| |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | September 25, 1932 |

| Dissipated | October 2, 1932 |

| Category 4 hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 145 mph (230 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 943 mbar (hPa); 27.85 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 272 |

| Damage | >$35.8 million (1932 USD) |

| Areas affected | Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1932 Atlantic hurricane season | |

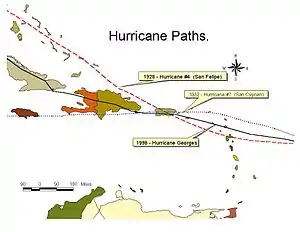

The 1932 San Ciprián hurricane[lower-alpha 1] was one of the strongest tropical cyclones in the history of Puerto Rico. The center of the storm traversed the island on an east-to-west path in late September 1932, killing 272 people and inflicting at least $35 million in damage.[lower-alpha 2] Winds in San Juan, Puerto Rico, were estimated to have reached at least 120 mph (190 km/h), causing extensive destruction. The storm's origins can be traced back to at least September 25, 1932, when it was a tropical storm east of the Windward Islands. Moving west as a compact tropical cyclone, it rapidly intensified as it moved across the Virgin Islands the following day before ultimately making landfall on September 27 in Ceiba, Puerto Rico, at a peak intensity equivalent to that of a Category 4 hurricane on the modern Saffir–Simpson scale. The hurricane diminished for the remainder of its duration, leaving Puerto Rico and brushing the southern coast of Hispaniola. The cyclone passed near Jamaica on September 29 and moved ashore British Honduras on October 1 as a tropical storm, dissipating the next day over southeastern Mexico.

The hurricane brought strong winds to parts of the Virgin Islands. In Saint Thomas, wires and trees were blown down and homes were damaged. Ships also sank in the Saint Thomas harbor, as well as at Tortola. Property losses on Saint Thomas were estimated to have exceeded $200,000 and 15 people were killed. Most of the damage caused by the San Ciprián hurricane occurred in Puerto Rico, particularly along the island's northern half. The powerful winds caused the destruction of numerous buildings. Over 40,000 homes were destroyed throughout the U.S. territory, contributing to a $15.6 million property damage toll and rendering 25,000 families homeless. Heavy losses were wrought upon crops, particularly to citrus and coffee. The hurricane killed 257 people in Puerto Rico and injured another 4,820. Economic losses stemming from the devastation were equivalent to 20 percent of Puerto Rico's gross income.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

The presence of unusually high air pressures throughout the Atlantic and eastern North America caused the 1932 San Ciprián hurricane to take an atypical path directed towards the west and west-southwest over its duration.[6] Details about the hurricane's genesis are unclear due to a lack of contemporaneous weather observations. In 2012, the Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (AOML) investigated the storm's history,[lower-alpha 3] determining that the hurricane's progenitor had developed into a tropical storm with sustained winds of 60 mph (97 km/h) by 06:00 UTC on September 25, 1932.[8] At that point, the storm was amid a period of intensification and centered approximately 340 mi (550 km) east of Antigua. Its winds increased as it moved west, reaching hurricane-force by 12:00 UTC on September 25.[10] Early the next day, the hurricane passed near Antigua and Saint Barthelemy, and later between Saint Thomas and Saint Croix, tracking west-northwest at roughly 10 mph (16 km/h).[6] Around 13:00 UTC on September 26, the center of the storm passed near Saba with winds of 140 mph (230 km/h);[lower-alpha 4] the steep pressure gradient measured on that island was indicative of a small and rapidly intensifying hurricane.[8]

At around 04:00 UTC on September 27, the compact hurricane made landfall on Puerto Rico near Ensenada Honda in the municipality of Ceiba. Upon moving ashore, the hurricane had sustained winds estimated at 145 mph (233 km/h)[lower-alpha 4] and a minimum central pressure of 943 mbar (hPa; 27.85 inHg), equivalent to a Category 4 hurricane on the modern Saffir–Simpson scale. The region of hurricane-force winds was likely no larger than 23 mi (37 km) in diameter upon landfall, with a radius of maximum winds likely smaller than 12 mi (19 km). The storm's center tracked over Puerto Rico for seven hours on an east-to-west course before emerging into the Caribbean Sea off Aguadilla.[8] Land interaction with Puerto Rico caused the storm's maximum winds to decrease to 105 mph (169 km/h);[lower-alpha 4] the hurricane maintained this strength until it struck the southern ends of the Dominican Republic and Haiti on September 28.[6][8][10] This second landfall weakened the system significantly, reducing the winds to 45 mph (72 km/h).[lower-alpha 4][8] The storm took a slightly south of west heading for the rest of its duration, passing near Jamaica on September 29.[10] According to the AOML, the storm might have weakened to a tropical depression between September 29–30 while traversing the western Caribbean.[8] The tropical storm reorganized slightly upon making its final landfall south of Belize City in British Honduras at around 18:00 UTC on October 1 with winds of 45 mph (72 km/h).[lower-alpha 4] It progressed west-southwest into southeastern Mexico, weakening before dissipating on October 2.[8]

Effects

Virgin Islands

The hurricane's small size was evidenced by wind observations at Saint Thomas and Saint Croix, which are located roughly 45 mi (72 km) apart. Despite the center of the hurricane passing between the islands, neither island experienced hurricane-force winds, their speeds only reaching 60 mph (97 km/h).[8][6] The United States Weather Bureau characterized the damage on Saint Barthélemy, Saint John, Saint Thomas, and Tortola as "moderate".[6] Legislative elections in the Virgin Islands were postponed due to the inclement conditions. Two passenger-filled sloops in Tortola were lost.[13] Estimated winds of 60–90 mph (97–145 km/h) swept across Saint Barthelemy.[6] Radio antennas were blown down by the winds in Saba.[6] The firing of warning guns on Saint Thomas 90 minutes before the storm's arrival allowed the island's populace to seek shelter. Many houses were damaged and wires and trees were blown down on the island. Small ships capsized in the Saint Thomas harbor. Fifteen people were killed and total property losses on the island were estimated to exceed $200,000.[14][15] The destruction of huts and crops rendered hundreds of people destitute. The Red Cross and the Saint Thomas government allocated $6,000 total to relief efforts.[16]

Puerto Rico

The Weather Bureau office in San Juan was first made aware of the storm's presence on September 26, following a report of the passage of a "moderate disturbance" near Antigua.[6] Its first storm bulletin was issued that evening after the center of the storm passed between Saint Thomas and Saint Croix, noting the rapidity of the storm's movement and its small size.[6][17] This and subsequent bulletins were disseminated in Puerto Rico by the territorial government, the U.S. Navy, and local radio station WKAQ. The San Juan Weather Bureau office lauded these bodies in their report on the storm published in the Monthly Weather Review, writing that "the loss of life and property damaged were materially reduced" due to their efforts.[6] There were 18 hours of advance warning for San Juan before the hurricane struck.[18] The bureau continued to issue advisories concerning the storm twice daily through October 1.[6]

At the beginning of the 1932 Atlantic hurricane season, the Governor of Puerto Rico, James R. Beverly, directed mayors in the territory to organize municipal emergency committees, requiring each to hoist hurricane flag signals at the cathedrals and city halls of every town whenever a hurricane warning was in effect. Mayors and police forces in Puerto were advised by the Weather Bureau's first statements on the storm to begin safeguarding lives and property. A meeting was held on the afternoon of September 26 between the governor, heads of executive departments, the manager of the Puerto Rican chapter of the American Red Cross, and other prominent citizens to formulate plans of actions for possible emergencies arising from the hurricane's passage; these included the mobilization of crews to repair communications infrastructure and police-assisted evacuation of vulnerable people into the sturdiest buildings.[4] The American Red Cross in the continental U.S. also prepared to send aid to Puerto Rico when necessary.[19]

Forty-nine municipalities of Puerto Rico were affected by the storm to varying degrees, with devastation wrought across the northern half of the territory.[4] The hurricane's effects killed 257 people;[4] most of these fatalities were due to the collapse of buildings, with wind-blown debris and drownings also responsible for some deaths.[6] Over 4,820 others were injured.[4] Though people took shelter in buildings thought to be safe, only well-built masonry and concrete structures withstood the storm in the hardest-hit areas. Concrete buildings made of concrete with a water-to-cement ratio and improperly or poorly anchored roofs were destroyed, killing many. Homes with corrugated iron sheet roofs attached using smooth or twisted nails, common in San Juan, were unroofed.[6] In total, 45,554 houses were razed and another 47,876 were partially destroyed.[4] The severity of the damage was equivalent to that of an F3 tornado on the Fujita scale.[8] Writing to the United States Secretary of War in 1933, Beverly described the damage was more severe than the 1928 San Felipe hurricane for the areas affected.[4] Nearly 500,000 animals were also killed, including cows, goats, horses, pigs, and poultry.[4]

The steamships Jean and Acacia took refuge at Ensenada Honda, where the hurricane made landfall. Both ships were grounded by the storm but were refloated after unloading cargo. Several pier buildings at the Port of San Juan sustained heavy damage. The three-masted schooner Gaviota was wrecked in the harbor. The bridge and ship's boats of another vessel in the harbor were blown away.[6] Many smaller ships along the waterfront were driven aground.[20] Telephone and telegraph lines between San Juan and the eastern parts of Puerto Rico were disrupted on the night of September 26. The worst of the storm reached San Juan shortly after midnight on the morning of September 27 and lasted for about three hours;[4] hurricane-force winds lasted for six hours.[18] Winds of at least 120 mph (190 km/h) occurred in San Juan, though the local measurement tower measured a peak wind of 66 mph (106 km/h) before it was toppled by the storm.[6] In San Juan, Hato Rey, and Río Piedras, hundreds of homes were blown away and trees were uprooted.[4] Reports indicated that all homes collapsed in Fajardo and Toa Alta. Many small towns outside of the San Juan area were left in similar circumstances.[21] All communication and electric poles and wires were knocked down.[4] WKAQ's radio towers lay toppled and contorted by the wind.[20] The carnage littered streets with debris.[4]

Rainfall totals in Puerto Rico were lower overall than in other hurricanes of similar strength. The maximum total of 16.70 in (424 mm) was measured in Maricao.[6] Damage to both property and crops amounted to $35.6 million, with $15.6 million inflicted upon property and $20 million inflicted upon crops. The Puerto Rican Department of Commerce that the damage parlayed into $31.2 million in economic losses for agriculture.[4] The main citrus-producing regions of Puerto Rico were located within the swath of the heaviest damage; its losses accounted for the largest proportion of crop losses. Though the main coffee tree plantations did not experience the storm's strongest winds, they were heavily damaged by fallen banana trees; banana trees had been planted to provide temporary shading for the new coffee crop following the 1928 San Felipe hurricane but were susceptible to moderate winds. The toll inflicted on citrus and coffee trees delayed their harvests by several years. The hurricane rendered other crops a total loss, though to an extent recoverable within a growing season.[6] Approximately $2.4 million worth of agricultural plantations and structures constructed using recovery funds from the 1928 hurricane were destroyed.[22] Forests along the Sierra de Luquillo were defoliated and exhibited high tree mortality after being lashed by the heavy rains and strong winds.[23] East of the Puerto Rican mainland, Culebra and Vieques also sustained heavy damage.[6]

Workers from the Puerto Rican Department of the Interior, assisted by prisoners and volunteers, quickly cleared roads of debris once the storm passed. National Guard and Red Cross personnel were promptly dispatched into the affected areas to aid recovery efforts; medical and food supplies were distributed in the larger impacted municipalities within 24 hours of the storm's passage.[4] Some of the relief efforts were also managed by the Puerto Rican Hurricane Relief Commission that was formed in response to the 1928 hurricane.[22] For the 1932 storm, a Hurricane Relief and Rehabilitation Commission was formed on September 27 in cooperation with the Red Cross, split into an executive committee and two subcommittees. One subcommittee was tasked with enforcing price controls while the other was tasked with raising relief funds for immediate purchases of materials and to supplement the Red Cross's efforts; nearly $75,000 was collected by this second committee. The funds augmented an emergency fund established by the Puerto Rican government in April 1932; $165,000 in relief was sourced from this fund, including a $50,000 loan to the Fruit Growers Cooperative Credit Association for the recovery of the citrus crop and acquisition of fertilizer. Food and shelter relief was administered by the Red Cross. Additional supplies were made available to these committees by the American military stationed in Puerto Rico. Two reconnaissance flights were arranged on September 27 and 28 to better determine the extent and severity of the damage across northern Puerto Rico. Teachers were enlisted by the Department of Education to appraise the total property damage while crop damage was tallied by the Commissioner of Agriculture and Commerce. The Red Cross reported that 76,925 families were in "actual distress" due to the hurricane.[4] The destruction of homes rendered 25,000 families homeless.[24] Total economic losses from the storm were equivalent to 20 percent of Puerto Rico's gross income.[25]

Elsewhere

In the Dominican Republic, the hurricane's approach triggered fears of a second disaster as that country was still recovering from the destruction by another hurricane two years earlier. The concern prompted residents to close businesses and evacuate; some took to nearby churches for shelter.[26] The 1932 storm produced 90 mph (140 km/h) winds in San Pedro de Macorís and 50 mph (80 km/h) winds in Santo Domingo.[6] Agricultural sectors of Santo Domingo sustained "considerable damage".[27] Hurricane warning flags were raised in Jamaica on September 29. Storeowners secured their vulnerable storefronts and awnings while ships at harbor were moved to shelter.[28] The storm ultimately passed south of Jamaica with little consequence.[29] Signal flags warning of the storm's approach were first hoisted in the British Honduras on October 1, leading to the closure of businesses and the commencement of storm preparations.[30] However, the storm moved over the British Honduras with little force, causing no damage.[31]

See also

- 1867 San Narciso hurricane – took a similar track through the Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico, causing 811 deaths

- 1876 San Felipe hurricane – tracked across the Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico as a major hurricane

- Hurricane Georges – the first hurricane after 1932 to take an east-to-west path across Puerto Rico[32]

- Hurricane Maria – the first storm after 1932 to strike Puerto Rico with at least Category 4 hurricane winds[33]

Notes

- ↑ The Puerto Rican tradition of referring to intense hurricanes by the names of Catholic saints being commemorated on the corresponding feast days was among the earliest informal tropical cyclone naming systems, and lasted for centuries prior to the introduction of standardized naming conventions.[1][2][3] The 1932 San Ciprián hurricane struck Puerto Rico on the feast day of Saint Cyprian, September 26.[4] Although the storm is commonly known as San Ciprián, this is a misnomer; the correct translation for Saint Cyprian in Spanish is San Cipriano.[5]

- ↑ All monetary values are in 1932 United States dollars unless otherwise indicated.

- ↑ The AOML, through its Hurricane Research Division, analyzed the system in 2012 as part of a project to reevaluate the official hurricane database maintained by the National Hurricane Center.[7][8][9] Their assessment of the 1932 San Ciprián hurricane made alterations to the storm's track and intensity; for instance, the storm's intensity at its Puerto Rico landfall was originally listed as equivalent to a Category 2 hurricane.[8]

- 1 2 3 4 5 HURDAT, the official database for the intensities and tracks of Atlantic tropical cyclones,[11] lists the maximum sustained winds of storms to the nearest five knots.[12] Conversions to miles per hour (mph) and kilometers per hours (km/h) for values drawn from this database are derived from the original value in knots and rounded to the nearest five.

References

- ↑ "Tropical Cyclone Naming History and Retired Names". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- ↑ Yanez, Anthony (September 7, 2017). "From Adrian to Zelda: A History of Hurricane Names". NBC4 Southern California. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- ↑ "Tropical Cyclone Names". NWS JetStream. National Weather Service. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Beverly, James R. (July 1, 1933). "Thirty-Third Annual Report of the Governor of Puerto Rico 1933 (Excerpts)". Puerto Rico in the Great Depression. San Juan, Puerto Rico: Government of Puerto Rico. Hurricane of 1932. Archived from the original on July 7, 2001. Retrieved April 8, 2020 – via Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt Institute.

- ↑ "Huracanes y Tormentas Tropicales Que Han Afectado a Puerto Rico" (PDF). San Juan, Puerto Rico: Agencia Estatal de Puerto Rico para la Gestión de Emergencias y Administración de Desastres. pp. 12–13. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 12, 2009. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Humphreys, W. J., ed. (September 1932). "West Indian Hurricanes of August and September, 1932" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. San Juan, Puerto Rico: United States Weather Bureau. 60 (9): 178–179. Bibcode:1932MWRv...60..177.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1932)60<177:TTSOAI>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved April 3, 2020 – via National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

- ↑ Landsea, Christopher W.; Hagen, Andrew; Bredemeyer, William; Carrasco, Cristina; Glenn, David A.; Santiago, Adrian; Strahan-Sakoskie, Donna; Dickinson, Michael (August 2014). "A Reanalysis of the 1931–43 Atlantic Hurricane Database". Journal of Climate. Boston, Massachusetts: American Meteorological Society. 27 (16): 6093–6118. Bibcode:2014JCli...27.6093L. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-13-00503.1. S2CID 1785238.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Landsea, Chris; Anderson, Craig; Bredemeyer, William; Carrasco, Cristina; Charles, Noel; Chenoweth, Michael; Clark, Gil; Delgado, Sandy; Dunion, Jason; Ellis, Ryan; Fernandez-Partagas, Jose; Feuer, Steve; Gamanche, John; Glenn, David; Hagen, Andrew; Hufstetler, Lyle; Mock, Cary; Neumann, Charlie; Perez Suarez, Ramon; Prieto, Ricardo; Sanchez-Sesma, Jorge; Santiago, Adrian; Sims, Jamese; Thomas, Donna; Lenworth, Woolcock; Zimmer, Mark (May 2015). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Metadata). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 1932 Storm #9 - 2012 Revision. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- ↑ "Re-Analysis Project". Hurricane Research Division. Miami, Florida: Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. December 2019. Retrieved April 4, 2020.

- 1 2 3 "1932 Major Hurricane NOT_NAMED (1932269N17303)". International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS). Asheville, North Carolina: University of North Carolina at Asheville. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- ↑ Landsea, Chris; Franklin, James; Beven, Jack (May 2015). "The revised Atlantic hurricane database (HURDAT2)" (PDF). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ↑ "Original HURDAT Format". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ↑ "Virgin Islands Are Struck by Tropical Storm". The News-Herald. No. 16047. Franklin, Pennsylvania. United Press. September 27, 1932. p. 1. Retrieved April 10, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Southern Storm Kills 215; Heavy Porto Rico Loss". The Bremen Enquirer. Vol. 47, no. 39. Bremen, Indiana. September 29, 1932. p. 1. Retrieved April 18, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "15 Dead in Virgin Islands". Chicago Daily Tribune. Vol. 91, no. 233. Chicago, Illinois. September 28, 1932. p. 2. Retrieved May 9, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Hundreds Destitute in Virgin Islands". Ames Daily Tribune-Times. Vol. 66, no. 78. Ames, Iowa. United Press. October 1, 1932. p. 8. Retrieved May 6, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Hurricane May Strike Section of Puerto Rico". The News-Herald. No. 16046. Franklin, Pennsylvania. United Press. September 26, 1932. p. 1. Retrieved April 9, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 Cook, Melville T. (1933). "West Indian Hurricanes". The Scientific Monthly. 37 (4): 307–315. ISSN 0096-3771. JSTOR 15604.

- ↑ "Red Cross Prepares to Send Aid to Puerto Rico". The News-Herald. No. 16047. Franklin, Pennsylvania. United Press. September 27, 1932. p. 1. Retrieved April 10, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Storm's Dead Placed at 200 in Puerto Rico". The Miami Herald. Vol. 22, no. 301. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. p. 1. Retrieved April 14, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Beverley, James R. (August 28, 1932). "Hurricane Leaves Heavy Death Toll in Antilles Islands". The Napa Journal. Vol. 79, no. 231. Napa, California. United Press. p. 1. Retrieved April 14, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 Fourth Annual Report of the Puerto Rican Hurricane Relief Commission (Report). Puerto Rican Hurricane Relief Commission. December 2, 1932. pp. 1–6.

- ↑ Crow, Thomas R. (March 1980). "A Rainforest Chronicle: A 30-Year Record of Change in Structure and Composition at El Verde, Puerto Rico". Biotropica. 12 (1): 42–55. doi:10.2307/2387772. JSTOR 2387772.

- ↑ Rodríguez, Havidán (1997). "A Socioeconomic Analysis of Hurricanes in Puerto Rico: An Overview of Disaster Mitigation and Preparedness". Hurricanes: Climate and Socioeconomic Impacts. Springer: 121–143. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-60672-4_7. ISBN 978-3-642-64502-0.

- ↑ Sotomayor, Orlando (July 2013). "Fetal and infant origins of diabetes and ill health: Evidence from Puerto Rico's 1928 and 1932 hurricanes". Economics & Human Biology. Elsevier. 11 (3): 281–293. doi:10.1016/j.ehb.2012.02.009. PMID 22445329.

- ↑ "Santo Domingo Said to Be in Path of Storm Expected Hourly". Clinton Daily Journal and Public. No. 179. Clinton, Illinois. United Press. September 29, 1932. Retrieved April 18, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Repair Begins in Porto Rico". Los Angeles Times. Vol. 51. Los Angeles, California. Associated Press. September 29, 1932. p. 3. Retrieved April 18, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Day of Tense Anxiety". The Daily Gleaner. Vol. 98, no. 228. Kingston, Jamaica. September 29, 1932. p. 6 – via NewspaperArchive.

- ↑ "Hurricane Passes Island on the South". The Daily Gleaner. Vol. 98, no. 229. Kingston, Jamaica. September 30, 1932. p. 1 – via NewspaperArchive.

- ↑ "Capital of Honduras Prepares for Storm". The Evening Sun. Vol. 45. Baltimore, Maryland. Associated Press. October 1, 1932. p. 3. Retrieved April 18, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Honduras Reports No Hurricane Damage". The Muncie Sunday Star. Vol. 56, no. 157. Muncie, Indiana. Associated Press. October 2, 1932. p. 1. Retrieved April 18, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Bennett, Shawn P.; Mojica, Rafael. "Hurricane Georges Preliminary Storm Report". National Weather Service San Juan, Puerto Rico. San Juan, Puerto Rico: National Weather Service. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- ↑ Meyer, Robinson (October 4, 2017). "What's Happening With the Relief Effort in Puerto Rico?". The Atlantic. Retrieved April 8, 2020.