.jpg.webp)

Wildlife trafficking practices have resulted in the emergence of zoonotic diseases. Exotic wildlife trafficking is a multi-billion dollar industry that involves the removal and shipment of mammals, reptiles, amphibians, invertebrates, and fish all over the world.[1] Traded wild animals are used for bushmeat consumption, unconventional exotic pets, animal skin clothing accessories, home trophy decorations, privately owned zoos, and for traditional medicine practices. Dating back centuries, people from Africa,[2][3] Asia,[4][5][6][7] Latin America,[8][9] the Middle East,[10] and Europe[11] have used animal bones, horns, or organs for their believed healing effects on the human body. Wild tigers, rhinos, elephants, pangolins, and certain reptile species are acquired through legal and illegal trade operations in order to continue these historic cultural healing practices. Within the last decade nearly 975 different wild animal taxa groups have been legally and illegally exported out of Africa and imported into areas like China, Japan, Indonesia, the United States, Russia, Europe, and South America.[12]

Consuming or owning exotic animals can propose unexpected and dangerous health risks. A number of animals, wild or domesticated, carry infectious diseases and approximately 75% of wildlife diseases are vector-borne viral zoonotic diseases.[13] Zoonotic diseases are complex infections residing in animals and can be transmitted to humans. The emergence of zoonotic diseases usually occurs in three stages. Initially the disease is spread through a series of spillover events between domesticated and wildlife populations living in close quarters. Diseases then spread through series of direct contact methods, indirect contact methods, contaminated foods, or vector-borne transmissions. After one of these transmission methods occurs, the disease then rises exponentially in human populations living in close proximities.[14]

After the appearance of the COVID-19 pandemic, whose origins have been linked to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, China, Elizabeth Maruma Mrema, the acting executive secretary of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, called for a global ban on wildlife markets to prevent future pandemics.[15] Others have also called for a total ban on the global wildlife trade[16] or for already existing bans to be enforced, in order both to reduce cruelty to animals as well as to reduce health risks to humans,[17][18] or to implement other disease control intervention measures in lieu of total bans.[19][20][21]

Types of zoonotic disease transmissions

Direct contact transmissions occur when humans encounter first hand contaminated feces, urine, water sources, or bodily fluids. Bodily fluid transmission may happen either from ingesting pathogens or through open wound contact. Indirect contact transmissions occur when humans interact within an infected species' habitat. Humans are often exposed to contaminated soils, plants, and surfaces where bacterial germs are present. Contaminated food transmissions occur when humans eat infected bushmeat, vegetables, fruits, or drink contaminated water. Often these food and water supplies are tainted by fecal pellets of infected bats, birds, or monkeys. Vector-borne transmissions occur when individuals are bitten by infected parasites such as ticks or insects like mosquitos and fleas.[22]

Other factors for escalated disease transmissions include climate change, globalization of trade, accelerated logging practices, irrigation increases, sexual activity between individuals, blood transfusions, and urbanization developments near infected ecosystems.[23]

Health risks of zoonotic diseases

Exotic wildlife trafficking admits a number of infectious diseases that spell potential life-threatening results for human populations if contracted. Researchers believe eliminating the transmission of infectious diseases is not plausible. Instead, creating health screening services is critical for minimizing transmission rates among populations and infected wildlife species involved in trafficking.

Annually, 15.8% of human deaths have been associated with dangerous infectious disease outbreaks linked to exotic trafficking.[24] Researchers, zoologists, and environmentalists determine that financially poor countries in Africa may attribute to nearly 44% of these deaths due to zoonosis related diseases.[24]

Cultural determinants and disease exposure in Africa

People in Africa are exposed to an increased risk of contracting and dispatching life-threatening zoonotic infections. The continent is considered a hot spot for emerging disease transmissions for reasons like socio-culture livelihood interests, livestock farming, land use methods, globalization influences, and consumption behavior practices.[25]

Socio-cultural livelihood factors

Many Africans make a living from the wildlife trade due to the high market demand for exotic animals. These individuals partaking in poaching activities are able to produce an income by selling to vendors all around the world. However, hunters are highly susceptible to encountering infected droplets, water sources, soils, carcasses, and viral airborne pathogens while traveling through the bush. Once they have successfully hunted and killed the wild animal, they run the risk of blood or bodily fluid transfer from close contact with possible infected species. They're also at an increased risk of harvesting arthropod-borne pathogens carried in ticks. Often ticks can be found on the wild animal or in its surrounding wildlife habitat.[26]

Livestock and land use methods

A study conducted in Tanzania revealed major gaps in locals knowledge of zoonotic diseases. Individuals in these pastoral communities acknowledged health symptoms commonly found in both humans and animals, however they did not have a synthesized term for zoonosis and believed pathogens were not life-threatening. Researchers found that the pastoral communities were more concerned with keeping cultural practices of producing cooked meals rather than the potential infections harvested from the animals.[25]

Globalization influence

The urbanization of new environments in Africa increases the migration patterns of humans. New settlements and tourist attractions near these wildlife habitats bring vulnerable individuals with no disease immunity closer to areas of diseases.[25]

Consumption behaviors

The greatest possibility of contracting deadly zoonotic diseases occurs during the bushmeat cooking process. Cooking exotic bushmeat requires sharp knives, steady handwork, and skilled techniques when correctly butchering an animal. Consumers often purchase bushmeat directly from African poachers. This means they have no way of knowing whether the wild animal is carrying dangerous zoonotic pathogens. On average people cut themselves 38% of the time when butchering bushmeat, allowing for infected bodily fluid transmissions. African women are more likely to contract these dangerous zoonotic pathogens because they are the ones handling and cooking the bushmeat.[26]

Zoonoses in wildlife markets

If sanitation standards are not maintained, live animal markets can transmit zoonoses. Because of the openness, newly introduced animals may come in direct contact with sales clerks, butchers, and customers or to other animals which they would never interact with in the wild. This may allow for some animals to act as intermediate hosts, helping a disease spread to humans.[27]

Due to unhygienic sanitation standards and the connection to the spread of zoonoses and pandemics, critics have grouped live animal markets together with factory farming as major health hazards in China and across the world.[28][29][30][31] In March and April 2020, some reports have said that wildlife markets in Asia,[32][33][34] Africa,[35][36][37] and in general all over the world are prone to health risks.[38]

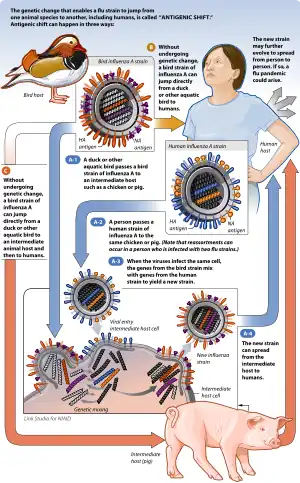

Avian influenza

H5N1 avian flu outbreaks can be traced to live animal markets where the potential for zoonotic transmission is greatly increased.[27][39][40]

COVID-19

The exact origin of the COVID-19 pandemic is yet to be confirmed as of February 2021[41] and was originally linked to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, China due to reports that two-thirds of the initial cases had direct exposure to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan.[42][43][44][45] although a 2021 WHO investigation concluded that the Huanan market was unlikely to be the origin due to the existence of earlier cases.[41] The Huanan market sold "live wolf pups, salamanders, civets, and bamboo rats" amongst other species.[46]

Alternate theories and misinformation emerged in January that the viruses were instead artificially created in a laboratory, but these claims were largely rejected by scientists and news outlets as unfounded rumours and conspiracy theories.[47][48][49][50] In April 2020, United States intelligence officials launched examinations into unverified reports that the virus may have originated from accidental exposure of scientists studying coronaviruses in bats at the BSL-4-capable Wuhan Institute of Virology rather than a wildlife market.[51][52][53][47] On 3 May 2020, United States Secretary of State Mike Pompeo claimed that there is "enormous evidence" that the coronavirus outbreak originated in a Chinese laboratory.[54] However, Pompeo later distanced himself from the claim,[55] while virologists have stated that available data overwhelmingly suggest that there was no chance of scientific misconduct or negligence such that the virus emerged from a lab.[56][57][58]

In May 2020, George Gao, the director of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, said animal samples collected from the seafood market had tested negative for the virus, indicating that the market was the site of an early superspreading event, but it was not the site of the initial outbreak.[59] The results of a WHO investigation yielded similar results, confirming what most scientists expected, that the location of the first contact with the virus was still unknown but unlikely to be the Huanan market due to the existence of earlier cases.[41]

Media coverage

During the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Chinese wet markets were heavily criticized in media outlets as a potential source for the virus.[45] Media reports urging for permanent blanket bans on all wet markets, as opposed to solely live animal markets or wildlife markets, have been criticized for undermining infection control needs to be specific about wildlife markets, such as the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market.[60] Media focus on foreign wet markets has also been blamed for distracting public attention from public health threats, such as local sources of zoonotic diseases.[61]

In Western media, wet markets have been portrayed during the COVID-19 pandemic without distinguishing between general wet markets, live animal wet markets, and wildlife markets,[62] using montages of explicit images from different markets across Asia without identifying locations.[60][63][64] Fairness & Accuracy in Reporting criticized several news articles from mainstream media outlets during the first half of 2020 as "ignorant or worse", pointing to sensationalist coverage utilizing graphic images for shock value.[65] These depictions have been criticized as exaggerated and Orientalist, and have been blamed for fueling Sinophobia and "Chinese otherness".[60][63][66][61][64]

Monkeypox

Monkeypox is a viral zoonotic double stranded DNA disease that occurs in both humans and animals. It often accumulates in wild animals and is transmitted by close contact within animal trade.[67] It is most commonly found in central and west Africa where it is carried in a number of infected species including monkeys, apes, rats, prairie dogs, and other small rodents.[68] In an attempt to reduce the rate of disease spread, researchers believe minimizing direct and indirect contact rates between species in wildlife trade markets is the most practical solution.[69]

SARS

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), often referred to as a severe form of pneumonia, is a highly contagious zoonotic respiratory illness causing extreme breathing difficulties. Factors attributing to widespread dispersal include the destruction of wildlife natural ecosystems, overextended urbanization effects on biodiversity, and contact with bacterially contaminated objects.[70] The 2002–2004 SARS outbreak can be traced to live animal markets where the potential for zoonotic transmission is greatly increased.[27][39][40] In a 2007 study, Chinese scientists identified the presence of SARS-CoV-like viruses in horseshoe bats combined with unsanitary wildlife markets and the culture of eating exotic mammals in southern China as a "time-bomb".[71] In April 2020, scientist Peter Daszak described a Chinese wildlife market as follows: "it is a bit of shock to go to a wildlife market and see this huge diversity of animals live in cages on top of each other with a pile of guts that have been pulled out of an animal and thrown on the floor [...] These are perfect places for viruses to spread."[72]

Chinese environmentalists, researchers and state media have called for stricter regulation of exotic animal trade in the markets.[62] Medical experts Zhong Nanshan, Guan Yi and Yuen Kwok-yung have also called for the closure of wildlife markets since 2010.[73]

Other zoonoses

Ebola virus

Ebola virus disease is a rare infectious disease that is likely transmitted to humans by wild animals. The natural reservoirs of Ebola virus are unknown, but possible reservoirs include fruit bats, non-human primates,[74] rodents, shrews, carnivores, and ungulates.[75]

Transmission of this virus likely occurs when individuals live closely to infected habitats, exchange bodily liquids, or consume infected animals.[76] West Africa's Ebola outbreak was termed the most destructive infectious disease epidemic in recent history, killing a total of 16,000 individuals between 2014 and 2015. Wildlife poachers have the greatest chance of contracting and dispersing this disease at they return from the bush.[77]

HIV

HIV is a life-threatening virus that attacks the immune system. The virus weakens the white blood cell count and their ability to detect and ward off potentially harmful diseases. Dispersal of the disease includes acts of consuming infected bushmeat, pathogens coming into contact with open wounds, and through infected blood transfers.[78] The two major strains of HIV, HIV-1 and HIV-2, are both believed to have originated in West or Central Africa from strains of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), which infects various non-human primate species. Some of these primates affected by SIV are often hunted and trafficked for bushmeat, traditional medicine practices, and for exotic pet trade purposes.

Bubonic plague

Bubonic plague is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis and is transmitted through open wound contact or exposure to contaminated bodily fluids. Oriental rat fleas, which are thought to originate in northern Africa carry the bacteria and transmit the disease by biting and infecting both humans and wild animals.[79]

Marburg virus

Marburg virus, which causes Marburg virus disease, is a zoonotic RNA virus within the filovirus family. It is closely related to the Ebola virus and is transmitted by wild animals to humans. African monkeys and fruit bats are believed to be the main carries of the infectious disease. In 2012 the most recent outbreak occurred in Uganda, where fifteen individuals contracted the disease and four ultimately died from elevated hemorrhagic fevers. Rising numbers of deforestation, urbanization, and exotic animal trade have increased the likeliness of spreading this viral disease.[80]

West Nile virus

West Nile virus is a single stranded RNA virus that can cause neurological diseases within humans. The first outbreak was recorded in Uganda and other areas of West Africa in 1937. Disease transmission is primarily through mosquitos feeding on infected dead birds. The infection then circulates within the mosquito and is transferred to humans or animals when bitten by the infected insect.[81]

African trypanosomiasis

African trypanosomiasis or sleeping sickness is caused by a microscopic parasite called the Trypanosoma brucei, which is transferred to humans and animals through the bite of a tsetse fly.[82] The disease is a reoccurring issue in many rural parts of Africa and over 500,000 individuals currently carry the disease. Livestock, game animals, and wild species of the bush are prone to the infection. Wildlife game markets and other exotic animal trade methods continue to spread transmission. These trade operations have introduced dangerous repercussions as the disease becomes more adaptive to drug resistance.[83]

Prevention and management

Managing the risk of zoonotic diseases includes educating those in the wildlife trade about potential disease hazards. Other ways to manage risk include creating disease surveillance systems to monitor all stages of wildlife trade, from sources to markets. Other suggestions include education about proper storage, handling, and cooking of wildlife.[84][85]

Due to the suspicions that wet markets could have played a role in the emergence of COVID-19, a group of US lawmakers, NIAID director Anthony Fauci, UNEP biodiversity chief Elizabeth Maruma Mrema, and CBCGDF secretary general Zhou Jinfeng called in April 2020 for the global closure of wildlife markets due to the potential for zoonotic diseases and risk to endangered species.[86][87][88][89] In April 2021, the World Health Organization called for a total ban on the sale of live animals in food markets in order to prevent future pandemics.[90]

Disease control intervention

Planetary health studies have called for disease control intervention measures to be implemented at live animal markets in lieu of complete bans.[19][20][21] These include proposals for "standardised global monitoring of water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) conditions", which the World Health Organization announced in April 2020 that it was developing as requirements for wet markets in general to open.[19] Other proposals include less homogeneous policies that are specialized for local social, cultural, and financial factors,[21] as well as new proposed rapid assessment tools for monitoring the hygiene and biosecurity of live animal stalls in markets.[91]

See also

- Global catastrophic risk – Potentially harmful worldwide events

- Globalization and disease – Overview of globalization and disease transmission

- Pandemic prevention – Organization and management of preventive measures against pandemics

- Virgin soil epidemic – Worse effects of disease to populations with no prior exposure

- Wet market – Market selling perishable goods, including meat, produce, and food animals

References

- ↑ Ashley S, Brown S, Ledford J, Martin J, Nash AE, Terry A, Tristan T, Warwick C (2014-10-02). "Morbidity and mortality of invertebrates, amphibians, reptiles, and mammals at a major exotic companion animal wholesaler". Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science. 17 (4): 308–21. doi:10.1080/10888705.2014.918511. PMID 24875063. S2CID 31768738.

- ↑ "Traditional-Medical Knowledge and Perception of Pangolins (Manis sps) among the Awori People, Southwestern Nigeria" (PDF). Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2011.

- ↑ Da Nóbrega Alves, Rômulo Romeu; Da Silva Vieira, Washington Luiz; Santana, Gindomar Gomes (2008). "Reptiles used in traditional folk medicine: conservation implications" (PDF). Biodiversity and Conservation. 17 (8): 2037–2049. doi:10.1007/s10531-007-9305-0. S2CID 42500066.

- ↑ Costa-Neto, Eraldo M. (2005). "Animal-based medicines: biological prospection and the sustainable use of zootherapeutic resources" (PDF). Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 77 (1): 33–43. doi:10.1590/S0001-37652005000100004. ISSN 0001-3765. PMID 15692677.

- ↑ Jugli, Salomi; Chakravorty, Jharna; Meyer-Rochow, Victor Benno (2019-06-15). "Zootherapeutic uses of animals and their parts: an important element of the traditional knowledge of the Tangsa and Wancho of eastern Arunachal Pradesh, North-East India". Environment, Development and Sustainability. 22 (5): 4699–4734. doi:10.1007/s10668-019-00404-6. ISSN 1573-2975.

- ↑ Nijman V (2010-04-01). "An overview of international wildlife trade from Southeast Asia". Biodiversity and Conservation. 19 (4): 1101–1114. doi:10.1007/s10531-009-9758-4. ISSN 1572-9710.

- ↑ Zhang L, Hua N, Sun S (2008-06-01). "Wildlife trade, consumption and conservation awareness in southwest China". Biodiversity and Conservation. 17 (6): 1493–1516. doi:10.1007/s10531-008-9358-8. ISSN 1572-9710. PMC 7088108. PMID 32214694.

- ↑ Alves, Rômulo RN; Alves, Humberto N. (2011-03-07). "The faunal drugstore: Animal-based remedies used in traditional medicines in Latin America". Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 7 (1): 9. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-7-9. ISSN 1746-4269. PMC 3060860. PMID 21385357.

- ↑ Souto, Wedson Medeiros Silva; Barboza, Raynner Rilke Duarte; Fernandes-Ferreira, Hugo; Júnior, Arnaldo José Correia Magalhães; Monteiro, Julio Marcelino; Abi-chacra, Érika de Araújo; Alves, Rômulo Romeu Nóbrega (2018-09-17). "Zootherapeutic uses of wildmeat and associated products in the semiarid region of Brazil: general aspects and challenges for conservation". Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 14 (1): 60. doi:10.1186/s13002-018-0259-y. ISSN 1746-4269. PMC 6142313. PMID 30223856.

- ↑ "Zootherapy: A study from the Northwestern region of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan" (PDF). Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge. 2016. S2CID 54552844. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-02-20.

- ↑ "A COMPARATIVE ASSESSMENT OF ZOOTHERAPEUTIC REMEDIES FROM SELECTED AREAS IN ALBANIA, ITALY, SPAIN AND NEPAL" (PDF). Journal of Ethnobiology. 2010.

- ↑ Rosen GE, Smith KF (August 2010). "Summarizing the evidence on the international trade in illegal wildlife". EcoHealth. 7 (1): 24–32. doi:10.1007/s10393-010-0317-y. PMC 7087942. PMID 20524140.

- ↑ Pfeffer M, Dobler G (April 2010). "Emergence of zoonotic arboviruses by animal trade and migration". Parasites & Vectors. 3 (1): 35. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-3-35. PMC 2868497. PMID 20377873.

- ↑ Tsai P, Scott KA, Gonzalez MC, Pappaioanou M, Keusch GT, et al. (National Research Council (US) Committee on Achieving Sustainable Global Capacity for Surveillance and Response to Emerging Diseases of Zoonotic Origin) (2009). Drivers of Zoonotic Diseases. National Academies Press (US).

- ↑ Greenfield, Patrick (6 April 2020). "Ban wildlife markets to avert pandemics, says UN biodiversity chief". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ↑ Beirne, Piers (May 2021). "Wildlife Trade and COVID-19: Towards a Criminology of Anthropogenic Pathogen Spillover". The British Journal of Criminology. Oxford University Press. 61 (3): 607–626. doi:10.1093/bjc/azaa084. ISSN 1464-3529. PMC 7953978. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

Wildlife trade, both legal and illegal and in all jurisdictions, must be abolished. All this must be done with due respect for differently resourced low- and middle-income countries and for the needs of those indigenes who through physical need and customary tradition engage in (non-commodified) subsistence hunting.

- ↑ Bonyhady, Nick (4 April 2020). "Canberra to push China to ban wildlife meat trade". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ↑ Ceballos, Gerardo; Ehrlich, Paul R.; Raven, Peter H. (June 1, 2020). "Vertebrates on the brink as indicators of biological annihilation and the sixth mass extinction". PNAS. 117 (24): 13596–13602. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11713596C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1922686117. PMC 7306750. PMID 32482862.

The horrific coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) pandemic that we are experiencing, of which we still do not fully understand the likely economic, political, and social global impacts, is linked to wildlife trade. It is imperative that wildlife trade for human consumption is considered a gigantic threat to both human health and wildlife conservation. Therefore, it has to be completely banned, and the ban strictly enforced, especially in China, Vietnam, Indonesia, and other countries in Asia

- 1 2 3 Nadimpalli, Maya L; Pickering, Amy J (2020). "A call for global monitoring of WASH in wet markets". The Lancet Planetary Health. 4 (10): e439–e440. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30204-7. ISSN 2542-5196. PMC 7541042. PMID 33038315.

- 1 2 Petrikova, Ivica; Cole, Jennifer; Farlow, Andrew (2020). "COVID-19, wet markets, and planetary health". The Lancet Planetary Health. 4 (6): e213–e214. doi:10.1016/s2542-5196(20)30122-4. ISSN 2542-5196. PMC 7832206. PMID 32559435.

- 1 2 3 Barnett, Tony; Fournié, Guillaume (January 2021). "Zoonoses and wet markets: beyond technical interventions". The Lancet Planetary Health. 5 (1): e2–e3. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30294-1. ISSN 2542-5196. PMC 7789916. PMID 33421407.

- ↑ May C. "Transmission Routes of Zoonotic Diseases" (PDF).

- ↑ Lindahl JF, Grace D (2015-11-27). "The consequences of human actions on risks for infectious diseases: a review". Infection Ecology & Epidemiology. 5: 30048. doi:10.3402/iee.v5.30048. PMC 4663196. PMID 26615822.

- 1 2 Salyer SJ, Silver R, Simone K, Barton Behravesh C (December 2017). "Prioritizing Zoonoses for Global Health Capacity Building-Themes from One Health Zoonotic Disease Workshops in 7 Countries, 2014-2016". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 23 (13): S55–S64. doi:10.3201/eid2313.170418. PMC 5711306. PMID 29155664.

- 1 2 3 Aguirre AA (December 2017). "Changing Patterns of Emerging Zoonotic Diseases in Wildlife, Domestic Animals, and Humans Linked to Biodiversity Loss and Globalization". ILAR Journal. 58 (3): 315–318. doi:10.1093/ilar/ilx035. PMID 29253148.

- 1 2 Kurpiers, Laura A.; Schulte-Herbrüggen, Björn; Ejotre, Imran; Reeder, DeeAnn M. (2016). "Bushmeat and Emerging Infectious Diseases: Lessons from Africa". In Angelici, Francesco M. (ed.). Problematic Wildlife. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 507–551. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-22246-2_24. ISBN 978-3-319-22245-5. PMC 7123567.

- 1 2 3 Greenfield, Patrick (2020-04-06). "Ban wildlife markets to avert pandemics, says UN biodiversity chief". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 2020-04-10.

- ↑ "China's Wet Markets, America's Factory Farming". National Review. 2020-04-09. Archived from the original on 9 April 2020. Retrieved 2020-04-10.

- ↑ "Building a factory farmed future, one pandemic at a time". grain.org. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 2020-04-10.

- ↑ info@sustainablefoodtrust.org, Sustainable Food Trust-. "Sustainable Food Trust". Sustainable Food Trust. Archived from the original on 21 April 2020. Retrieved 2020-04-10.

- ↑ Fickling, David (3 April 2020). "China Is Reopening Its Wet Markets. That's Good". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 9 April 2020.

- ↑ "China Could End the Global Trade in Wildlife". Sierra Club. 2020-03-26. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 2020-03-30.

- ↑ "Coronavirus expert calls for shut down of Asia's wildlife markets". Nine News Australia. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 2020-03-30.

- ↑ "Wild Animal Markets Spark Fear in Fight Against Coronavirus". Time. Archived from the original on 27 March 2020. Retrieved 2020-04-15.

- ↑ "Africa Risks Virus Outbreak From Wildlife Trade". WildAid. 2020-02-28. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 2020-03-30.

- ↑ "A sea change in China's attitude towards wildlife exploitation may just save the planet". Daily Maverick. 2020-03-02. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

Knights hoped China would also play a role to help "countries around the world. It's no good simply banning the trade in China. The same risks are very much out there in Asia as well as Africa."

- ↑ "Crackdown on wet markets and illegal wildlife trade could prevent the next pandemic". Mongabay India. 2020-03-25. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

...what we do know is that wet markets such as Wuhan, and for that matter Agartala's Golbazar or the thousands such that exist in Asia and Africa allow for easy transmission of viruses and other pathogens from animals to humans.

- ↑ Mekelburg, Madlin. "Fact-check: Is Chinese culture to blame for the coronavirus?". Austin American-Statesman. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 2020-03-30.

- 1 2 "New Coronavirus 'Won't Be the Last' Outbreak to Move from Animal to Human". Goats and Soda. NPR. 2020-02-05. Archived from the original on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 2020-02-29.

- 1 2 "Calls for global ban on wild animal markets amid coronavirus outbreak". The Guardian. London. 2020-01-24. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 2020-02-29.

- 1 2 3 Fujiyama, Emily Wang; Moritsugu, Ken (11 February 2021). "EXPLAINER: What the WHO coronavirus experts learned in Wuhan". Associated Press. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ↑ Hui, David S.; I Azhar, Esam; Madani, Tariq A.; Ntoumi, Francine; Kock, Richard; Dar, Osman; Ippolito, Giuseppe; Mchugh, Timothy D.; Memish, Ziad A.; Drosten, Christian; Zumla, Alimuddin; Petersen, Eskild (2020). "The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health – The latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. Elsevier BV. 91: 264–266. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009. ISSN 1201-9712. PMC 7128332. PMID 31953166.

- ↑ Huang, Chaolin; Wang, Yeming; Li, Xingwang; Ren, Lili; Zhao, Jianping; Hu, Yi; Zhang, Li; Fan, Guohui; Xu, Jiuyang; Gu, Xiaoying; Cheng, Zhenshun (24 January 2020). "Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China". The Lancet. 395 (10223): 497–506. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7159299. PMID 31986264.

- ↑ Keevil, William; Lang, Trudie; Hunter, Paul; Solomon, Tom (24 January 2020). "Expert reaction to first clinical data from initial cases of new coronavirus in China". Science Media Centre. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- 1 2 Spinney, Laura (2020-03-28). "Is factory farming to blame for coronavirus?". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 2020-03-30.

Most of the attention so far has been focused on the interface between humans and the intermediate host, with fingers of blame being pointed at Chinese wet markets and eating habits,...

- ↑ "Wet markets are not wildlife markets, so stop calling for their ban". Quartz Media, Inc. Uzabase. 16 April 2020.

- 1 2 Rapoze, Kenneth (14 April 2020). "China Lab In Focus Of Coronavirus Outbreak". Forbes. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

For months, anyone who said the new SARS coronavirus might have come out of a virology research lab in Wuhan, China was dismissed as a right wing xenophobe [...] But on Tuesday, the narrative flipped. It's no longer a story shared by China bears and President Trump fans. Today, Josh Rogin, who is said to be as plugged into the State Department as any Washington Post columnist, was shown documents dating back to 2015 revealing how the U.S. government was worried about safety standards at that Wuhan lab. [...] Rogin's reporting suggests that government officials were well aware of the research being conducted in the lab on bat coronaviruses and were worried that the lab still had sub-par safety standards.

- ↑ Josh Taylor (31 January 2020). "Bat soup, dodgy cures and 'diseasology': the spread of coronavirus misinformation". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ↑ Kate Gibson (3 February 2020). "Twitter bans Zero Hedge after it posts coronavirus conspiracy theory". CBS News. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ↑ Shield, Charli (16 April 2020). "Coronavirus Pandemic Linked to Destruction of Wildlife and World's Ecosystems". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

After the novel coronavirus broke out in Wuhan, China in late December 2019, it didn't take long for conspiracy theorists to claim it was manufactured in a nearby lab. Scientific consensus, on the other hand, is that the virus — SARS-CoV-2 — is a zoonotic disease that jumped from animal to human. It most likely originated in a bat, possibly before passing through another mammal.

- ↑ Rincon, Paul (16 April 2020). "Coronavirus: Is there any evidence for lab release theory?". BBC. Archived from the original on 16 April 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ↑ Lipton, Eric; Sanger, David E.; Haberman, Maggie; Shear, Michael D.; Mazzetti, Mark; Barnes, Julian E. (11 April 2020). "He Could Have Seen What Was Coming: Behind Trump's Failure on the Virus". New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 April 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ↑ Dilanian, Ken; Kube, Courtney (16 April 2020). "U.S. intel community examining whether coronavirus emerged accidentally from a Chinese lab". NBC News. Archived from the original on 16 April 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

The U.S. intelligence community is examining whether the coronavirus that caused the global pandemic emerged accidentally from a Chinese research lab studying diseases in bats [...] Separately, the idea that the virus emerged at an animal market in Wuhan continues to be debated by experts. Dr. Ronald Waldman, a former official at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and a public health expert at George Washington University, said the theory has fallen out of favor in some quarters, in part because one of the early infected persons had no connection to the market.

- ↑ Borger, Julian (2020-05-03). "Mike Pompeo: 'enormous evidence' coronavirus came from Chinese lab". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 4 May 2020. Retrieved 2020-05-04.

- ↑ Hansler, Jennifer; Cole, Devan (17 May 2020). "Pompeo backs away from theory he and Trump were pushing that coronavirus originated in Wuhan lab". CNN. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ↑ Staff, Science News (4 May 2020). "Pressure grows on China for independent investigation into pandemic's origins". Science | AAAS. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ↑ Graham, Rachel L.; Baric, Ralph S. (May 2020). "SARS-CoV-2: Combating Coronavirus Emergence". Immunity. 52 (5): 734–736. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2020.04.016. PMC 7207110. PMID 32392464.

- ↑ Brumfiel, Geoff; Kwong, Emily (23 April 2020). "Virus Researchers Cast Doubt On Theory Of Coronavirus Lab Accident". Archived from the original on 28 April 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ↑ Areddy, James T. (26 May 2020). "China Rules Out Animal Market and Lab as Coronavirus Origin". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- 1 2 3 Lynteris, Christos; Fearnley, Lyle (2 March 2020). "Why shutting down Chinese 'wet markets' could be a terrible mistake". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- 1 2 Boyle, Louise (15 May 2020). "Wet markets are not the problem – focus on the billion-dollar international trade in wild animals, experts say". The Independent. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- 1 2 "Wuhan Is Returning to Life. So Are Its Disputed Wet Markets". Bloomberg Australia-NZ. 8 April 2020. Archived from the original on 9 April 2020.

- 1 2 Samuel, Sigal (15 April 2020). "The coronavirus likely came from China's wet markets. They're reopening anyway". Vox. Archived from the original on 16 April 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- 1 2 St. Cavendish, Christopher (11 March 2020). "No, China's fresh food markets did not cause coronavirus". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ↑ Cho, Joshua (8 May 2020). "Mainstream media's racist trope: Blaming COVID-19 on China's "wet markets"". Salon. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ↑ Palmer, James (27 January 2020). "Don't Blame Bat Soup for the Coronavirus". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ↑ "Monkeypox". www.who.int. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- ↑ "Monkeypox" (PDF). The Center for Food Security & Public Health. Iowa State University.

- ↑ Karesh WB, Cook RA, Bennett EL, Newcomb J (July 2005). "Wildlife trade and global disease emergence". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (7): 1000–2. doi:10.3201/eid1107.050194. PMC 3371803. PMID 16022772.

- ↑ "WHO | SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome)". WHO. Retrieved 2019-04-18.

- ↑ Cheng, VC (2007). "Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus as an Agent of Emerging and Reemerging Infection". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 20 (4): 660–94. doi:10.1128/CMR.00023-07. PMC 2176051. PMID 17934078.

- ↑ "How did coronavirus break out? Theories abound as researchers race to solve genetic detective story". Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ↑ "Wuhan coronavirus another reason to ban China's wildlife trade forever". South China Morning Post. 2020-01-29. Retrieved 2020-04-04.

- ↑ "What is Ebola Virus Disease?". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 5 November 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ↑ Olivero, Jesús; Fa, John E.; Real, Raimundo; Farfán, Miguel Ángel; Márquez, Ana Luz; Vargas, J. Mario; Gonzalez, J. Paul; Cunningham, Andrew A.; Nasi, Robert (2017). "Mammalian biogeography and the Ebola virus in Africa" (PDF). Mammal Review. 47: 24–37. doi:10.1111/mam.12074.

We found published evidence from cases of serological and/or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) positivity of EVD in non- human mammal, or of EVD-linked mortality, in 28 mammal species: 10 primates, three rodents, one shrew, eight bats, one carnivore, and five ungulates

- ↑ "Ebola virus disease". www.who.int. Retrieved 2019-04-18.

- ↑ Egbetade AO, Sonibare AO, Meseko CA, Jayeola OA, Otesile EB (2015-10-11). "Implications of Ebola virus disease on wildlife conservation in Nigeria". The Pan African Medical Journal. 22 (Suppl 1): 16. doi:10.11604/pamj.supp.2015.22.1.6617. PMC 4695512. PMID 26740844.

- ↑ "What is HIV? - HIV/AIDS". www.hiv.va.gov. Retrieved 2019-04-18.

- ↑ "History of the Plague | Plague | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2018-11-27. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- ↑ "Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever (Marburg HF) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2019-02-25. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- ↑ Colpitts TM, Conway MJ, Montgomery RR, Fikrig E (October 2012). "West Nile Virus: biology, transmission, and human infection". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 25 (4): 635–48. doi:10.1128/CMR.00045-12. PMC 3485754. PMID 23034323.

- ↑ "CAB Direct". www.cabdirect.org. Retrieved 2019-05-05.

- ↑ Simarro PP, Cecchi G, Paone M, Franco JR, Diarra A, Ruiz JA, Fèvre EM, Courtin F, Mattioli RC, Jannin JG (November 2010). "The Atlas of human African trypanosomiasis: a contribution to global mapping of neglected tropical diseases". International Journal of Health Geographics. 9 (1): 57. doi:10.1186/1476-072X-9-57. PMC 2988709. PMID 21040555.

- ↑ Lee, Tien Ming; Sigouin, Amanda; Pinedo-Vasquez, Miguel; Nasi, Robert (2020). "The Harvest of Tropical Wildlife for Bushmeat and Traditional Medicine". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 45: 145–170. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-102016-060827.

- ↑ Shiferaw, Miriam L.; Doty, Jeffrey B.; Maghlakelidze, Giorgi; Morgan, Juliette; Khmaladze, Ekaterine; Parkadze, Otar; Donduashvili, Marina; Wemakoy, Emile Okitolonda; Muyembe, Jean-Jacques; Mulumba, Leopold; Malekani, Jean; Kabamba, Joelle; Kanter, Theresa; Boulanger, Linda Lucy; Haile, Abraham; Bekele, Abyot; Bekele, Meseret; Tafese, Kasahun; McCollum, Andrea A.; Reynolds, Mary G. (2017). "Frameworks for Preventing, Detecting, and Controlling Zoonotic Diseases". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 23 (13): S71-6. doi:10.3201/eid2313.170601. PMC 5711328. PMID 29155663.

- ↑ Forgey, Quint (3 April 2020). "'Shut down those things right away': Calls to close 'wet markets' ramp up pressure on China". Politico. Archived from the original on 4 April 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ↑ Greenfield, Patrick (April 6, 2020). "Ban wildlife markets to avert pandemics, says UN biodiversity chief". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ↑ Fortier-Bensen, Tony (9 April 2020). "Sen. Lindsey Graham, among others, urge global ban of live wildlife markets and trade". ABC News. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ↑ Beech, Peter (18 April 2020). "What we've got wrong about China's 'wet markets' and their link to COVID-19". World Economic Forum. Archived from the original on 18 April 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ↑ Forrest, Adam (13 April 2021). "WHO calls for ban on sale of live animals in food markets to combat pandemics". The Independent. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ↑ Soon, Jan Mei; Abdul Wahab, Ikarastika Rahayu (2021-09-01). "On-site hygiene and biosecurity assessment: A new tool to assess live bird stalls in wet markets". Food Control. 127: 108108. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2021.108108. ISSN 0956-7135.