| Ralliement créditiste | Réal Caouette | 72 | 9 | 8 | 14 | +55.6% | 360,404 | 4.43% | -0.22pp | |

| Independent | 29 | 1 | 2 | 1 | - | 36,543 | 0.45% | -0.23pp | ||

| Liberal-Labour | Pierre Trudeau[NB 1] | 1 | 1 | 10,144 | 0.12% | |||||

| Social Credit | A.B. Patterson | 32 | 5 | 4 | - | -100% | 68,742 | 0.85% | -2.82pp | |

| Independent Liberal | 11 | - | - | - | - | 16,785 | 0.21% | -0.01pp | ||

| Communist | William Kashtan | 14 | - | - | - | - | 4,465 | 0.05% | x | |

| Independent PC | 5 | 1 | - | - | -100% | 2,762 | 0.03% | -0.14pp | ||

| Démocratisation Économique | 5 | - | 2,651 | 0.03% | ||||||

| Franc Lib | 1 | - | 2,141 | 0.03% | ||||||

| Independent Conservative | 1 | - | - | - | - | 632 | 0.01% | x | ||

| Reform | 1 | - | 420 | 0.01% | ||||||

| Rhinoceros | Cornelius I | 1 | - | 354 | x | x | ||||

| Conservative | 1 | - | - | - | - | 339 | x | x | ||

| Esprit social | H-G Grenier | 1 | - | - | - | - | 311 | x | x | |

| Socialist Labour | 1 | - | - | - | - | 202 | x | x | ||

| Republican[NB 2] | 1 | - | 175 | x | ||||||

| New Canada | Fred Reiner | 1 | - | 148 | x | |||||

| National Socialist | 1 | - | 89 | x | ||||||

| Vacant | 6 | |||||||||

| Total | 967 | 265 | 265 | 264 | -0.4% | 8,126,768 | 100% | |||

| Sources: http://www.elections.ca History of Federal Ridings since 1867, Toronto Star, June 24, 1968. | ||||||||||

Notes:

"% change" refers to change from previous election

x - less than 0.005% of the popular vote

"Dissolution" refers to party standings in the House of Commons immediately prior to the election call, not the results of the previous election.

- ↑ John Mercer Reid won as a Liberal-Labour candidate but remained a member of the Liberal Party caucus, led by Pierre Trudeau.

- ↑ The Republican Party also took credit for a second candidate, who received 420 votes. (Vancouver Sun, June 26, 1968, "Republicans Claim Win", p. 15)

Vote and seat summaries

Results by province

| Party name | BC | AB | SK | MB | ON | QC | NB | NS | PE | NL | NT | YK | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal | Seats: | 16 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 63 | 56 | 5 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | - | 154 | |

| Popular vote: | 41.8 | 35.7 | 27.1 | 41.5 | 46.2 | 53.6 | 44.4 | 38.0 | 45.0 | 42.8 | 63.8 | 47.0 | 45.4 | ||

| Progressive Conservative | Seats: | - | 15 | 5 | 5 | 17 | 4 | 5 | 10 | 4 | 6 | - | 1 | 72 | |

| Vote: | 18.9 | 51.0 | 37.0 | 31.4 | 32.0 | 21.4 | 49.7 | 55.2 | 51.8 | 52.7 | 23.4 | 48.0 | 31.4 | ||

| New Democratic | Seats: | 7 | - | 6 | 3 | 6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 22 | |

| Vote: | 32.6 | 9.4 | 35.7 | 25.0 | 20.6 | 7.5 | 4.9 | 6.7 | 3.2 | 4.4 | 12.8 | 5.0 | 17.0 | ||

| Ralliement créditiste | Seats: | 14 | - | 14 | |||||||||||

| Vote: | 16.4 | 0.7 | 4.4 | ||||||||||||

| Independent | Seats: | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | ||||||

| Vote: | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.4 | |||||||

| Liberal-Labour | Seats: | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Vote: | 0.3 | 0.1 | |||||||||||||

| Total seats: | 23 | 19 | 13 | 13 | 88 | 74 | 10 | 11 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 264 | ||

| Parties that won no seats: | |||||||||||||||

| Social Credit | Vote: | 6.4 | 1.9 | 1.5 | xx | 0.1 | 0.8 | ||||||||

| Independent Liberal | Vote: | 1.5 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | ||||||||||

| Communist | Vote: | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | xx | 0.1 | |||||||

| Independent PC | Vote: | 0.2 | xx | xx | 0.1 | 0.1 | xx | ||||||||

| Démocratisation Écon. | Vote: | 0.1 | xx | ||||||||||||

| Franc Lib | Vote: | 0.1 | xx | ||||||||||||

| Independent Cons. | Vote: | 0.2 | xx | ||||||||||||

| Reform | Vote: | 0.1 | xx | ||||||||||||

| Rhinoceros | Vote: | xx | xx | ||||||||||||

| Conservative | Vote: | xx | xx | ||||||||||||

| Espirit social | Vote: | xx | xx | ||||||||||||

| Socialist Labour | Vote: | xx | xx | ||||||||||||

| Republican | Vote: | xx | xx | ||||||||||||

| New Canada | Vote: | xx | xx | ||||||||||||

| National Socialist | Vote: | xx | xx | ||||||||||||

Notes

xx - less than 0.05% of the popular vote.

- Voter turnout: 75.7% of the eligible population voted.

See also

References

- ↑ Pomfret, R. "Voter Turnout at Federal Elections and Referendums". Elections Canada. Elections Canada. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ↑ Robertson, Gordon; Memoirs of a Very Civil Servant; pp299-301

- ↑ Stevens (1973), p. 213.

- ↑ Stevens (1973), p. 216–221.

- ↑ CBC Archives

- ↑ Parliamentary Guide 1969, p. 333-334; Parliamentary Guide 2011, p. 432-433

- ↑ Only contested seats in Quebec and Restigouche—Madawaska in New Brunswick.

Further reading

- Argyle, Ray (2004). Turning Points: The Campaigns that Changed Canada 2004 and Before. Toronto: White Knight Publications. ISBN 978-0-9734186-6-8.

- Beck, James Murray (1968). Pendulum of Power; Canada's Federal Elections. Scarborough: Prentice-Hall of Canada. ISBN 978-0-13-655670-1.

- Peacock, Donald (1968). Journey to Power: The Story of a Canadian Election. Toronto: The Ryerson Press. ISBN 978-0-7700-0253-4.

- Saywell, John, ed. (1969). Canadian Annual Review for 1968. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-1649-2.

- Stevens, Geoffrey (1973). Stanfield. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 9780771083587.

- Sullivan, Martin (1968). Mandate '68: The Year of Pierre Elliott Trudeau. Toronto: Doubleday.

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)