Painting of William Caslon, founder of the Caslon type foundry, by Francis Kyte. He holds his specimen of his types. | |

| Industry | Type foundry |

|---|---|

| Founded | c. 1720 |

| Founder | William Caslon |

| Defunct | 1937 |

| Successor | Stephenson Blake |

| Headquarters | , |

| Products | Metal type Caslon typeface |

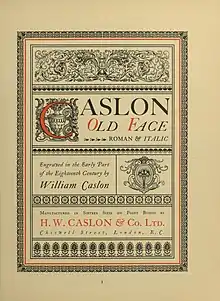

The Caslon type foundry was a type foundry in London which cast and sold metal type. It was founded by the punchcutter and typefounder William Caslon I, probably in 1720. For most of its history it was based at Chiswell Street, Islington, was the oldest type foundry in London, and the most prestigious.[1]

In the nineteenth century, the company established a division selling printing equipment. This section of the company continues to operate as of 2021, and is now branded Caslon Ltd. and based in St. Albans. The type foundry section of the company was bought by Stephenson Blake in 1937.

From 1793 to 1819 a separate Caslon foundry was operated by William Caslon III and then his son William Caslon IV, who split off from the family business. This was also bought by a predecessor company of Stephenson Blake.

Background

Metal type was traditionally made by punchcutting, carefully cutting punches in steel used to stamp matrices, the moulds used to cast metal type.

Type foundries operated in London from the early days of printing. Some punchcutters worked in London in the seventeenth century, including Arthur Nicholls[2] and Joseph Moxon, who wrote a manual of how type was made. However, London was seemingly not a hub of skill in typefounding and many of the types available in London were of poor quality.[3][lower-alpha 1] In the second half of the seventeenth century the Dutch Republic was one of the largest centres of printing expertise, and both Oxford University Press in 1670–2[4] and the London typefounder John James in 1710 imported matrices from it.[5]

William Caslon I and II

William Caslon (1692 – 23 January 1766) was an engraver who had come to London from Cradley, Worcestershire. He began a career in London with work like cutting the royal coat of arms into government firearms and tooling for bookbinders. The quality of his work came to the attention of printers, who engaged him to cut first Arabic and then roman type.[9] Specimens of the Caslon foundry published under the management of William Caslon II but in William Caslon I's lifetime wrote that he established his type foundry in 1720.[10][lower-alpha 3] His first roman type appeared around 1725; Caslon is the name now given to designs based on his work.[14][15]

Caslon's premises as a gun engraver were based in Vine Street, Minories.[16] He later moved to Helmet Row, then Ironmonger Row from 1727 to 1736, and in 1737 had moved to Chiswell Street, where it would remain for the next two hundred years.[17][6]

The foundry was successful by 1730[18] and issued a first specimen around that time.[19] Its first dated specimen appeared in 1734 and the inclusion of a specimen of its types in Chambers' Encyclopaedia made it well-known.[6][20] By 1763 its stock had expanded to be shown in book form.[21]

Caslon's type designs were based closely on the seventeenth-century Dutch types popular in London at the time, cut by punchcutters including Nicolaes Briot and the Voskens family.[22][23][lower-alpha 4] In James Mosley's view, they were intended as "unobtrusive substitutes" for specific types his clients already used, and closely resembled them.[25] Besides this, some types he sold came from other founders. He jointly valued the Grover type foundry in 1728 with John James of the James Foundry,[26] although ultimately he did not buy it, and he did buy part of the foundry of Robert Mitchell in 1739. Some older types were sold by the foundry, including a display typeface cut by Moxon.[27]

By the end of Caslon's life his types were quite conservative in design, although very popular.[28] They therefore did not follow the more delicate, stylised and experimental "transitional" styles gaining ground in Europe taking inspiration from calligraphy and copperplate engraving.[lower-alpha 5] Alfred F. Johnson notes that his 1764 specimen "might have been produced a hundred years earlier".[29] Stanley Morison described Caslon's type as "a happy archaism".[30] His other types were also close copies of earlier designs: his blackletter types on textura designs, originally French and long standard in British printing,[31][lower-alpha 6] his Greek types on the sixteenth century Grecs du roi model[36][37] and his Armenian type on types cut in the Netherlands by Miklós Kis.[38]

Caslon trained his son William Caslon II (1720–1778) to also be a punchcutter. He was cutting his own types at the latest by 1738[lower-alpha 7] and by 1746 the firm was styled as "W. Caslon & Son".[39] William Caslon I retired from the business in 1758 and moved out of the city to Bethnal Green.[40]

The firm's labour history was not always harmonious. The firm had two apprentices, Thomas Cottrell and Joseph Jackson. According to Jackson's later client and friend John Nichols, when Jackson showed a punch he had made to William Caslon II, Caslon II hit him and threatened him with gaol.[41] Jackson had in fact secretly drilled a hole through a wall to observe Caslon I teaching his son how to cut punches.[41] Nichols wrote that after a dispute over the price of labour, Caslon II dismissed Cottrell and Jackson on suspicion of organising a deputation of workmen appealing to his retired father.[41] They later set up as type founders themselves, first jointly before Jackson established his own foundry.[41] According to Edward Rowe Mores, Caslon's brother Samuel worked at the foundry for a time as a mould maker before quitting following a dispute and moving back to Birmingham to work for another type founder, Anderton.[42]

William Caslon II continued the business with success until his death in 1778.[43] In c. 1774 – 1778, he introduced some very large poster-size types, likely intended for stagecoach services.[44][45]

Competitors

The firm's competitors evolved over its existence. At the start of its existence, its main competitors were in London, especially the James foundry, which through purchasing the Grover and other foundries took over almost all the other London foundries which preceded Caslon, but gradually declined; on John James' death in 1772 it was purchased by the antiquarian and insurance pioneer Edward Rowe Mores for historical value.[46] Alexander Wilson set up a Scottish type foundry in the 1740s and the low cost of labour in Scotland allowed it to undercut London prices.[47]

By the time of William Caslon I's death, and certainly by the death of William Caslon II, aesthetic tastes were on the verge of changing.[48] John Baskerville's 1757 edition of Virgil, printed in new types taking inspiration from calligraphy, attracted considerable attention. Baskerville's types were proprietary to him and only used by him and some printers he was connected with in Birmingham, but other founders rapidly began to create types in the same style.[49]

Despite this, the Caslon style continued to be popular with printers. The Fry foundry of Bristol first entered the market in 1764 with copies of Baskerville's types, but finding them not commercially successful, proceeded to then produce copies of Caslon's, to the outrage of the Caslon family.[lower-alpha 8]

The anonymous introduction to a 1787 Fry foundry specimen frankly admitted "The plan on which they first sat out, was an improvement of the Types of the late Mr Baskerville of Birmingham...but the shape of Mr. Caslon's Type has since been copied by them with such accuracy as not to be distinguished from those of that celebrated Founder."[50][lower-alpha 9] Decades later, Dr. Edmund Fry, the foundry's last owner, commented that the foundry began operations

"about the year 1764, commencing with improved imitations of Baskerville's fonts...but they did not meet the encouraging approbation of the Printers, whose offices generally, throughout the kingdom, were stored from the London and Glasgow Founderies with types of the form introduced by the celebrated William Caslon...By the recommendation, therefore, of several of the most respectable printers of the Metropolis, Doctor Fry, the proprietor, commenced his imitation of the Chiswell Street Foundery...at vast expense, and with very satisfactory encouragement, during the completion of it."[lower-alpha 10][49]

James Mosley describes the Fry Foundry imitation of the Caslon types as "a very close copy that is not easy to tell from the original."[51][52]

1778 to 1809

%252C_after_Charles_Catton_the_Elder.png.webp)

Since William Caslon II died intestate in 1778, ownership of the foundry was divided between his widow, Elizabeth (née Cartlitch), (1730–1795) and their two sons: William Caslon III (1754–1833), and his younger brother Henry until his death in 1788.[43][13] Henry Caslon's widow was Elizabeth, née Rowe.[43] An obituary of William Caslon II's widow Elizabeth Caslon in the Freemason's Magazine of March 1796 felt that:

An arduous task now devolved on Mrs. Elizabeth Caslon...the entire management of a very large concern did not, however, come with that weight which it would have borne upon one unaccustomed to the habits of business. Mrs Caslon...had for many years habituated herself to the arrangements of the foundry; so that when the entire care devolved upon her, she manifested powers of mind beyond expectation from a female not then in very early life. In a few years her son, the present Mr. William Caslon, became an active co-partner with his mother, but a misunderstanding between them caused a secession, and they separated their concerns...the urbanity of her manners, and her diligence and activity in the conduct of so extensive a concern, attached to her interest all who had dealings with her, and the steadiness of her friendship rendered her death highly lamented by all who had the happiness of being in the extensive circle of her acquaintance.[53]

.jpg.webp)

The London printer Thomas Curson Hansard saw the fifteen years of the foundry's history after William Caslon II died in 1778 (the period of Hansard's childhood) as a period of stagnation, with "little augmentation" to its stock of punches.[54] Hansard wrote in Typographia, his 1825 textbook on printing:

It will not appear extraordinary that a property so divided and under the management of two ladies, though both superior and indeed extraordinary women, should be unable to maintain its ground triumphantly against the active competition which had for some time existed against it. In fact, the fame of the first William Caslon was peculiarly disadvantageous to Mrs. Caslon, as she never could be persuaded that any attempt to rival him could possibly be successful.[54]

The foundry issued a new specimen book in 1785 and separate specimen of its large capitals,[55] showcasing a range of complex printers' flowers and interlocking designs. James Mosley felt that the specimen of 1785 contained "little that is really new", with only two new typefaces compared to 1766, a script and an extra size of Syriac, although new flowers had been added.[28][lower-alpha 11] It attacked imitators of the Caslon foundry's types, writing that "the acknowledged excellence of this foundry...has excited the jealousy of the envious".[56]

William Caslon III decided to leave the family business in 1792, buying up the foundry of Joseph Jackson (see below). In 1793, the major type founders in London formed a society or association, with the goal of functioning as a cartel for price fixing.[57] Both Elizabeth Caslons attended for the Caslon foundry. William Caslon, now running his own foundry, also joined for his company.[58][lower-alpha 12] Elizabeth Caslon, the wife of William Caslon II, died in 1795. According to Hansard "the foundry was put up for auction in March 1799 and was bought by Mrs. Henry Caslon for £520. Such was the depreciation of the Caslon letter foundry, of which a third share, in 1792, sold for £3000."[60][lower-alpha 13] A. E. Musson felt that although the foundry had depreciated, this value exaggerated the situation and the price "was doubtless because she [Elizabeth Caslon, née Rowe] and her young son already had a large share in the firm."[61]

Elizabeth Caslon decided to renew the foundry's materials, moving on from the types of William Caslon I which were going out of fashion. According to Hansard:

The management of the foundry devolved on Mrs. Henry Caslon, who, possessing an excellent understanding, and being seconded by servants of zeal and ability, was enabled, though suffering severely under ill health, in a great measure to retrieve its credit. Finding the renown of William Caslon no longer efficacious in securing the sale of his types, she resolved to have new fonts cut. She commenced the work of renovation with a new canon, double pica, and pica, having the good fortune to secure the services of John Isaac Drury, a very able engraver, since deceased. The Pica, an improvement on the style of Bodoni, was particularly admired, and had a most extensive sale. Finding herself, however, from the impaired state of her health...unable to sustain the exertions required in conducting so extensive a concern, she resolved, after the purchase of the foundry, to take as an active partner Mr. Nathaniel Catherwood, who by his energy and knowledge of business fully equalled her expectations.[lower-alpha 15]

Much of Drury's work survives intact in the collection of St Bride Library.[67][62]

From 1807 the foundry was paid to cast a new "Porson typeface" for Greek for Cambridge University Press based on the handwriting of classicist Richard Porson, which had been cut by punchcutter Richard Austin.[68][lower-alpha 16] The design became successful and was widely imitated.[70][71][72][73] The foundry seemingly had no input into the design of the punches (it did strike the matrices)[68] and the Porson types were apparently exclusive to Cambridge, but the Caslon foundry later issued types from its own punchcutters in similar design (see below).[74] Less successfully, around 1802–4, the foundry was commissioned to make Rusher's Patent Type, an attempt to create a new paper-saving typeface with no descenders. The type did not become popular.[75][76][lower-alpha 17]

The second Caslon type foundry

William Caslon III decided to move out of the family business. William Caslon I's apprentice Joseph Jackson had established a successful foundry at Dorset Street, Salisbury Square, near Fleet Street.[78][lower-alpha 18] When he died childless in 1792, William Caslon III bought up the Jackson foundry and sold his shares in the family business. He moved the foundry to Finsbury Square.[81] Caslon apparently became bankrupt on January 5, 1793,[82][83] but later rebuilt the business, moving it back to Salisbury Square. (Jackson's apprentice Vincent Figgins, who had hoped to take the foundry over, received support to set his own foundry up from his old client John Nichols.) He apparently was able to take matrices for non-Latin and textura types from his family foundry on leaving the business, and these appear in his specimens.[79]

In 1807 William Caslon III's son, William Caslon IV took over the business. In 1810 he introduced a new kind of matrix, which he called Sans-pareil. These were made by cutting out the letter form in sheet metal and riveting it to a backing plate. This allowed very large letters to be cast more easily.[84][lower-alpha 19]

Some time before 1816, Caslon IV introduced a new sans-serif typeface, the first ever, which was branded as "Egyptian".[85][86][87] In 1819, Caslon sold the foundry and it was bought by Blake, Garnett & Co., which became Stephenson Blake of Sheffield.[78][lower-alpha 20]

1809 onwards

.jpg.webp)

Both Elizabeth Caslon (now Elizabeth Strong, since her remarriage) and Nathaniel Catherwood died in 1809, and the business was taken over by her son Henry Caslon and Catherwood's brother, John Hames Catherwood.[90] In the view of James Mosley, they renewed the foundry's material "completely, making the firm a credible competitor in the sale of modern-face text types and the big new commercial letters which had been developed during the first two decades of the century."[91][92]

During the early nineteenth century, the foundry employed as punchcutter Anthony Bessemer, the father of the industrialist Sir Henry Bessemer.[93] Henry Caslon was Henry Bessemer's godfather and namesake.[94][95] Bessemer later set up his own foundry.[96]

In 1821, a Caslon & Catherwood specimen introduced a reverse-contrast typeface design, the first known, which it named 'Italian'.[97][89][98][99][100][101][lower-alpha 21][103] It had also issued new Greek typefaces by 1821 influenced by the Porson style; in Bowman's view they are "largely Porsonic, but never entirely so".[104][105] Catherwood left the firm in 1821 and later joined the Bessemer foundry,[106][107][108] and the company foreman Martin William Livermore became a partner.[109]

In 1841, the Caslon foundry issued a specimen book showing its large range of typefaces, including fat face, slab-serif and sans-serif display typefaces, besides its range of text faces.[110] Example pages are shown below:

Fat-face typeface

Fat-face typeface Fat face italic; the sample text "VANWAYMAN" shows its range of swash capitals

Fat face italic; the sample text "VANWAYMAN" shows its range of swash capitals Shaded

Shaded Antique (slab-serif) italic

Antique (slab-serif) italic Shaded slab serif

Shaded slab serif_shaded_typeface.jpg.webp) Shaded slab-serif

Shaded slab-serif Condensed sans-serif italic capitals

Condensed sans-serif italic capitals Rounded and shaded sans-serif

Rounded and shaded sans-serif Italian (reverse-contrast) typeface

Italian (reverse-contrast) typeface Ultra-bold modern blackletter

Ultra-bold modern blackletter

In the mid-1840s, the Chiswick Press began using the original Caslon types again for book printing, and they gradually returned to popularity with fine book printers for high-class printing in a traditional style.[111][112]

However, in 1846 the foundry was put up for auction because of Henry Caslon's declining health.[113] The sale catalogue offered "to capitalists...a most valuable property for investment...containing the original works of its founder, William Caslon, which have been recently much in request for reprints, also a most extensive modern foundry".[114] The sale did not reach the reserve price and the foundry continued under the ownership of the Caslon family.[114] The sale catalogue which survives is however historically notable, as it lists the punchcutters of each of the foundry's more modern types from about 1795.[114][115]

On Henry Caslon's death in 1850, the foundry was taken over by his son, Henry William Caslon.[lower-alpha 22] In the same year, the Caslon foundry bought up the London branch of the Wilson foundry.[91] Yet again, changing tastes and probably the acquisitions of types from Wilson led to expansion in the foundry's stock; Johnson notes that "very few types are the same" in the 1857 specimen as in 1841.[118][119]

Henry William Caslon was not successful as an owner of the company; its manager Thomas White Smith later wrote that Caslon was a man "of generous impulse, but of little wisdom in business matters" and losses led to an attempt to cut the wages of workers, leading to a strike.[91] A later article wrote that "during one of these disagreements...Caslon was so apprehensive of personal violence that, to avoid a bombardment of rotten eggs and other objectionable missiles, he took the prudent course of leaving the foundry by a window which opened on to the parade ground at the rear of the premises."[91][120]

On 14 July 1874, Henry William Caslon died at home in Medmenham; he was the last lineal male descendant of William Caslon.[121] Despite the reports of labour unrest, his employees donated a memorial window to the local church commemorating him.[122] The foundry was taken over by its manager, Thomas White Smith. He proved to be extremely successful as a promoter of the company, establishing a company magazine, Caslon's Circular, developing a French branch of the company based in Paris, and licensing display types from abroad.[123][124][125] He wrote in a privately printed autobiography:

Feeling, naturally, regret that the honoured and historical name of "Caslon" should die out...my sons, at my request and recommendation, took the necessary legal steps to add the prefix Caslon to their own, and are now known as Caslon-Smiths. For myself I retain my own name and still subscribe myself Thos. W. Smith.[126][127]

The Caslon-Smith family (now named Caslon) continued to own the Caslon type foundry for the rest of its existence, and as of 2021 continue to own Caslon Ltd.[128][129]

In the late nineteenth century, the foundry's historic materials and building remained largely intact, retaining an eighteenth-century sales ledger[8] and a letter from the eccentric Philip Thicknesse, a Caslon family friend.[130] However, the foundry switched from casting some of Caslon's original types, now branded as Caslon Old Face, with facsimiles that could be cast by machine.[111]

Twentieth century

By the late nineteenth century it was clear that for large-run printing of body text the future was hot metal typesetting, which cast fresh new type for each printing job, and in the case of the Linotype machine cast each line in rigid blocks. In 1897 James Figgins of the Figgins foundry commented "the Lino is ruining us entirely".[131]

The Caslon foundry continued to be prosperous for some more decades, licensing the Cheltenham typeface from American Type Founders[132] and issuing a specimen designed by the leading printer George W. Jones.[111][133] The old house that had been the foundry's base for over 170 years was demolished in 1910 and replaced by modern premises.[134][135][136][137] During the 1920s and 1930s it manufactured several types designed by Eric Gill for fine presses.[138][139]

Legacy

The Caslon foundry ceased trading at the end of 1936 and was liquidated the following year.[140][141]

The company name and many punches and matrices were bought up by Stephenson Blake, especially those of its best-selling types including the Caslon Old Face materials.[142][143] The Monotype Corporation, meanwhile, bought up many of the other punches, including many nineteenth-century types and sets of decorated wood alphabets it had bought from the Pouchée foundry.[140][144][145] These were later taken over by the St Bride Library, while Stephenson Blake's materials passed to the Type Archive collection when it ceased to cast metal type.[142]

The printing equipment division and the French branch of the company became separate companies after the takeover. Materials of the Paris branch of the company, the Fonderie Caslon, are now held by the Musée de l'imprimerie, Nantes,[142] while as of 2022 the printing equipment division, Caslon Ltd., continues in business, now based in St. Albans.[128]

Digital fonts

Besides the many digitisations of William Caslon I's original types, several digital fonts based on the Caslon Foundry's later types have been published.[146]

Designer Paul Barnes in particular has published a large series of digitisations of types from Caslon and other early nineteenth century British foundries through his company Commercial Type, under the imprint Commercial Classics.[147] This includes Brunel, a large family based on the work of John Isaac Drury and revivals of many other Caslon typefaces.[148][149][150][151][152] Jonathan Hoefler published a blackletter typeface, Parliament, based on the ultra-bold Caslon Foundry blackletter types of the early nineteenth century;[153][154] another blackletter font family based on the Caslon Foundry's blackletter types is Avebury by Jim Parkinson.[155]

List of names and proprietors of the foundry

_(1941).jpg.webp)

- 1809–1821: Henry Caslon II and F. F. Catherwood

- 1821–1840: Henry Caslon II, H. W. Caslon and M. W. Livermore (trading as Caslon, Son and Livermore)

- 1840–1850: Caslon & Son

- 1850–1873: H. W. Caslon and Co.

Notes

- ↑ Making metal type required a range of techniques which could easily go wrong, including justifying matrices (carefully filing them down so the letters would be properly spaced) and pouring metal into the mould so it filled every space and no air bubbles were left to spoil the types' appearance.

- ↑ Mosley identifies other non-Caslon types as the Samaritan and Syriac, and "it is difficult to believe that the lower case of the Small Pica no. 1...can be Caslon's work unless it is an early attempt. It was replaced in 1742, the only one of the roman types to be abandoned in this way."[8]

- ↑ His family later had a tradition that he established his foundry in 1716,[11] although 1720 is the date on William Caslon II's specimens made in his father's lifetime.[12][10] Neil Macmillan in An A–Z of Type Designers suggests that the foundry opened "probably in 1722 or 1723".[13]

- ↑ Briot, who was based in Amsterdam, is not to be confused with the French engraver Nicholas Briot.[24]

- ↑ For instance the romain du roi type of the previous century, the work of Pierre-Simon Fournier in Paris, Fleischmann in Amsterdam and the Baskerville type of John Baskerville in Birmingham that appeared towards the end of Caslon's career.

- ↑ As an example, his Two-Line Great Primer Black was based on an original perhaps from Paris or Rouen and dating back to around 1504, of which Harry Carter believed at least one copy existed.[32] One was used by Wynkyn de Worde, and Plantin and the type foundries of Voskens,[33] and James in London, had similar matrices. The type was shown in the OUP 1707 specimen and in a c. 1665 British specimen possibly from the foundry of Nicholas Nicholls.[32] (According to Mosley Caslon’s punches survive at St Bride’s.[8]) Other copies or duplicate matrices proliferated; the Wilson foundry showed one in 1786 (many of his texturas were purchased from James)[34] and William Caslon III in his breakaway foundry had one; his texturas came from the Caslon foundry as duplicate matrices or from the James foundry via Jackson.[34] A near copy was sold by the Fry foundry; according to Edmund Fry this was cut in house.[35]

- ↑ And possibly earlier: according to Edward Rowe Mores he cut the foundry's Anglo-Saxon characters which appeared on its specimens by 1734.

- ↑ The company's founder Dr. Joseph Fry also ran a chocolate business. Its name survives in Fry's Chocolate Cream and Fry's Turkish Delight.

- ↑ The specimen is included in a reprint edition of John Smith's The Printer's Grammar, published by T. Evans and with an introduction credited to an anonymous editor.

- ↑ The Glasgow foundry is presumably the foundry of Alexander Wilson.

- ↑ The main 1785 specimen does not show William Caslon II's titling capitals.[28] Whereas William Caslon II certainly cut punches, it is not clear if the later Caslon men did. One of the ship designs in the specimen appeared heading the "Shipping" column on the first front page of the Daily Universal Register, later The Times.[28]

- ↑ William Caslon later left, but the Caslon foundry remained as a member for the rest of the association's existence. It remained in operation intermittently until at least 1820, although a witness to a Select Committee in 1824 reported informal collusion between foundries to keep wages of workmen low was continuing.[59]

- ↑ Modernised to avoid confusion. Hansard wrote 520l and 3000l, a common way of writing £ at the time.

- ↑ Paul Barnes comments that this size (Canon or 48pt) only has some features of late eighteenth-century transitional typefaces: "[it] is more a transitional and shows a hesitation in design not found in the text sizes. This face seems to disappear from all specimens known."[64]

- ↑ Hansard wrote that Elizabeth Caslon, after remarrying Mr. Strong, died in Bristol in March 1809 after facing illness with "truly admirable" fortitude and is buried in Bristol Cathedral. If Hansard's information is correct, she may be the Elizabeth Strong with a memorial in the cathedral who died March 3rd, 1809.[66]

- ↑ Most of Austin's punches survive at St. Bride library.[69]

- ↑ Frederic Goudy thought that the new non-descending characters had been poorly made, with different stroke widths to the modern-face they were added to.[75]

- ↑ Jackson, although apparently very talented, is extremely poorly documented: no complete specimen survives from his foundry in his lifetime.[79][80] William Caslon III issued specimens and it seems likely that most of the types shown are Jackson's, but according to Vincent Figgins II he employed at least one other punchcutter, and it is known that his foundry burned down in 1790 and he was in poor health for the last two years of his life. He had materials from the James foundry including texturas and Stephenson Blake in the twentieth century still had his matrices for a sixteenth-century Greek type cut by Pierre Haultin, although again this is poorly documented in the Caslon-era specimens for his foundry because Caslon III seemingly took duplicate matrices for exotic types on leaving the family business which he tended to show on his specimens.[79]

- ↑ Casting large letters from punched matrices was difficult to do due to the complexity of driving in a large punch. Other methods were previously used including casting type or matrices in sand, but sans-pareil matrices were reusuable and much easier than sand-casting. An 1820s source claimed that Jackson had worked on large types, although no specimen of them is known, and Vincent Figgins is recorded as stating that they were new in 1810.[84] Justin Howes has speculated that this is a confusion with the fact that the successors to his foundry introduced them, while James Mosley has speculated that Jackson began work on them but the Caslons finished the project.

- ↑ Caslon is known to have had other industrial interests, which apparently included a gasworks, later amalgamated into the Gas Light and Coke Company.[88]

- ↑ On the 1821 specimen the title page is undated but 1821 is on the front board. On both of the two surviving copies, the name is changed in pen from "Caslon and Catherwood" to "Henry Caslon"; see below.[102]

- ↑ In 1840, Gertrude Catherwood, wife of Frederick Catherwood, an artist, architect and explorer who was John Catherwood's son, had left him for Henry W. Caslon. The episode became a well-known court case after Catherwood sued. Caslon countered that they had never been validly married under Church of England law because they were married in Beirut by an American missionary.[116] A jury found for Catherwood, but the House of Lords ruled for Caslon four years later. H. W. Caslon married Gertrude in 1853.[117]

References

- ↑ Barker & Collins 1983, p. 87.

- ↑ Lane 1991, pp. 301–303.

- ↑ Lane 1991, p. 297.

- ↑ Hart 1900, p. 162–166.

- ↑ Mosley 1981, p. 8.

- 1 2 3 Lane 1993, p. 78.

- ↑ Mosley, James (2008). "William Caslon the elder". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 3 Mosley 1981.

- ↑ Mosley, James. "A lost Caslon type: Long Primer No 1". Type Foundry (blog). Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- 1 2 Reed & Johnson 1974, p. 239.

- ↑ "Messrs. Caslon and Co's Dinner". The Printers' Journal and Typographical Magazine. September 3, 1866. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ↑ Mosley 1967, p. 67.

- 1 2 Macmillan, Neil (1 January 2006). An A–Z of Type Designers. Yale University Press. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-0-300-11151-4. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ↑ Mosley 1967, p. 73.

- ↑ Reed & Johnson 1974, p. 256.

- ↑ Mosley 1967, pp. 68.

- ↑ Mosley 1967, pp. 73–74.

- ↑ Reed & Johnson 1974, p. 233.

- ↑ Mosley 1967, pp. 74, 76.

- ↑ Mosley 1967, p. 76.

- ↑ Mosley 1981, p. 11.

- ↑ "John Lane & Mathieu Lommen: ATypI Amsterdam Presentation". YouTube. ATypI. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- ↑ Lane 2013, pp. 408–9.

- ↑ de Jong, Feike. "The Briot project. Part I". PampaType. TYPO, republished by PampaType. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ↑ Mosley 1981, p. 9.

- ↑ Treadwell 1980, pp. 48–53.

- ↑ Mosley 1981, p. 22.

- 1 2 3 4 Mosley 1981, p. 14.

- ↑ Johnson, A.F. Type Designs. pp. 52–3.

- ↑ Morison, Stanley (1937). "Type Designs of the Past and Present, Part 3". PM: 17–81. Archived from the original on 2017-09-04. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ↑ Mores 1961, pp. 113–115.

- 1 2 Mores 1961.

- ↑ Type Specimen Facsimiles 2

- 1 2 Lane 1991.

- ↑ Reed & Johnson 1974.

- ↑ Bowman 1998, pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Lane 1996.

- ↑ Lane 2012, pp. 104–107, 129–130.

- ↑ Mosley 1981, p. 10.

- ↑ Howes, Mosley & Chartres 1998, p. 12.

- 1 2 3 4 Nichols 1812, p. 359.

- ↑ Mores 1961, p. 80.

- 1 2 3 Hansard 1825, p. 351.

- ↑ Wolpe 1964, pp. 59–62.

- ↑ Howes, Justin (2004). "Caslon's Patagonian". Matrix. 24: 61–71.

- ↑ Lane 1991, p. 319.

- ↑ Musson 1955, p. 89.

- ↑ Reed, Talbot Baines (1890). "Old and New Fashions in Typography". Journal of the Society of Arts. 38: 527–538. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- 1 2 Reed 1887, p. 310.

- ↑ Smith, John (1787). Anonymous (ed.). The Printer's Grammar. pp. 271–316. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ↑ Mosley, James. "Comments on Typophile thread". Typophile. Archived from the original on 28 September 2017. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

In about 1770 the Fry foundry, whose first types in the 1760s were what they called an 'improvement' of Baskerville's, had also made an imitation of the smaller sizes of the Caslon Old Face types – a very close copy that is not easy to tell from the original. In 1907 Stephenson, Blake had recast this Caslon look-alike from original matrices and began to sell it under the name of Georgian Old Face.

- ↑ Sherman, Nick; Mosley, James (9 July 2012). "The Dunlap Broadside". Fonts in Use. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ↑ "Mrs. Elizabeth Caslon, with a portrait". Freemason's Magazine, Or General and Complete Library. J.W. Bunney. 1796.

- 1 2 Hansard 1825, pp. 351–2.

- ↑ Mosley 1984, p. 27.

- ↑ Caslon, William (1785). A Specimen of Printing Types. London. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ↑ Musson 1955, pp. 89–90.

- ↑ Musson 1955, p. 90.

- ↑ Musson 1955, p. 101.

- ↑ Hansard 1825, pp. 352.

- ↑ Musson 1955, p. 86.

- 1 2 Barnes, Paul. "Brunel Collection: Read the story". Commercial Type. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ↑ Caslon, Elizabeth (c. 1799). [Untitled fragment of a specimen of printing types]. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ↑ @commerclassics (March 15, 2019). "The first moderns of the Eliz. Caslon & the Caslon foundry are here: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/collections/a-specimen-of-printing-types#/?tab=about Largest size Canon (48 pt) is more a transitional and shows a hesitation in design not found in the text sizes. This face seems to disappear from all specimens known" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ↑ Savage 1822, p. 20.

- ↑ "Strong, Elizabeth, d. 1809; BRSBC.M428 on eHive". eHive.

- ↑ Walters, John; Barnes, Paul. "New bottle old wine". Eye. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- 1 2 Bowman 1998, p. 108.

- ↑ Bowman 1998, p. 114.

- ↑ Bowman 1998, p. 118.

- ↑ Bowman 1996, pp. 131–134.

- ↑ Mosley, James. "Porson's Greek type design". Type Foundry. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

- ↑ Mosley, James (1960). "Porson's Greek Types". The Penrose Annual. 54: 36–40. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

- ↑ Bowman 1998, p. 119.

- 1 2 Goudy, Frederic (1 January 1977). Typologia: Studies in Type Design & Type Making, with Comments on the Invention of Typography, the First Types, Legibility, and Fine Printing. University of California Press. pp. 141–142. ISBN 978-0-520-03308-5.

- ↑ John Cheney and His Descendants: Printers in Banbury Since 1767. Banbury. 1936. pp. 26–31.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Caslon, William IV (1816). [Untitled fragment of a specimen book of printing types, c. 1816]. London: William Caslon IV. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- 1 2 Howes, Mosley & Chartres 1998, p. 30.

- 1 2 3 Lane 1991, p. 320.

- ↑ Fraas, Mitch (9 January 2014). "Always check the endpapers". Unique at Penn. University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- ↑ Howes, Mosley & Chartres 1998, pp. 20, 30.

- ↑ "Bankrupts". Universal Magazine. 1793. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

William Caslon, of Finsbury-square, letter-founder

- ↑ Christian, Edward (1818). The Origin, Progress, and Present Practice of the Bankrupt Law: Both in England and in Ireland. W. Clarke and Sons. pp. 379–380.

- 1 2 Musson 1955, p. 99.

- ↑ Mosley, James. "The Nymph and the Grot: an Update". Typefoundry blog. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ↑ Tracy, Walter (2003). Letters of credit : a view of type design. Boston: David R. Godine. ISBN 9781567922400.

- ↑ Mosley, James. "Comments on Typophile thread – "Unborn: sans serif lower case in the 19th century"". Typophile (archived). Archived from the original on 28 June 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ↑ Mills, Mary (2001). "The Dutton Street Gasworks" (PDF). Newsletter of the Camden History Society (183).

- 1 2 Specimen of Printing Types. Caslon & Catherwood/Henry Caslon. 1821. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

- ↑ Reed 1887, p. 253.

- 1 2 3 4 Mosley 1993a, p. 35.

- ↑ Morlighem 2020, p. 9.

- ↑ Report of the Committee of the Society of Arts (etc.) Together with the Approved Communications and Evidence Upon the Same, Relative to the Mode of Preventing the Forgery of Bank Notes. 1819. pp. 68–9.

- ↑ Bessemer 1905, pp. 4–8.

- ↑ "Sir Henry Bessemer's Connection with Printing". The Printing Times and Lithographer: 226–7. 1880. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ↑ "A. Bessemer's Specimen of Printing Types, 1830". Journal of the Printing Historical Society. 5. 1969.

- ↑ Barnes, Paul; Schwartz, Christian. "Type Tuesday". Eye magazine. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ↑ Barnes, Paul. "Caslon Italian Collection". Commercial Type. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ↑ Shaw, Paul (5 October 2010). "Arbor, a Fresh Interpretation of Caslon Italian". Print. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ↑ Shields, David (2008). "A Short History of the Italian". Ultrabold: The Journal of St Bride Library (4): 22–27.

- ↑ Tracy, Walter (2003). Letters of Credit: A View of Type Design. Boston: David R. Godine. ISBN 9781567922400.

- ↑ Mosley 1984, p. 29.

- ↑ Shaw 2017, p. 124.

- ↑ Bowman 1998, pp. 119–124.

- ↑ Bowman 1996, p. 133.

- ↑ Reed 1887, pp. 359–360.

- ↑ "No. 18239". The London Gazette. 18 April 1826. p. 913.

- ↑ "No. 18500". The London Gazette. 29 August 1828. p. 1638.

- ↑ Reed 1887, p. 254.

- ↑ Caslon, Henry (1841). Specimen of Printing Types by Henry Caslon, Chiswell Street, London: Letter-Founder to Her Majesty's Honourable Board of Trade. London. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- 1 2 3 Mosley, James. "Recasting Caslon Old Face". Type Foundry. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ↑ Ovink, G.W. (1971). "Nineteenth-century reactions against the didone type model – I". Quaerendo. 1 (2): 18–31. doi:10.1163/157006971X00301.

- ↑ "[Advertisement] To Capitalists". The Athenaeum. W. Lewer. 10 October 1846. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

The present proprietor, by whose ancestor it was established...is induced to part with [the foundry] from his increasing infirmities.

- 1 2 3 Mosley 1984, p. 58.

- ↑ Reed & Johnson 1974, pp. 250–251.

- ↑ Carrington, Frederick Augustus; Marshman, Joshua Ryland; Court, Great Britain Central Criminal (1843). Reports of Cases Argued and Ruled at Nisi Prius: In the Courts of Queen's Bench, Common Pleas, & Exchequer. S. Sweet. pp. 431–433. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ↑ Aguirre, Robert (2009). "Catherwood, Frederick (1799–1854)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/38316. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Specimen of Printing Types of the Caslon and Glasgow Letter Foundry, Chiswell Street, London. H.W. Caslon and Company. 1857. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ↑ Reed & Johnson 1974, p. 251.

- ↑ "The Caslon Letter Foundry". British Printer. 1905. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ↑ Tucker, Joan (15 March 2012). Ferries of the Upper Thames. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4456-2007-7. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ↑ Bigmore & Wyman 1880, p. 105.

- ↑ Mosley 1993a, pp. 36–37, 42.

- ↑ "Atelier de Typographie de Défense de la France". Musée de la résistance en ligne. Fondation de la Résistance. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ↑ Bassett, John (November 1890). "Eminent Living Printers No. IX: Mr Henry James Tucker". The Inland Printer. Chicago. pp. 150–151. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ↑ Mosley 1993a, p. 42.

- ↑ Squire, Sir John Collings; Scott-James, Rolfe Arnold (1923). "The Late Mr. Sydney Caslon". The London Mercury. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- 1 2 Eccles, Simon. "Best of British: A historic type firm that's still at the cutting edge". Printweek. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ↑ "Caslon Limited". Companies House. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ↑ Reed 1887, p. 245.

- ↑ Mosley 1993a, p. 37.

- ↑ Specimens of types & borders and illustrated catalogue of printers' joinery and materials. London: H. W. Caslon & Co. Ltd. 1915. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ↑ Wallis, Lawrence (2004). George W. Jones: Printer Laureate (1st ed.). Nottingham, England: Plough Press. pp. 101–2. ISBN 9780972563673.

- ↑ Howes, Mosley & Chartres 1998, p. 14.

- ↑ @GraphicGirl (April 19, 2021). "Dammit, the newspaper archive is the perfect procrastination tool 😱 From 1999 article on desktop publishing to Caslon and Stephenson Blake merge (1937), the history of Caslon foundry (1910) …" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ↑ "At The Caslon Letter Foundry". Spitalfields Life. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- ↑ "William Caslon, Letter Founder". Spitalfields Life. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- ↑ Mosley, James. "Eric Gill and the Cockerel Press". Upper & Lower Case. International Typeface Corporation. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ Mosley, James (1982). "Eric Gill and the Golden Cockerel Type". Matrix. 2: 17–23.

- 1 2 Mosley 1993a, p. 34.

- ↑ Reed & Johnson 1974, p. 253.

- 1 2 3 Mosley, James. "The materials of typefounding". Typefoundry. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- ↑ Howes 2000.

- ↑ Daines, Mike. "Pouchee's lost alphabets". Eye Magazine. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ↑ Mosley 1993b, p. 1.

- ↑ "Caslon". Fonts In Use. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ↑ Barnes, Paul (10 July 2019). "The Past is the Present with Paul Barnes". Vimeo. Type@Cooper. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ↑ Barnes, Paul. "Isambard: read the story". Commercial Type. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ↑ Barnes, Paul. "Notes on Notes". Commercial Type. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ↑ Schwartz, Christian. "Brunel". Christian Schwartz. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ↑ "Caslon Rounded Collection". Commercial Type. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ↑ "Caslon French Antique". Commercial Type. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ↑ "Typefaces". Jonathan Hoefler. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ↑ "Parliament: How to use". Hoefler & Co. Monotype. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ↑ Parkinson, Jim. "Avebury". Jim Parkinson. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

Cited literature

- Barker, Nicolas; Collins, John (1983). A Sequel to An Enquiry into the Nature of Certain Nineteenth Century Pamphlets by John Carter and Graham Pollard.; The Forgeries of H. Buxton Forman & T.J. Wise Re-examined. London: Scolar Press. ISBN 9780859676380.

- Ball, Johnson (1973). William Caslon, Master of Letters. The Roundwood Press.

- Bessemer, Henry (1905). Sir Henry Bessemer, F.R.S.: an autobiography; with a concluding chapter. London: Engineering.

- Bowman, J. H. (1992). Greek Printing Types in Britain in the Nineteenth Century: A Catalogue. Oxford: Oxford Bibliographical Society. ISBN 9780901420503.

- Bigmore, E. C.; Wyman, C. W. H. (1880). A Bibliography of Printing: Volume I. London: Bernard Quaritch. pp. 103–109. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- Bowman, J. H. (1996). "Greek Type Design: the British Contribution". In Macrakis, Michael S. (ed.). Greek Letters: From Tablets to Pixels. Oak Knoll Press. pp. 129–144. ISBN 9781884718274.

- Bowman, J. H. (1998). Greek Printing Types in Britain: from the late eighteenth century to the early twentieth century. Thessaloniki: Typophilia. ISBN 9789607285201.

- Carter, Harry (1965). "Caslon Punches: An Interim Note". Journal of the Printing Historical Society. 3: 68–70.

- Hansard, Thomas Curson (1825). Typographia: An Historical Sketch of the Origin and Progress of the Art of Printing. Baldwin, Cradock and Joy.

- Hart, Horace (1900). Notes on a Century of Typography at the University Press, Oxford, 1693–1794. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- Howes, Justin; Mosley, James; Chartres, Richard (1998). "A to Z of Founder's London: A showing and synopsis of ITC Founder's Caslon" (PDF). Friends of the St. Bride's Printing Library. St Bride Library. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 November 2005. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- Howes, Justin (2000). "Caslon's punches and matrices". Matrix. 20: 1–7.

- Johnson, Alfred F. (1936). "A Note on William Caslon" (PDF). Monotype Recorder. 35 (4): 3–7. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- Johnson, Alfred F. (1970). Selected essays on books and printing. Van Gendt & Co. ISBN 9789063000165.

- Lane, John A. (1991). "Arthur Nicholls and his Greek Type for the King's Printing House". The Library. Series 6. 13 (4): 297–322. doi:10.1093/library/s6-13.4.297.

- Lane, John A. (1993). "The Caslon Type Specimen in the Museum Van Het Boek". Quaerendo. 23 (1): 78–79. doi:10.1163/157006993X00235.

We now know that Caslon moved from Old Street to Chiswell Street in 1737/8. As far as we know, all of the Chiswell Street specimens dated "1734" were issued in various editions of the Chambers' Cyclopedia from 1738 to 1753.

- Lane, John A. (1996). "From the Grecs du Roi to the Homer Greek: Two Centuries of Greek Printing Types in the Wake of Garamond". In Macrakis, Michael S. (ed.). Greek Letters: From Tablets to Pixels. Oak Knoll Press. ISBN 9781884718274.

- Lane, John A. (2012). The Diaspora of Armenian Printing, 1512-2012. Amsterdam: Special Collections of the University of Amsterdam. pp. 70–86, 211–213. ISBN 9789081926409.

- Lane, John A. (2013). "The Printing Office of Gerrit Harmansz van Riemsdijck, Israël Abrahamsz de Paull, Abraham Olofsz, Andries Pietersz, Jan Claesz Groenewoudt & Elizabeth Abrahams Wiaer c. 1660–1709". Quaerendo. 43 (4): 311–439. doi:10.1163/15700690-12341283.

- Mores, Edward Rowe (1961). Carter, Harry; Ricks, Christopher (eds.). A dissertation upon English typographical founders and founderies (1778) : with a catalogue and specimen of the type-foundry of John James (1782). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- Morlighem, Sébastien (2014). The 'modern face' in France and Great Britain, 1781-1825: typography as an ideal of progress (PhD). University of Reading.

- Morlighem, Sébastien (2020). Robert Thorne and the Introduction of the 'modern' fat face. Poem.

- Morlighem, Sébastien (2021). "Dusting Latin Type History #1 on the Origin of Bold and Fat Faces with Sébastien Morlighem". Vimeo. Type@Cooper. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- Mosley, James (1967). "The Early Career of William Caslon". Journal of the Printing Historical Society: 66–81.

- Mosley, James (1981). "A specimen of printing types cut by William Caslon, London 1766; A facsimile with introduction and notes". Journal of the Printing Historical Society. 16: 1–113.

- Mosley, James (1984). British type specimens before 1831: a hand-list. Oxford Bibliographical Society/University of Reading.

- Mosley, James (1993a). "The Caslon Type Foundry in 1902: Selections from an Album". Matrix. 13: 34–42.

- Mosley, James (1993b). Ornamented types: twenty-three alphabets from the foundry of Louis John Poucheé. I.M. Imprimit in association with the St. Bride Printing Library.

- Mosley, James (2001). "Memories of an Apprentice Typefounder". Matrix. 21: 1–13.

- Mosley, James (2004). "Jackson, Joseph (1733–1792)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/14539. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Musson, A. E. (1955). "The London Society of Master Letter-Founders, 1793–1820". The Library. s5-X (2): 86–102. doi:10.1093/library/s5-X.2.86.

- Nichols, John (1812). Literary Anecdotes of the Eighteenth Century: Comprizing Biographical Memoirs of William Bowyer, Printer, F.S.A., and Many of His Learned Friends; an Incidental View of the Progress and Advancement of Literature in this Kingdom During the Last Century; and Biographical Anecdotes of a Considerable Number of Eminent Writers and Ingenious Artists; with a Very Copious Index. Vol. 2. Printed for the author , by Nichols, Son, and Bentley ...

- Reed, Talbot Baines (1887). A History of the Old English Letter Foundries. Elliot Stock. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- Reed, Talbot Baines; Johnson, Alfred F. (1974). A History of the Old English Letter Foundries. ISBN 9780712906357. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- Savage, William (1822). Practical Hints on Decorative Printing. London. p. 72.

- Shaw, Paul (April 2017). Revival Type: Digital Typefaces Inspired by the Past. Yale University Press. pp. 79–84. ISBN 978-0-300-21929-6.

- Treadwell, Michael (1980). "The Grover typefoundry". Journal of the Printing Historical Society. 15: 36–53.

- Wolpe, Berthold (1964). "Caslon Architectural: On the origin and design of the large letters cut and cast by William Caslon II". Alphabet. pp. 57–72.