A Yūpa (यूप), or Yūpastambha, was a Vedic sacrificial pillar used in Ancient India.[1] It is one of the most important elements of the Vedic rituals for animal sacrifice.[2]

The execution of a victim (generally an animal), who was tied at the yūpa, was meant to bring prosperity to everyone.[1][2]

Most yūpa, and all from the Vedic period, were in wood, and have not survived. The few stone survivals seem to be a later type of memorial using the form of the wooden originals. The Isapur Yupa, the most complete, replicates in stone the rope used to tether the animal. The topmost section is missing; texts describe a "wheel-like headpiece made of perishable material", representing the sun, but the appearance of that is rather unclear from the Gupta period coins that are the best other visual evidence.[3]

Isapur Yūpa

The Isapur Yūpa, now in the Mathura Museum, was found at Isapur (27°30′41″N 77°41′21″E / 27.5115°N 77.6893°E) in the vicinity of Mathura, and has an inscription in the name of the third century CE Kushan ruler Vāsishka, and mentions the erection of the Yūpa pillar for a sacrificial session.[4][5]

Yūpa in coinage

During the Gupta Empire period, the Ashvamedha scene of a horse tied to a yūpa sacrificial post appears on the coinage of Samudragupta. On the reverse, the queen is holding a chowrie for the fanning of the horse and a needle-like pointed instrument, with legend "One powerful enough to perform the Ashvamedha sacrifice".[7][8]

.jpg.webp) Samudragupta coin with horse standing in front of a yūpa sacrificial post, with legend "The King of Kings, who had performed the Ashvamedha sacrifice, wins heaven after conquering the earth".[7][8]

Samudragupta coin with horse standing in front of a yūpa sacrificial post, with legend "The King of Kings, who had performed the Ashvamedha sacrifice, wins heaven after conquering the earth".[7][8].jpg.webp)

Another version of the Ashvamedha scene. Coinage of Samudragutpa.

Another version of the Ashvamedha scene. Coinage of Samudragutpa.

Yūpa inscription in Indonesia

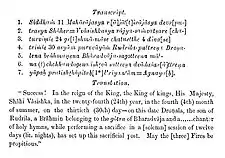

The oldest known Sanskrit inscriptions in the Nusantara are those on seven stone pillars, or Yūpa ("sacrificial posts"), found in the eastern part of Borneo, in the historical area of Kutai, East Kalimantan province.[9] They were written by Brahmins using the early Pallava script, in the Sanskrit language, to commemorate sacrifices held by a generous mighty king called Mulavarman who ruled the Kutai Martadipura Kingdom, the first Hindu kingdom in present Indonesia. Based on palaeographical grounds, they have been dated to the second half of the 4th century CE. They attest to the emergence of an Indianized state in the Indonesian archipelago prior to 400 CE.[10]

In addition to Mulavarman, the reigning king, the inscriptions mention the names of his father Aswawarman and his grandfather Kudungga (the founder of the Kutai Martadipura Kingdom). Aswawarman is the first of the line to bear a Sanskrit name in the Yupa which indicates that he was probably the first to adhere to Hinduism.[10]

.jpg.webp) Mulavarman inscription on a yūpa, 5th century CE

Mulavarman inscription on a yūpa, 5th century CE.jpg.webp) Mulavarman inscription on a yūpa, 5th century CE

Mulavarman inscription on a yūpa, 5th century CE The word "Yūpo" in Brahmi in a Mulavarman Inscription, Muara Kaman, Kalimantan, 5th century CE

The word "Yūpo" in Brahmi in a Mulavarman Inscription, Muara Kaman, Kalimantan, 5th century CE

Text

The four Yupa inscriptions founded are classified as "Muarakaman"s and has been translated by language experts as follows:

|

Muarakaman I[11]

|

Muarakaman II[12]

|

Muarakaman III[12]

|

Muarakaman IV[13]

|

Translation

Translation according to the Indonesia University of Education:[14]

|

Muarakaman I |

Muarakaman II |

Muarakaman III |

Muarakaman IV |

The Yupas are now kept in the National Museum of Indonesia in Jakarta.

References

- 1 2 Bonnefoy, Yves (1993). Asian Mythologies. University of Chicago Press. pp. 37–39. ISBN 978-0-226-06456-7.

- 1 2 SAHOO, P. C. (1994). "On the Yṻpa in the Brāhmaṇa Texts". Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute. 54/55: 175–183. ISSN 0045-9801. JSTOR 42930469.

- ↑ Irwin, John, "The Heliodorus Pillar: A Fresh Appraisal", p. 8, AARP, Art and Archaeology Research Papers, December, 1974, Internet archive, (also published in Purātattva, 8, 1975-1976, pp. 166-178)

- ↑ Catalogue Of The Archaeological Museum At Mathura. 1910. p. 189.

- ↑ Rosenfield, John M. (1967). The Dynastic Arts of the Kushans. University of California Press. p. 57.

- ↑ Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. pp. 431–433. ISBN 978-81-317-1677-9.

- 1 2 3 Houben, Jan E. M.; Kooij, Karel Rijk van (1999). Violence Denied: Violence, Non-Violence and the Rationalization of Violence in South Asian Cultural History. BRILL. p. 128. ISBN 978-90-04-11344-2.

- 1 2 3 Ganguly, Dilip Kumar (1984). History and Historians in Ancient India. Abhinav Publications. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-391-03250-7.

- ↑ Kulke, Hermann (1998). A History of India. p. 145.

- 1 2 S. Supomo, "Chapter 15. Indic Transformation: The Sanskritization of Jawa and the Javanization of the Bharata" in Peter S. Bellwood, James J. Fox, Darrell T. Tryon (eds.), The Austronesians: Historical and Comparative Perspectives, Australian National University, 1995

- ↑ R.M. Poerbatjaraka, Riwayat Indonesia, I, 1952, hal. 9.

- 1 2 R. M. Poerbatjaraka, Ibid., hal. 10.

- ↑ R. M. Poerbatjaraka, Ibid., hal. 11.

- ↑ Sumantri, Yeni Kurniawati. Rangkuman Materi Perkuliahan: Sejarah Indonesia Kuno. Fakultas Pendidikan Ilmu Pengetahuan Sosial, Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia.

- ↑ Note: archaeologists and historical experts has stated that "Waprakeswara" referred to a field dedicated to worship the Lord Shiva