| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

1,1-Dimethylhydrazine[1] | |

| Other names

Dimazine | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| 605261 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.287 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | dimazine |

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 1163 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

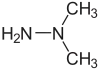

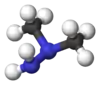

| H2NN(CH3)2 | |

| Appearance | Colorless liquid |

| Odor | Ammoniacal, fishy |

| Density | 791 kg m−3 (at 22 °C) |

| Melting point | −57 °C; −71 °F; 216 K |

| Boiling point | 64.0 °C; 147.1 °F; 337.1 K |

| Miscible[2] | |

| Vapor pressure | 13.7 kPa (at 20 °C) |

Refractive index (nD) |

1.4075 |

| Thermochemistry | |

Heat capacity (C) |

164.05 J K−1 mol−1 |

Std molar entropy (S⦵298) |

200.25 J K−1 mol−1 |

Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

48.3 kJ mol−1 |

Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) |

−1982.3 – −1975.1 kJ mol−1 |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards |

Carcinogen, spontaneously ignites on contact with oxidizers |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H225, H301, H314, H331, H350, H411 | |

| P210, P261, P273, P280, P301+P310 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | −10 °C (14 °F; 263 K) |

| 248 °C (478 °F; 521 K) | |

| Explosive limits | 2–95% |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose) |

|

LC50 (median concentration) |

|

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 0.5 ppm (1 mg/m3) [skin][2] |

REL (Recommended) |

Ca C 0.06 ppm (0.15 mg/m3) [2 hr][2] |

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

Ca [15 ppm][2] |

| Related compounds | |

Related compounds |

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine (UDMH; 1,1-dimethylhydrazine, heptyl or codenamed Geptil) is a chemical compound with the formula H2NN(CH3)2 that is used as a rocket propellant. It is a colorless liquid, with a sharp, fishy, ammonia-like smell typical for organic amines. Samples turn yellowish on exposure to air and absorb oxygen and carbon dioxide. It is miscible with water, ethanol, and kerosene. In concentration between 2.5% and 95% in air, its vapors are flammable. It is not sensitive to shock. Symmetrical dimethylhydrazine (1,2-dimethylhydrazine) is also known but is not as useful.[4] UDMH can be oxidized in air to form many different substances, including toxic ones.[5]

Production

UDMH is produced industrially by two routes.[4] Based on the Olin Raschig process, one method involves reaction of monochloramine with dimethylamine giving 1,1-dimethylhydrazinium chloride:

- (CH3)2NH + NH2Cl → (CH3)2NNH2 ⋅ HCl

In the presence of suitable catalysts, acetylhydrazine can be N-dimethylated using formaldehyde and hydrogen to give the N,N-dimethyl-N'-acetylhydrazine, which can subsequently be hydrolyzed:

- CH3C(O)NHNH2 + 2CH2O + 2H2 → CH3C(O)NHN(CH3)2 + 2H2O

- CH3C(O)NHN(CH3)2 + H2O → CH3COOH + H2NN(CH3)2

Uses

UDMH is often used in hypergolic rocket fuels as a bipropellant in combination with the oxidizer nitrogen tetroxide and less frequently with IRFNA (inhibited red fuming nitric acid) or liquid oxygen. UDMH is a derivative of hydrazine and is sometimes referred to as a hydrazine. As a fuel, it is described in specification MIL-PRF-25604 in the United States.[6]

UDMH is stable and can be kept loaded in rocket fuel systems for long periods, which makes it appealing for use in many liquid rocket engines, despite its cost. In some applications, such as the OMS in the Space Shuttle or maneuvering engines, monomethylhydrazine is used instead due to its slightly higher specific impulse. In some kerosene-fueled rockets, UDMH functions as a starter fuel to start combustion and warm the rocket engine prior to switching to kerosene.

UDMH has higher stability than hydrazine, especially at elevated temperatures, and can be used as its replacement or together in a mixture. UDMH is used in many European, Russian, Indian, and Chinese rocket designs. The Russian SS-11 Sego (aka 8K84) ICBM, SS-19 Stiletto (aka 15A30) ICBM, Proton, Kosmos-3M, R-29RMU2 Layner, R-36M, Rokot (based on 15A30) and the Chinese Long March 2F are the most notable users of UDMH (which is referred to as "heptyl" [codename from Soviet era] by Russian engineers[7]). The Titan, GSLV, and Delta rocket families use a mixture of 50% hydrazine and 50% UDMH, called Aerozine 50, in different stages.[8] There is speculation that it is the fuel used in the ballistic missiles that North Korea has developed and tested in 2017.[9]

Safety

Hydrazine and its methyl derivatives are toxic but LD50 values have not been reported.[10] It is a precursor to dimethylnitrosamine, which is carcinogenic.[11] According to scientific data, usage of UDMH in rockets at Baikonur Cosmodrome has had adverse effects on the environment and local population.[12]

See also

References

- ↑ "dimazine – Compound Summary". PubChem Compound. USA: National Center for Biotechnology Information. 26 March 2005. Identification. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0227". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ↑ "1,1-Dimethylhydrazine". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- 1 2 Schirmann, Jean-Pierre; Bourdauducq, Paul (2001). "Hydrazine". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a13_177. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ↑ Aleksey Milyushkin, Anastasia Karnaeva (2023). "Unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine transformation products: A review". Science of the Total Environment. 891: 164367. Bibcode:2023ScTEn.891p4367M. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.164367. PMID 37236454. S2CID 258899003.

- ↑ "PERFORMANCE SPECIFICATION PROPELLANT, uns-DIMETHYLHYDRAZINE (MIL-PRF-25604F)". ASSIST Database Quicksearch. 2014-03-11. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- ↑ "Following Russian rocket explosion, experts warn of 'major contamination'". 2 July 2013.

- ↑ Clark, John D. (1972). Ignition! An Informal History of Liquid Rocket Propellants. Rutgers University Press. p. 45. ISBN 0-8135-0725-1.

- ↑ Broad, William J.; Sanger, David E. (17 September 2017). "The Rare, Potent Fuel Powering North Korea's Weapons". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-07-06. Retrieved 2018-07-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Gangadhar Choudhary, Hugh Hansen (1998). "Human health perspective of environmental exposure to hydrazines: A review". Chemosphere. 37 (5): 801–843. Bibcode:1998Chmsp..37..801C. doi:10.1016/S0045-6535(98)00088-5. PMID 9717244.

- ↑ Abdrazak, P. Kh; Musa, K. Sh (21 June 2015). "The impact of the cosmodrome "Baikonur" on the environment and human health". International Journal of Biology and Chemistry. 8 (1): 26–29. doi:10.26577/2218-7979-2015-8-1-26-29. Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2016 – via ijbch.kaznu.kz.