| Paradigm | Query language |

|---|---|

| Developer | W3C |

| First appeared | 1998 |

| Stable release | 3.1

/ March 21, 2017 |

| Influenced by | |

| XSLT, XPointer | |

| Influenced | |

| XML Schema, XForms | |

XPath (XML Path Language) is an expression language designed to support the query or transformation of XML documents. It was defined by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) in 1999,[1] and can be used to compute values (e.g., strings, numbers, or Boolean values) from the content of an XML document. Support for XPath exists in applications that support XML, such as web browsers, and many programming languages.

Overview

The XPath language is based on a tree representation of the XML document, and provides the ability to navigate around the tree, selecting nodes by a variety of criteria.[2][3] In popular use (though not in the official specification), an XPath expression is often referred to simply as "an XPath".

Originally motivated by a desire to provide a common syntax and behavior model between XPointer and XSLT, subsets of the XPath query language are used in other W3C specifications such as XML Schema, XForms and the Internationalization Tag Set (ITS).

XPath has been adopted by a number of XML processing libraries and tools, many of which also offer CSS Selectors, another W3C standard, as a simpler alternative to XPath.

Versions

There are several versions of XPath in use. XPath 1.0 was published in 1999, XPath 2.0 in 2007 (with a second edition in 2010), XPath 3.0 in 2014, and XPath 3.1 in 2017. However, XPath 1.0 is still the version that is most widely available.[1]

- XPath 1.0 became a Recommendation on 16 November 1999 and is widely implemented and used, either on its own (called via an API from languages such as Java, C#, Python or JavaScript), or embedded in languages such as XSLT, XProc, XML Schema or XForms.

- XPath 2.0 became a Recommendation on 23 January 2007, with a second edition published on 14 December 2010. A number of implementations exist but are not as widely used as XPath 1.0. The XPath 2.0 language specification is much larger than XPath 1.0 and changes some of the fundamental concepts of the language such as the type system.

- The most notable change is that XPath 2.0 is built around the XQuery and XPath Data Model (XDM) that has a much richer type system.[lower-alpha 1] Every value is now a sequence (a single atomic value or node is regarded as a sequence of length one). XPath 1.0 node-sets are replaced by node sequences, which may be in any order.

- To support richer type sets, XPath 2.0 offers a greatly expanded set of functions and operators.

- XPath 2.0 is in fact a subset of XQuery 1.0. They share the same data model (XDM). It offers a

forexpression that is a cut-down version of the "FLWOR" expressions in XQuery. It is possible to describe the language by listing the parts of XQuery that it leaves out: the main examples are the query prolog, element and attribute constructors, the remainder of the "FLWOR" syntax, and thetypeswitchexpression.

- XPath 3.0 became a Recommendation on 8 April 2014.[4] The most significant new feature is support for functions as first-class values.[5] XPath 3.0 is a subset of XQuery 3.0, and most current implementations (April 2014) exist as part of an XQuery 3.0 engine.

- XPath 3.1 became a Recommendation on 21 March 2017.[6] This version adds new data types: maps and arrays, largely to underpin support for JSON.

Syntax and semantics (XPath 1.0)

The most important kind of expression in XPath is a location path. A location path consists of a sequence of location steps. Each location step has three components:

- an axis

- a node test

- zero or more predicates.

An XPath expression is evaluated with respect to a context node. An Axis Specifier such as 'child' or 'descendant' specifies the direction to navigate from the context node. The node test and the predicate are used to filter the nodes specified by the axis specifier: For example, the node test 'A' requires that all nodes navigated to must have label 'A'. A predicate can be used to specify that the selected nodes have certain properties, which are specified by XPath expressions themselves.

The XPath syntax comes in two flavors: the abbreviated syntax, is more compact and allows XPaths to be written and read easily using intuitive and, in many cases, familiar characters and constructs. The full syntax is more verbose, but allows for more options to be specified, and is more descriptive if read carefully.

Abbreviated syntax

The compact notation allows many defaults and abbreviations for common cases. Given source XML containing at least

<A>

<B>

<C/>

</B>

</A>

the simplest XPath takes a form such as

/A/B/C

that selects C elements that are children of B elements that are children of the A element that forms the outermost element of the XML document. The XPath syntax is designed to mimic URI (Uniform Resource Identifier) and Unix-style file path syntax.

More complex expressions can be constructed by specifying an axis other than the default 'child' axis, a node test other than a simple name, or predicates, which can be written in square brackets after any step. For example, the expression

A//B/*[1]

selects the first child ('*[1]'), whatever its name, of every B element that itself is a child or other, deeper descendant ('//') of an A element that is a child of the current context node (the expression does not begin with a '/'). The predicate [1] binds more tightly than the / operator. To select the first node selected by the expression A//B/*, write (A//B/*)[1]. Note also, index values in XPath predicates (technically, 'proximity positions' of XPath node sets) start from 1, not 0 as common in languages like C and Java.

Expanded syntax

In the full, unabbreviated syntax, the two examples above would be written

/child::A/child::B/child::Cchild::A/descendant-or-self::node()/child::B/child::node()[position()=1]

Here, in each step of the XPath, the axis (e.g. child or descendant-or-self) is explicitly specified, followed by :: and then the node test, such as A or node() in the examples above.

Here the same, but shorter: A//B/*[position()=1]

Axis specifiers

Axis specifiers indicate navigation direction within the tree representation of the XML document. The axes available are:[lower-alpha 2]

| Full syntax | Abbreviated syntax | Notes |

|---|---|---|

ancestor | ||

ancestor-or-self | ||

attribute |

@ |

@abc is short for attribute::abc |

child | xyz is short for child::xyz | |

descendant |

// |

// is short for /descendant-or-self::node()/ |

descendant-or-self | ||

following | ||

following-sibling | ||

namespace | ||

parent |

.. |

.. is short for parent::node() |

preceding | ||

preceding-sibling | ||

self |

. |

. is short for self::node() |

As an example of using the attribute axis in abbreviated syntax, //a/@href selects the attribute called href in a elements anywhere in the document tree.

The expression . (an abbreviation for self::node()) is most commonly used within a predicate to refer to the currently selected node.

For example, h3[.='See also'] selects an element called h3 in the current context, whose text content is See also.

Node tests

Node tests may consist of specific node names or more general expressions. In the case of an XML document in which the namespace prefix gs has been defined, //gs:enquiry will find all the enquiry elements in that namespace, and //gs:* will find all elements, regardless of local name, in that namespace.

Other node test formats are:

- comment()

- finds an XML comment node, e.g.

<!-- Comment --> - text()

- finds a node of type text excluding any children, e.g. the

helloin<k>hello<m> world</m></k> - processing-instruction()

- finds XML processing instructions such as

<?php echo $a; ?>. In this case,processing-instruction('php')would match. - node()

- finds any node at all.

Predicates

Predicates, written as expressions in square brackets, can be used to filter a node-set according to some condition. For example, a returns a node-set (all the a elements which are children of the context node), and a[@href='help.php'] keeps only those elements having an href attribute with the value help.php.

There is no limit to the number of predicates in a step, and they need not be confined to the last step in an XPath. They can also be nested to any depth. Paths specified in predicates begin at the context of the current step (i.e. that of the immediately preceding node test) and do not alter that context. All predicates must be satisfied for a match to occur.

When the value of the predicate is numeric, it is syntactic-sugar for comparing against the node's position in the node-set (as given by the function position()). So p[1] is shorthand for p[position()=1] and selects the first p element child, while p[last()] is shorthand for p[position()=last()] and selects the last p child of the context node.

In other cases, the value of the predicate is automatically converted to a boolean. When the predicate evaluates to a node-set, the result is true when the node-set is non-empty. Thus p[@x] selects those p elements that have an attribute named x.

A more complex example: the expression a[/html/@lang='en'][@href='help.php'][1]/@target selects the value of the target attribute of the first a element among the children of the context node that has its href attribute set to help.php, provided the document's html top-level element also has a lang attribute set to en. The reference to an attribute of the top-level element in the first predicate affects neither the context of other predicates nor that of the location step itself.

Predicate order is significant if predicates test the position of a node. Each predicate takes a node-set returns a (potentially) smaller node-set. So a[1][@href='help.php'] will find a match only if the first a child of the context node satisfies the condition @href='help.php', while a[@href='help.php'][1] will find the first a child that satisfies this condition.

Functions and operators

XPath 1.0 defines four data types: node-sets (sets of nodes with no intrinsic order), strings, numbers and booleans.

The available operators are:

- The

/,//and[...]operators, used in path expressions, as described above. - A union operator,

|, which forms the union of two node-sets. - Boolean operators

andandor, and a functionnot() - Arithmetic operators

+,-,*,div(divide), andmod - Comparison operators

=,!=,<,>,<=,>=

The function library includes:

- Functions to manipulate strings: concat(), substring(), contains(), substring-before(), substring-after(), translate(), normalize-space(), string-length()

- Functions to manipulate numbers: sum(), round(), floor(), ceiling()

- Functions to get properties of nodes: name(), local-name(), namespace-uri()

- Functions to get information about the processing context: position(), last()

- Type conversion functions: string(), number(), boolean()

Some of the more commonly useful functions are detailed below.[lower-alpha 3]

Node set functions

- position()

- returns a number representing the position of this node in the sequence of nodes currently being processed (for example, the nodes selected by an xsl:for-each instruction in XSLT).

- count(node-set)

- returns the number of nodes in the node-set supplied as its argument.

String functions

- string(object?)

- converts any of the four XPath data types into a string according to built-in rules. If the value of the argument is a node-set, the function returns the string-value of the first node in document order, ignoring any further nodes.

- concat(string, string, string*)

- concatenates two or more strings

- starts-with(s1, s2)

- returns

trueifs1starts withs2 - contains(s1, s2)

- returns

trueifs1containss2 - substring(string, start, length?)

- example:

substring("ABCDEF",2,3)returnsBCD. - substring-before(s1, s2)

- example:

substring-before("1999/04/01","/")returns1999 - substring-after(s1, s2)

- example:

substring-after("1999/04/01","/")returns04/01 - string-length(string?)

- returns number of characters in string

- normalize-space(string?)

- all leading and trailing whitespace is removed and any sequences of whitespace characters are replaced by a single space. This is very useful when the original XML may have been prettyprint formatted, which could make further string processing unreliable.

Boolean functions

- not(boolean)

- negates any boolean expression.

- true()

- evaluates to true.

- false()

- evaluates to false.

Number functions

- sum(node-set)

- converts the string values of all the nodes found by the XPath argument into numbers, according to the built-in casting rules, then returns the sum of these numbers.

Usage examples

Expressions can be created inside predicates using the operators: =, !=, <=, <, >= and >. Boolean expressions may be combined with brackets () and the boolean operators and and or as well as the not() function described above. Numeric calculations can use *, +, -, div and mod. Strings can consist of any Unicode characters.

//item[@price > 2*@discount] selects items whose price attribute is greater than twice the numeric value of their discount attribute.

Entire node-sets can be combined ('unioned') using the vertical bar character |. Node sets that meet one or more of several conditions can be found by combining the conditions inside a predicate with 'or'.

v[x or y] | w[z] will return a single node-set consisting of all the v elements that have x or y child-elements, as well as all the w elements that have z child-elements, that were found in the current context.

Syntax and semantics (XPath 2.0)

Syntax and semantics (XPath 3)

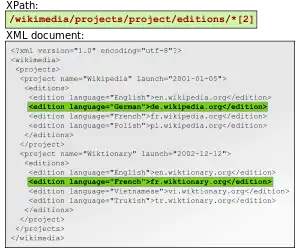

Examples

Given a sample XML document

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<Wikimedia>

<projects>

<project name="Wikipedia" launch="2001-01-05">

<editions>

<edition language="English">en.wikipedia.org</edition>

<edition language="German">de.wikipedia.org</edition>

<edition language="French">fr.wikipedia.org</edition>

<edition language="Polish">pl.wikipedia.org</edition>

<edition language="Spanish">es.wikipedia.org</edition>

</editions>

</project>

<project name="Wiktionary" launch="2002-12-12">

<editions>

<edition language="English">en.wiktionary.org</edition>

<edition language="French">fr.wiktionary.org</edition>

<edition language="Vietnamese">vi.wiktionary.org</edition>

<edition language="Turkish">tr.wiktionary.org</edition>

<edition language="Spanish">es.wiktionary.org</edition>

</editions>

</project>

</projects>

</Wikimedia>

The XPath expression

/Wikimedia/projects/project/@name

selects name attributes for all projects, and

/Wikimedia//editions

selects all editions of all projects, and

/Wikimedia/projects/project/editions/edition[@language='English']/text()selects addresses of all English Wikimedia projects (text of all edition elements where language attribute is equal to English). And the following

/Wikimedia/projects/project[@name='Wikipedia']/editions/edition/text()selects addresses of all Wikipedias (text of all edition elements that exist under project element with a name attribute of Wikipedia).

Implementations

Command-line tools

- XMLStarlet easy to use tool to test/execute XPath commands on the fly.

- xmllint (libxml2)

- RaptorXML Server from Altova supports XPath 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0

- Xidel

C/C++

Free Pascal

- The unit XPath is included in the default libraries

Implementations for database engines

Java

- Saxon XSLT supports XPath 1.0, XPath 2.0 and XPath 3.0 (as well as XSLT 2.0, XQuery 3.0, and XPath 3.0)

- BaseX (also supports XPath 2.0 and XQuery)

- VTD-XML

- Sedna XML Database Both XML:DB and proprietary.

- QuiXPath a streaming open source implementation by Innovimax

- Xalan

- Dom4j

The Java

package javax.xml.xpath has been part of Java standard edition since Java 5[8] via the Java API for XML Processing. Technically this is an XPath API rather than an XPath implementation, and it allows the programmer the ability to select a specific implementation that conforms to the interface.

JavaScript

- jQuery XPath plugin based on Open-source XPath 2.0 implementation in JavaScript

- FontoXPath Open source XPath 3.1 implementation in JavaScript. Currently under development.

.NET Framework

- In the System.Xml and System.Xml.XPath namespaces[9]

- Sedna XML Database

Perl

- XML::LibXML (libxml2)

PHP

- Sedna XML Database

- DOMXPath via libxml extension

Python

- The ElementTree XML API in the Python Standard Library includes limited support for XPath expressions

- libxml2

- Amara

- Sedna XML Database

- lxml

- Scrapy[10]

Ruby

Scheme

- Sedna XML Database

SQL

- MySQL supports a subset of XPath from version 5.1.5 onwards[11]

- PostgreSQL supports XPath and XSLT from version 8.4 onwards[12]

Tcl

- The tDOM package provides a complete, compliant, and fast XPath implementation in C[13]

Use in schema languages

XPath is increasingly used to express constraints in schema languages for XML.

- The (now ISO standard) schema language Schematron pioneered the approach.

- A streaming subset of XPath is used in W3C XML Schema 1.0 for expressing uniqueness and key constraints. In XSD 1.1, the use of XPath is extended to support conditional type assignment based on attribute values, and to allow arbitrary boolean assertions to be evaluated against the content of elements.

- XForms uses XPath to bind types to values.

- The approach has even found use in non-XML applications, such as the source code analyzer for Java called PMD: the Java is converted to a DOM-like parse tree, then XPath rules are defined over the tree.

See also

Notes

- ↑ XPath 2.0 supports atomic types, defined as built-in types in XML Schema, and may also import user-defined types from a schema.

- ↑ XML authority Normal Walsh maintains an excellent online visualization of the axis specifiers.[7] It appears from the illustration that preceding, ancestor, self, descendant, and following form a complete, ordered, non-overlapping partition of document element tree.

- ↑ For a complete description, see the W3C Recommendation document.

References

- 1 2 "XML and Semantic Web W3C Standards Timeline" (PDF). 2012-02-04.

- ↑ Bergeron, Randy (2000-10-31). "XPath—Retrieving Nodes from an XML Document". SQL Server Magazine. Archived from the original on 2010-07-26. Retrieved 2011-02-24.

- ↑ Pierre Geneves (2012). "Course: The XPath Language" (PDF).

- ↑ "XML Path Language (XPath) 3.0". World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). 2014-04-02. Retrieved 2021-07-16.

- ↑ Kay, Michael (2012-02-10). "What's new in 3.0 (XSLT/XPath/XQuery) (plus XML Schema 1.1)" (PDF). XML Prague 2012. Retrieved 2021-07-16.

- ↑ "XML Path Language (XPath) 3.1". World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). 2017-03-21. Retrieved 2021-07-16.

- ↑ Walsh, Norman (1999). "Axis Specifiers". nwalsh.com. Personal blog of venerated XML sage graybeard. Retrieved 2021-02-25.

- ↑ "javax.xml.xpath (Java SE 10 & JDK 10)". Java® Platform, Standard Edition & Java Development Kit Version 10 API Specification. Retrieved 2021-07-17.

Since: 1.5

- ↑ "System.Xml Namespace". Microsoft Docs. 2020-10-25. Retrieved 2021-07-16.

- ↑

Duke, Justin (2016-09-29). "How To Crawl A Web Page with Scrapy and Python 3". Digital Ocean. Retrieved 2017-11-24.

Selectors are patterns we can use to find one or more elements on a page so we can then work with the data within the element. scrapy supports either CSS selectors or XPath selectors.

- ↑ "MySQL :: MySQL 5.1 Reference Manual :: 12.11 XML Functions". dev.mysql.com. 2016-04-06. Archived from the original on 2016-04-06. Retrieved 2021-07-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ "xml2". PostgreSQL Documentation. 2014-07-24. Retrieved 2021-07-16.

- ↑ Loewer, Jochen (2000). "tDOM – A fast XML/DOM/XPath package for Tcl written in C" (PDF). Proceedings of First European TCL/Tk User Meeting. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

External links

- XPath 1.0 specification

- XPath 2.0 specification

- XPath 3.0 specification

- XPath 3.1 specification

- What's New in XPath 2.0

- XPath Reference (MSDN)

- XPath Expression Syntax (Saxon)

- XPath 2.0 Expression Syntax (Saxon),

- XPath - MDC Docs by Mozilla Developer Network

- XPath introduction/tutorial

- XSLT and XPath function reference