| 1878 Paris | |

|---|---|

The Palais du Trocadéro built for the occasion[1] was reused for the 1900 Universal Exposition, when this postcard was printed | |

| Overview | |

| BIE-class | Universal exposition |

| Category | Historical Expo |

| Name | Exposition universelle de 1878 |

| Building(s) | Palais du Trocadéro |

| Area | 75 hectares (190 acres) |

| Invention(s) | Icemachine, Electric streetlights |

| Visitors | 13,000,000 |

| Participant(s) | |

| Countries | 36 |

| Location | |

| Country | France |

| City | Paris |

| Venue | Avenue des Nations |

| Coordinates | 48°51′44″N 2°17′17.7″E / 48.86222°N 2.288250°E |

| Timeline | |

| Opening | 1 May 1878 |

| Closure | 10 November 1878 |

| Universal expositions | |

| Previous | Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia |

| Next | Melbourne International Exhibition (1880) in Melbourne |

The Exposition Universelle of 1878 (French pronunciation: [ɛkspozisjɔ̃ ynivɛʁsɛl]), better known in English as the 1878 Paris Exposition, was a world's fair held in Paris, France, from 1 May to 10 November 1878, to celebrate the recovery of France after the 1870–71 Franco-Prussian War. It was the third of ten major expositions held in the city between 1855 and 1937.[lower-alpha 1]

Construction

The buildings and the fairgrounds were somewhat unfinished on opening day, as political complications had prevented the French government from paying much attention to the exhibition until six months before it was due to open. However, efforts made in April were prodigious, and by 1 June, a month after the formal opening, the exhibition was finally completed.

This exposition was on a far larger scale than any previously held anywhere in the world. It covered over 66 acres (270,000 m2), the main building in the Champ de Mars and the hill of Chaillot, occupying 54 acres (220,000 m2). The Gare du Champ de Mars was rebuilt with four tracks to receive rail traffic occasioned by the exposition. The Pont d'Iéna linked the two exhibition sites along the central allée. The French exhibits filled one-half of the entire space, with the remaining exhibition space divided among the other nations of the world. Germany was the only major country which was not represented, but there were a few German paintings being exhibited. The United States exhibition was headed by a series of commissioners, which included Pierce M. B. Young, a former United States Congressman and major general in the Confederate States Army and Floyd Perry Baker, a Kansas newspaper editor, as well as other generals, politicians, and celebrities.

The United Kingdom, British India, Canada, Victoria, New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Cape Colony and some of the British crown colonies occupied nearly one-third of the space set aside for nations outside France. The United Kingdom's expenditure was defrayed out of the consolidated revenue; each British colony defrayed its own expenses. The UK display was under the control of a royal commission, of which the Prince of Wales was president.

Views of the Exposition

Aerial view of the Exposition Universelle of 1878

Aerial view of the Exposition Universelle of 1878 Bird's eye view of the Palais du Trocadéro

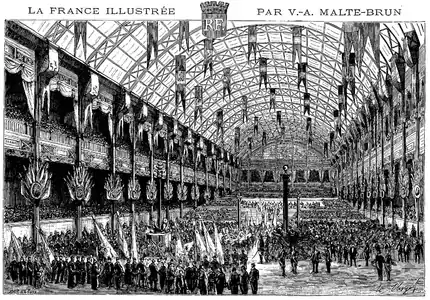

Bird's eye view of the Palais du Trocadéro Interior of the Palais de l'Industrie

Interior of the Palais de l'Industrie

Displays

The exhibition of fine arts and new machinery was on a very large and comprehensive scale, and the Avenue des Nations, a street 730 metres in length, was devoted to examples of the domestic architecture of nearly every country in Europe and several in Asia, Africa and America. The "Gallery of Machines" was a metallic building, an industrial showcase of low transverse arches, designed by the engineer Henri de Dion (1828–78). Many of the buildings and statues were made of staff, a low-cost temporary building material invented in Paris in 1876, which consisted of jute fiber, plaster of Paris, and cement.

On the northern bank of the Seine River, an elaborate palace was constructed for the exhibition at the tip of the Place du Trocadéro. It was a handsome "Moorish" structure, with towers 76 metres in height and flanked by two galleries. It had a Cavaillé-Coll organ which was inaugurated with a concert in which Charles Marie Widor played the premiere of his Symphony for Organ No. 6.[2] The building stood until 1937. On 30 June 1878, the completed head of the Statue of Liberty was showcased in the garden of the Trocadéro palace, while other pieces were on display in the Champs de Mars.

Among the many inventions on display was Alexander Graham Bell's telephone. Electric arc lighting had been installed all along the Avenue de l'Opera and the Place de l'Opera, and in June, a switch was thrown and the area was lit by electric Yablochkov arc lamps, powered by Zénobe Gramme dynamos.[3] Thomas Edison had on display a megaphone and phonograph. International juries judged the various exhibits, awarding medals of gold, silver and bronze. One popular feature was a human zoo, called a "negro village", composed of 400 "indigenous people". And Augustin Mouchot's solar-powered engine converting solar energy into mechanical steam power,[4] he won a gold medal in Class 54 for his works, most notably the production of ice using concentrated solar heat. Henry E. Steinway exhibited a grand piano which "attracted extraordinary attention".[5]

Awards

- Gold award for painting: Jan Matejko, for The Hanging of the Sigismund Bell, Union of Lublin and Wacław Wilczek.

- Gold award for photography: Aimé Dupont

- Gold award for playing cards: New York Consolidated Card Company[6][7]

Félix du Temple's 1874 Monoplane was displayed at the 1878 Exposition Universelle.

Félix du Temple's 1874 Monoplane was displayed at the 1878 Exposition Universelle. The completed head of the Statue of Liberty was showcased.

The completed head of the Statue of Liberty was showcased. Monumental conical clock by Eugène Farcot at the hall of the Galerie d'Iéna of the Palais du Champ-de-Mars

Monumental conical clock by Eugène Farcot at the hall of the Galerie d'Iéna of the Palais du Champ-de-Mars

Attendance

Over 13 million people paid to attend the exposition, making it a financial success. The cost of the enterprise to the French government, which supplied all the construction and operating funds, was a little less than a million British Pounds, after allowing for the value of the permanent buildings and the Trocadéro Palace, which were sold to the city of Paris. The total number of persons who visited Paris during the time the exhibition was open was 571,792, or 308,974 more than came to the French metropolis during 1877, and 46,021 in excess of the visitors during the previous exhibition of 1867. In addition to the general impetus given to French trade, the revenue from customs and duties from the foreign visitors increased by nearly three million sterling compared with the previous year.

Concurrent with the exposition, a number of meetings and conferences were held to gain consensus on international standards. French writer Victor Hugo led the Congress for the Protection of Literary Property, which led to the eventual formulation of international copyright laws. Similarly, other meetings led to efforts to standardize the flow of mail from country to country. The International Congress for the Amelioration of the Condition of Blind People led to the worldwide adoption of the Braille System of touch-reading.

In popular culture

- Enrique Gaspar y Rimbau's time travel novel El Anacronópete starts with a lecture in the exposition.

- Eoin Colfer's novel Airman begins with its protagonists (Conor Broekhart) birth at the exposition.

Artefacts

The Paris firm of Gruel and Engelmann was known for its deluxe bookbindings. The Book of Hours is a Gothic Revival example, the celebrated Paris jeweler Alexis Falize (1811–1898) has created a relief showing the Adoration of the Magi, surrounded by fantastic animals derived from the amusing, marginal decoration found in some medieval manuscripts. The filigree and granular work is of exceptional quality. Since the binding does not contain a book, it may have been produced solely for the firm's display at the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1878.

Souvenir ribbon from the exhibition

Souvenir ribbon from the exhibition Panorama of Paris

Panorama of Paris Binding for a Book of Hours

Binding for a Book of Hours Japanese incense container

Japanese incense container Simyan vase

Simyan vase Fountain made in 1877 shown at the exhibition

Fountain made in 1877 shown at the exhibition Japanese incense container

Japanese incense container Europe by Alexandre Schoenewerk

Europe by Alexandre Schoenewerk Asia by Alexandre Falguière

Asia by Alexandre Falguière Oceania by Mathurin Moreau

Oceania by Mathurin Moreau South America by Aimé Millet

South America by Aimé Millet Elephant by Emmanuel Fremiet

Elephant by Emmanuel Fremiet

Horse by Pierre Louis Rouillard

Horse by Pierre Louis Rouillard Bull in Parc Georges-Brassens by Isidore Bonheur

Bull in Parc Georges-Brassens by Isidore Bonheur

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ This includes six world expositions (in 1855, 1867, 1878, 1889, 1900 and 1937), two specialized expositions (in 1881 and 1925) and two colonial expositions (in 1907 and 1931).

References

- ↑ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 807.

- ↑ Koch, Georg (2015). "Charles-Marie Widor / Symphonie VI / op. 42/2" (PDF). Carus-Verlag. pp. VI–VIII. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ↑ David Oakes Woodbury (1949). A Measure for Greatness: A Short Biography of Edward Weston. McGraw-Hill. p. 83. Retrieved 2009-01-04.

- ↑ "Mouchot solar engine". hotairengines.org.

- ↑ Hipkins, Alfred James; Schlesinger, Kathleen (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ "My New York Consolidated Card Company (NYCC) Jokers".

- ↑ "New York Consolidated Card Company".

- ↑ Base Palissy: Statue : Amphitrite, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

Further reading

- Grapard, Ulla (2003). "Trading Bodies, Trade in Bodies: The 1878 Paris World Exhibition as Economic Discourse". In Zein-Elabdin, Eiman O.; Charusheela, S. (eds.). Postcolonialism meets Economics. Routledge. pp. 91–112. ISBN 0-415-28726-X.

External links

Exposition Universelle.

- Official website of the BIE

- L'Exposition universelle de 1878 illustrée : publication internationale autorisée par la Commission in Gallica, the digital library of the BnF.