The July 15 Incident (Chinese: 七一五事变), known by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) as the July 15 counter-revolutionary coup (Chinese: 七一五反革命政变), and as the Wuhan–Communist split (Chinese: 武汉分共) by the Kuomintang (KMT), occurred on 15 July 1927. Following growing strains in the coalition between the KMT government in Wuhan and the CCP, and under pressure from the rival nationalist government led by Chiang Kai-shek in Nanjing, Wuhan leader Wang Jingwei ordered a purge of communists from his government in July 1927.

Background

During the Northern Expedition (1926–1928) to reunify a fragmented China, Kuomintang policy was one of "allying with Russia and tolerating the communists" (Chinese: 联俄容共) under the First United Front between the KMT and CCP. However, after the anti-communist faction of the KMT led by Chiang Kai-shek organized a massacre of communists and leftists in April 1927, the nationalist government in Wuhan, led by Wang Jingwei, denounced Chiang, who established his own government in Nanjing, marking the start of the Nanjing–Wuhan split. The Wuhan government initially maintained the alliance with the CCP but later, tension escalated between them. Warlords such as Feng Yuxiang, who commanded large military forces, also called for severing of ties with the Communist Party.

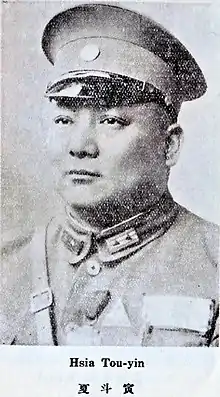

KMT leftist–CCP relations remained close after the "Shanghai massacre" purge of communists by Chiang Kai-shek on 12 April, and joint KMT–CCP conferences continued to be held frequently.[1] Workers and farmers' movements continued to grow, but some KMT generals and soldiers, especially those from landowning or merchant families, were disturbed by an increase in class warfare killings.[2] Xu Kexiang, the KMT regimental commander of the 33rd regiment, 35th army launched an operation to disarm the communists on 21 May (Chinese: 马日事变), and before long, Xia Douyin, the commander of the 14th Independent Division, also led an anti-communist mutiny. Although the Wuhan government had ordered their suppression, under the protection of warlord He Jian and other officials, they succeeded in defecting to the Nanjing government, which led to Wuhan losing control of parts of Hubei and most of Hunan.[3] On 29 June, Wuhan garrison commander Li Pinxian and He Jian openly declared their support for the anti-communist cause, and dispersed the Hankou strikers and their militant forces. As disruption and discord continued at Wuhan, the Communist International (Comintern) issued a series of orders known as the "May Instructions" on 1 June, which Wang thought would destroy the KMT. Under increasing pressure, Wang decided to break with the communists and the Soviet Union.

Events of 15 July

On 15 July, Wang Jingwei held a meeting within KMT, during which he formally publicised the content of the "May Instructions" and condemned CCP's decisions, though he maintained the position that non-violent methods should be used to remove the communists from Wuhan. This proposal met with approval from most members; the only one who protested and walked out was Soong Ching-ling's representative Eugene Chen. In the end, the meeting passed the "Policy of Uniting the Party", a statement that was directed against CCP's declaration, requesting that all the communists within the KMT and the army immediately declare their withdrawal from the CCP or face immediate suspension. Additionally, the Wuhan government sent envoys to Moscow to discuss how to bilaterally guarantee the freedom and safety of the communists who were about to withdraw. After Wang was made aware of the CCP declaration of 13 July, on the following day, in the name of the political committee presidium, he accused the communist party of having "ruined the revolution", and suspended all the communists from the Wuhan government.[4]

Chief Soviet advisor to the Wuhan government Mikhail Borodin left Wuhan secretly sometime between 13 and 16 July. Upon hearing of his having left, General He Jian opened fire on Borodin's former headquarters, and martial law was declared. KMT forces loyal to Chiang Kai-shek gradually began to take over the city, and Jian's troops raided leftist strongholds and arrested or killed those who had not fled.[5][6] Soviet military advisor Vasily Blyukher escaped an assassination attempt as he left the city for Shanghai, where he bid farewell to Chiang, who allowed him to escape to Russia.[6] By the 18th, Wuhan was awash in anti-communist, anti-Soviet, and anti-Borodin propaganda posters.[7] Although the Wuhan government was purging communists, this did not immediately mean that their confrontation with Chiang Kai-shek had ended, and they persisted in regarding him as "the only enemy to our country and party".[8]

In response to the purge, CCP forces launched the Nanchang uprising against the KMT Wuhan government on 1 August, beginning the Chinese Civil War, and on the 19th, the Wuhan government reconciled with the Nanjing government.[9]

See also

References

- ↑ 《李宗仁回忆录》,333页

- ↑ 李守中 (2010). 中國二百年:從馬戛爾尼訪華到鄧小平南巡 1793-1992. 遠流出版. pp. 321–322. ISBN 978-957-32-6620-4.

- ↑ 《中苏关系史纲》 第二章 苏联援助下的国民革命 “五月指示”与国共分家

- ↑ 郭廷以《近代中國史綱》(下冊)第十五章第三節,香港中文大學出版社1996年版, ISBN 962-201-352-X, 562頁。

- ↑

- Jacobs, Dan N. (1981). Borodin: Stalin's Man in China. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 284. ISBN 0-674-07910-8.

- 1 2 Pakula, Hannah (3 November 2009). The Last Empress: Madame Chiang Kai-shek and the Birth of Modern China. Simon and Schuster. p. 163. ISBN 9781439154236.

- ↑

- Jacobs, Dan N. (1981). Borodin: Stalin's Man in China. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 285. ISBN 0-674-07910-8.

- ↑ 《蔣介石三次下野秘录》,76页

- ↑ "Nanchang uprsing" (PDF).