Zengid State الدولة الزنكية | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1127–1250 | |||||||||||||||

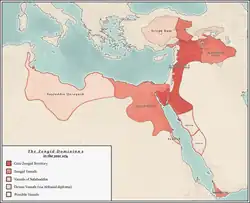

The Zengid state in the mid 12th century | |||||||||||||||

| Status | Atabegate (vassal of the Seljuk Empire), Emirate | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Damascus | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Oghuz Turkic Arabic (numismatics)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam Shia Islam | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Emirate | ||||||||||||||

| Emir | |||||||||||||||

• 1127–1146 | Imad ad-Din Zengi (first) | ||||||||||||||

• 1241–1250 | Mahmud Al-Malik Al-Zahir (last reported) | ||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||

• Established | 1127 | ||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1250 | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Dinar | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

The Zengid or Zangid dynasty (Arabic: الدولة الزنكية romanized: al-Dawla al-Zinkia) was a Sunni Muslim dynasty of Turkoman origin,[2] which ruled parts of the Levant and Upper Mesopotamia on behalf of the Seljuk Empire and eventually seized control of Egypt in 1169.[3][4] In 1174 the Zengid state extended from Tripoli to Hamadan and from Yemen to Sivas.[5][6] The dynasty was founded by Imad ad-Din Zengi.

History

Zengi, son of Aq Sunqur al-Hajib, Seljuk Governor of Aleppo, became the Seljuk atabeg of Mosul in 1127.[7] He quickly became the chief Turkic potentate in Northern Syria and Iraq, taking Aleppo from the squabbling Artuqids in 1128 and capturing the County of Edessa from the Crusaders after the siege of Edessa in 1144. This latter feat made Zengi a hero in the Muslim world, but he was assassinated by a slave two years later, in 1146.[8]

On Zengi's death, his territories were divided, with Mosul and his lands in Iraq going to his eldest son Saif ad-Din Ghazi I, and Aleppo and Edessa falling to his second son, Nur ad-Din, atabeg of Aleppo.

Conflict with the Crusaders

Nur ad-Din proved to be as competent as his father. In 1146 he defeated the Crusaders at the Siege of Edessa. In 1149, he defeated Raymond of Poitiers, Prince of Antioch, at the battle of Inab, and the next year conquered the remnants of the County of Edessa west of the Euphrates.[9] In 1154, he capped off these successes by his capture of Damascus from the Burid dynasty that ruled it.[10]

Now ruling from Damascus, Nur ad-Din's success continued. Another Prince of Antioch, Raynald of Châtillon was captured, and the territories of the Principality of Antioch were greatly reduced.

Conquests

In the 1160s, Nur ad-Din's attention was mostly held by a competition with the King of Jerusalem, Amalric of Jerusalem, for control of the Fatimid Caliphate in Egypt. From 1163 to 1169, Shirkuh, a military commander in the service of the Zengid dynasty, took part in a series of campaigns against Fatimid Egypt. In 1169, he lured the vizier into an ambush and killed him after which he seized Egypt in the name of his master Nur ad-Din therefore bringing Egypt under formal Zengid dominion.[4][3]

During the reign of Nur al-Din (1146-1174), Tripoli, Yemen and the Hejaz were added to the state of the Zengids.[5] Nur ad-Din also took control of Anatolian lands up to Sivas. His state extended from Tripoli to Hamadan and from Yemen to Sivas.[6]

Shirkuh's nephew Saladin was appointed vizier by the last Fatimid caliph al-Adid and Governor of Egypt, in 1169. Al-Adid died in 1171, and Saladin took advantage of this power vacuum, effectively taking control of the country. Upon seizing power, he switched Egypt's allegiance to the Baghdad-based Abbasid Caliphate which adhered to Sunni Islam, rather than traditional Fatimid Shia practice.

._'Izz_al-Din_Mas'ud_I._1180-1193_CE._Mosul_mint._Dated_1189-90_CE.jpg.webp)

Nur ad-Din was preparing to invade the Kingdom of Jerusalem when he unexpectedly died in 1174. His son and successor As-Salih Ismail al-Malik was only a child, and was forced to flee to Aleppo, which he ruled until 1181, when he died of illness and was replaced by his cousin Imad al-Din Zengi II.

Decline (1183-1250)

Saladin conquered Aleppo in 1183, ending Zengid rule in Syria. Saladin launched his last offensive against Mosul in late 1185, hoping for an easy victory over the presumably demoralized Zengid Emir of Mosul Mas'ud, but failed due to the city's unexpectedly stiff resistance and a serious illness which caused Saladin to withdraw to Harran. Upon Abbasid encouragement, Saladin and Mas'ud negotiated a treaty in March 1186 that left the Zengids in control of Mosul, but under the obligation to supply the Ayyubids with military support when requested, thereby accepting suzerainty.[13]

Zengid princes continued to rule in Northern Iraq as Emirs of Mosul well into the 13th century, ruling Mosul and Sinjar until 1234. Mosul and Sinjar were taken over by Badr al-Din Lu'lu' in 1234, who ruled until his death 1259. Northern Iraq (al-Jazira region), continued to be under Zengid rule until 1250, with its last Emir Mahmud al-Malik al-Zahir (1241–1250, son of Mu'izz al-Din Mahmud). In 1250, al-Jazira fell under the domination of An-Nasir Yusuf, the Ayyubid emir of Aleppo, marking the end of Zengil rule. The next period would be marked by the arrival of the Mongols: in 1262 Mosul was sacked by the Mongols of Hulagu, following a siege of almost a year.

Metalwork

In the 13th century, Mosul had a flourishing industry making luxury brass items that were ornately inlaid with silver.[16]: 283–6 Many of these items survive today; in fact, of all medieval Islamic artifacts, Mosul brasswork has the most epigraphic inscriptions.[17]: 12 However, the only reference to this industry in contemporary sources is the account of Ibn Sa'id, an Andalusian geographer who traveled through the region around 1250.[16]: 283–4 He wrote that "there are many crafts in the city, especially inlaid brass vessels which are exported (and presented) to rulers".[16]: 284 These were expensive items that only the wealthiest could afford, and it wasn't until the early 1200s that Mosul had the demand for large-scale production of them.[16]: 285 Mosul was then a wealthy, prosperous capital city, first for the Zengids and then for Badr al-Din Lu'lu'.[16]: 285

The origins of Mosul's inlaid brasswork industry are uncertain.[17]: 52 The city had an iron industry in the late 10th century, when al-Muqaddasi recorded that it exported iron and iron goods like buckets, knives and chains.[17]: 52 However, no surviving metal objects from Mosul are known before the early 13th century.[17]: 52 Inlaid metalworking in the Islamic world was first developed in Khurasan in the 12th century by silversmiths facing a shortage of silver.[17]: 52–3 By the mid-12th century, Herat in particular had gained a reputation for its high-quality inlaid metalwork.[17]: 53 The practice of inlaying "required relatively few tools" and the technique spread westward, perhaps by Khurasani artisans moving to other cities.[17]: 53

By the turn of the 13th century, the silver-inlaid-brass technique had reached Mosul.[17]: 53 A pair of engraved brass flabella found in Egypt and possibly made in Mosul are dated by a Syriac inscription to the year 1202, which would make them the earliest known Mosul brasses with a definite date (although they are not inlaid with anything).[17]: 49–50 One extant item may be even older: an inlaid ewer by the master craftsman Ibrahim ibn Mawaliya is of an unknown date, but D.S. Rice estimated that it was made around 1200.[17]: 53 Production of inlaid brasswork in Mosul may have already begun before the turn of the century.[17]: 53–4

The body of Mosul metalwork significantly expands in the 1220s - several signed and dated items are known from this decade, which according to Julian Raby "probably reflects the craft's growing status and production."[17]: 54 In the two decades from roughly 1220 to 1240, the Mosul brass industry saw "rapid innovations in technique, decoration, and composition".[17]: 54 Artisans were inspired by miniature paintings produced in the Mosul area.[17]: 54

Mosul seems to have become predominant among Muslim centers of metalwork in the early 13th century.[17]: 53 Evidence is partial and indirect - relatively few objects which directly state where they were made exist, and in the rest of cases it depends on nisbahs.[17]: 53 However, al-Mawsili is by far the most common nisbah; only two others are attested: al-Is'irdi (referring to someone from Siirt) and al-Baghdadi.[17]: 53 There are, however, some scientific instruments inlaid with silver that were made in Syria during this period, with the earliest being 1222/3 (619 AH).[17]: 53

Instability after the death of Badr al-Din Lu'lu' in 1259, and especially the Mongol siege and capture of Mosul in July 1262, probably caused a decline in Mosul's metalworking industry.[17]: 54 There is a relative lack of known metalwork from the Jazira in the late 1200s; meanwhile, an abundance of metalwork from Mamluk Syria and Egypt is attested from this same period.[17]: 54 This doesn't necessarily mean that production in Mosul ended, though, and some extant objects from this period may have been made in Mosul.[17]: 54–5

Literature

The manuscript Kitâb al-Diryâq (Arabic: كتاب الدرياق, romanized: Kitāb al-diryāq, "The Book of Theriac"), or Book of anditodes of pseudo-Galen, is a medieval manuscript alledgedly based on the writings of Galen ("pseudo-Galen"). It describes the use of Theriac, an ancient medicinal compound initially used as a cure for the bites of poisonous snakes. Two editions are extant, adorned with beautiful miniatures revealing of the social context at the time of their publication.[18] The earliest manuscript was published in 1198-1199 CE in Mosul or the Jazira region, and is now in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (MS. Arabe 2964).[18][19]

.jpg.webp) Kitâb al-Diryâq, 1198-1199, folio 24. Royal court detail, ruler in Turkic dress.[20]

Kitâb al-Diryâq, 1198-1199, folio 24. Royal court detail, ruler in Turkic dress.[20].jpg.webp) Kitâb al-Diryâq, 1198-1199, folio 43. Moon divinity

Kitâb al-Diryâq, 1198-1199, folio 43. Moon divinity.jpg.webp) Kitâb al-Diryâq, 1198-1199, folio 44. Moon divinity

Kitâb al-Diryâq, 1198-1199, folio 44. Moon divinity.jpg.webp) Andromachus the Elder on horseback, questionning a patient who has received a snake bite. Kitâb al-Diryâq, 1198-1199.[18]

Andromachus the Elder on horseback, questionning a patient who has received a snake bite. Kitâb al-Diryâq, 1198-1199.[18]

Zengid rulers

Zengid Atabegs and Emirs of Mosul

- Zengi, 1127–1146

- Sayf al-Din Ghazi I, son of Zengi, 1146–1149

- Qutb al-Din Mawdud, son of Zengi, 1149–1170

- Sayf al-Din Ghazi II, son of Qutb al-Din Mawdud, 1170–1180

- Izz al-Din Mas'ud, son of Qutb al-Din Mawdud, 1180–1193

- Nur al-Din Arslan Shah I, son of Izz al-Din Mas'ud, 1193–1211

- Izz al-Din Mas'ud II, son of Nur al-Din Arslan Shah I, 1211–1218

- Nur al-Din Arslan Shah II, son of Izz al-Din Mas'ud II, 1218–1219

- Nasir ad-Din Mahmud, son of Izz al-Din Mas'ud, 1219–1234.

Mosul was taken over by Badr al-Din Lu'lu', atabeg to Nasir ad-Din Mahmud, whom he murdered in 1234.

Zengid Emirs of Aleppo

- Zengi, 1128–1146

- Nur al-Din, son of Zengi, 1146–1174

- As-Salih Ismail al-Malik, son of Nur al-Din, 1174–1182

- Imad al-Din Zengi II,1182

Aleppo was conquered by Saladin in 1183 and ruled by Ayyubids until 1260.

Zengid Emirs of Damascus

- Nur al-Din, son of Zengi, 1154–1174

- As-Salih Ismail al-Malik, son of Nur al-Din, 1174.

Damascus was conquered by Saladin in 1174 and ruled by Ayyubids until 1260.

Zengid Emirs of Sinjar

- Imad al-Din Zengi II, son of Qutb al-Din Mawdud, 1171–1197

- Qutb ad-Din Muhammad, son of Zengi II, 1197–1219

- Imad al-Din Shahanshah, son of Qutb ad-Din Muhammad, 1219–1220

- Jalal al-Din Mahmud (co-ruler), son of Qutb ad-Din Muhammad, 1219–1220

- Fath al-Din Umar (co-ruler), son of Qutb ad-Din Muhammad, 1219–1220.

Sinjar was taken by the Ayyubids in 1220 and ruled by al-Ashraf Musa, Ayyubid emir of Diyar Bakr. It later came under the control of Badr al-Din Lu'lu', ruler of Mosul beginning in 1234.

Zengid Emirs of al-Jazira (in Northern Iraq)

- Mu'izz al-Din Sanjar Shah, son of Sayf al-Din Ghazi II, 1180–1208

- Mu'izz al-Din Mahmud, son of Mu'izz al-Din Sanjar Shah, 1208–1241

- Mahmud al-Malik al-Zahir, son of Mu'izz al-Din Mahmud, 1241–1250.

In 1250, al-Jazira fell under the domination of an-Nasir Yusuf, Ayyubid emir of Aleppo.

Coin of Nasir ad-Din Mahmud, mint of Mosul, depicting a female with two winged victories, 1223. British Museum.

Coin of Nasir ad-Din Mahmud, mint of Mosul, depicting a female with two winged victories, 1223. British Museum..jpg.webp) Coin of Qutb al-Din Muhammad bin Zengi, Zengid Atabeg of Sinjar (1197-1219). Sinjar mint. Dated AH 600 (AD 1203–1204).

Coin of Qutb al-Din Muhammad bin Zengi, Zengid Atabeg of Sinjar (1197-1219). Sinjar mint. Dated AH 600 (AD 1203–1204)..jpg.webp) Coin of Qutb al-Din Muhammad bin Zengi, Zengid Atabeg of Sinjar (1197-1219). Sinjar mint. Dated AH 607 (AD 1210–1201).

Coin of Qutb al-Din Muhammad bin Zengi, Zengid Atabeg of Sinjar (1197-1219). Sinjar mint. Dated AH 607 (AD 1210–1201).._Mu'izz_al-Din_Sanjar_Shah._1180-1208_CE.jpg.webp) Zangids (al-Jazira). Mu'izz al-Din Sanjar Shah (AD 1180-1208), dated 1188/9

Zangids (al-Jazira). Mu'izz al-Din Sanjar Shah (AD 1180-1208), dated 1188/9

See also

References

- ↑ Canby et al. 2016, p. 69.

- ↑ Bosworth 1996, p. 191.

- 1 2 Legitimising the Conquest of Egypt: The Frankish Campaign of 1163 Revisited. Eric Böhme. The Expansion of the Faith. Volume 14. January 1, 2022. Pages 269 - 280.

- 1 2 Souad, Merah, and Tahraoui Ramdane. 2018. “INSTITUTIONALIZING EDUCATION AND THE CULTURE OF LEARNING IN MEDIEVAL ISLAM: THE AYYŪBIDS (569/966 AH) (1174/1263 AD) LEARNING PRACTICES IN EGYPT AS A CASE STUDY”. Al-Shajarah: Journal of the International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilization (ISTAC), January, 245-75.

- 1 2 Gençtürk, Ç. "SELAHADDİN EYYUBİ VE NUREDDİN MAHMUD ARASINDAKİ MÜNASEBETLER". Ankara Uluslararası Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi 1 (2018 ): 51-61

- 1 2 EYYÛBÎLER. İçindekiler Tablosu. Prof. Dr. Ramazan ŞEŞEN. Mimar Sinan Üniversitesi.

- ↑ Ayalon 1999, p. 166.

- ↑ Irwin 1999, p. 227.

- ↑ Hunyadi & Laszlovszky 2001, p. 28.

- ↑ Asbridge 2012, p. 1153.

- ↑ "Blacas ewer British Museum". www.britishmuseum.org.

- ↑ Whelan Type II, 181-2; S&S Type 63.1; Album 1863.2

- ↑ Humphreys 1991, p. 781

- ↑ "`Umar ibn al-Hajji Jaldak Ewer with Inscription, Horsemen, and Vegetal Decoration". The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ↑ "Blacas ewer British Museum". www.britishmuseum.org.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rice, D.S. (1957). "Inlaid Brasses from the Workshop of Aḥmad al-Dhakī al-Mawṣilī". Ars Orientalis. 2: 283–326. JSTOR 4629040. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Raby, Julian (2012). "The Principle of Parsimony and the Problem of the 'Mosul School of Metalwork'". In Porter, Venetia; Rosser-Owen, Mariam (eds.). Metalwork and Material Culture in the Islamic World (PDF). Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 11–85. ISBN 978-0-85773-343-6. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- 1 2 3 Pancaroǧlu, Oya (2001). "Socializing Medicine: Illustrations of the Kitāb al-diryāq". Muqarnas. 18: 155–172. doi:10.2307/1523306. ISSN 0732-2992.

- ↑ Snelders, Bas (2010). Identity and Christian-Muslim Interaction: Medieval Art of the Syrian Orthodox from the Mosul Area. Peeters. pp. Extract. ISBN 978-90-429-2386-7.

Mosul appears to have been one of the main centres of illustrated manuscript production in the Middle East during the late twelfth and thirteenth centuries,252 alongside other major cities such as Baghdad, Damascus, and Cairo. A volume of al-Sufi's Kitab Suwar al-Kawakib alThabita ('Treatise on the Constellations'), copied by a certain Farah ibn cAbd Allah alHabashi, was produced in Mosul in 1233. Manuscripts ascribed to the city, or to the Jazira more broadly, include two copies of the Kitab al-Diryaq ('Book of the Theriac', usually called 'Book of Antidotes'), a medical treatise on antidotes used as a remedy against snake venom. Badr al-Din Lu'lu', who is known to have commissioned several literary texts, may also have been actively engaged in sponsoring manuscript illuminations. It is commonly assumed that an originally 20-volume set of the Kitab al-Aghani ('Book of Songs') was made for Lu'lu' in the period between 1217 and 1219. Some of the frontispieces depict a ruler wearing an armband that is inscribed with his name.

- ↑ Shahbazi, Shapur (30 August 2020). "CLOTHING". Encyclopaedia Iranica Online. Brill.

That these patterns do not merely represent ceramic conventions is clear from the rendering of garments in fragmentary wall paintings and in illustrations from the copy of Varqa wa Golšāh already mentioned, as well as in frontispieces to the volumes of Abu'l-Faraj Eṣfahānī's Ketāb al-aḡānī dated 614-16/1217-19 and to two copies of Ketāb al-deryāq (Book of antidotes) by Pseudo-Galen, dated 596/1199 and ascribed to the second quarter of the 7th/13th century respectively (Survey of Persian Art V, pl. 554A-B; Ateş, pls. 1/3, 6/16, 18; D. S. Rice, 1953, figs. 14-19; Ettinghausen, 1962, pp. 65, 85, 91). The last three manuscripts, all of them attributed to northern Mesopotamia, show that the stiff coat with diagonal closing and arm bands was also worn in that region from the end of the 6th/12th century.

Sources

- Asbridge, Thomas (2012). The Crusades: The War for the Holy Land. Simon & Schuster.

- Ayalon, David (1999). Eunuchs, Caliphs and Sultans: A Study in Power Relationships. Hebrew University Magnes Press.

- Bosworth, C.E. (1996). The New Islamic Dynasties: A Chronological and Genealogical Manual. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Canby, Sheila R.; Beyazit, Deniz; Rugiadi, Martina; Peacock, Andrew C. S. (2016). Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Humphreys, R.S. (1991). "Masūd b. Mawdūd b. Zangī". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume VI: Mahk–Mid (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 780–782. ISBN 978-90-04-08112-3.

- Hunyadi, Zsolt; Laszlovszky, József (2001). The Crusades and the Military Orders. Central European University.

- Irwin, Robert (1999). "Islam and the Crusades 1096-1699". In Riley-Smith, Jonathan (ed.). The Oxford History of the Crusades. Oxford University Press.

- Stevenson, William Barron (1907). The Crusaders in the East. Cambridge University Press.

- Taef El-Azharii (2006). Zengi and the Muslim Response to the Crusades, Routledge, Abington, UK.