| Zürich German | |

|---|---|

| Züritüütsch | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈtsyrityːtʃ] ⓘ |

| Native to | Canton of Zürich |

| Latin script | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | zuri1239 |

| Linguasphere | 52-ACB-fg[1] |

| IETF | gsw-u-sd-chzh[2][3] |

Zürich German (natively Züritüütsch [ˈtsyrityːtʃ] ⓘ; Standard German: Zürichdeutsch) is the High Alemannic dialect spoken in the Canton of Zürich, Switzerland. Its area covers most of the canton, with the exception of the parts north of the Thur and the Rhine, which belong to the areal of the northeastern (Schaffhausen and Thurgau) Swiss dialects.

Zürich German was traditionally divided into six sub-dialects, now increasingly homogenised owing to larger commuting distances:

- The dialect of the town of Zürich (Stadt-Mundart)

- The dialect spoken around Lake Zürich (See-Mundart)

- The dialect of the Knonauer Amt west of the Albis (Ämtler Mundart)

- The dialect of the area of Winterthur

- The dialect of the Zürcher Oberland around Lake Pfäffikon and the upper Tösstal valley

- The dialect of the Zürcher Unterland around Bülach and Dielsdorf

Like all Swiss German dialects, it is essentially a spoken language, whereas the written language is standard German. Likewise, there is no official orthography of the Zürich dialect. When it is written, it rarely follows the guidelines published by Eugen Dieth in his book Schwyzertütschi Dialäktschrift. Furthermore, Dieth's spelling uses a lot of diacritical marks not found on a normal keyboard. Young people often use Swiss German for personal messages, such as when texting with their mobile phones. As they do not have a standard way of writing they tend to blend Standard German spelling with Swiss German phrasing.

The Zürich dialect is generally perceived as fast spoken and less melodic than, for example, Bernese German. Characteristic of the city dialect is that it most easily adopts external influences. The second-generation Italian immigrants (secondi) have had a crucial influence, as has the English language through the media. The wave of Turkish and ex-Yugoslavian immigration of the 1990s is also leaving its imprint on the dialect of the city.

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Dorsal | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||

| Plosive | Lenis | b̥ | d̥ | ɡ̊ | ||

| Fortis | p | t | k | |||

| Affricate | pf | ts | tʃ | kx | ||

| Fricative | Lenis | v̥ | z̥ | ʒ̊ | ɣ̊ | h |

| Fortis | f | s | ʃ | (x) | ||

| Approximant | ʋ | l | j | |||

| Rhotic | r | |||||

- The distinction between the lenis /b̥, d̥, ɡ̊, v̥, z̥, ʒ̊, ɣ̊/ on the one hand and the fortis /p, t, k, f, s, ʃ, x/ on the other is not one of voice but length, with the fortis obstruents being the longer ones. A difference in tenseness is also claimed by some authors, with the fortes being more tense. /h/ does not participate in this distinction and neither do the affricates. The contrast occurs in all contexts (word-initial, word-internal and word-final) in the case of plosives. In the case of fricatives, it occurs only in the word-internal and word-final positions. Word-initially, only lenes appear, except in consonant clusters where fortes (especially /ʃ/) appear through assimilation. Postvocalic /ʒ̊/ tends to appear only after long vowels. /k/ and /kx/ occur mainly in the word-internal and word-final contexts. Word-initially, /ɣ̊/ tends to appear instead. In monosyllabic nouns, short vowels tend to be followed by fortes. /x/ appears only after short vowels.[5] See fortis and lenis for more details. In the table above, /h/ is classified as lenis on the basis of its length and distribution (it occurs in the word-initial and word-internal positions).

- /p/ and /t/ are aspirated in borrowings from Standard German, e.g. Pack [pʰɒkx] 'parcel'. In other contexts, they are unaspirated, as is /k/. In borrowings with an aspirated [kʰ], it is nativized to an affricate /kx/, as in Kampf /kxɒmpf/ 'fight' (cf. Northern Standard German [kʰampf]).[6]

- Intervocalic nasals are short traditional Zürich German. However, younger speakers tend to realize at least the bilabial /m/ and the velar /ŋ/ as long in this position, possibly under the influence of other dialects. This is particularly common before /ər/ and /əl/, as in Hammer [ˈhɒmːər] 'hammer' and lenger [ˈleŋːər] 'longer'. This may also apply to /l/, as in Müller [ˈmylːər] 'miller'.[7]

- /ɣ̊, x/ vary between velar [ɣ̊, x] and uvular [ʁ̥, χ] in all contexts, including when in contact with front vowels. The distinction between the Ich-Laut and the Ach-Laut found in Standard German does not exist in the Zürich dialect. Chemii /ɣ̊eˈmiː/ 'chemistry' is thus pronounced [ɣ̊eˈmiː] or [ʁ̥eˈmiː] but never [ʝ̊eˈmiː], with a voiceless palatal fricative [ʝ̊] found in Northern and Swiss Standard German [çeˈmiː] (with ⟨ç⟩ being a difference in transcription, not in pronunciation). That sound does not exist in Zürich German. Similarly, /kx/ can also be realized as uvular [qχ], as in ticke [ˈtiqχə] 'thick' (infl.).[8][9]

- The reflex of the Middle High German /w/ is an approximant /ʋ/ and not a voiced fricative /v/, unlike in Northern Standard German. The voiced labiodental fricative does not occur in Zürich German.[4]

- The traditional pronunciation of the rhotic /r/ is an alveolar tap [ɾ], but the uvular variants [ʀ] (a uvular trill), [ʁ] (a voiced uvular fricative), [ʁ̞] (a uvular approximant) and [ʁ̥] (a voiceless lenis uvular fricative) are now more frequent. The last one overlaps phonetically with the uvular realization of /ɣ̊/. Speakers can switch between alveolar and uvular articulations, as shown in Fleischer & Schmid's transcription of The North Wind and the Sun. This is very similar to the situation in many dialects of Dutch. R-vocalization does not occur; töörfe /ˈtœːrfə/ 'to be allowed to' is thus never pronounced [ˈtœːɐ̯fə], only [ˈtœːʁfə] etc.[8][10] Elsewhere in the article, the rhotic is written with ⟨r⟩ regardless of its precise quality.

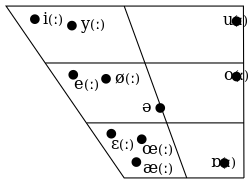

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | |||||||

| short | long | short | long | short | short | long | ||

| Close | i | iː | y | yː | u | uː | ||

| Close-mid | e | eː | ø | øː | (ə) | o | oː | |

| Open-mid | (ɛ) | ɛː | (œ) | œː | ||||

| Open | æ | æː | ɒ | ɒː | ||||

| Diphthongs | closing | (ui) ei oi æi ou æu | ||||||

| centering | iə yə uə | |||||||

- Traditional Zürich German features an additional, near-close series /ɪ, ɪː, ʏ, ʏː, ʊ, ʊː/, which seems about to disappear. Vowels from these series can form minimal pairs with the close series, as exemplified by the minimal pair tüür /tʏːr/ 'dry' vs. tüür /tyːr/ 'expensive'.[12]

- The short /e/ and /ɛ/ were originally in complementary distribution, with the latter occurring before /r/ and /x/ and the former elsewhere. A phonemic split has occurred through analogy and borrowing, with /ɛ/ now occurring in places where originally only /e/ could appear.[12]

- The long /ɛː/ can easily form minimal pairs with /eː/, as in the minimal pair hèèr /hɛːr/ 'from' vs. Heer /heːr/ 'army'.[12]

- The short /œ/ has a marginal status. In native words, it can only occur before /r/ and /x/. The word Hördöpfel /ˈhœrd̥ˌøpfəl/ 'potato' has a common alternative Herdöpfel /ˈhɛrd̥ˌøpfəl/, with an unrounded /ɛ/ (cf. Austrian Standard German Erdapfel [ˈeːɐ̯d̥ˌapfl̩]). In addition, /œ/ occurs in loanwords as a substitute for English /ʌ/, as in Bluff /b̥lœf/ 'bluff' (n).[12]

- /ə/ appears only in unstressed syllables. In native words, only it and /i/ can appear in unstressed syllables, as exemplified by the minimal pair schweche /ˈʒ̊ʋɛxə/ 'to weaken' vs. Schwechi /ˈʒ̊ʋɛxi/ 'weakness'. In borrowings, other vowels can also appear in the unstressed position, e.g. Bambus /ˈb̥ɒmb̥us/ 'bamboo'.[12]

- The open front /æ(ː)/ are phonetically near-front [æ̠(ː)].[7]

- The open back /ɒ(ː)/ have a variable rounding and may be realized as unrounded [ɑ(ː)].[13]

- All diphthongs are falling, with the first element being more prominent: [ui̯, ei̯, oi̯, ou̯, æu̯, iə̯, yə̯, uə̯].[13]

- /ui/ is marginal and occurs only in exclamations such as pfui /pfui/ 'ugh!'.[13]

- Originally, two diphthongs with a rounded mid front first element were distinguished. Those were /øi/ and /œi/ (phonetically falling [øi̯, œi̯], as the rest), distinguished phonemically as in the near-minimal pair nöi /nøi/ 'new' vs. Höi /hœi/ 'hay'. They have since merged into one diphthong /oi/.[13]

Sample

The sample text is a reading of the first sentence of The North Wind and the Sun. It is a recording of a 67-year old male from the town of Meilen, about 15 kilometers from the city of Zürich.[14]

Phonemic transcription

/əˈmɒːl hænd̥ d̥ə ˈb̥iːz̥ˌʋind̥ und̥ d̥ ˈz̥unə ˈkʃtritə | ʋɛːr v̥o ˈb̥æid̥nə d̥ɒz̥ æxt d̥ə ˈʃtɛrɣ̊ər z̥eiɡ̊/[15]

Phonetic transcription

[əˈmɒːl hæn‿tə ˈb̥iːz̥ˌʋind̥ un‿ˈtsunə ˈkʃtritə | ʋɛːr v̥o ˈb̥æiʔnə d̥ɒz̥ æx‿tə ˈʃtɛrɣ̊ər z̥eiɡ̊][15]

Orthographic version

Emaal händ de Biiswind und d Sune gschtritte, wèèr vo bäidne das ächt de schtèrcher seig.[15]

Further reading

- Dieth, Eugen (1986). Schwyzertütschi Dialäktschrift (in German). Aarau: Sauerländer. ISBN 978-3-7941-2832-7. (proposed orthography)

- Salzmann, Martin: Resumptive Prolepsis: A study in indirect A'-dependencies. Utrecht: LOT, 2006 (=LOT Dissertation Series 136). Chapter 4: Resumptives in Zurich German relative clauses, online.

- Weber, Albert: Zürichdeutsche Grammatik. Ein Wegweiser zur guten Mundart. With the participation of Eugen Dieth. Zürich (=und Wörterbücher des Schweizerdeutschen in allgemeinverständlicher Darstellung. Bd. I). (in German)

- Weber, Albert and Bächtold, Jacques M.. Zürichdeutsches Wörterbuch. Zürich (=Grammatiken und Wörterbücher des Schweizerdeutschen in allgemeinverständlicher Darstellung. Bd. III).

- Egli-Wildi, Renate (2007). Züritüütsch verstaa, Züritüütsch rede (108 pages + 2 CDs) (in German). Küsnacht: Society for Swiss German, Zürich Section. ISBN 978-3-033-01382-7.

- Fleischer, Jürg; Schmid, Stephan (2006). "Zurich German". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 36 (2): 243–253. doi:10.1017/S0025100306002441.

- Gallmann, Heinz (2009). Zürichdeutsches Wörterbuch [Zurich German Dictionary] (in German). Zürich: NZZ Libro. ISBN 978-3-03823-555-2.

- Krech, Eva Maria; Stock, Eberhard; Hirschfeld, Ursula; Anders, Lutz-Christian (2009), Deutsches Aussprachewörterbuch, Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-018202-6

- Sebregts, Koen (2014), The Sociophonetics and Phonology of Dutch r (PDF), Utrecht: LOT, ISBN 978-94-6093-161-1

References

- ↑ "Züri-Tüütsch". Linguasphere Observatory. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ↑ "Territory Subdivisions: Switzerland". Common Locale Data Repository. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ↑ "Swiss German". IANA language subtag registry. 8 March 2006. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- 1 2 Fleischer & Schmid (2006), p. 244.

- ↑ Fleischer & Schmid (2006), pp. 244–245, 247–248.

- ↑ Fleischer & Schmid (2006), pp. 244, 246.

- 1 2 Fleischer & Schmid (2006), p. 246.

- 1 2 Fleischer & Schmid (2006), pp. 244, 251.

- ↑ Krech et al. (2009), pp. 266, 273.

- ↑ Sebregts (2014), pp. 86–124.

- ↑ Fleischer & Schmid (2006), pp. 246–248.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fleischer & Schmid (2006), p. 247.

- 1 2 3 4 Fleischer & Schmid (2006), p. 248.

- ↑ Fleischer & Schmid (2006), p. 243.

- 1 2 3 Fleischer & Schmid (2006), p. 251.