| Yao 堯 | |

|---|---|

Chinese Emperor Yao | |

| Reign | 99 years[1] |

| Predecessor | Emperor Zhi |

| Successor | Emperor Shun |

| Born | Gaoyou, Jiangsu or Tianchang, Anhui |

| Spouse | San Yi (concubine) |

| Issue | Danzhu Ehuang Nuying |

| Father | Emperor Ku |

| Mother | Qingdu |

| Emperor Yao | |

|---|---|

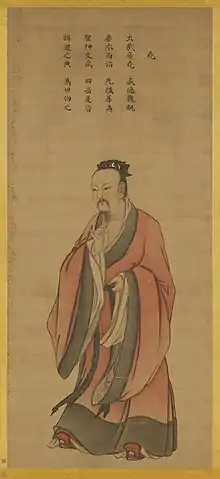

Song dynasty depiction of Yao |

Emperor Yao (simplified Chinese: 尧; traditional Chinese: 堯; pinyin: Yáo; Wade–Giles: Yao2; traditionally c. 2356 – 2255 BCE)[2] was a legendary Chinese ruler, according to various sources, one of the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors.

Ancestry and early life

Yao's ancestral name is Yi Qi (伊祁) or Qi (祁), clan name is Taotang (陶唐), given name is Fangxun (放勳), as the second son to Emperor Ku and Qingdu (慶都). He is also known as Tang Yao (唐堯).[3][4]

Yao's mother has been worshipped as the goddess Yao-mu (堯母).[5]

Legends

According to the legend, Yao became the ruler at 20 and died at 99 when he passed his throne to Shun the Great, to whom he had given his two daughters in marriage.[6] According to the Bamboo Annals, Yao abdicated his throne to Shun in his 73rd year of reign, and continued to live during Shun's reign for another 28 years.

It was during the reign of Emperor Yao that the Great Flood began, a flood so vast that no part of Yao's territory was spared, and both the Yellow River and the Yangtze valleys flooded.[7] The alleged nature of the flood is shown in the following quote:

Like endless boiling water, the flood is pouring forth destruction. Boundless and overwhelming, it overtops hills and mountains. Rising and ever rising, it threatens the very heavens. How the people must be groaning and suffering!

According to both historical and mythological sources, the flooding continued relentlessly. Yao sought to find someone who could control the flood, and turned for advice to his special adviser, or advisers, the Four Mountains (四嶽, Sìyuè); who, after deliberation, gave Emperor Yao some advice which he did not especially welcome. Upon the insistence of Four Mountains, and over Yao's initial hesitation, the person Yao finally consented to appoint in charge of controlling the flood was Gun, the Prince of Chong, who was a distant relative of Yao's through common descent from the Yellow Emperor.[9]

Even after nine years of the efforts of Gun, the flood continued to rage on, leading to the increase of all sorts of social disorders. The administration of the empire was becoming increasingly difficult; so, accordingly, at this point, Yao offered to resign the throne in favor of his special adviser(s), Four Mountains: however, Four Mountains declined, and instead recommended Shun – another distant relative to Yao through the Yellow Emperor; but one who was living in obscurity, despite his royal lineage.[10]

Yao proceeded to put Shun through a series of tests, beginning with marrying his two daughters to Shun and ending by sending him down from the mountains to the plains below where Shun had to face fierce winds, thunder, and rain.[11] After passing all of Yao's tests, not the least of which being establishing and continuing a state of marital harmony together with Yao's two daughters, Shun took on administrative responsibilities as co-emperor.[12] Among these responsibilities, Shun had to deal with the Great Flood and its associated disruptions, especially in light of the fact that Yao's reluctant decision to appoint Gun to handle the problem had failed to fix the situation, despite having been working on it for the previous nine years. Shun took steps over the next four years to reorganize the empire, in such a way as to solve immediate problems and to put the imperial authority in a better position to deal with the flood and its effects.

Bamboo Annals

The Bamboo Annals represent Yao as having banished prince Danzhu to Danshui in his 58th year of reign. They add that following Yao's abdication in favor of Shun, Danzhu kept away from Shun, and that following the death of Yao, "Shun tried to yield the throne to him, but in vain."

However, an alternative account found elsewhere in the Annals offers a different story. It holds that Shun dethroned and imprisoned Yao, then raised Danzhu to the throne for a short time before seizing it himself.[13]

Legacy

Often extolled as the morally perfect and intelligent sage-king, Yao's benevolence and diligence served as a model to future Chinese monarchs and emperors. Early Chinese accounts often speak of Yao, Shun and Yu the Great as historical figures, and contemporary historians believed they may represent leader-chiefs of allied tribes who established a unified and hierarchical system of government in a transition period to the patriarchal feudal society. In the Classic of History, one of the Five Classics, the initial chapters deal with Yao, Shun and Yu.

Of his many contributions, Yao is said to have invented the game of Weiqi (Go), reportedly to favorably influence his vicious playboy son Danzhu.[14] After the customary three-year mourning period after Yao's death, Shun named Danzhu as the ruler but the people only recognized Shun as the rightful heir.

Astronomical observations

According to some Chinese classic documents such as Yao Dian (Document of Yao) in Shang Shu (Book of Documents), and Wudibenji (Records for the Five Kings) in the Shiji (Historic Records), Yao assigned astronomic officers to observe celestial phenomena such as the sunrise, sunset, and the rising of the evening stars. This was done in order to make a solar and lunar calendar with 366 days for a year, also providing for the leap month.

Some recent archaeological work at Taosi, an ancient site in Shanxi, dating to 2300 BCE–1900 BCE, may have provided some evidence for this. A sort of an ancient observatory – the oldest in East Asia[15] – was found at Taosi that seems to coincide with the ancient records.[16]

Some Chinese archaeologists believe that Taosi was the site of a state Youtang (有唐) conquered by Emperor Yao and made to be his capital.[17][18]

The structure consists of an outer semi-ring-shaped path, and a semi-round rammed-earth platform with a diameter of about 60 m; it was discovered in 2003–2004.

Dynastic succession

Yao was claimed to be the ancestor of the Han Dynasty Emperor Liu Bang.[19] Other important noble families have also claimed descent through Yellow Emperor.[20]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Records of the Grand Historian

- ↑ Ching, Julia; R. W. L. Guisso (1991). Sages and filial sons: mythology and archaeology in ancient China. The Chinese University Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-962-201-469-5.

- ↑ Sarah Allan (1991). The shape of the turtle: myth, art, and cosmos in early China. SUNY Press. p. 59. ISBN 0-7914-0460-9. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

- ↑ Asiapac Editorial (2006). Great Chinese emperors: tales of wise and benevolent rule (revised ed.). Asiapac Books Pte Ltd. p. 11. ISBN 981-229-451-1. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

- ↑ Yang, 102

- ↑ Asiapac Editorial (2006). Great Chinese emperors: tales of wise and benevolent rule (revised ed.). Asiapac Books Pte Ltd. p. 12. ISBN 981-229-451-1. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

- ↑ Wu 1982, p. 69.

- ↑ Wu 1982, p. 69. Translation by Wu.

- ↑ Wu 1982, p. 69.

- ↑ Wu 1982, pp. 70–71.

- ↑ Wu 1982, pp. 74–76.

- ↑ Wu 1982, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Bamboo Annals

- ↑ Yang, Lihui; Deming An; Jessica Anderson Turner (2005). Handbook of Chinese mythology. ABC-CLIO Ltd. p. 228. ISBN 978-1-57607-806-8.

- ↑ David Pankenier, et al. (2008), The Xiangfen, Taosi site: A Chinese Neolithic 'observatory'?. Archaeologica Baltica 10

- ↑ He Nu, Wu Jiabi (2005), Astronomical date of the "observatory" at Taosi site. Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (IA CASS)

- ↑ 尧的政治中心的迁移及其意义 Archived 2011-09-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Scientists discover Emperor Yao's capital, China Daily, June 19, 2015.

- ↑ Patricia Buckley Ebrey (2003). Women and the family in Chinese history. Vol. 2 of Critical Asian scholarship (illustrated ed.). Psychology Press. p. 171. ISBN 0-415-28823-1. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

- ↑ Fabrizio Pregadio (2008). Fabrizio Pregadio (ed.). The encyclopedia of Taoism, Volume 1 (illustrated ed.). Psychology Press. p. 505. ISBN 978-0-7007-1200-7. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

References

- C.K. Yang. Religion in Chinese Society : A Study of Contemporary Social Functions of Religion and Some of Their Historical Factors (1967 [1961]). Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Sources

- Wu, Kuo-Cheng (1982), The Chinese heritage, New York: Crown Publishers, Inc, ISBN 978-0517544754.

External links

- https://web.archive.org/web/20120415045747/http://threekingdoms.com/history.htm#2_3_1

- https://web.archive.org/web/20070929011102/http://csgo.org/about/history.php