William Sinclair | |

|---|---|

| Earl (Jarl) of Orkney Earl of Caithness Lord Sinclair Baron of Roslin | |

Earl of Orkney, Earl of Caithness, Lord Sinclair and Baron of Roslin Coats of Arms | |

| Predecessor | Henry II Sinclair, Earl of Orkney |

| Successor | William Sinclair, 2nd Earl of Caithness William Sinclair, 3rd Lord Sinclair Oliver St Clair, 12th Baron of Roslin |

| Died | c. 1480 |

| Noble family | Clan Sinclair |

| Father | Henry Sinclair, 2nd Earl of Orkney |

| Mother | Egidia Douglas |

William Sinclair (1410–1480), 1st Earl of Caithness (1455–1476), last Earl (Jarl) of Orkney (1434–1470 de facto, –1472 de jure), 2nd Lord Sinclair and 11th Baron of Roslin was a Norwegian and Scottish nobleman and the builder of Rosslyn Chapel, in Midlothian.[1]

In The Scots Peerage by James Balfour Paul he is designated as the 1st Lord Sinclair,[2] but historian Roland Saint-Clair designates him the 2nd Lord Sinclair in reference to his father, Henry II Sinclair, Earl of Orkney, being the first person recorded as Lord Sinclair by public records.[3]

Early life

He was the son of Henry II Sinclair, Earl of Orkney and Egidia Douglas, daughter of Sir William Douglas of Nithsdale and maternal granddaughter of Robert II of Scotland. He was also the grandson of Henry I Sinclair, Earl of Orkney.[4]

His father Henry, who had been a de facto Jarl of Orkney, died in 1420; William travelled to Copenhagen in 1422 to establish his claim to the Jarldom, but David Menzies was appointed instead, to rule as William's guardian until he came of age. In 1424, William succeeded in wresting de facto control of the earldom from his guardian, but it was not until 1434 that he was acknowledged as Jarl of Orkney by King Eric VII of Denmark, Norway and Sweden, sovereign of Orkney.[5][6]

Earl of Orkney

On succeeding to the Earldom of Orkney, William had barely been in possession of it for a year when he was one of five earls selected to be among twenty hostages, proposed on 31 May 1421, for the redemption of James I of Scotland. When that redemption could not be obtained, he was then placed on the list of nobles who received a passport to visit James I, who was then a prisoner in England. The earl received a safe conduct for himself and twenty-four persons. James I returned to Scotland in 1424 and he was met at Durham by the Earl of Orkney as well as the Earls of Lennox, Wigtown, Moray, Crawford, March, Angus and Stratherne.[1]

In 1423, David Menzies of Wemyss, chief of the Clan Menzies and uncle of William, was entrusted by King Eric with the administration of the Isles, and the Bishop of Orkney subscribed to this obligation as surety. However, due to disorder during the reign of Menzies, the government of the earldom was reinstated to the Bishop for seven years until the young Earl William could formally receive his investiture. However, the young William had taken the title of earl before receiving his investiture as he is styled as Earl of Orkney in 1426 at the assize in Stirling, and again in 1428 when he was present at Edinburgh dealing with a complaint made by his mother regarding the spoilation of her Nithsdale possessions.[1]

In 1434, William crossed over to Denmark and King Eric granted investiture to him for the Earldom of Orkney. Earl William was also to hold Kirkwall Castle for the king and his successors. In the same year James I of Scotland's daughter, Margaret, was betrothed to Louis, Dauphin of France and Charles VII of France then arranged for Margaret to be escorted back to France. The King of Scotland ordered that all should be ready by 20 June, and William, Earl of Orkney had forty-six ships in readiness to transport Margaret and her train. The fleet that carried her to her future kingdom was commanded by the Earl of Orkney.[1]

In 1446, the Earl of Orkney laid the foundation stone of the Collegiate Church of St Matthew, commonly referred to as Rosslyn Chapel.[7] In the same year the Earl of Orkney was called to the Norwegian Riksråd to take the oath of Christopher of Bavaria who was the successor of King Eric of Denmark, Norway and Sweden.[1]

After the death of childless King Christopher of Norway in 1448, Earl William was mentioned as a possible candidate for the vacant throne, as the jarl of Orkney was the highest ranking nobleman in Norway. However, there are no indications that he pursued this claim.[8] The same year the Earl of Orkney appears obtaining the patronage of the chapel of Saint Duthac in Kirkwall.[1]

.jpg.webp)

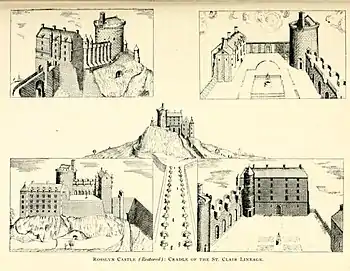

In 1454–55, the Earls of Orkney and Angus laid siege to Abercorn Castle with 6,000 men because Lord Hamilton was in league with the rebel Earl of Douglas. Hamilton was taken by the royal camp and the Earl of Orkney kept him in honourable captivity in Roslin Castle for a few days until he defected from the House of Douglas.[1]

On 15 November 1456, the earl's father-in-law, Alexander Sutherland of Dunbeath, made his will in the earl's presence at Roslin Castle. The earl had married Sutherland's daughter Marjory, by Sutherland's wife Mariota, daughter of Donald of Islay, Lord of the Isles.[1]

James II of Scotland died in 1460 and the Earl of Orkney was elected as one of six Governors for the government during the minority of the young James III of Scotland.[1]

In 1468, James III of Scotland married Margaret, daughter of Christian I of Norway, Sweden and Denmark. Christian was unable to immediately provide a dowry. Instead, he promised that dowry would be provided at a later date, pledging the territory of the Jarldom of Orkney as security for his promise. The sovereignty of Orkney therefore transferred from Norway to Scotland.[1] In 1470, James III offered William the castle and lands of Ravenscraig in Fife,[9] in return for William quitclaiming his rights in Orkney and Shetland, an offer William accepted.[1]

The Norse jarldom technically remained in existence, but William now only had authority over the mainland parts - Caithness and Sutherland. In 1472, it having become clear that the dowry was unlikely to be paid, James declared the Jarldom's territory to be forfeit to the Scottish Crown, to which it was annexed by an Act of the Scottish Parliament, on 20 February. William now wielded his authority under the king of Scotland, rather than of Norway.[1][10]

Earl of Caithness

Exchanging his inherited lordship of Nithsdale for lands in Caithness, William was granted the hereditary title Earl of Caithness in 1455.[11][10] He resigned the Earldom in favour of his second son from his second marriage, William, in 1476.[1]

William, Earl of Orkney died before 3 July 1480.[1]

Family

William Sinclair was married three times: firstly to Lady Elizabeth Douglas, daughter of Archibald Douglas, 4th Earl of Douglas; secondly to Marjory Sutherland (married 1456), daughter of Alexander Sutherland of Dunbeath; and thirdly to Janet Yeman.[12]

By Lady Elizabeth Douglas he had the following children:

- William Sinclair, 3rd Lord Sinclair who was reportedly disinherited by his father, only receiving Ravenscraig Castle in Fife.

- Lady Catherine Sinclair, who married Alexander Stewart, Duke of Albany.

- Elizabeth Sinclair, who married Andrew, Master of Rothes

By Marjory Sutherland he had the following children:

- Oliver St Clair, 12th Baron of Roslin, who received the Barony of Roslin.[13]

- William Sinclair, 2nd Earl of Caithness (b. 1460 - d. 1513)[13]

- Alexander Sinclair (c. 1454)

- George Sinclair (c. 1453)

- Robert Sinclair (1447)

- Arthur Sinclair (c. 1452)

- Lady Eleanor Sinclair (b. 1457- d. 1518), who married John Stewart, 1st Earl of Atholl.

- Lady Elizabeth Sinclair (b. c. 1455 - d. 1498), who married the Laird of Houston.

- Lady Margaret Sinclair (c. 1450), who married David Boswell of Balmuto.

- Lady Katherine Sinclair (b. 1440 - d. 1479)

- Lady Susan Sinclair (c. 1451)

- Lady Marjory Sinclair (1455–80), married Andrew Leslie, Master of Rothes. With Andrew she had issue including William Leslie, 3rd Earl of Rothes

- Lady Mariota Sinclair (c. 1455)

- Lady Euphemia Sinclair (c. 1470), who married John Kincaid Laird of Warriston.

Illegitimate:

- Sir David Sinclair of Sumburgh, died 1507.[14]

The earl's second son of his second marriage, William Sinclair, became the designated heir of the Earldom of Caithness, and continued that title. The Barony of Roslin went to his first son by that marriage, Sir Oliver Sinclair.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Saint-Clair, Roland William (1898). The Saint-Clairs of the Isles; being a history of the sea-kings of Orkney and their Scottish successors of the sirname of Sinclair. Shortland Street, Auckland, New Zealand: H. Brett. pp. 112-126 and 186. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ↑ Paul, James Balfour (1910). The Scots Peerage; Founded on Wood's Edition of Sir Robert Douglas's Peerage of Scotland; Containing an Historical and Genealogical Account of the Nobility of that Kingdom. Vol. VII. Edinburgh: David Douglas. pp. 569. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ↑ Saint-Clair, Roland (1898). The Saint-Clairs of the Isles; being a history of the Sea-kings of Orkney and their Scottish successors of the sirname of Sinclair. Shortland Street, Auckland, New Zealand: H. Brett. p. 297. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ↑ Paul, James Balfour (1909). The Scots Peerage : Founded on Wood's ed. of Sir Robert Douglas's Peerage of Scotland; containing an historical and genealogical account of the nobility of that kingdom. Vol. VI. Edinburgh: David Douglas. p. 568-571. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ↑ Thomson, William P.L (2008). The New History of Orkney. Edinburgh. pp. 174–179.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Grohse, Ian Peter; Magnussen, Stefan (2022). "The Earldom of Orkney, the Duchy of Schleswig and the Kalmar Union in 1434". Scandinavian Journal of History. 48 (2): 137–156. doi:10.1080/03468755.2022.2138533. hdl:10037/28535. ISSN 0346-8755. S2CID 253327161.

- ↑ Cowan, Ian B; Easson, David E (1976). Medieval Religious Houses. p. 225. ISBN 0582120691.

- ↑ Hamre, Lars (1968). Norsk historie frå omlag år 1400. Oslo. p. 128.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "Ravenscraig Castle". undiscoveredscotland.co.uk. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- 1 2 Burke, Bernard (1869). Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Peerage and Baronetage of the British Empire. 59 Pall Mall, London: Harrison. p. 1016. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ↑ Paul, James Balfour (1905). The Scots Peerage : Founded on Wood's ed. of Sir Robert Douglas's Peerage of Scotland; containing an historical and genealogical account of the nobility of that kingdom. Vol. II. Edinburgh: David Douglas. p. 332-337. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ↑ Paul, James. The Scots Peerage. Vol. ii. pp. 333–336.

- 1 2 Henderson, John W.S (1884). Caithness Family History. Edinburgh: David Douglas. pp. 1-4.

- ↑ Thomson, William P.L. (1987). History of Orkney. Edinburgh. pp. 134–136.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- Charles Mosley, Burke's Peerage and Baronetage, 107th edition.

- Sir James Balfour Paul, The Scots Peerage : founded on Wood's ed. of Sir Robert Douglas's Peerage of Scotland; containing an historical and genealogical account of the nobility of that kingdom. Edinburgh 1904.